Key Points

Anchoring IgG-degrading enzymes to platelets cleaves and neutralizes pathogenic antiplatelet antibodies without collateral IgG damage.

Platelets with surface-bound IgG-degrading enzymes are protected from clearance in murine models of ITP.

Abstract

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an acquired bleeding disorder characterized by immunoglobulin G (IgG)–mediated platelet destruction. Current therapies primarily focus on reducing antiplatelet antibodies using immunosuppression or increasing platelet production with thrombopoietin mimetics. However, there are no universally safe and effective treatments for patients presenting with severe life-threatening bleeding. The IgG-degrading enzyme of Streptococcus pyogenes (IdeS), a protease with strict specificity for IgG, prevents IgG-driven immune disorders in murine models, including ITP. In clinical trials, IdeS prevented IgG-mediated kidney transplant rejection; however, the concentration of IdeS used to remove pathogenic antibodies causes profound hypogammaglobulinemia, and IdeS is immunogenic, which limits its use. Therefore, this study sought to determine whether targeting IdeS to FcγRIIA, a low-affinity IgG receptor on the surface of platelets, neutrophils, and monocytes, would be a viable strategy to decrease the pathogenesis of antiplatelet IgG and reduce treatment-related complications of nontargeted IdeS. We generated a recombinant protein conjugate by site-specifically linking the C-terminus of a single-chain variable fragment from an FcγRIIA antibody, clone IV.3, to the N-terminus of IdeS (scIV.3-IdeS). Platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS had reduced binding of antiplatelet IgG from patients with ITP and decreased platelet phagocytosis in vitro, with no decrease in normal IgG. Treatment of mice expressing human FcγRIIA with scIV.3-IdeS reduced thrombocytopenia in a model of ITP and significantly improved the half-life of transfused platelets expressing human FcγRIIA. Together, these data suggest that scIV.3-IdeS can selectively remove pathogenic antiplatelet IgG and may be a potential treatment for patients with ITP and severe bleeding.

Introduction

Severe bleeding is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). Although advances such as thrombopoietin mimetics have improved the quality of life for patients with ITP, there is no universally safe and effective treatment for patients presenting with severe life-threatening bleeding. Severe bleeding is estimated to occur in up to 20% of children and 10% of adults with ITP. Moreover, ∼1% of patients with ITP present with intracranial hemorrhage, arguably the most devastating complication of ITP.1 Life-threatening bleeding is also a significant complication for patients with alloimmune thrombocytopenia, including those with neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia and patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation or cancer treatment who develop alloantibodies.2,3 Random-donor platelet transfusions are often given in these situations, but the clinical utility is limited because the platelets are rapidly cleared by circulating immunoglobulin G (IgG). Immunomodulating agents such as steroids and IV immunoglobulin as well as thrombopoietin mimetics lack the rapid onset of action needed in these contexts. Clearly, there is a critical need for novel approaches to treat severe bleeding in the setting of ITP.

The recombinant IgG-degrading enzyme of Streptococcus pyogenes (IdeS) is such a therapy that could be used for treating severe bleeding in the setting of IgG-driven diseases such as ITP. IdeS is a cysteine protease secreted by S pyogenes that facilitates evasion of the immune response by cleaving the heavy chain of IgG, generating an F(ab′)2 and 2 Fc fragments.4 Because IdeS can selectively and rapidly neutralize the Fc-mediated effector function of human IgG, it has been developed into a treatment for IgG-mediated disorders. In murine models, IdeS ameliorates a range of IgG-driven disorders, including ITP and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).5,6

Although effective in clinical trials, IdeS has limitations to its use. First, IdeS dose-dependently removes >95% of IgG from circulation, and it can take >3 weeks for IgG to return to pretreatment levels.7 The global removal of IgG places the patient at risk for severe infection. Second, for patients with anti–glomerular basement membrane antibodies, the pathogenic IgG can return to toxic levels after IdeS treatment, and ∼50% of patients have to resume their previous treatment.8 However, subsequent doses of IdeS are not recommended because of concern that anti-IdeS antibodies could trigger a hypersensitivity reaction.8 Interestingly, in humans, the global clearance of IgG and IdeS immunogenicity occur at higher (>100 nM) but not lower (<25 nM) plasma concentrations of IdeS.7

Targeting IdeS to the surface of platelets to neutralize antiplatelet IgG before platelet transfusion is a potential strategy to obtain a rapid and sustained rise in platelet count in patients with ITP while minimizing IdeS adverse effects. Therefore, in this study, FcγRIIA, a low-affinity IgG receptor, was chosen as the binding target for IdeS based on the following properties: (1) selective expression on platelets, monocytes, and neutrophils9 ; (2) proximity to 2 of the most common antibody targets in patients with ITP, αIIbβ3 and GPIb/V/IX10 ; (3) minimal importance in hemostasis11 ; and (4) involvement in antibody-mediated platelet activation.12 Moreover, a well-characterized, high-affinity, function-blocking humanized monoclonal antibody specific for FcγRIIA designated IV.3 is available.13-15 Using a site-specific bioconjugation strategy, we conjugated the C-terminus of a single-chain variable fragment of IV.3 (scIV.3) to the N-terminus of IdeS, producing a single protein (scIV.3-IdeS) capable of anchoring IdeS to the surface of FcγRIIA-expressing cells. Remarkably, platelets decorated with scIV.3-IdeS cleaved platelet-bound IgG, resulting in a decrease in platelet phagocytosis in vitro, without inducing proteolytic cleavage of nonpathogenic IgG. Furthermore, scIV.3-IdeS was capable of rapidly ameliorating thrombocytopenia in a mouse model of ITP. These data suggest that scIV.3-IdeS alone or in conjunction with other therapies could provide a novel treatment for patients with immune platelet disorders and severe bleeding. Moreover, cell-specific targeting of IdeS could reduce the disease severity of other IgG-driven disorders with potentially less immune suppression than current therapies.

Methods

Isolation of PRP and platelets

Research involving humans was approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) Institutional Review Board. Blood was collected into vacutainers containing sodium citrate and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 200g to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Where indicated, citrated PRP was supplemented with 1 mM of CaCl2 and used without adjustment of platelet count. To isolate platelets from PRP, acid citrate dextrose and prostaglandin E1 were added, and the samples were then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 2000g. The pelleted platelets were resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer and adjusted to 3.0 × 108 platelets/mL, unless otherwise stated.

All studies involving mice were approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Blood was drawn from the inferior vena cava of mice into sodium citrate. Blood was diluted with equal volumes of Tyrode’s buffer and isolated in the same manner as human platelets.

Expression, sortase modification, and purification of IV.3 scFv-LPETGG and GGG-IdeS

VH and VL sequences for IV.3 were fused with a (GGGGS)3 linker and purchased as a gene block. This sequence was cloned into previously reported bacterial plasmid pBAD/scFv-LPETGG.16,17 scIV.3-LPETGG was expressed in bacteria and purified using anti-FLAG resin. scIV.3-LPETGG was modified with an FAM peptide as previously described.16 Similarly, a complementary DNA encoding amino acids 30 to 339 of IdeS (NBCI WP_010922160), corresponding to the mature proteolytic enzyme,4 was cloned into the N-terminal sortag vector, pRSET/GGG. GGG-IdeS was expressed in bacteria and purified using Ni-NTA agarose. The purity of both proteins was confirmed to be >95% by size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography. The proteins were reacted with sortase-A5 at a ratio of 1:1.5 (scIV.3-LPETGG/GGG-IdeS), and the desired protein product, scIV.3-IdeS, was purified by size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography.

Characterization of recombinant protein binding by flow cytometry

Washed platelets (7.5 × 106), blood (5 μL), or THP-1 cells (5 × 105) were incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-FAM and analyzed by flow cytometry. Blood samples were simultaneously stained with scIV.3-FAM and cell-specific antibodies against monocytes (CD14; phycoerythrin [PE]–Cy7 conjugated), neutrophils (CD66b; PerCP-CY5 conjugated), and platelets (CD42a; PE conjugated). To characterize the binding of scIV.3-IdeS, increasing concentrations of His-tagged proteins were incubated with platelets (7.5 × 106), followed by the addition of an Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-His Tag antibody. Where indicated, 30 nM of commercial IV.3 (cIV.3; StemCell Technologies) was added to platelets 15 minutes before the addition of scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS.

Aggregation

Aggregation was measured under stirring conditions (1000 rpm) at 37°C. Platelets were stimulated with collagen, adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP), mouse monoclonal anti-human CD9 antibody (clone ALB6), or rabbit monoclonal anti-human CD9 antibody (Abcam) at indicated concentrations. Where appropriate, samples were treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS for 15 minutes before being stimulated.

IgG degradation

Human IgG was resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer to 2 mg/mL and incubated with predetermined concentrations of recombinant proteins for 1 hour at 37°C. Reactions were stopped with 5X Laemmli sample buffer and separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. Gels were stained with Coomassie dye and scanned on a Li-COR Odyssey CLX imager.

Platelet spreading

Eight-well chambered slides were coated with fibrinogen (100 μg/mL), and platelets (2 × 106 platelets per mL) were then allowed to spread for 1 hour at 37°C. Adherent platelets were stained with a recombinant protein and Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated CD41 for 30 minutes and fixed. Where indicated, cIV.3 (30 nM) was added to platelets before the addition of recombinant protein. Images were obtained on a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope using a 60×/1.40 oil objective.

In vitro antiplatelet antibody cleavage

Washed platelets (7.5 × 106) were coincubated with recombinant protein (scIV.3, IdeS, or scIV.3-IdeS) and rabbit anti-human CD41 or CD42b antibodies (250 ng), polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse platelet serum (RAMS), or sera from patients with ITP (1:25 dilution) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Afterward, a CoraLite 594–conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody specific to the heavy chain of rabbit IgG or an APC-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody specific to the Fc fragment of human IgG was incubated with the platelets for 30 minutes. Samples were then fixed and analyzed by flow cytometry. As a control, increasing concentrations of platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS were incubated with equal volumes of autologous platelet-poor plasma for 1 hour at 37°C, and a western blot to detect human IgG was performed to measure IgG cleavage.

In vitro phagocytosis

THP-1 cells (1 × 106 cells) were differentiated overnight in a 24-well plate by the addition of 2 ng/mL of transforming growth factor-β1 and 50 nM of 1,25-(OH)2-vitamin D3 to cell culture media (RPMI 1640, 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM of L-glutamine, 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin). The next day, THP-1 cells were activated by 15 ng/mL of PMA for 30 minutes, and the media was then replaced. Concurrently with THP-1 cell preparation, platelets were stained with 5 μM of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl-ester (CFSE) and then incubated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS and commercial antiplatelet antibodies (rabbit anti-CD41 and anti-CD42b antibodies; 250 ng) or ITP sera (1:25 dilution). Antibody-treated platelets (1 × 107) were washed and then incubated with THP-1 cells for 60 minutes at 37°C. Wells were washed with PBS, and THP-1 cells were then detached with trypsin. Cells were stained with anti-CD42a antibodies to detect platelets adhered to the THP-1 cells but not internalized. Cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde, and the samples were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Mouse model of antibody-mediated platelet refractoriness

Platelets were collected from mice deficient in murine FcγRα receptors and expressing the full complement of human FcγR (hFcγR) receptors (hFcγRItgIIAtgIIBtgIIIAtgIIIBtgmFcγRnull mice; a gift from Jeffrey V. Ravetch).9 Washed platelets were incubated with 5 μM of CFSE for 15 minutes at 37°C. Platelets were washed and then treated with either control or scIV.3-IdeS (20 nM) for 15 minutes. CFSE-stained platelets (1.5 × 108 platelets in 200 μL) were tail vein injected into wild-type C57BL/6J mice that were intraperitoneally injected with RAMS (25 μL) ∼20 hours before platelet transfusion. Blood was collected via tail bleed at 1 and 4 hours posttransfusion. Blood (5 μL) was stained with an anti-CD41 antibody (MWReg30; Alexa Fluo 647), and total platelets (CD41+) and transfused platelets (CFSE+/CD41+) were enumerated using a Cytek Aurora flow cytometer.

Passive models of ITP in mice

Mice deficient in murine FcγRα receptors and expressing the full complement of hFcγR receptors (hFcγRItgIIAtgIIBtgIIIAtgIIIBtgmFcγRnull mice; a gift from Jeffrey V. Ravetch) were IV injected with scIV.3-IDeS (10 μg) or Tyrode’s buffer.9 After 30 minutes, a retroorbital bleed was performed, and mice were then intraperitoneally injected with RAMS. Blood was drawn via retroorbital bleed at 2 and 24 hours after antibody injection. A Hemavet 950FS was used to count platelets. Blood was stained with anti-CD42a and anti-His Tag antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Platelet factor 4–dependent P-selectin expression assay

Platelets (6 × 106) were incubated with platelet factor 4 (37.5 μg/mL) and either scIV.3-IdeS or Tyrode’s buffer for 30 minutes. Serum (10 μL) from patients with HIT was then mixed into each sample and incubated without agitation at room temperature. After 1 hour, platelets were stained with APC-conjugated anti-CD41 and fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti–P-selectin antibodies, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry. As a positive control, platelets were stimulated with PAR1-activating peptide (NH2-SFLLRN; 25 μM).

Data analysis and statistics

GraphPad Prism 7 software was used to analyze data and calculate statistical significance. The statistical test used to analyze each set of data is specified in the figure legend.

Results

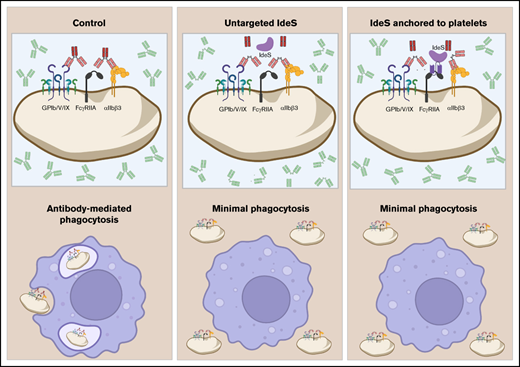

Characterization of the binding properties of scIV.3

Fluorescently labeled scIV.3 was incubated with platelets from wild-type mice, which lack FcγRIIA, or transgenic mice expressing hFcγRIIA to determine whether scIV.3 was specific for hFcγRIIA. As shown in Figure 1, scIV.3-FAM bound to platelets expressing hFcγRIIA in a concentration-dependent manner (Kd, 0.27 nM). In contrast, there was no detectable binding of scIV.3-FAM to platelets from FcγRIIA-null mice (Figure 1A). To determine the affinity with which scIV.3 binds to human cells expressing FcγRIIA, increasing concentrations of scIV.3-FAM were incubated with THP-1 cells (a monocyte-like cell line) or platelets. The FAM-conjugated scIV.3 bound to both THP-1 cells and platelets with a high affinity, at Kd of 11 and 1 nM, respectively (Figure 1B). Because of the ∼100-fold difference in FcγRIIA expression between THP-1 (171 000 ± 13 000 copies per cell) and platelets (1000-5000 copies per platelet), data are presented as percentage bound relative to highest concentration tested per cell type.12,18,19 To determine whether scIV.3 and cIV.3 had overlapping binding sites, platelets were treated with cIV.3 before staining with scIV.3-FAM. As expected, incubation of platelets with cIV.3 prevented scIV.3-FAM from binding, as analyzed by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry (Figure 1C-D).

Characterization of the binding properties of scIV.3. (A) Increasing concentrations of FAM-conjugated scIV.3 (scIV.3-FAM) were incubated with platelets from wild-type mice (hFcγRIInull) or hFcγRIIA transgenic mice (hFcγRIIATGN), and the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 3 independent experiments was reported. (B) Representative histograms of THP-1 cells stained with select concentrations of scIV.3-FAM. THP-1 cells (green dashed line) or human platelets (black line) were incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-FAM, and data are reported as percentage of maximum MFI for each cell type (n = 3-4). (C) Representative microscopic images (60× objective) of human platelets (CD41+) spread on fibrinogen, treated with control or cIV.3 (30 nM), and then stained with scIV.3-FAM (5 nM). (D) Flow cytometry was used to quantify the binding of scIV.3-FAM to human platelets after incubation with or without cIV.3 (data represent n = 4; mean ± standard deviation [SD]). (E) Human whole blood was incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-FAM and normalized to cIV.3 (30 nM). (F) Human platelets were treated with scIV.3 (50 nM) or control and then stimulated with mouse anti-human CD9 antibodies, an FcγRIIA-specific agonist (data represent n = 5; mean ± SD). Two-way statistical analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction was performed. Kd, distribution coefficient. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Characterization of the binding properties of scIV.3. (A) Increasing concentrations of FAM-conjugated scIV.3 (scIV.3-FAM) were incubated with platelets from wild-type mice (hFcγRIInull) or hFcγRIIA transgenic mice (hFcγRIIATGN), and the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 3 independent experiments was reported. (B) Representative histograms of THP-1 cells stained with select concentrations of scIV.3-FAM. THP-1 cells (green dashed line) or human platelets (black line) were incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-FAM, and data are reported as percentage of maximum MFI for each cell type (n = 3-4). (C) Representative microscopic images (60× objective) of human platelets (CD41+) spread on fibrinogen, treated with control or cIV.3 (30 nM), and then stained with scIV.3-FAM (5 nM). (D) Flow cytometry was used to quantify the binding of scIV.3-FAM to human platelets after incubation with or without cIV.3 (data represent n = 4; mean ± standard deviation [SD]). (E) Human whole blood was incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-FAM and normalized to cIV.3 (30 nM). (F) Human platelets were treated with scIV.3 (50 nM) or control and then stimulated with mouse anti-human CD9 antibodies, an FcγRIIA-specific agonist (data represent n = 5; mean ± SD). Two-way statistical analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction was performed. Kd, distribution coefficient. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Because neutrophils, monocytes, and platelets express FcγRIIA, it was important to next determine the cellular distribution of scIV.3-FAM in these populations in blood. To do this, human blood was incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-FAM or cIV.3.9 scIV.3-FAM bound similarly to neutrophils, monocytes, and platelets in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1E). To assess whether the binding of scIV.3 was functionally relevant, we examined the ability of scIV.3 to block platelet aggregation mediated by anti-CD9 antibodies, a known Fcγ RIIA-dependent agonist.20-22 Tyrode’s buffer (control)–treated platelets exhibited dose-dependent aggregation in response to stimulation with anti-CD9 antibodies. In contrast, platelets pretreated with scIV.3 (50 nM) had a >90% reduction in aggregation, even at the highest concentration of anti-CD9 antibody tested (5 μg/mL; Figure 1F). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that scIV.3 retains the binding specificity and affinity for FcγRIIA.

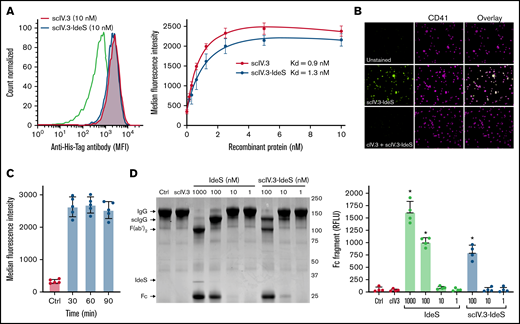

Generation and characterization of recombinant scIV.3-IdeS

To determine whether the conjugation of IdeS to the C-terminus of scIV.3 affected its affinity for FcγRIIA, we incubated increasing concentrations of His-tagged scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS with human platelets (Figure 2A). The scIV.3-IdeS fusion protein was found to have similar binding affinity (Kd, 1.3 nM) to human platelets as scIV.3 (Kd, 0.9 nM), and the binding of scIV.3-IdeS to human platelets was blocked by cIV.3 (Figure 2B).

Generation and characterization of recombinant scIV.3-IdeS. (A) Increasing concentrations of His-tagged scIV.3-IdeS or scIV.3 were incubated with human platelets and then stained with a fluorescently labeled anti-His Tag antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 4). (B) Microscopic images (60× objective) of platelets spread on fibrinogen treated with control or cIV.3 and costained with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) and an anti-CD41 antibody. (C) Surface-bound scIV.3-IdeS was quantified by flow cytometry every 30 minutes for 90 minutes. (D) Representative Coomassie-stained gel used to evaluate IgG cleavage after the incubation of IgG with predetermined concentrations of scIV.3, Ides, or scIV.3-IdeS. IdeS cleaves IgG in a 2-step process, first generating a single-cleaved IgG (scIgG) and then a double-cleaved F(ab′)2. The cleaved Fc fragment was quantified as a measure of IdeS activity. The relative fluorescence units of the Fc fragment were reported for 4 independent experiments (data given as mean ± standard deviation). *P < .05. RFLU, relative fluorescence units.

Generation and characterization of recombinant scIV.3-IdeS. (A) Increasing concentrations of His-tagged scIV.3-IdeS or scIV.3 were incubated with human platelets and then stained with a fluorescently labeled anti-His Tag antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 4). (B) Microscopic images (60× objective) of platelets spread on fibrinogen treated with control or cIV.3 and costained with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) and an anti-CD41 antibody. (C) Surface-bound scIV.3-IdeS was quantified by flow cytometry every 30 minutes for 90 minutes. (D) Representative Coomassie-stained gel used to evaluate IgG cleavage after the incubation of IgG with predetermined concentrations of scIV.3, Ides, or scIV.3-IdeS. IdeS cleaves IgG in a 2-step process, first generating a single-cleaved IgG (scIgG) and then a double-cleaved F(ab′)2. The cleaved Fc fragment was quantified as a measure of IdeS activity. The relative fluorescence units of the Fc fragment were reported for 4 independent experiments (data given as mean ± standard deviation). *P < .05. RFLU, relative fluorescence units.

The ability of scIV.3-IdeS to degrade surface-bound IgG is predicated on it being retained on the cell surface; however, previous work demonstrated engagement of FcγRIIA with divalent IV.3 caused receptor internalization.14 We therefore sought to determine whether our monovalent ligand, scIV.3, caused receptor internalization when engaging FcγRIIA. We incubated the lowest concentration of His-tagged scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) that caused full receptor occupancy on human platelets for up to 90 minutes. Surface-bound scIV.3-IdeS was similar at all time points tested as measured by flow cytometry (Figure 2C). However, the cross-linking of platelet FcγRIIA with IV.3 and a goat anti-mouse antibody caused 70% of the receptor to be internalized after 90 minutes (supplemental Figure 1). These data support the notion that FcγRIIA-bound scIV.3-IdeS remained on the surface of platelets for the duration of our in vitro studies.

To test whether the fusion of IV.3 to the N-terminus of IdeS affected its enzymatic activity, human IgG was incubated with increasing concentrations of either IdeS or scIV.3-IdeS. IdeS digests the heavy chains of IgG in a 2-step process, with the cleavage of the first heavy chain proceeding roughly 100-fold faster than that of the second.23 The samples were then run on a 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel under nonreducing conditions, and the formation of the Fc cleavage product of IgG was quantified. Similar amounts of IgG were cleaved by IdeS and scIV.3-IdeS at 100 nM, resulting mostly in a single-chain cleavage (Figure 2D). Minimal IgG cleavage was observed at 10 or 1 nM by either IdeS or scIV.3-IdeS (Figure 2D). Importantly, scIV.3 by itself was unable to cleave IgG (Figure 2D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the fusion of scIV.3 and IdeS does not appreciably alter the binding affinity of scFv or the cleavage capacity of IdeS.

scIV.3-IdeS inhibits IgG-mediated platelet aggregation more potently than scIV.3 alone

On platelets, IgG-dependent clustering of FcγRIIA causes platelet activation, but FcγRIIA has also been implicated in IgG-independent potentiation of integrin αIIbβ3 signaling.24,25 To examine whether scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS binding to FcγRIIA alters platelet activation, PRP was stimulated with either ADP or collagen. As expected, scIV.3 and scIV.3-IdeS, but not the control, inhibited anti-CD9 antibody–mediated platelet aggregation (Figure 3A). However, neither scIV.3 nor scIV.3-IdeS inhibited platelet aggregation in response to collagen or ADP compared with vehicle control (Figure 3A), even at threshold concentrations of agonists (supplemental Figure 2).

scIV.3-IdeS inhibits IgG-mediated platelet aggregation more potently than scIV.3 alone. (A) PRP was incubated with scIV.3 (20 nM), scIV.3-IdeS (20 nM), or control and then stimulated with a mouse (Ms) anti-human CD9 antibody (Ms anti-hCD9; 1 μg/mL), ADP (20 μM), or collagen (1 μg/mL). Representative tracings for Ms anti-hCD9– and collagen-stimulated platelets were included, and maximum aggregation for 3 to 4 independent experiments was reported. (B) Washed platelets treated with 1, 2.5, or 20 nM of scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were stimulated with Ms anti-hCD9 (1 μg/mL), and maximum aggregation was reported. (C) Platelets treated with predetermined concentrations of scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were stimulated with rabbit (rb) anti-hCD9 (1 μg/mL), and maximum aggregation was reported (data shown as mean ± SD; 1-way analysis of variance; n = 3-4). #P < .05 (statistical difference between treated and control [0 nm]), ****P < .0001.

scIV.3-IdeS inhibits IgG-mediated platelet aggregation more potently than scIV.3 alone. (A) PRP was incubated with scIV.3 (20 nM), scIV.3-IdeS (20 nM), or control and then stimulated with a mouse (Ms) anti-human CD9 antibody (Ms anti-hCD9; 1 μg/mL), ADP (20 μM), or collagen (1 μg/mL). Representative tracings for Ms anti-hCD9– and collagen-stimulated platelets were included, and maximum aggregation for 3 to 4 independent experiments was reported. (B) Washed platelets treated with 1, 2.5, or 20 nM of scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were stimulated with Ms anti-hCD9 (1 μg/mL), and maximum aggregation was reported. (C) Platelets treated with predetermined concentrations of scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were stimulated with rabbit (rb) anti-hCD9 (1 μg/mL), and maximum aggregation was reported (data shown as mean ± SD; 1-way analysis of variance; n = 3-4). #P < .05 (statistical difference between treated and control [0 nm]), ****P < .0001.

To determine whether scIV.3-IdeS neutralizes IgG under biologically relevant conditions, subsaturating concentrations of scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were bound to the platelet surface, and platelets were then stimulated with anti-CD9 IgG antibodies. The inhibitory effects of scIV.3 and scIV.3-IdeS on FcγRIIA-dependent platelet activation were similar in platelets stimulated with mouse anti-CD9 antibodies, which cannot be cleaved by IdeS (Figure 3B). When platelets were incubated with IdeS-cleavable rabbit anti-CD9 antibodies, scIV.3-IdeS, but not scIV.3, was able to inhibit aggregation at 1 and 2.5 nM (Figure 3C). Higher concentrations (20 nM) of either scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS that saturated the receptor were able to inhibit rabbit anti-human CD9–mediated platelet activation. scIV.3 and scIV.3-IdeS bound with similar affinity to FcγRIIA, but the conjugation of IdeS to scIV.3 enhanced its ability to prevent aggregation mediated by cleavable (rabbit) IgG, but not uncleavable (mouse) IgG.

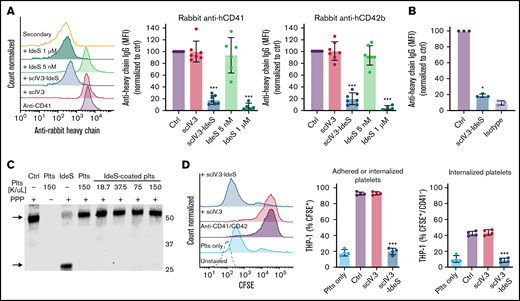

Targeting scIV.3-IdeS to platelet FcγRIIA cleaves antiplatelet antibodies and prevents platelet phagocytosis

To examine whether scIV.3-IdeS anchored to the surface of platelets could neutralize antiplatelet IgG, scIV.3-IdeS–treated platelets were incubated with polyclonal rabbit IgG specific for human CD41 or CD42b, and IgG cleavage and in vitro phagocytosis were measured. As expected, the amount of intact anti-human CD41 and CD42b antibodies bound to platelets treated with scIV.3 (5 nM) or vehicle control was the same, as determined by flow cytometry with an anti-rabbit IgG heavy chain–specific antibody (Figure 4A). In contrast, platelets with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) on their surface had a decrease in the binding of intact anti-CD41 or anti-CD42b antibodies (Figure 4A). Interestingly, equal concentrations of nontargeted IdeS (5 nM) were unable to degrade antiplatelet IgG; however, higher concentrations of nontargeted IdeS were able to cleave antiplatelet IgG (Figure 4A). To assess whether scIV.3-IdeS could cleave IgG on the surface of platelets precoated in antiplatelet antibodies, platelets were incubated with polyclonal rabbit IgG specific for human CD41, washed, and treated with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM). Antibody-coated platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS for 30 minutes had a reduction of ∼80% in surface-bound heavy chain IgG compared with control (Figure 4B). To examine whether scIV.3-IdeS–coated platelets caused collateral IgG degradation, scIV.3-IdeS–coated platelets were incubated with platelet-poor plasma for 1 hour. IgG cleavage (∼30-kDa fragment) was not detected at any of the scIV.3-IdeS–coated platelet concentrations tested (0.375 to 1.5 × 108 platelets per mL; Figure 4C). An antibody-dependent in vitro phagocytosis assay was then performed to explore the physiological relevance of the reduction in heavy chain bound to platelets. CFSE-stained platelets were incubated with a combination of CD41 and CD42b polyclonal antibodies in the presence of scIV.3, scIV.3-IdeS, or control and then added to PMA-activated THP-1 cells. The number of THP-1 cells with surface-adhered or internalized CFSE+ platelets was decreased in platelets with surface-bound IdeS compared with platelets treated with scIV.3 or control (Figure 4D). Furthermore, compared with platelets treated with scIV.3 or control, fewer scIV.3-IdeS–treated platelets were phagocytosed by THP-1 cells (CFSE+/CD42a−) in the presence of antiplatelet antibodies (Figure 4D).

scIV.3-IdeS bound to platelet FcγRIIA cleaves antiplatelet antibodies and prevents in vitro phagocytosis. (A) Platelets treated with scIV.3 (5 nM), IdeS, and scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) were incubated with rabbit anti-human CD41 or CD42b antibodies, and the amount of undigested antibody bound to platelets was quantified by flow cytometry with an anti-rabbit heavy chain antibody. Data normalized to control median fluorescence intensity (MFI). (B) Platelets coated in rabbit anti-human CD41 polyclonal antibodies were treated with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) or control. The amount of undigested antibody bound to platelets was quantified by flow cytometry using an antibody specific for the heavy chain of rabbit IgG. (C) Human IgG western blot, representative of 3 independent experiments, of platelet-poor plasma (PPP) incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-IdeS–coated platelets (18.7-150 × 106/mL) for 1 hour. PPP was also incubated with control, untreated platelets, or IdeS (1 μM). IdeS-treated samples lacked the full-length IgG heavy chain (arrow; upper band) and had an Fc cleavage product (arrow; lower band). (D) CFSE-stained platelets treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS in the presence of rabbit anti-human (CD41 and CD42b) antibodies were added to THP-1 cells. After 1 hour, THP-1 cells were stained with a platelet-specific (PE-conjugated CD42a) antibody to distinguish THP-1 cells that had adhered (CFSE+/CD42a+) or internalized (CFSE+/CD42a−) platelets (data represent mean ± standard deviation; 1-way analysis of variance; n = 4). *P < .05, ***P < .001.

scIV.3-IdeS bound to platelet FcγRIIA cleaves antiplatelet antibodies and prevents in vitro phagocytosis. (A) Platelets treated with scIV.3 (5 nM), IdeS, and scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) were incubated with rabbit anti-human CD41 or CD42b antibodies, and the amount of undigested antibody bound to platelets was quantified by flow cytometry with an anti-rabbit heavy chain antibody. Data normalized to control median fluorescence intensity (MFI). (B) Platelets coated in rabbit anti-human CD41 polyclonal antibodies were treated with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) or control. The amount of undigested antibody bound to platelets was quantified by flow cytometry using an antibody specific for the heavy chain of rabbit IgG. (C) Human IgG western blot, representative of 3 independent experiments, of platelet-poor plasma (PPP) incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-IdeS–coated platelets (18.7-150 × 106/mL) for 1 hour. PPP was also incubated with control, untreated platelets, or IdeS (1 μM). IdeS-treated samples lacked the full-length IgG heavy chain (arrow; upper band) and had an Fc cleavage product (arrow; lower band). (D) CFSE-stained platelets treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS in the presence of rabbit anti-human (CD41 and CD42b) antibodies were added to THP-1 cells. After 1 hour, THP-1 cells were stained with a platelet-specific (PE-conjugated CD42a) antibody to distinguish THP-1 cells that had adhered (CFSE+/CD42a+) or internalized (CFSE+/CD42a−) platelets (data represent mean ± standard deviation; 1-way analysis of variance; n = 4). *P < .05, ***P < .001.

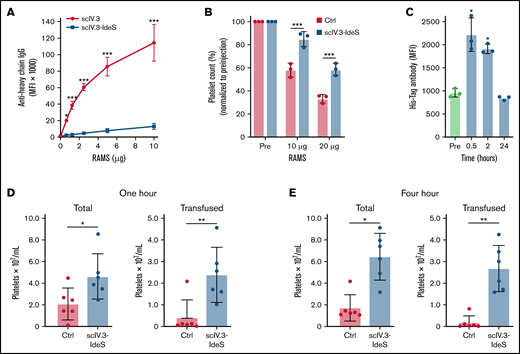

IdeS-IV.3–treated platelets have increased survival in murine models of ITP

To determine the effectiveness of scIV.3-IdeS–coated platelets to cleave polyclonal rabbit antiplatelet IgG in vitro, increasing concentrations of RAMS were incubated with platelets isolated from mice expressing human FcγR receptors. Even at the highest concentration of RAMS tested (10 μg), platelets coated in scIV.3-IdeS had a decrease of ∼90% in full-length antibody bound compared with scIV.3-treated platelets (Figure 5A). To test whether scIV.3-IdeS prevented platelet clearance in vivo, mice expressing human FcγRIIA were injected with scIV.3-IdeS (10 μg) or buffer control and, 30 minutes later, intraperitoneally injected with 10 or 20 μg of rabbit anti-mouse platelet sera. After 24 hours, mice treated with scIV.3-IdeS had a higher platelet count than control-treated mice (Figure 5B). The binding of scIV.3-IdeS to platelets in mice was measured at 0.5, 2, and 24 hours postinjection. There was a significant increase in scIV.3-IdeS binding to platelets at 0.5 and 2 hours, but not 24 hours (Figure 5C). To model antibody-mediated platelet refractoriness, mice were intraperitoneally injected with RAMS 24 hours before being transfused with CFSE-labeled hFcγRIIA+ platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS or control. At 1 and 4 hours posttransfusion, the total amount of platelets was increased in mice transfused with scIV.3-IdeS–treated platelets compared with control (Figure 5D-E). Additionally, transfused platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS were protected from clearance compared with control-treated platelets (Figure 5D-E).

IdeS-IV.3–treated platelets have increased survival in murine models of ITP. (A) Mouse platelets expressing FcγRIIA were treated in vitro with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS and then incubated with increasing concentrations of RAMS, and full-length platelet-bound IgG was measured (n = 3). (B) Mice expressing human Fc receptors were treated with control or IV.3-IdeS (10 μg) and then injected with 10 or 20 μg of RAMS. Platelet counts were performed 24 hours after RAMS injection and were normalized to pre-IgG injection (pre) measurements. (C) The amount of surface-bound His-tagged scIV.3-IdeS on mouse platelets was quantified by flow cytometry 0.5, 2, and 24 hours after IV.3-IdeS treatment. CFSE-labeled mouse platelets expressing FcγRIIA were treated with scIV.3-IdeS or control and transfused into mice that were injected with RAMS 24 hours before transfusion. (D-E) The total and transfused platelet counts were measured using a Cytek Aurora flow cytometer at 1 (D) and 4 hours (E) posttransfusion (data represent mean ± standard deviation; 1-way analysis of variance). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

IdeS-IV.3–treated platelets have increased survival in murine models of ITP. (A) Mouse platelets expressing FcγRIIA were treated in vitro with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS and then incubated with increasing concentrations of RAMS, and full-length platelet-bound IgG was measured (n = 3). (B) Mice expressing human Fc receptors were treated with control or IV.3-IdeS (10 μg) and then injected with 10 or 20 μg of RAMS. Platelet counts were performed 24 hours after RAMS injection and were normalized to pre-IgG injection (pre) measurements. (C) The amount of surface-bound His-tagged scIV.3-IdeS on mouse platelets was quantified by flow cytometry 0.5, 2, and 24 hours after IV.3-IdeS treatment. CFSE-labeled mouse platelets expressing FcγRIIA were treated with scIV.3-IdeS or control and transfused into mice that were injected with RAMS 24 hours before transfusion. (D-E) The total and transfused platelet counts were measured using a Cytek Aurora flow cytometer at 1 (D) and 4 hours (E) posttransfusion (data represent mean ± standard deviation; 1-way analysis of variance). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Platelets with surface-bound IdeS neutralize the Fc-dependent effector functions of ITP and HIT antibodies

Platelets with surface-bound IdeS efficiently cleaved and neutralized the Fc-dependent effector functions of commercial polyclonal antiplatelet antibodies. Therefore, we next wanted to determine whether platelets with surface-bound IdeS could neutralize the Fc-dependent effector functions of antibodies from patients with HIT or ITP. Previously established platelet factor 4–dependent P-selectin surface expression assays were used to test the ability of scIV.3-IdeS to block HIT IgG-mediated platelet activation.26 Platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS had decreased HIT IgG-mediated P-selectin surface expression compared with vehicle control–treated platelets (Figure 6A). Platelets from healthy donors were incubated with sera from 4 patients with ITP, and the amount of intact antiplatelet antibodies remaining on the platelet surface after treatment with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) was quantified by flow cytometry using an anti-human Fc-specific antibody. The binding of full-length antiplatelet antibodies from the sera of all 4 patients was significantly reduced in platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS compared with control (Figure 6B). To examine whether scIV.3 alone had an impact on HIT IgG-mediated platelet activation or prevented antiplatelet antibodies from binding platelets, respectively, platelets treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were exposed to sera from patients with HIT or ITP. scIV.3 inhibited HIT IgG-mediated platelet activation (Figure 6C), but not the binding of antiplatelet IgG to platelets (Figure 6D). CFSE-stained platelets were incubated with sera from 4 separate patients with ITP in the presence or absence of scIV.3-IdeS and added to PMA-activated THP-1 cells. Platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS had a significant decrease in the number of platelets adherent to or internalized by activated THP-1 cells in 3 of the 4 ITP samples tested (Figure 6E). Interestingly, antibodies from ITP patient 2 bound to platelets (Figure 6B) but did not result in phagocytosis. scIV.3-IdeS–treated platelets decreased platelet phagocytosis in samples from 2 ITP donors (Figure 6E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that platelet-targeted IdeS can neutralize the Fc-dependent effector functions of ITP and HIT antibodies from patient sera.

scIV.3-IdeS bound to platelet FcγRIIA cleaves antiplatelet antibodies from HIT and ITP sera and prevents in vitro phagocytosis. (A) Platelet factor 4 (PF4)–dependent P-selectin expression assays were performed using sera from 5 patients with HIT and platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) or vehicle. (B) Platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS or vehicle control were incubated with sera from patients with ITP, stained with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated mouse anti-human Fc-specific antibody, and quantified by flow cytometry (data represent mean ± standard deviation [SD]; 2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]; n = 4-6). (C) PF4-dependent P-selectin expression assay was performed with platelets treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS using sera from a patient with HIT. (D) Platelets treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were incubated with sera from a patient with ITP and then stained with an FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human Fc-specific antibody. (E) CFSE-stained human platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) or vehicle control were incubated with sera from patients with ITP and were then added to THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were stained with a platelet-specific (PE-conjugated CD42a) antibody to distinguish THP-1 cells that had adhered (CFSE+/CD42a+) or internalized (CFSE+/CD42a−) platelets (data represent mean ± SD; 1-way ANOVA; n = 4). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

scIV.3-IdeS bound to platelet FcγRIIA cleaves antiplatelet antibodies from HIT and ITP sera and prevents in vitro phagocytosis. (A) Platelet factor 4 (PF4)–dependent P-selectin expression assays were performed using sera from 5 patients with HIT and platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) or vehicle. (B) Platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS or vehicle control were incubated with sera from patients with ITP, stained with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated mouse anti-human Fc-specific antibody, and quantified by flow cytometry (data represent mean ± standard deviation [SD]; 2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]; n = 4-6). (C) PF4-dependent P-selectin expression assay was performed with platelets treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS using sera from a patient with HIT. (D) Platelets treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were incubated with sera from a patient with ITP and then stained with an FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human Fc-specific antibody. (E) CFSE-stained human platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) or vehicle control were incubated with sera from patients with ITP and were then added to THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were stained with a platelet-specific (PE-conjugated CD42a) antibody to distinguish THP-1 cells that had adhered (CFSE+/CD42a+) or internalized (CFSE+/CD42a−) platelets (data represent mean ± SD; 1-way ANOVA; n = 4). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Discussion

IdeS is a promising new therapy for treating IgG-driven disorders, but its adverse effects limit current clinical use to sensitized kidney transplantation patients. In this study, we found that recombinant IdeS, modified to bind to FcγRIIA (scIV.3-IdeS), cleaved antiplatelet IgG, blocked FcγRIIA-mediated platelet activation, and prevented phagocytosis in vitro without a significant decrease in nonpathogenic IgG. Moreover, in passive murine models of ITP, transfused platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS had prolonged circulation compared with control. Together, these results suggest that anchoring IdeS to transfused platelets to prolong their circulation could represent a life-saving treatment for patients with severe bleeding and IgG-mediated platelet transfusion refractoriness.

Although both Fc receptor–dependent and –independent platelet clearance occurs in patients with ITP, the Fc receptors on macrophages in the reticuloendothelial system are primarily responsible for the clearance of IgG-coated platelets.27-29 A single IdeS molecule cleaves >2000 IgG molecules; anchoring IdeS to FcγRIIA (1000-5000 copies per platelet) should provide sufficient coverage to digest all bound antiplatelet IgG.30 In our study, we found that platelet-bound IdeS could remove the Fc portion of antiplatelet IgG from platelets and prevent them from being phagocytosed by the macrophages in vitro. Interestingly, we found that scIV.3-IdeS could cleave IgG from the surface of platelets whether it was added before or after the platelets were coated with antiplatelet antibodies. The ability of scIV.3-IdeS to protect transfused platelets from clearance in a murine model of ITP with polyclonal rabbit antibodies against multiple platelet antigens suggests that scIV.3-IdeS can broadly neutralize antiplatelet IgG regardless of antibody specificity.

We observed that prophylactic IV injection of scIV.3-IdeS into mice with human Fc receptors reduced platelet clearance in a passive model of ITP using RAMS to multiple platelet antigens (Figure 5). One potential limitation of directly administering scIV.3-IdeS is whether IdeS bound to the surface of macrophages alters antibody-mediated phagocytosis of pathogens. The localization of IdeS to the surface of platelets seems to be advantageous in limiting the clearance of nonpathogenic IgG and could conceivably be achieved by targeting platelet-specific receptors, such as αIIb, GPVI, or GPIb/V/IX. However, these platelet-specific targets for IdeS were avoided in this study because of concerns scFv could impair hemostasis or sterically hinder antiplatelet IgG from binding platelets, which could prevent the antiplatelet IgG from being cleaved. Additional studies will be needed to determine the optimal means of targeting IdeS to the platelet surface.

A targeted IdeS therapeutic approach could expand the clinical indications of IdeS for ITP as well as other IgG-mediated disorders. Among patients with anti–glomerular basement membrane antibodies treated with IdeS, >50% had their pathogenic antibodies return to toxic levels and had to resume conventional treatments to decrease pathogenic antibodies.8,31 Anchoring IdeS to a cellular target can lower the dose of IdeS and may allow the administration of repeated doses of IdeS. Future work will focus on determining the impact that targeting IdeS to the surface of platelets has on its immunogenicity in animal models, especially after multiple doses.

Phagocytosis of platelets incubated with rabbit anti-CD41 and anti-CD42 antibodies by THP-1 cells was profoundly reduced by scIV.3-IdeS. In all samples from patients with ITP tested, there was a considerable decrease in full-length antibody binding to platelets coated with IdeS, and this was effective in significantly reducing phagocytosis in 2 of 3 patient samples. Future studies to elucidate the broad therapeutic potential of scIV.3-IdeS in patients with ITP must examine patient sera with high titers of antibody or different antigenic targets yielding unique pathogenic antibodies on the surface of platelets. Furthermore, although a majority of antiplatelet antibodies in patients with ITP are IgG, sporadic cases of antiplatelet IgM or IgA antibodies have also been detected in these patients.27 Because IdeS cleavage is IgG specific, individuals with ITP mediated by IgM or IgA ITP antibodies would not benefit from scIV.3-IdeS treatment.

Platelet clearance and activation can occur in autoimmune disorders through the formation of immune complexes that activate platelets via FcγRIIA.32,33 IV.3 can block IgG-mediated platelet activation and thrombosis.34 In this study, we show that scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS blocks FcγRIIA-mediated platelet activation via anti-CD9 antibodies and sera from patients with HIT. scIV.3-IdeS was more effective at blocking FcγRIIA-mediated platelet activation than scIV.3 at concentrations in which platelet FcγRIIA was not fully occupied (Figure 3). The cleavage of pathogenic IgG complexes by platelets coated in scIV.3-IdeS can neutralize IgG complexes from activating platelets, potentially extending to platelet protection even after scIV.3-IdeS has been cleared. Future experiments must be performed to determine whether scIV.3-IdeS offers heightened protection from IgG complex–mediated thrombosis in murine models compared with scIV.3.

The use of scIV.3-IdeS alone or in conjunction with corticosteroids could be a minimally invasive approach to raise platelet counts in patients with ITP. Furthermore, other acute IgG-driven platelet diseases with clearly defined Fc-dependent pathogenesis, such as vaccine-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis35 or HIT, would be predicted to respond to scIV.3-IdeS therapy. Pretreatment of platelets with scIV.3-IdeS before transfusion could also provide a means of rapidly raising the platelet count in patients with severe bleeding who have ITP or platelet refractoriness as a result of alloimmunization. Importantly, adapting cell type–specific targeting of IdeS to treat other IgG-mediated immune disorders is practical depending on tissue accessibility and identification of cell type–specific ligands that can be targeted with high affinity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jeffrey V. Ravetch for providing mice that express human Fcγ receptors and Eric Smith for help in editing the manuscript. All flow cytometric data were acquired using equipment maintained by the Research Flow Cytometry Core in the Division of Rheumatology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The visual abstract was created with BioRender.com.

This work was funded in part through National Institutes of Health grants from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute R00 HL136784 (B.E.T.), K23HL151872 (D.R.L.), Office of Research Infrastructure Programs S10OD025045 (Research Flow Cytometry Core), and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Cooperative Centers of Excellence in Hematology grant U54DK126108; and a Trustee Grant Award from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital (B.E.T.).

Authorship

Contribution: D.R.L., E.N.S., B.Z., C.F.G., and B.E.T. acquired and analyzed data; and D.R.L., E.N.S., G.B.-C., B.R.C., C.F.G., B.E.T., and J.S.P. designed research studies and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.R.C. is a consultant for Rallybio and argenx. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Benjamin E. Tourdot, Division of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, MLC 7015, Cincinnati, OH 45229; e-mail: benjamin.tourdot@cchmc.org.

References

Author notes

For data sharing, please contact the corresponding author at benjamin.tourdot@cchmc.org.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Characterization of the binding properties of scIV.3. (A) Increasing concentrations of FAM-conjugated scIV.3 (scIV.3-FAM) were incubated with platelets from wild-type mice (hFcγRIInull) or hFcγRIIA transgenic mice (hFcγRIIATGN), and the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 3 independent experiments was reported. (B) Representative histograms of THP-1 cells stained with select concentrations of scIV.3-FAM. THP-1 cells (green dashed line) or human platelets (black line) were incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-FAM, and data are reported as percentage of maximum MFI for each cell type (n = 3-4). (C) Representative microscopic images (60× objective) of human platelets (CD41+) spread on fibrinogen, treated with control or cIV.3 (30 nM), and then stained with scIV.3-FAM (5 nM). (D) Flow cytometry was used to quantify the binding of scIV.3-FAM to human platelets after incubation with or without cIV.3 (data represent n = 4; mean ± standard deviation [SD]). (E) Human whole blood was incubated with increasing concentrations of scIV.3-FAM and normalized to cIV.3 (30 nM). (F) Human platelets were treated with scIV.3 (50 nM) or control and then stimulated with mouse anti-human CD9 antibodies, an FcγRIIA-specific agonist (data represent n = 5; mean ± SD). Two-way statistical analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction was performed. Kd, distribution coefficient. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/6/15/10.1182_bloodadvances.2022007195/3/m_advancesadv2022007195f1.png?Expires=1765891742&Signature=b~1cxDLxM~dJURwM7tEyXUVS8bMfAjdCIGUTvW4fasXt4oSOepqh9cFanKx0nXzGCbntqetfly8oVpdSx-Bo~mk5za3IX6kb7l0Tb1P9dvei-WAkaqH85N2wIuhx1EzfZSq2uNL3tfLPlt0LCoLwvgw4lu3TMF~lrU8pGNq9Lc4RDiRMt-NJPyWY5s8K9G2vwL0X0oHg8Nwma5D8-MMn0VQTPAPEs8RLHh5PhEU9-Q1HNFcDvEK6Q-PX2Bz0cAC9rzCbg4wvOkrTMXi8VqsgYNU0yaVH8~7D06PSDdxAUGkp7fU0jqEibKMe8~xgulJsbd7ZYvI4NNErlWIG-HRKNg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![scIV.3-IdeS inhibits IgG-mediated platelet aggregation more potently than scIV.3 alone. (A) PRP was incubated with scIV.3 (20 nM), scIV.3-IdeS (20 nM), or control and then stimulated with a mouse (Ms) anti-human CD9 antibody (Ms anti-hCD9; 1 μg/mL), ADP (20 μM), or collagen (1 μg/mL). Representative tracings for Ms anti-hCD9– and collagen-stimulated platelets were included, and maximum aggregation for 3 to 4 independent experiments was reported. (B) Washed platelets treated with 1, 2.5, or 20 nM of scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were stimulated with Ms anti-hCD9 (1 μg/mL), and maximum aggregation was reported. (C) Platelets treated with predetermined concentrations of scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were stimulated with rabbit (rb) anti-hCD9 (1 μg/mL), and maximum aggregation was reported (data shown as mean ± SD; 1-way analysis of variance; n = 3-4). #P < .05 (statistical difference between treated and control [0 nm]), ****P < .0001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/6/15/10.1182_bloodadvances.2022007195/3/m_advancesadv2022007195f3.png?Expires=1765891742&Signature=2mQ1DLhCh64zhsl1KLUyn6hBwBoPvQdjU~6QEE5-uwPHioH6VJgV-hMqObJY~wojSlZFH3lldYOtEajgiB~GFwTSw96UE2D2GpObKJ3uY2OWod13locnpN77fwroWTJcu7GriPADgtqKDdC71~34Q8KDW2PHF3tlhOQElhpahm6WefjPBUL-o20xZ0yvHTFbEU0c127lOiwtUV1zB2azqFdrNf3dFd6O2f~5jTw6UUfK0X-zDwLDfCZOYAAfxPKvmhbUN5sQx9tEdo4152bHFcltCI8Bvxe3FKerAytL0vmccaLMzsG~VuIes3EvCejY1C8j3Nfi4yGuWSrvbc9vGg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![scIV.3-IdeS bound to platelet FcγRIIA cleaves antiplatelet antibodies from HIT and ITP sera and prevents in vitro phagocytosis. (A) Platelet factor 4 (PF4)–dependent P-selectin expression assays were performed using sera from 5 patients with HIT and platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) or vehicle. (B) Platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS or vehicle control were incubated with sera from patients with ITP, stained with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated mouse anti-human Fc-specific antibody, and quantified by flow cytometry (data represent mean ± standard deviation [SD]; 2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]; n = 4-6). (C) PF4-dependent P-selectin expression assay was performed with platelets treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS using sera from a patient with HIT. (D) Platelets treated with scIV.3 or scIV.3-IdeS were incubated with sera from a patient with ITP and then stained with an FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human Fc-specific antibody. (E) CFSE-stained human platelets treated with scIV.3-IdeS (5 nM) or vehicle control were incubated with sera from patients with ITP and were then added to THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were stained with a platelet-specific (PE-conjugated CD42a) antibody to distinguish THP-1 cells that had adhered (CFSE+/CD42a+) or internalized (CFSE+/CD42a−) platelets (data represent mean ± SD; 1-way ANOVA; n = 4). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/6/15/10.1182_bloodadvances.2022007195/3/m_advancesadv2022007195f6.png?Expires=1765891742&Signature=2jRUEUmqYjoYlcUOcbz2O89NzLrGTt5waG1Spa-I8Aj9zpVzmDl05ZT4yzPg~jmd5eLCp~chDi95SEnGqMxGf4XuT9PXrSY6MnzuCITxiTm1HugxxOKrdjnkyXTw6Q~juuImRPxsjYIGOzM8Z1D0Hay7x-pPe95~AUlfzZUDnigqoOkGSAhOxFZ91oD2Jnnsz1LHg-SULFAtbX~dvxcNpY6NDQV-Za2raEZZV-MWVfpOdhDRH7o0BVedpbQucQyVrcXR6ga6vGmF7dOMyRNnRmwY3onWKfBiSGSBe91w9cs4SnwqAOKIX6fWD-CNQqVXXjPbOtYaWQOKqzrlSrmiVA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)