Key Points

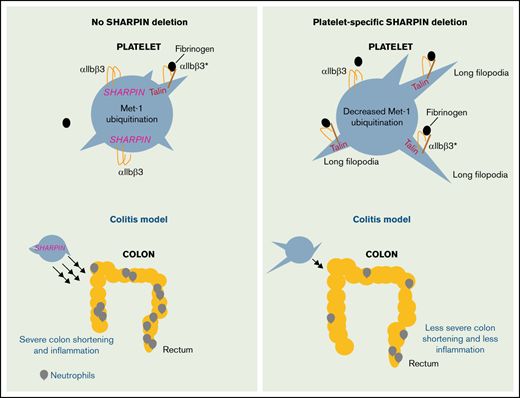

Platelet SHARPIN negatively regulates integrin αIIbβ3 function.

Platelet SHARPIN positively regulates inflammatory responses.

Abstract

Platelets form hemostatic plugs to prevent blood loss, and they modulate immunity and inflammation in several ways. A key event during hemostasis is activation of integrin αIIbβ3 through direct interactions of the β3 cytoplasmic tail with talin and kindlin-3. Recently, we showed that human platelets express the adapter molecule Shank-associated RH domain interacting protein (SHARPIN), which can associate directly with the αIIb cytoplasmic tail and separately promote NF-κB pathway activation as a member of the Met-1 linear ubiquitination activation complex (LUBAC). Here we investigated the role of SHARPIN in platelets after crossing Sharpin flox/flox (fl/fl) mice with PF4-Cre or GPIbα-Cre mice to selectively delete SHARPIN in platelets. SHARPIN-null platelets adhered to immobilized fibrinogen through αIIbβ3, and they spread more extensively than littermate control platelets in a manner dependent on feedback stimulation by platelet adenosine diphosphate (ADP) (P < .01). SHARPIN-null platelets showed increased colocalization of αIIbβ3 with talin as assessed by super-resolution microscopy and increased binding of soluble fibrinogen in response to submaximal concentrations of ADP (P < .05). However, mice with SHARPIN-null platelets showed compromised thrombus growth on collagen and slightly prolonged tail bleeding times. Platelets lacking SHARPIN also showed reduced NF-κB activation and linear ubiquitination of protein substrates upon challenge with classic platelet agonists. Furthermore, the loss of platelet SHARPIN resulted in significant reduction in inflammation in murine models of colitis and peritonitis (P < .01). Thus, SHARPIN plays differential and context-dependent roles in platelets to regulate important inflammatory and integrin adhesive functions of these anucleate cells.

Introduction

Platelet function in hemostasis and thrombosis is largely controlled through receptors in the platelet plasma membrane that sample the extracellular space for specific agonists and adhesive proteins. Consequently, platelet adhesion and aggregation result when stimulatory signals overcome inherent negative regulatory controls.1,2 Integrin αIIbβ3 is central to platelet spreading and aggregation after vascular injury.3 Activation of αIIbβ3 involves its conversion from a bent conformation with closed headpiece to an extended, open high-affinity conformation to allow binding of soluble fibrinogen or von Willebrand factor, and it depends on interactions of intracellular talin and kindlin-3 with the β3 cytoplasmic tail.4,5 However, there remains incomplete understanding of how these intracellular positive integrin regulators and other potential negative regulators6-8 act in concert to control platelet function. In addition to their role in hemostasis, platelets are also key regulators of innate and adaptive immune responses not only because of their capacity to interact with almost all other known immune cells9 but also in their own right acting through additional platelet surface receptors, such as toll-like receptors, CD40, and chemokine receptors.10,11

The Shank-associated RH domain interacting protein (SHARPIN) is a 40-kDa protein that associates with integrin α subunit cytoplasmic tails, including the platelet-specific αIIb tail, at conserved membrane-proximal tail residues (W/yKXGFFKR).7,8 Additionally, SHARPIN, together with HOIL-1 and the ring-between-ring E3 ligase, HOIP, forms the LUBAC that polyubiquitinates a number of proteins at their N-terminal methionine (Met-1) residues and regulates classic activation of NF-κB.12-15 SHARPIN interactions with HOIP and integrin α-tails involve overlapping binding sites, suggesting possible competition and crosstalk between its integrin and NF-κB regulatory functions16 . We recently demonstrated that all 3 proteins of the LUBAC complex are expressed in human platelets and that LUBAC mediates Met-1 ubiquitination of the NF-κB pathway regulator, IKKγ (NEMO), in response to platelet agonists.7 Global deletion of SHARPIN occurs in cpdm mice that harbor a naturally occurring null mutation in the Sharpin gene, and these mice suffer from chronic dermatitis and widespread secondary lymphoid organ inflammation.17,18 In contrast, overexpression of SHARPIN has been observed in some human cancers.19 shRNA-mediated knockdown of SHARPIN in megakaryocytes and platelets derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells results in increased basal and agonist-induced fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 and reduced Met-1 ubiquitination of NEMO.7 However, the potential functions of SHARPIN in mature platelets and how they may impact integrin adhesive function and inflammation in vivo are unknown. Therefore, in the present study we generated 2 independent Cre mouse strains to delete SHARPIN selectively in platelets to identify distinct functions of platelet SHARPIN in αIIbβ3-mediated responses and in inflammation. The results establish differential roles for platelet SHARPIN in αIIbβ3 and LUBAC functions, with implications for platelets as sentinels of the vasculature and as inflammatory cells.

Methods

Generation of SHARPINfl/fl mice

C57BL/6 SHARPINfl/fl mice were generated by Ozgene (Bentley DC, WA, Australia) under the direction of 2 of the authors (E.P. and J.I.) as described further in supplemental Methods. Mice were then crossed with Pf4-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME)20 or GPIbα-Cre mice21 to derive 2 independent megakaryocyte lineage-restricted deletion models of SHARPIN, and each was backcrossed for at least 6 generations.

Mouse platelet preparation

Whole blood was drawn into acid citrate dextrose anticoagulant by cardiac puncture in accordance with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Washed platelets were prepared as previously described22 and finally resuspended in Walsh buffer (137 mM of NaCl, 2.7 mM of KCl, 1 mM of MgCl2.6H2O, 3.3 mM of NaH2PO4.H2O, 3.8 mM of HEPES, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% dextrose).

Analyses of platelet spreading

Glass coverslips were precoated with 100 μg/mL of fibrinogen.23 Mouse platelets at 2 × 107/mL were then allowed to attach in the absence or presence of 300 μM of mouse PAR4 agonist peptide, AYPGKF, for 30 minutes at 37°C. Adherent platelets were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes, and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rat anti-αIIb antibody, and then spread platelets were imaged by deconvolution microscopy23 at the UCSD Core Microscopy Facility. No specific staining was observed with a control FITC-conjugated rat IgG antibody. To address the potential contribution of ADP or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase) to platelet spreading, unstimulated platelet suspensions were preincubated with 5 U/mL of apyrase, 100 nM of wortmannin, or dimethyl sulfoxide control for 15 minutes prior to plating on coverslips. Platelets adherent to fibrinogen were stained with primary antibodies against αIIb and talin and STED-compatible secondary antibodies, and they were visualized on a LEICA STED SP8 super-resolution confocal microscope. Full image acquisition and processing details are available in supplemental Methods.

Flow cytometry and platelet aggregometry

To evaluate activation of αIIbβ3, 45 μL of 3 × 107/mL mouse platelets were incubated in the presence or absence of the indicated agonists for 30 minutes at room temperature. Specific (EDTA-inhibitable) Alexa-647-fibrinogen binding to platelets was quantified using an Accuri flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA).23 Results for each data point are calculated as specific fibrinogen bound, normalized by the specific fibrinogen bound by Cre− platelets at the maximum agonist concentration tested. Platelet aggregation was assayed as previously described24 using platelet-rich plasma prepared from blood collected into 3.8% sodium citrate. Surface expression of CD41 (αIIb) or CD62P (P-selectin) was determined using appropriate antibodies (BD Biosciences).

Bleeding time assay

To determine bleeding times, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a solution containing 100 mg/kg of ketamine and 10 mg/kg of xylazine. Then mouse tails were snipped 3 mm from the end and immersed immediately in 0.9% saline at 37°C. The time to arrest of bleeding was recorded.

Shear flow studies

Whole blood was aspirated through μSlideVI0.1 flow chambers (iBidi, Grafelfing, Germany) using a peristaltic pump (KD Scientific, Holliston, MA). Blood volumes were adjusted to yield 2, 3, and 5 minutes of flow through channels coated with fibrinogen or fibrillar collagen followed by perfusion fixation with 3.7% formaldehyde. Attached platelets were stained and imaged as above. Further details are provided in supplemental Methods.

Colitis model

A dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) model of acute colitis was used.25,26 Mice 8 to 10 weeks of age were provided with autoclaved tap water with or without 2.4% DSS in cage bottles. After 7 days, all mice were provided with autoclaved water without DSS. Mice were weighed daily, and similar fluid consumption was confirmed. Nine days from the start of DSS administration, mice were euthanized, the body cavity was exposed, and the colon segment between the rectum and cecum was removed and measured using precision calipers. Calculation of the rectal bleeding score and colon histology score based on epithelial damage and leukocyte infiltration27 are described further in the supplemental Methods.

Peritonitis model

To assess leukocyte recruitment into the peritoneum after a sterile inflammatory stimulus,28 1 mL of autoclaved 4% thioglycollate medium (Difco, BD, Sparks, MD) or sterile saline was injected intraperitoneally into 6- to 8-week-old mice, and the mice were euthanized after 4 or 24 hours. Neutrophil numbers in the peritoneum were calculated as the total cell count in the lavage fluid multiplied by the percent neutrophils, the latter determined by imaging of Hema-3 stained cytospins on a Keyence BZX-700 microscope with a Plan Apo ×40 objective (Itaska, IL). Further details may be found in supplemental Methods.

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test and analysis of variance.

Results

Mice with inserted loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the Sharpin gene (supplemetal Figure 1A) were crossed with Pf4-Cre or GPIbα-Cre recombinase mice to delete SHARPIN in cells of the megakaryocytic lineage. Platelets for initial in vitro studies were obtained from crosses with canonical Pf4-Cre mice typically used for specific deletion of a platelet protein. However, due to reports of potential leakiness of this model, including in the myeloid and lymphocyte lineages,29 we also used recently developed GPIbα-Cre recombinase mice with highly specific megakaryocyte expression to further ensure platelet-specific deletion of SHARPIN. All resulting mice were viable and fertile and had peripheral blood cell counts within normal ranges (Table 1). Genotypes were verified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using DNA from ear clippings to detect Cre and loxP gene sequences (supplemental Figure 1B-C). Megakaryocyte lineage-specific excision of the Sharpin gene was confirmed by PCR using primers detecting loss of Sharpin exon 2 in Pf4-Cre+, day 13 fetal liver–derived megakaryocytes but not in PCR from fetuses or Pf4-Cre− megakaryocytes (supplemental Figure 1D). Western blots confirmed SHARPIN protein deletion in lysates prepared from SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ platelets but not the corresponding Cre− platelets (supplemental Figure 2A,D). HOIP levels were also greatly decreased in SHARPINfl/fl Cre+ platelets, as noted in cells from cpdm mice,17,18 reflecting the role of SHARPIN in stabilization of the LUBAC complex. Expression levels of the essential integrin-regulatory proteins, talin, Rap1, and kindlin-3 were also found to be comparable in SHARPINfl/fl Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl Cre+ platelets (supplemental Figure 2B-C and E-F).

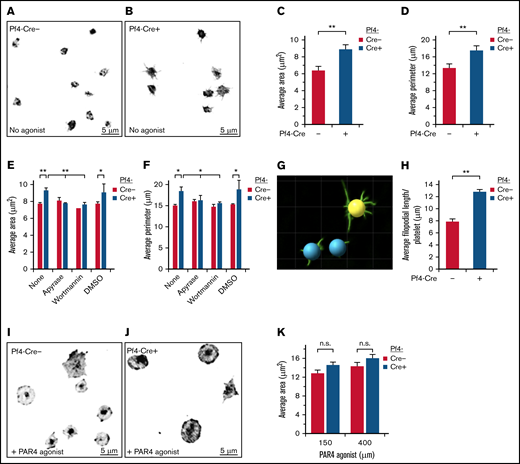

SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ platelets show increased spreading on immobilized fibrinogen. Unstimulated platelets were allowed to attach and spread for 30 minutes on fibrinogen, without (A-D) or with PAR4 agonist peptide (I-K) and then stained with an FITC-conjugated anti-αIIb antibody. Images were acquired on a deconvolution microscope with a ×100 oil objective, and the platelet area and perimeter were calculated using ImagePro software. (A,I) SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre−. (B, J) SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+. Average area (C,K) and average perimeter. n.s., not significant. (D) of spread platelets (n = 9). (E-F) Effect on platelet spreading of ADP and PI 3-kinase antagonists, apyrase, and wortmannin, respectively (n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01. (G) Surface rendering of αIIb fluorescence in platelets prepared (as in A-B) using Imaris software. (H) Quantification of average filopodial length per unstimulated αIIb-stained platelet calculated using Imaris rendering (as in G) (n = 5).

SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ platelets show increased spreading on immobilized fibrinogen. Unstimulated platelets were allowed to attach and spread for 30 minutes on fibrinogen, without (A-D) or with PAR4 agonist peptide (I-K) and then stained with an FITC-conjugated anti-αIIb antibody. Images were acquired on a deconvolution microscope with a ×100 oil objective, and the platelet area and perimeter were calculated using ImagePro software. (A,I) SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre−. (B, J) SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+. Average area (C,K) and average perimeter. n.s., not significant. (D) of spread platelets (n = 9). (E-F) Effect on platelet spreading of ADP and PI 3-kinase antagonists, apyrase, and wortmannin, respectively (n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01. (G) Surface rendering of αIIb fluorescence in platelets prepared (as in A-B) using Imaris software. (H) Quantification of average filopodial length per unstimulated αIIb-stained platelet calculated using Imaris rendering (as in G) (n = 5).

Blood cell counts

| . | GPIbα-Cre− . | GPIbα-Cre+ . |

|---|---|---|

| Red blood cells (M/μL) | 9.67 ± 0.7 | 9.98 ± 0.8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.2 ± 0.8 | 14.43 ± 0.9 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 48.3 ± 0.8 | 50.4 ± 4 |

| Platelets (K/μL) | 930 ± 63 | 843.3 ± 117 |

| Mean platelet volume (fL) | 7.40 ± 1.1 | 6.83 ± 0.6 |

| White blood cells (K/μL) | 5.80 ± 1.5 | 8.97 ± 1.6 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 26.6 ± 12 | 25.67 ± 17 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 71.3 ± 12 | 71.3 ± 17.5 |

| Monocytes (%) | 0.84 ± 0.4 | 1.02 ± 0.3 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1.24 ± 0.5 | 2.02 ± 0.7 |

| . | GPIbα-Cre− . | GPIbα-Cre+ . |

|---|---|---|

| Red blood cells (M/μL) | 9.67 ± 0.7 | 9.98 ± 0.8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.2 ± 0.8 | 14.43 ± 0.9 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 48.3 ± 0.8 | 50.4 ± 4 |

| Platelets (K/μL) | 930 ± 63 | 843.3 ± 117 |

| Mean platelet volume (fL) | 7.40 ± 1.1 | 6.83 ± 0.6 |

| White blood cells (K/μL) | 5.80 ± 1.5 | 8.97 ± 1.6 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 26.6 ± 12 | 25.67 ± 17 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 71.3 ± 12 | 71.3 ± 17.5 |

| Monocytes (%) | 0.84 ± 0.4 | 1.02 ± 0.3 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1.24 ± 0.5 | 2.02 ± 0.7 |

Platelet SHARPIN regulates platelet spreading on fibrinogen

Upon vascular injury, initial contacts may occur between resting platelets and matrix proteins von Willebrand factor and collagen under hemodynamic shear stress conditions. However, stable platelet attachment, spreading, and full aggregation require agonist-dependent activation of αIIbβ3, fibrinogen binding, and outside-in signaling through αIIbβ3.30 Because SHARPIN is a negative regulator of αIIbβ3 activation in human megakaryocytes derived from iPS cells,7 we examined whether its deletion impacts spreading of murine platelets adherent to fibrinogen. Indeed, in the absence of exogenous platelet agonists, SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ platelets spread more and attained a significantly greater average area and perimeter compared with SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− platelets (Figure 1A-D). Furthermore, SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ platelets extended longer, branched filopodia (Figure 1B and G-H). Similar results were obtained using platelets from SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre mice (supplemental Figure 3). Feedback mechanisms through endogenous platelet ADP and signaling cascades downstream of P2Y receptors can promote spreading of fibrinogen-adherent platelets.31-34 In fact, preincubation of the murine platelets with apyrase to degrade ADP or wortmannin to inhibit PI 3-kinase reduced the average area and perimeter of SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ platelets to levels observed in SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− platelets (Figure 1E-F). However, platelet stimulation with the PAR4 receptor agonist peptide induced a further increase in platelet area that was not significantly different between Cre+ and Cre− platelets (Figure 1I-K). These results indicate that deletion of SHARPIN from platelets leads to enhanced platelet spreading and filopodial extension on fibrinogen in a manner dependent on platelet ADP and PI 3-kinase.

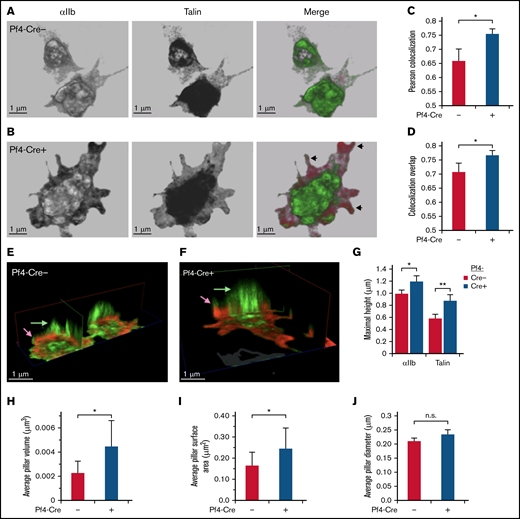

In pull-down studies, Rantala et al8 concluded that SHARPIN binding to the cytoplasmic tails of several integrin α subunits blocks interaction of talin and kindlin-3 with the integrin β1 cytoplasmic tail. To determine if deletion of SHARPIN would affect the colocalization of talin with αIIbβ3 in platelets, this process was examined by 3-dimensional (3D) stimulated emission depletion (STED) super-resolution microscopy (Figure 2A-B and E-F), which provides an XY resolution of <50 nm. In SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ knockout platelets, Pearson’s correlation coefficient and overlap coefficients indicated enhanced colocalization of talin with αIIbβ3 that was most evident at cell edges and filopodia (Figure 2C-D). 3D clippings of cell images depicted central cytoplasmic αIIbβ3-stained regions resembling apical-dorsal “pillars,” which extended from membrane-matrix contact zones and were a secondary region of enhanced talin-αIIbβ3 association in SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ knockout platelets (Figure 2E-F). Integrin αIIbβ3 pillars in SHARPIN knockout platelets also attained larger average pillar volumes and surface areas than their SHARPIN replete counterparts (Figure 2G-J). These results indicate that the loss of SHARPIN from platelets affects the 3D spatial distribution and association of αIIb and talin.

STED super-resolution microscopy 3D imaging of talin and αIIb localization in platelets. (A-J) SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ and SHARPINfl/fl Cre− platelets were allowed to spread on fibrinogen-coated coverslips for 30 minutes and then stained with primary antibodies against αIIb and talin and secondary Alexa-594 goat anti-rat and Atto 647N goat anti-mouse antibodies, respectively. Sixteen 0.1-μm sections that spanned the entire platelet were acquired with a Leica SP8 confocal STED microscope with white light laser, equipped with a ×100 STED oil objective. Images were processed using Leica LASX software and Photoshop, with linear adjustments applied similarly. (A-B) Front view of sample platelets from SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− (A) and SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ (B) mice. Arrowheads indicate peripheral regions of αIIb and talin association, pseudocolored green and red, respectively. (C-D) Quantification of αIIb and talin association, as indicated by Pearson’s colocalization (C) and colocalization overlap analyses (D). (E-F) Clipping views of SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− (E) and SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ (F) fibrinogen-adherent platelets showing central apical-dorsal “pillars” of αIIb and talin that traversed the platelet body and appeared as an organized assembly in 3D space. Arrows denote relative maximum heights of αIIb and talin. (G-J) Quantification of apical-dorsal pillars. Platelet αIIb staining was used to set a stringent threshold for pillar discrimination and applied identically to images of SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl Cre+ platelets. (G) Maximal pillar height. **P < .01. (H) Average pillar volume. (I) Average pillar surface area. (J) Average pillar diameter. SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− platelets showed significantly higher pillar volume and surface area than their wild-type counterparts (H-I), but no difference in column diameter was found (J). Approximately 25 to 40 cells were analyzed for each group. Data represent the sum of 4 individual experiments. n.s., not significant; *P < .05.

STED super-resolution microscopy 3D imaging of talin and αIIb localization in platelets. (A-J) SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ and SHARPINfl/fl Cre− platelets were allowed to spread on fibrinogen-coated coverslips for 30 minutes and then stained with primary antibodies against αIIb and talin and secondary Alexa-594 goat anti-rat and Atto 647N goat anti-mouse antibodies, respectively. Sixteen 0.1-μm sections that spanned the entire platelet were acquired with a Leica SP8 confocal STED microscope with white light laser, equipped with a ×100 STED oil objective. Images were processed using Leica LASX software and Photoshop, with linear adjustments applied similarly. (A-B) Front view of sample platelets from SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− (A) and SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ (B) mice. Arrowheads indicate peripheral regions of αIIb and talin association, pseudocolored green and red, respectively. (C-D) Quantification of αIIb and talin association, as indicated by Pearson’s colocalization (C) and colocalization overlap analyses (D). (E-F) Clipping views of SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− (E) and SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ (F) fibrinogen-adherent platelets showing central apical-dorsal “pillars” of αIIb and talin that traversed the platelet body and appeared as an organized assembly in 3D space. Arrows denote relative maximum heights of αIIb and talin. (G-J) Quantification of apical-dorsal pillars. Platelet αIIb staining was used to set a stringent threshold for pillar discrimination and applied identically to images of SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl Cre+ platelets. (G) Maximal pillar height. **P < .01. (H) Average pillar volume. (I) Average pillar surface area. (J) Average pillar diameter. SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− platelets showed significantly higher pillar volume and surface area than their wild-type counterparts (H-I), but no difference in column diameter was found (J). Approximately 25 to 40 cells were analyzed for each group. Data represent the sum of 4 individual experiments. n.s., not significant; *P < .05.

Platelet SHARPIN regulates αIIbβ3 activation

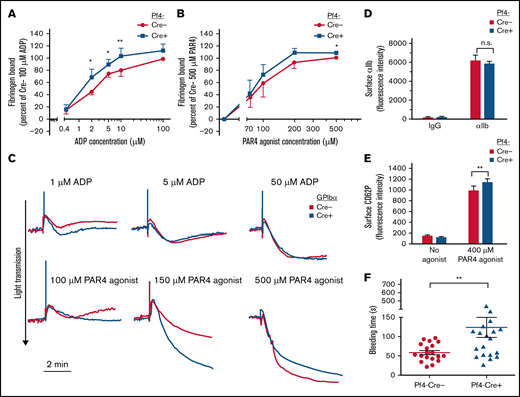

To determine whether the loss of platelet SHARPIN affects the process of αIIbβ3 activation, fibrinogen binding to platelets was studied in response to ADP or PAR4 agonist peptide. Unlike what we had previously observed in SHARPIN knockdown human iPS cell-derived megakaryocytes or platelets in vitro,7 no increase in basal fibrinogen binding to unstimulated platelets was observed in SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ knockout platelets (Figure 3A-B). However, both SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ (Figure 3A) and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ (supplemental Figure 4A) knockout platelets bound significantly more fibrinogen in response to submaximal ADP concentrations when compared with littermate control platelets (P < .05), and they showed increased fibrinogen binding in the presence of PAR4 agonist peptide (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 4B). Furthermore, light transmission aggregometry showed slightly enhanced aggregation by SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ platelets in response to submaximal concentrations of ADP and PAR4 agonist peptide (Figure 3C). No difference in integrin surface expression was observed between the platelet strains (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 4C). Stimulation with the peptide also produced a small but consistent increase in surface P-selectin expression in SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ compared with SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− platelets (Figure 3E; P < .01). These results suggest that SHARPIN-null platelets are somewhat more responsive to signals promoting integrin αIIbβ3-dependent spreading and activation than their wild-type counterparts. Because αIIbβ3 appeared to be primed to activation in vitro in the absence of SHARPIN, we wondered if this would translate to a shortening of the tail bleeding time in vivo. Contrary to this expectation, we observed instead a mild but consistent prolongation of tail bleeding times in SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ mice (Figure 3F) although no spontaneous bleeding was observed. Mouse tail bleeding times and hemostasis depend on multiple factors in addition to αIIbβ3-mediated platelet aggregation, including initial platelet adhesion to subendothelial matrix proteins including collagen, the latter through interactions largely with platelet GP VI, the primary platelet signaling receptor for collagen, and α2β1.35,36 Therefore, we examined platelet adhesion and thrombus growth under controlled shear flow conditions.

Effects of platelet SHARPIN deletion on platelet fibrinogen binding, aggregation, and tail bleeding times. (A-B) Flow cytometry of fibrinogen binding to agonist-stimulated platelets. Washed platelets were prepared from blood drawn from SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ mice and incubated for 30 minutes with Alexa-647–conjugated fibrinogen and indicated concentrations of platelet agonists (A) ADP or (B) PAR4 agonist peptide. Results are expressed as specific fibrinogen binding, as described in Methods. Data are from 5 experiments with ADP and 4 with PAR4 agonist peptide. Asterisks indicate statistical significance determined by Student t tests comparing fibrinogen bound at specific concentrations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis comparing bound fibrinogen at all input PAR4 concentrations attained statistical significance (*P < .05). (C) Representative platelet aggregation tracings from light transmission platelet aggregometry. SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre mouse platelet-rich plasma was diluted 1:2 with Walsh buffer in a glass cuvette warmed to 37°C in a Chronolog aggregometer (Havertown, PA), and the platelets were stimulated with the agonists indicated. Results are representative of at least 3 experiments. (D) αIIb surface expression was determined on platelets prepared (as in A-B) and compared with nonspecific IgG binding (n = 8), n.s., not significant. (E) FITC anti-CD62P binding to unstimulated or PAR 4 agonist peptide-stimulated platelets (n = 3). *P < .05; **P < .01). (F) Tail bleeding times were performed as described in Methods. Data represent results from SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− mice (n = 19) and SHARPINfl/fl Cre+ mice (n = 21). The time to arrest of bleeding is shown. **P = .01.

Effects of platelet SHARPIN deletion on platelet fibrinogen binding, aggregation, and tail bleeding times. (A-B) Flow cytometry of fibrinogen binding to agonist-stimulated platelets. Washed platelets were prepared from blood drawn from SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre+ mice and incubated for 30 minutes with Alexa-647–conjugated fibrinogen and indicated concentrations of platelet agonists (A) ADP or (B) PAR4 agonist peptide. Results are expressed as specific fibrinogen binding, as described in Methods. Data are from 5 experiments with ADP and 4 with PAR4 agonist peptide. Asterisks indicate statistical significance determined by Student t tests comparing fibrinogen bound at specific concentrations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis comparing bound fibrinogen at all input PAR4 concentrations attained statistical significance (*P < .05). (C) Representative platelet aggregation tracings from light transmission platelet aggregometry. SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre mouse platelet-rich plasma was diluted 1:2 with Walsh buffer in a glass cuvette warmed to 37°C in a Chronolog aggregometer (Havertown, PA), and the platelets were stimulated with the agonists indicated. Results are representative of at least 3 experiments. (D) αIIb surface expression was determined on platelets prepared (as in A-B) and compared with nonspecific IgG binding (n = 8), n.s., not significant. (E) FITC anti-CD62P binding to unstimulated or PAR 4 agonist peptide-stimulated platelets (n = 3). *P < .05; **P < .01). (F) Tail bleeding times were performed as described in Methods. Data represent results from SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre− mice (n = 19) and SHARPINfl/fl Cre+ mice (n = 21). The time to arrest of bleeding is shown. **P = .01.

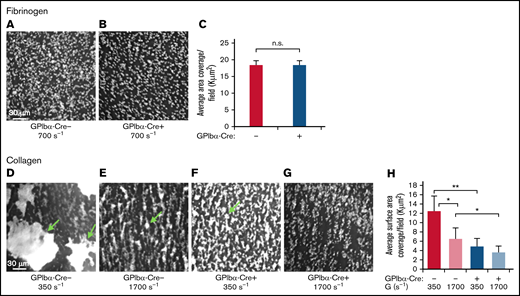

Loss of SHARPIN from platelets results in compromised thrombus formation on collagen under shear flow conditions. A predetermined volume of whole blood (130-200 μL) obtained from SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− (A,D,E) and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ (B,F,G) mice was aspirated through matrix-coated iBidi μSlide VI0.1 flow channels at the indicated shear rates. Adherent platelets were perfusion fixed and stained for αΙΙb, and images were acquired by deconvolution microscopy using a ×20 objective. The average platelet surface coverage was determined with Image Pro software (Media Cybernetics). (A-C) Fibrinogen matrix. n.s., not significant. (A-B) Deconvolved images of SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− (A) and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ attached platelets (B). (C) Average 2-dimensional area per field of view of fluorescent platelets attached to fibrinogen (n = 5). (D-H) Collagen matrix. *P < .05; **P< .01. (D-G) Images of attached platelets and thrombi. Arrows indicate platelet aggregates. (D,F) G = 350 s−1. (E,G) G = 1700 s−1. (H) Six optical sections of 0.2 μm each were acquired, and 3D rendered images of platelets and thrombi were prepared. The average 3D surface area per field of view of fluorescent platelets on collagen was calculated using Image-Pro software (n = 5).

Loss of SHARPIN from platelets results in compromised thrombus formation on collagen under shear flow conditions. A predetermined volume of whole blood (130-200 μL) obtained from SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− (A,D,E) and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ (B,F,G) mice was aspirated through matrix-coated iBidi μSlide VI0.1 flow channels at the indicated shear rates. Adherent platelets were perfusion fixed and stained for αΙΙb, and images were acquired by deconvolution microscopy using a ×20 objective. The average platelet surface coverage was determined with Image Pro software (Media Cybernetics). (A-C) Fibrinogen matrix. n.s., not significant. (A-B) Deconvolved images of SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− (A) and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ attached platelets (B). (C) Average 2-dimensional area per field of view of fluorescent platelets attached to fibrinogen (n = 5). (D-H) Collagen matrix. *P < .05; **P< .01. (D-G) Images of attached platelets and thrombi. Arrows indicate platelet aggregates. (D,F) G = 350 s−1. (E,G) G = 1700 s−1. (H) Six optical sections of 0.2 μm each were acquired, and 3D rendered images of platelets and thrombi were prepared. The average 3D surface area per field of view of fluorescent platelets on collagen was calculated using Image-Pro software (n = 5).

Platelet SHARPIN regulates platelet thrombus growth on collagen under shear flow conditions

Mice lacking functionality of both GP VI and α2β1 suffer moderate bleeding defects.35,36 To test SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre platelet-matrix interactions under hemodynamic shear stress conditions, we aspirated whole blood through iBidi flow chamber channels coated with fibrinogen at shear rate, G = 700 s−1, or collagen at G = 350 s−1 or 1700 s−1. These low and high shear rates mimic venous and arterial flow conditions, respectively. At high shear rates, von Willebrand factor is also required for initial tethering via GP Ib-V-IX,37 and it precedes engagement with collagen through GPVI and α2β1.35 Platelets attached to the coated matrix were perfusion-fixed and stained for αIIb. On fibrinogen, platelet adhesion as assessed by surface area coverage was similar with platelets from SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ mice (Figure 4A-C). In sharp contrast, the surface area coverage on collagen by SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ platelets was compromised, with coverage decreased by 61% and 45% at G = 350 s−1 and 1700 s−1, respectively (Figure 4D-H). This result appeared to be due to a decreased ability of SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ platelets to form thrombi relative to their wild-type counterparts. Thus, the loss of SHARPIN severely hampers thrombus growth on collagen at high and low shear rates, likely through pathways downstream of GPVI and α2β1 collagen receptors.

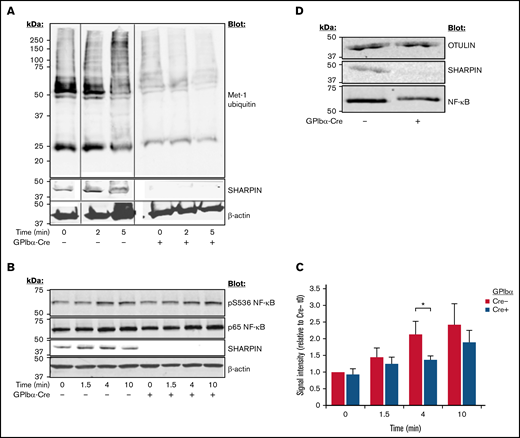

Platelet SHARPIN promotes inflammatory responses in mice

Cpdm mice with global SHARPIN deletion exhibit multiorgan inflammation and severe dermatitis, which can be partially alleviated with β1-integrin inhibition in vivo38 but is primarily driven by LUBAC destabilization, reduced NF-κB activation, and diminished protection against tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α–induced apoptosis.39 To examine LUBAC function in platelets, we performed western blots with lysate from platelets stimulated with a cocktail of agonists. In contrast to a time-dependent increase in Met-1 ubiquitination observed upon agonist stimulation of SHARPIN-replete platelets, SHARPIN-null platelets exhibited substantially lower levels of Met-1 ubiquitination, both before and after agonist stimulation (Figure 5A). Similarly, phosphorylation of serine 536 of the p65/RelA NF-κB subunit, known to be correlated with its activation,40 was decreased in SHARPIN-null platelets (Figure 5B-C). OTULIN, which specifically and uniquely deubiquitinates linear ubiquitin linkages, was expressed at similar levels in SHARPIN-depleted and -replete platelets (Figure 5D), indicating that differences in Met-1 ubiquitination and NF-κB phosphorylation were due to the loss of LUBAC function in the absence of SHARPIN.

Platelet-specific deletion of SHARPIN curtails Met-1 ubiquitination and reduces NF-κB pathway signaling. Western blots of SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre or SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre mouse platelets following stimulation with an agonist cocktail of 400 μM of PAR4 agonist peptide, 50 μM of ADP, and 50 μM of epinephrine, lysed at the indicated times, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and blotted for Met-1 ubiquitin (n = 3) (A) and phosphoserine 536 (B) of the p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-κB. (C) Summary of signal intensity of pS536 NF-κB (n = 5; *P < .05). β-actin re-probes were used as loading controls. (D) Western blot of OTULIN indicating similar levels in SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+platelet lysate (n = 3).

Platelet-specific deletion of SHARPIN curtails Met-1 ubiquitination and reduces NF-κB pathway signaling. Western blots of SHARPINfl/fl Pf4-Cre or SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre mouse platelets following stimulation with an agonist cocktail of 400 μM of PAR4 agonist peptide, 50 μM of ADP, and 50 μM of epinephrine, lysed at the indicated times, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and blotted for Met-1 ubiquitin (n = 3) (A) and phosphoserine 536 (B) of the p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-κB. (C) Summary of signal intensity of pS536 NF-κB (n = 5; *P < .05). β-actin re-probes were used as loading controls. (D) Western blot of OTULIN indicating similar levels in SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+platelet lysate (n = 3).

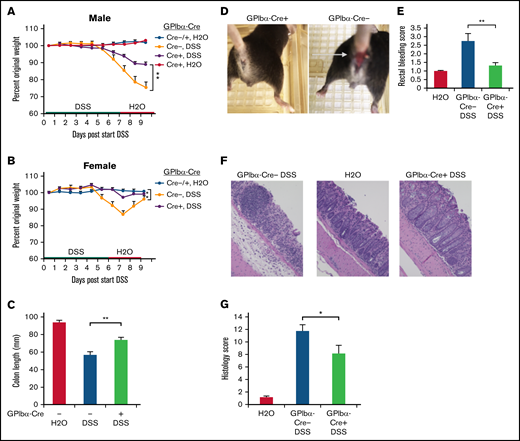

Excessive or unattenuated immune responses to harmful environmental triggers or pathogens may result in unchecked inflammation. Inflammatory bowel disease is characterized by erosion of normal epithelial barriers, compromised mucosal integrity, and leukocyte invasion into the affected tissue.41 In patients, this may manifest as bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss.42,43 Because platelets may contribute to acute colitis in humans and in experimental mouse colitis models,42,44 we asked whether SHARPIN loss from platelets would affect colitis development in mice. For in vivo inflammation studies, GPIbα-Cre mice were used to avoid complications of a potential leaked expression of Pf4-Cre in myeloid cells. SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre age- and sex-matched littermate mice were challenged with DSS in an established model of murine colitis. When studied over a period of several days, this model involved primarily recruitment of neutrophils to the inflamed bowel. GPIbα-Cre+ and Cre− mice were treated with 2.4% DSS, followed by water only, as indicated in Figure 6A-B. Control mice had water only throughout the study, and all mice were euthanized on day 9. Weight loss (Figure 6A-B), colon shrinkage (Figure 6C), and incidence of rectal bleeding (Figure 6D-E) were markedly reduced in SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ knockout mice compared with SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− mice, and the former mice appeared less lethargic. Histological evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin–stained colon sections indicated that SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− mice exhibited a complete loss of crypts and surface epithelium; they also showed mucosa heavily infiltrated with inflammatory cells and enlarged lymphoid follicles and submucosa with marked edema and modest inflammation. In contrast, SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ mice had fewer epithelial focal ulcerations with minimal extension to submucosal layers, an intact epithelium, and more restricted leukocyte infiltration (Figure 6F). This resulted in a lower histological disease score in the platelet-specific SHARPIN knockout mice (Figure 6G). Unfloxed SHARPINWTGPIbα-Cre+ mice showed a disease profile similar to that of the SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− mice (supplemental Figure 5), an important control indicating that platelet expression of Cre alone is not protective against DSS-induced colitis.

Platelet-specific deletion of SHARPIN ameliorates DSS-induced colitis. (A-G) SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre mice were provided autoclaved water or DSS, and then all mice were switched to water only, as indicated, and euthanized on day 9. (A-B) Mouse weight loss, represented as a percentage of original weight, for males (A) and females (B) (n = 8, n = 4, respectively) (**P < .01 by 2-way ANOVA analysis) (C) Colon length (n = 12/11, combined male and female mice). (Note: 1 SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− mouse died before the end of the experiment, leading to colon autolysis, yielding unequal n.) (D) Rectal bleeding in SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ (left) and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− (right) mice, as indicated by the arrow. (E) Summary of rectal bleeding score (n = 9) (right). (F) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of paraffin-embedded SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre tissue imaged at ×20 from the medial-distal region of the colon, showing extensive inflammation and ulceration in the SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− colons. (G) Histology score calculated from H&E-stained colon images (n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Platelet-specific deletion of SHARPIN ameliorates DSS-induced colitis. (A-G) SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre mice were provided autoclaved water or DSS, and then all mice were switched to water only, as indicated, and euthanized on day 9. (A-B) Mouse weight loss, represented as a percentage of original weight, for males (A) and females (B) (n = 8, n = 4, respectively) (**P < .01 by 2-way ANOVA analysis) (C) Colon length (n = 12/11, combined male and female mice). (Note: 1 SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− mouse died before the end of the experiment, leading to colon autolysis, yielding unequal n.) (D) Rectal bleeding in SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ (left) and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− (right) mice, as indicated by the arrow. (E) Summary of rectal bleeding score (n = 9) (right). (F) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of paraffin-embedded SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre tissue imaged at ×20 from the medial-distal region of the colon, showing extensive inflammation and ulceration in the SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− colons. (G) Histology score calculated from H&E-stained colon images (n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

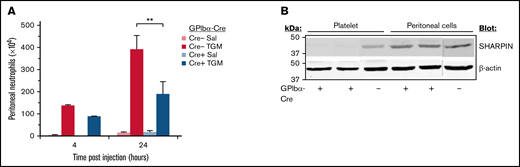

Inflammation of the abdominal peritoneum may be driven by microbial infection or may be a secondary consequence of other medical conditions. Therefore, a peritonitis model of sterile inflammation upon addition of thioglycollate medium was implemented to test whether SHARPIN-deficient mouse platelets can promote neutrophil recruitment to the peritoneum, as reported for wild-type platelets.43-47 Mice were injected intraperitoneally with thioglycollate medium or saline, and neutrophil influx into the peritoneum was determined after 4 and 24 hours, time points largely preceding influx of other leukocytes. After treatment with thioglycollate medium, SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− mice both recruited neutrophil populations enriched in bands. However, SHARPINfl/fl Cre+ mice recruited 50% fewer neutrophils at 24 hours than their GPIbα-Cre− littermate counterparts (Figure 7A; P < .01). This difference was not due to decreased SHARPIN expression in recruited leukocytes, as western blots demonstrated that SHARPIN expression was maintained in Cre− and Cre+ cells obtained from the peritoneal fluid (Figure 7B). Thus, SHARPIN in mouse platelets not only plays a role in regulating integrin function but also participates in inflammatory response pathways that involve platelets.

Platelet-specific deletion of SHARPIN reduces neutrophil recruitment in a peritonitis model of sterile inflammation. (A) SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ mice were injected with thioglycollate medium or saline and euthanized at 4 or 24 hours, and peritoneal lavage fluid was harvested. The number of neutrophils was determined as described in Methods (n = 5; **P < .01). (B) Western blot of lysate from SHARPINfl/GPIbα-Cre− or SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ mouse platelets or from harvested peritoneal lavage fluid, subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted for SHARPIN. β-actin re-probes were used as a loading control. The blots are representative of results obtained with lysate from 3 mice each.

Platelet-specific deletion of SHARPIN reduces neutrophil recruitment in a peritonitis model of sterile inflammation. (A) SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre− and SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ mice were injected with thioglycollate medium or saline and euthanized at 4 or 24 hours, and peritoneal lavage fluid was harvested. The number of neutrophils was determined as described in Methods (n = 5; **P < .01). (B) Western blot of lysate from SHARPINfl/GPIbα-Cre− or SHARPINfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ mouse platelets or from harvested peritoneal lavage fluid, subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted for SHARPIN. β-actin re-probes were used as a loading control. The blots are representative of results obtained with lysate from 3 mice each.

Discussion

In the present study, we used two independent megakaryocyte lineage-specific Cre mouse strains with the goal of assessing the specific function of SHARPIN in platelets.20,21 It demonstrates that SHARPIN contributes to both the inflammatory and αIIbβ3-mediated adhesive functions of platelets. First, the results establish a restraining role for SHARPIN in the affinity regulation of αIIbβ3 in mouse platelets, expanding on previous observations in SHARPIN-knockdown platelets and megakaryocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells.7 Specifically, SHARPIN-null platelets exhibited increased binding of soluble fibrinogen to αIIbβ3, greater ADP-dependent platelet spreading on immobilized fibrinogen, and increased 3D colocalization of αIIbβ3 and talin, as revealed by 3D super-resolution microscopy, but reduced thrombus formation on collagen. Second, the results establish a role for platelet SHARPIN in regulating platelet contributions to inflammation, an increasingly recognized function of these cells.48,49 Specifically, SHARPIN-null platelets exhibited a reduction in LUBAC-mediated Met-1 ubiquitination of platelet proteins and NF-κB activation. Extrapolating from studies with human iPS cell-derived megakaryocytes,7 some of these Met-1 polyubiquinated proteins in platelets are likely involved in the inflammatory response, possibly through NF-κB signaling and through other as-yet unidentified signaling pathways. Accordingly, mice lacking platelet SHARPIN demonstrated significantly reduced responses in vivo in 2 models of inflammation that are reported to be platelet-dependent: DSS-induced colitis and sterile peritonitis,42,43,47 which is striking considering the previously reported systemic inflammation in mice lacking Sharpin globally.17,18 Altogether, these results reveal SHARPIN’s dual roles in integrin and LUBAC signaling in platelets.

The present results are consistent with a role for platelet SHARPIN as a negative regulator of αIIbβ3 activation and cytoskeletal reorganization, at least in vitro, particularly under conditions of submaximal platelet stimulation by ADP that may result from sporadic binding of fibrinogen to platelets causing downstream “outside-in” signaling and release of dense granule ADP.33 Rantala et al8 showed that interaction of SHARPIN with the integrin α5 cytoplasmic tail inhibited talin and kindlin binding to the corresponding integrin β1 tails in cells. Consistent with those observations, we found an increase in talin colocalization with αIIbβ3 in SHARPIN-null platelets by 3D super-resolution microscopy, likely due to enhanced talin access to the β3 cytoplasmic tail. There are several other αIIb tail-binding proteins in platelets that may also serve to positively or negatively regulate αIIbβ3 affinity/avidity for fibrinogen.50-52 Future studies may be able to determine the role of these other αIIb tail-binding proteins in platelets relative to that of SHARPIN as well as the role, if any, of LUBAC-mediated Met-1 ubiquitination in αIIbβ3 expression or function. The diminished attachment and thrombus growth on collagen of SHARPIN-deficient platelets potentially implicates SHARPIN in platelet activation through collagen receptors. Previously, a defect in spreading and accelerated force-induced detachment from collagen-coated beads of SHARPIN-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts was described,53 and future studies of SHARPIN-deficient platelets should help to clarify precisely how SHARPIN impacts collagen receptor signaling.

The Sharpinfl/fl Cre+ mice we generated have platelet-specific deletion of SHARPIN and reduced levels of HOIP expression and LUBAC function, similar to that observed in other cells from cpdm global SHARPIN-null mice.17,18 However, unlike cpdm mice, our platelet-specific SHARPIN knockout mice exhibited no overt signs of spontaneous dermatitis or organ inflammation. This may be expected because the dermatitis is largely driven by TNF-α–mediated apoptosis in keratinocytes,54,55 whereas T and B cells largely contribute to multiorgan inflammation.56 Nevertheless, SHARPIN deletion from platelets reduced inflammatory disease outcome in mice. Sharpinfl/fl GPIbα-Cre+ mice were relatively protected from DSS-induced colitis based on assessment of weight loss, colon shortening, gross rectal bleeding, and colon histology. Similarly, in a sterile peritonitis model, mice lacking platelet SHARPIN showed reduced neutrophil infiltration. These results imply that platelet SHARPIN may normally participate in certain inflammatory responses in vivo, indicating an action that is distinct from its anti-apoptotic role in keratinocytes. Apart from SHARPIN’s destabilization of LUBAC and decreased Met-1 ubiquitination, the lower platelet HOIP levels may have consequences for inflammation. Previous reports on platelet contributions to inflammation in in vivo model systems have identified molecular interactions at the cell surface, including leukocyte PSGL-1/platelet P-selectin binding, exocytosis of platelet storage granule contents, and microparticle shedding as possible mechanisms.43,44 While it remains to be determined precisely how SHARPIN in platelets contributes to the inflammatory response in colitis and peritonitis models, our data provide an unambiguous demonstration of the role of platelets in inflammation.

The LUBAC complex has been most widely studied in leukocytes in which its role in Met-1 ubiquitination of NEMO and NF-κB activation is a premier example of LUBAC function. The NF-κB axis is a central player in inflammation, with optimal levels of NF-κB activation maintained by a diverse set of activation intermediates, ubiquitinases, and deubiquitinases.57 The cell-dependent outcome of inhibiting NF-κB pathway members is reflected by the protective effect of NF-κB inhibition in a DSS model of colitis,58 in contrast to the full-blown spontaneous colitis induced by loss of NEMO in the gut endothelium.59 Given the importance of Met-1 ubiquitination in classic NF-κB activation12 and NF-κB’s role in promoting transcription of inflammatory cytokines, it is tempting to speculate that platelet SHARPIN modulates inflammatory responses by Met-1 ubiquitination of proteins within the platelet NF-κB axis. Recent studies have outlined nongenomic functions of NF-κB or its activation intermediates in aspects of platelet activation,60 and as in other cells, Met-1 polyubiquitination may affect proteins unrelated to NF-κB.61 Further work is required to tease out precise mechanisms whereby Met-1 ubiquitination regulates the inflammatory responses of platelets.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Kelley and Marissa Matsumoto (Genentech) for the gift of the 1F11 anti-Met1 ubiquitin antibody, Yotis Senis (Université de Strasbourg) for information on how to obtain GPIbα-Cre mice, Zaverio Ruggeri (Scripps Research Institute) for access to a platelet aggregometer, and Lars Eckmann (UCSD Gastroenterology) for assistance in interpretation of colon histology. Turku Center for Disease Modeling and Biocenter Finland are acknowledged for services, instrumentation, and expertise.

This work was supported by the National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute, National Institutes of Health (grants HL56595, HL78784, and HL151433) and by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health (grants NS047101 and P30 2P30CA023100-28) (USCD Microscopy Core).

Authorship

Contribution: A.K.-F. conceived of, designed, and performed experiments and wrote the paper; S.J.S. conceived of and designed experiments and wrote the paper; E.P. and J.I. previously established that SHARPIN is an integrin-regulatory protein relevant to cancer cells, provided the SHARPINfl/fl mice, and edited the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ana Kasirer-Friede, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Dr, La Jolla, CA 92093-0726; e-mail: akasirerfrede@health.ucsd.edu.

References

Author notes

Requests for data sharing may be submitted to Ana Kasirer-Friede (akasirerfriede@health.ucsd.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.