Key Points

Increased levels of interleukin 1 were found in the bone marrow fluid of TpoTg mice, whereas levels were lowered in Mpl−/− mice.

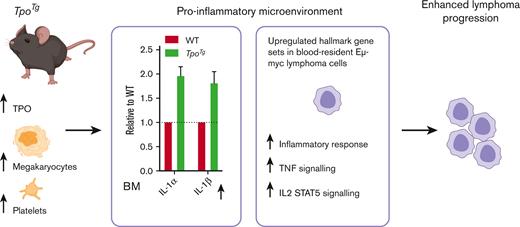

A proinflammatory microenvironment promoted Eμ-myc lymphoma progression in TpoTg mice with high megakaryocyte and thrombopoietin levels.

Abstract

Platelets have been shown to enhance the survival of lymphoma cell lines. However, it remains unclear whether they play a role in lymphoma. Here, we investigated the potential role of platelets and/or megakaryocytes in the progression of Eμ-myc lymphoma. Eμ-myc tumor cells were transplanted into recipient wild-type (WT) control, Mpl−/−, or TpoTg mice, which exhibited normal, low, and high platelet and megakaryocyte counts, respectively. TpoTg mice that underwent transplantation exhibited enhanced lymphoma progression with increased white blood cell (WBC) counts, spleen and lymph node weights, and enhanced liver infiltration when compared with WT mice. Conversely, tumor-bearing Mpl−/− mice had reduced WBC counts, lymph node weights, and less liver infiltration than WT mice. Using an Mpl-deficient thrombocytopenic immunocompromised mouse model, our results were confirmed using the human non-Hodgkin lymphoma GRANTA cell line. Although we found that platelets and platelet-released molecules supported Eμ-myc tumor cell survival in vitro, pharmacological inhibition of platelet function or anticoagulation in WT mice transplanted with Eμ-myc did not improve disease outcome. Furthermore, transient platelet depletion or sustained Bcl-xL–dependent thrombocytopenia did not alter lymphoma progression. Cytokine analysis of the bone marrow fluid microenvironment revealed increased levels of the proinflammatory molecule interleukin 1 in TpoTg mice, whereas these levels were lower in Mpl−/− mice. Moreover, RNA sequencing of blood-resident Eμ-myc lymphoma cells from TpoTg and WT mice after tumor transplantation revealed the upregulation of hallmark gene sets associated with an inflammatory response in TpoTg mice. We propose that the proinflammatory microenvironment in TpoTg mice promotes lymphoma progression.

Introduction

The interaction between tumor cells and their microenvironment is known to play a key role in tumor malignancy.1 The tumor microenvironment comprises different cell types and noncellular compartments including stroma and the different effectors of the immune system.2 Platelets and their precursor cells, the megakaryocytes, also contribute to the tumor microenvironment.3 Platelets are tiny blood cells with important roles in hemostasis and thrombosis that are quickly activated in response to an injury. They are produced by megakaryocytes residing in the bone marrow (BM), spleen, and lungs. Thrombopoietin (TPO) is the master cytokine regulator of megakaryopoiesis.4 TPO maintains hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis and regulation of megakaryocyte and platelet number.5

In mouse models of solid tumors, platelets have been shown to promote blood-borne metastasis6-8 and safeguard the tumor vasculature.9 Moreover, a correlation between increased platelet counts and shorter patient survival times has been described for several solid tumors.7,10-12 Both pharmacological inhibition of platelet function and transient platelet depletion significantly reduced metastasis in murine models.6 In humans, long-term retrospective analyses of cancer incidence demonstrated reduced prevalence13 and death from multiple solid cancer types in patients taking daily low-dose aspirin,14 although this was not the case in older individuals.15 Daily aspirin did not reduce death in hematologic malignancy,14 and there are conflicting results on the association between aspirin intake and the risk of acquiring lymphoma. Qiao et al13 and Amoori et al16 performed a meta-analysis of observational studies and found no association between aspirin intake and the risk of lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), respectively. However, a recent study by Liebow et al17 reported that low-dose aspirin, but not regular/extra strength aspirin or other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, was associated with a lower risk of NHL.

Lymphoma is the most common form of blood cancer in high-income countries. NHL accounts for 90% of lymphoma cases, of which, 80% originate from B-lymphoid cells. Lymphoma is listed among the neoplasias with a high risk of venous thromboembolism,18 with an incidence ranging from <5% to 59.5%.19 The incidence is higher in NHL than it is in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).19

A recent study in mice reported that platelets can serve as drug carriers to deliver chemotherapy for the treatment of lymphoma,20 stressing the close interaction between platelets and lymphoma cells. Although limited information is available on the role of platelets in lymphoma and leukemia, studies that have investigated the interactions between activated platelets or platelet-released molecules (PRMs) and lymphoma, leukemia, and myeloma cell lines have shown that platelets provide protection from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis and enhance tumor cell survival in vitro.21,22 Another study revealed that thrombin activated platelets adhered to lymphoma cells following coincubation and caused lymphoma cell release of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α).23 Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that platelets enhanced multiple myeloma progression via interleukin 1β (IL-1β) upregulation.24 However, the role of platelets and/or megakaryocytes in lymphoma progression has not been investigated.

Here, we show that when Eμ-myc lymphoma cells were transplanted into TpoTg mice5 (overexpressing TPO in the liver) with high megakaryocyte and platelet counts, the mice exhibited enhanced lymphoma progression when compared with the wild-type (WT) mice. Conversely, tumor-bearing Mpl−/− mice25 (lacking the TPO receptor Mpl) with low megakaryocyte and platelet counts presented with reduced lymphoma progression when compared with the WT. Consistent with previous reports, platelets and PRMs supported Eμ-myc tumor cell survival in vitro; however, pharmacological inhibition of platelet activation or transient platelet depletion did not alter the disease outcome. Cytokine analysis of the BM fluid microenvironment revealed increased levels of the proinflammatory molecule IL-1 in TpoTg mice, whereas these levels were lower in Mpl−/− mice. Moreover, RNA sequencing of Eμ-myc lymphoma cells from TpoTg mice after tumor transplantation revealed upregulation of hallmark gene sets associated with an inflammatory response. Hence, our study suggests that the proinflammatory microenvironment in TpoTg mice promotes the progression of Eμ-myc lymphoma.

Methods

Mice

Eμ-myc,26Mpl−/−,25TpoTg,5Bcl-xPlt20/Plt20,27 and NSGMpl−/−7 mice have been previously described. The mice were aged 8 to 12 weeks, and the experiments included gender-balanced groups, if not otherwise stated. All strains were on C57BL/6 or NOD-SCIDIL2Rγ−/− (NSG) background. C57BL/6 albino28 and TpoTg C57BL/6 albino mice were used for live-imaging experiments. All animal procedures adhered to the National Health and Medical Research Council code of practice for the care and use of animals for experimental purposes in Australia and were approved by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute Animal Ethics Committee.

In vivo lymphoma transplantation

WT C57BL/6, Mpl−/−, TpoTg, NSG, and NSGMpl−/− mice were injected IV with 104 (passage 1 [P1] 166, 5849, and 5903) or 2 × 104 (immortalized 5849) Eμ-myc lymphoma cells. GRANTA cells (2 × 106) were injected intraperitoneally into NSG and NSGMpl−/− mice. The mice were euthanized and analyzed simultaneously once the first mouse in the experimental cohort reached the ethical end point. Disease severity was measured by blood counts, spleen and lymph node (axillary, brachial, inguinal, and mesenteric) weights, and the extent of lymphoma liver infiltration.

Cytokine analysis of BM fluid

For collecting BM fluids, the 2 femurs and 2 tibiae of each mouse were flushed with 200 μL of Hanks balanced salt solution/2% fetal bovine serum using a 0.3 mL insulin syringe with a 28-gauge needle and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 minutes to remove the BM cells. The supernatants were further clarified by centrifugation at 12 000 × g for 10 minutes, and samples were subsequently stored at −80°C until use.29 Cytokine levels were determined using the Proteome profiler array, mouse cytokine array panel A (R&D #ARY006) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each loaded sample was combined from 2 mice.

Data analysis

The statistical significance between 2 treatment groups was analyzed using an unpaired Student t test with 2-tailed P values. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparison test was applied where appropriate (GraphPad Prism 9). The values were ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, or as otherwise stated. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Detailed information about the materials used and the experimental procedures can be found in supplemental Methods.

Results

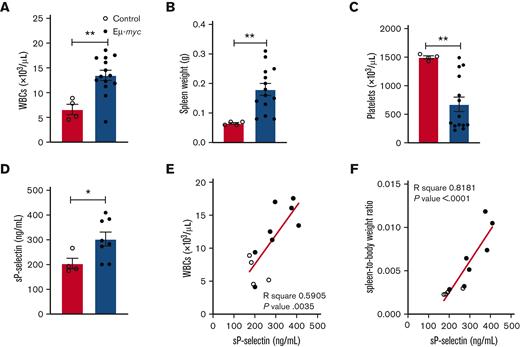

Platelets degranulate in mice with Eμ-myc lymphoma

The Eμ-myc transgenic mouse is a model of aggressive Burkitt lymphoma (an NHL subtype).26 The activation status of platelets in Eμ-myc tumor-bearing mice was determined by examining platelet degranulation in mice with Eμ-myc lymphoma and in control mice. C57BL/6 mice were injected IV with immortalized Eμ-myc cells and analyzed 3 weeks later when they showed signs of lymphoma. As expected, lymphoma-bearing mice had increased white blood cell (WBC) counts, enlarged spleens, and reduced platelet numbers (Figure 1A-C). The adhesion molecule, P-selectin, is mobilized to the platelet surface when platelet activation and degranulation are triggered. Subsequently, P-selectin rapidly sheds from the platelet surface.30 As a measure of platelet degranulation, we performed quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of soluble (s) P-selectin in serum. The level of sP-selectin in serum was significantly increased in mice with lymphoma, and sP-selectin exhibited a strong positive correlation with tumor burden (WBCs and spleen weight) (Figure 1D-F), indicating that platelets degranulate in mice with increasing tumor load. Because endothelial cells can also release sP-selectin, we cannot exclude the contribution of enhanced endothelial cell activation.

Increased sP-selectin levels in mice with lymphoma. (A) WBC count, (B) spleen weight, (C) platelet count, and (D) serum sP-selectin concentration in WT C57BL/6 mice 3 weeks after Eμ-myc 5849 IV transplantation (2 × 104 immortalized cells per mouse). Student unpaired t test. n = 4 untreated control mice; n = 8 to 14 mice transplanted with Eμ-myc. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Mean ± SEM, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005. (E) WBC count and (F) spleen/body weight ratio correlated with sP-selectin concentration in serum. Clear circles = control mice (n = 4). Black circles = mice transplanted with Eμ-myc (n = 8). Linear regression analysis. sP-selectin, soluble P-selectin.

Increased sP-selectin levels in mice with lymphoma. (A) WBC count, (B) spleen weight, (C) platelet count, and (D) serum sP-selectin concentration in WT C57BL/6 mice 3 weeks after Eμ-myc 5849 IV transplantation (2 × 104 immortalized cells per mouse). Student unpaired t test. n = 4 untreated control mice; n = 8 to 14 mice transplanted with Eμ-myc. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Mean ± SEM, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005. (E) WBC count and (F) spleen/body weight ratio correlated with sP-selectin concentration in serum. Clear circles = control mice (n = 4). Black circles = mice transplanted with Eμ-myc (n = 8). Linear regression analysis. sP-selectin, soluble P-selectin.

Platelets and PRMs promote Eμ-myc tumor cell survival

Next, we examined whether murine platelets influence the survival of immortalized Eμ-myc lymphoma cells in vitro when coincubated for 48 hours at 37°C and supplemented with 5% serum. Markedly, platelets augmented lymphoma cell survival in the 4 Eμ-myc cell lines tested (A118C, 5849, 1194, and AF40A, Figure 2A), an effect confirmed by A118C cells present at a range of serum concentrations (1%-10%) (supplemental Figure 1A). Next, we assessed whether PRMs affect Eμ-myc survival. PRMs were generated and concentrated following thrombin activation of WT murine platelets. Coincubation for 48 hours with PRMs enhanced the survival of 3 (A118C, 5849, and 1194) out of 4 Eμ-myc cell lines (Figure 2B). This effect was similar to that observed upon the addition of platelets when A118C and 1194 cells were used. This result indicated that PRMs alone can promote the survival of Eμ-myc lymphoma cells but not in all cell lines. Next, we explored the impact of incubation time. Platelet activation with subsequent degranulation is known to be a rapid process,31 and therefore, we investigated whether 48 hours of coincubation was needed. Platelet coincubation for 24 and 48 hours in 5% serum was compared, but only coincubation for 48 hours was shown to significantly increase Eμ-myc survival (supplemental Figure 1B). Platelet coincubation for 4 or 24 hours followed by 48 or 24 hours of incubation after washing, respectively, did not affect Eμ-myc survival (supplemental Figure 1B). Next, the Eμ-myc cells were serum starved for 24 hours before the addition of platelets. Platelets were then added for 4 hours, followed by incubation for 24 hours after washing but without any effect on survival. Nevertheless, 24 hours of platelet coincubation after starvation significantly increased survival to the same degree as 48 hours of platelet coincubation in the absence of serum starvation (supplemental Figure 1B). Thus, it appeared that a platelet coincubation time of <48 hours (24 hours but not 4 hours) was only efficient when the Eμ-myc cells were stressed by starvation. In summary, platelets and PRMs promoted Eμ-myc survival in vitro.

Platelets and PRMs promote survival of Eμ-myc cell lines. (A) Eμ-myc cell lines A118C, 5849, 1194, and AF40A were coincubated with murine platelets for 48 hours at 37°C and 5% serum, and percentage survival was assessed by flow cytometry. n = 4 to 12 per condition. (B) Eμ-myc cell lines were coincubated with murine platelets or PRMs for 48 hours at 37°C and 5% serum, and percentage survival was assessed by flow cytometry. A118C, n = 12 to 22; 5849, n = 21 to 54; 1194, n = 18; and AF40A, n = 12 to 15. Vehicle (n = 3 per cell line) includes thrombin. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Student unpaired t test, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant.

Platelets and PRMs promote survival of Eμ-myc cell lines. (A) Eμ-myc cell lines A118C, 5849, 1194, and AF40A were coincubated with murine platelets for 48 hours at 37°C and 5% serum, and percentage survival was assessed by flow cytometry. n = 4 to 12 per condition. (B) Eμ-myc cell lines were coincubated with murine platelets or PRMs for 48 hours at 37°C and 5% serum, and percentage survival was assessed by flow cytometry. A118C, n = 12 to 22; 5849, n = 21 to 54; 1194, n = 18; and AF40A, n = 12 to 15. Vehicle (n = 3 per cell line) includes thrombin. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Student unpaired t test, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant.

Increased lymphoma and leukemia progression in TpoTg mice

Given that platelets degranulate in Eμ-myc lymphoma and that platelets, and in some cases PRMs, enhance Eμ-myc survival in vitro, we investigated whether changes in platelet number would influence myc-driven lymphoma progression. To test this, we expanded spleen- and lymph node–derived Eμ-myc tumor cells from 3 Eμ-myc transgenic mice26 (166, 5903, and 5849) in WT C57BL/6 mice, recovered the cells, and then injected IV P1 cells into groups of recipient Mpl−/−,25 WT or TpoTg5 mice (which exhibit low, 109.8 × 103 cells per μL ± 12 × 103 cells per μL; normal, 1111 × 103 cells per μL ± 25 × 103 cells per μL, and high platelet counts of 3648 × 103 cells per μL ± 132 × 103 cells per μL, respectively, supplemental Figure 2A). Mice were analyzed simultaneously once the first mouse in the experimental cohort reached the ethical end point. Untreated adult Mpl−/− and TpoTg mice had normal lymphocyte and WBC numbers (supplemental Figure 2B-C) and spleen size.7,32,33 We first compared the WT and Mpl−/− recipients, where Eμ-myc lymphoma progression was reduced in thrombocytopenic Mpl−/− mice compared than in WT mice, based on reduced WBC and lymphocyte counts and a lower number of immature B cells in the spleen (Figure 3A-C). The spleen weights did not differ (Figure 3D). Next, we assessed lymphoma progression cocurrently in cohorts of WT, Mpl−/−, and TpoTg recipients at the time when the first TpoTg recipients became unwell. We found that both Eμ-myc 5903- and 5849-mediated lymphoma progression was augmented in TpoTg mice when compared to WT mice, based on higher WBC and lymphocyte counts, increased spleen weights, and total lymph node weights (Figure 3E-H). Platelet counts in TpoTg mice were reduced but were still more than those in WT mice that did not undergo transplantation (supplemental Figure 2A,D-E). Conversely, in thrombocytopenic Mpl−/− mice, a reduced tumor burden was evident compared with that in WT mice, most reflected in reduced WBC count and lymph node weight, albeit variably (Figure 3E,H), and spleen weight was not affected (Figure 3G). In late-stage Eμ-myc disease, the liver becomes infiltrated with lymphoma cells and therefore, we quantified lymphocyte liver infiltration in hematoxylin and eosin–stained liver sections. We found that sections from TpoTg mice had an increased area covered by tumor infiltrating cells compared with those from WT mice, an effect that was modestly reversed in Mpl−/− mice (Figure 3I). To further visualize the tumor burden, we transduced 5849 Eμ-myc tumor cells with a mCherry-luciferase retrovirus vector, and mCherry-luciferase positive cells were injected into albino WT and TpoTg mice. For visualization of tumor distribution, D-luciferin was injected 7 days after tumor transplantation, and the mice were imaged using the IVIS Spectrum in vivo imaging system to detect luciferase bioluminescence. Consistent with other measures, representative images indicated that TpoTg mice exhibited a greater tumor load than WT mice, which was visible in both the lymph nodes and spleen (supplemental Figure 2F). To examine whether our results could also be applied to leukemia, we used a model of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most common leukemia in adults. The Eμ-Tcl-1 mouse model of CLL34-37 develops leukemia at approximately 6 to 9 months of age. The mice exhibit splenomegaly, peripheral blood and BM lymphocytosis, and lymph node infiltration of leukemia cells.34 Thrombocytopenia is evident only at the advanced disease stage.34 We injected IV Eμ-Tcl-1 cells into groups of recipient Mpl−/−, WT, or TpoTg mice and analyzed them 100 days after transplantation (supplemental Figure 2G-J). We found that the burden of leukemia was greater in TpoTg mice than in WT mice based on the increased total lymph node weights (supplemental Figure 2H). Spleen weight and lymphocyte counts tended to increase, albeit variably and did not reach statistical significance in TpoTg mice compared with the WT (supplemental Figure 2G,I). Conversely, Mpl−/− mice showed lower tumor progression than WT mice, reaching significance in lymphocyte counts (supplemental Figure 2G-I). Thus, the results observed in lymphoma may also be relevant to CLL. However, because not all measures of disease were significantly affected in TpoTg or Mpl−/− mice compared with WT mice, future studies are needed to draw definitive conclusions in the CLL model.

Increased lymphoma progression in TpoTg mice. (A) WBC and (B) lymphocyte counts. (C) B-cell numbers in the spleen and (D) spleen weight in WT and Mpl−/− mice 13 days after Eμ-myc 166 IV transplantation (106 P1 cells per mouse). n = 4 to 7 mice per genotype. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Mean ± SEM. Student unpaired t test. (E) WBC and (F) lymphocyte counts, (G) spleen weight, (H) total lymph node (LN) weight, and (I) percentage liver infiltration in WT C57BL/6, Mpl−/−, and TpoTg mice 23 days after Eμ-myc 5903 IV transplantation and 17 days after Eμ-myc 5849 IV transplantation (10 000 P1 cells per mouse). 5903; n = 9 to 10 mice per genotype. 5849; WT (n = 27), Mpl−/− (n = 18), and TpoTg (n = 16) mice. Percentage liver infiltration was assessed in 11 to 12 mice per genotype. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Mean ± SEM. Student unpaired t test, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Increased lymphoma progression in TpoTg mice. (A) WBC and (B) lymphocyte counts. (C) B-cell numbers in the spleen and (D) spleen weight in WT and Mpl−/− mice 13 days after Eμ-myc 166 IV transplantation (106 P1 cells per mouse). n = 4 to 7 mice per genotype. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Mean ± SEM. Student unpaired t test. (E) WBC and (F) lymphocyte counts, (G) spleen weight, (H) total lymph node (LN) weight, and (I) percentage liver infiltration in WT C57BL/6, Mpl−/−, and TpoTg mice 23 days after Eμ-myc 5903 IV transplantation and 17 days after Eμ-myc 5849 IV transplantation (10 000 P1 cells per mouse). 5903; n = 9 to 10 mice per genotype. 5849; WT (n = 27), Mpl−/− (n = 18), and TpoTg (n = 16) mice. Percentage liver infiltration was assessed in 11 to 12 mice per genotype. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Mean ± SEM. Student unpaired t test, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Reduced human NHL lymphoma progression in NSG Mpl−/− mice

Next, we investigated whether TPO-dependent changes in platelet number would influence lymphoma progression in an NSG immunocompromised background (lacking B, T, and natural killer cells) using Eμ-myc 5849 P1 tumor cells or the human B-NHL cell line GRANTA. We used NSG Mpl−/− mice7 with platelet counts ∼5% of the WT NSG levels (70 × 103/μL ± 21 × 103/μL vs 1497 × 103/μL ± 109 ×103/μL, Figure 4A-B). We injected NSG Mpl−/− and control NSG mice with Eμ-myc 5849 P1 tumor cells IV and assessed tumor progression 2 weeks later. GRANTA cells were injected intraperitoneally into NSG Mpl−/− and control NSG mice and tumor progression was assessed 23 days later. We found that NSG Mpl−/− mice had reduced disease progression in both lymphoma models compared with control NSG mice, as shown by reduced numbers of total peripheral WBCs and lymphocytes, whereas the spleen size was unaffected (Figure 4B-H). Hence, reduced platelet numbers in NSG Mpl−/− mice were associated with slowed lymphoma progression also in the absence of a functional immune system. Importantly, the reduction in lymphoma burden observed in NSG Mpl−/− mice using the GRANTA cell model confirmed that murine Eμ-myc results are relevant to human lymphoma cells.

Reduced disease progression in NSG Mpl−/− mice. Eμ-myc 5849 (104 P1) tumor cells were injected IV into NSG and NSG Mpl−/− mice 14 days before analysis. (A) Platelet count, (C) WBC count, (E) lymphocyte count, and (G) spleen weight. Mean ± SEM. n = 3 to 5 mice per genotype (Eμ-myc transplant). n = 10 to 14 mice per genotype (without transplantation). Spleen (n = 3-6 mice without transplantation per genotype). Human GRANTA (2 × 106) tumor cells were injected intraperitoneally into NSG and NSG Mpl−/− mice 23 days before analysis. (B) Platelet count, (D) WBC count, (F) lymphocyte count, and (H) spleen weight. Mean ± SEM. n = 8 to 11 mice per genotype (GRANTA transplant). n = 3 to 6 mice per genotype (without transplantation). Male and female mice. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. One-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test were performed on data that passed the Shapiro-Wilks normality test, panels A, C, D, F, and G. Student unpaired t test with Mann Whitney U test were performed for data that did not pass the normality test, panels B, E, and H. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Reduced disease progression in NSG Mpl−/− mice. Eμ-myc 5849 (104 P1) tumor cells were injected IV into NSG and NSG Mpl−/− mice 14 days before analysis. (A) Platelet count, (C) WBC count, (E) lymphocyte count, and (G) spleen weight. Mean ± SEM. n = 3 to 5 mice per genotype (Eμ-myc transplant). n = 10 to 14 mice per genotype (without transplantation). Spleen (n = 3-6 mice without transplantation per genotype). Human GRANTA (2 × 106) tumor cells were injected intraperitoneally into NSG and NSG Mpl−/− mice 23 days before analysis. (B) Platelet count, (D) WBC count, (F) lymphocyte count, and (H) spleen weight. Mean ± SEM. n = 8 to 11 mice per genotype (GRANTA transplant). n = 3 to 6 mice per genotype (without transplantation). Male and female mice. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. One-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test were performed on data that passed the Shapiro-Wilks normality test, panels A, C, D, F, and G. Student unpaired t test with Mann Whitney U test were performed for data that did not pass the normality test, panels B, E, and H. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Pharmacological inhibition of platelet function or anticoagulation did not improve disease outcome

Next, we considered the role of platelet activation by inhibition using the common antiplatelet agents aspirin38 (a cyclooxygenase inhibitor) and clopidogrel39 (a platelet P2Y12 adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibitor) as single agents. Aspirin was administered orally at 25 mg/kg in drinking water to mice pretreated 1 week before Eμ-myc 5849 tumor injection. However, no significant difference in disease outcome was detected between aspirin-treated mice and the vehicle control group (supplemental Figure 3A). When WT mice were administered either clopidogrel (50 mg/kg) or vehicle by oral gavage daily starting 1 day before Eμ-myc 5849 transplantation, we noted increased WBC counts in the treated group compared with the vehicle control group (supplemental Figure 3B). Finally, we treated mice with the anticoagulant low molecular weight heparin enoxaparin sodium40 at 5 and 10 mg/kg with mice being pretreated for 1 day before Eμ-myc 5849 tumor cell injection. Again, we observed no change between the treated mice and the vehicle control group (supplemental Figure 3C). Taken together, the pharmacological inhibition of platelet activation or anticoagulation did not improve disease outcomes at the concentrations and schedules used.

Transient or sustained platelet depletion did not positively affect disease outcome

We next examined whether transient platelet depletion would influence Eμ-myc lymphoma progression by IV injection of antiplatelet serum (APS), leading to dramatically reduced platelet counts within 24 hours followed by a recovery phase.41 Platelets were depleted on day 0, 1 day before Eμ-myc 5849 tumor injection, a method previously shown to lower tumor burden in a mouse model of lung adenocarcinoma.7 However, we did not observe significant differences in lymphoma progression when comparing APS-treated and control mice (Figure 5A-C). We also depleted platelets on days 0, 3, and 6 to maintain low platelet counts for ∼8 days, with tumor cells being injected on day 1. Nevertheless, the disease outcome was also unaffected by this strategy (Figure 5A-C). Although transient thrombocytopenia at the time of tumor administration and in the early phase did not affect disease outcomes, sustained thrombocytopenia might influence tumor progression differently, as observed in thrombocytopenic Mpl−/− and NSG Mpl−/− mice. We used an alternative model of thrombocytopenia, the Bcl-xPlt20/Plt20 mouse, with platelet counts ∼25% of the WT caused by reduced platelet life span.27 However, no marked differences were observed between WT and Bcl-xPlt20/Plt20 mice in the Eμ-myc 5849 tumor load at 20 days after transplant (Figure 5D-G). One important difference between the 2 thrombocytopenic models is that although megakaryocyte numbers are markedly reduced in Mpl−/− mice, they are slightly elevated in Bcl-xPlt20/Plt20 mice.42 These data suggest that the differences in lymphoma burden observed in TpoTg and Mpl−/− mice may not be directly related to platelet number, although a role for megakaryocytes cannot be excluded.

Transient or sustained platelet reduction did not affect disease outcome. Eμ-myc 5849 immortalized tumor cells (2 × 104) were transplanted IV on day 1, and acute thrombocytopenia was induced by APS IV injection on days 0, 3, and 6 in male WT C57BL/6 mice. Mice were analyzed on day 16. (A) WBC count, (B) lymphocyte count, and (C) spleen weight. Mean ± SEM. n = 4 to 8 mice per group. The data passed the Shapiro-Wilks normality test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test. WT and thrombocytopenic Bcl-xPlt20/Plt20 male mice were transplanted IV with Eμ-myc 5849 tumor cells (2 × 104), and mice were analyzed on day 20. (D) WBC count, (E) lymphocyte count, (F) spleen weight, and (G) platelet count. Mean ± SEM. n = 4 to 8 mice per group. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Student unpaired t test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .0052, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Transient or sustained platelet reduction did not affect disease outcome. Eμ-myc 5849 immortalized tumor cells (2 × 104) were transplanted IV on day 1, and acute thrombocytopenia was induced by APS IV injection on days 0, 3, and 6 in male WT C57BL/6 mice. Mice were analyzed on day 16. (A) WBC count, (B) lymphocyte count, and (C) spleen weight. Mean ± SEM. n = 4 to 8 mice per group. The data passed the Shapiro-Wilks normality test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test. WT and thrombocytopenic Bcl-xPlt20/Plt20 male mice were transplanted IV with Eμ-myc 5849 tumor cells (2 × 104), and mice were analyzed on day 20. (D) WBC count, (E) lymphocyte count, (F) spleen weight, and (G) platelet count. Mean ± SEM. n = 4 to 8 mice per group. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Student unpaired t test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .0052, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

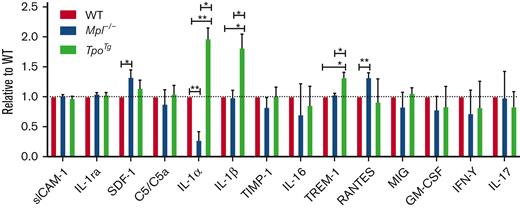

Proinflammatory BM microenvironment in TpoTg mice

To explore the potential role of the tumor microenvironment, we performed cytokine analysis of the BM fluid of Mpl−/−, WT, and TpoTg mice. Our results showed increased protein levels of the proinflammatory molecules IL-1α and IL-1β in TpoTg BM fluid when compared with the WT (Figure 6). By contrast, the Mpl−/− BM fluid had reduced levels of IL-1α compared with the WT (Figure 6). Modest increases were also noted in the levels of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cell 1 protein in TpoTg BM fluid and of regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted and stromal cell–derived factor 1 in Mpl−/− BM fluid compared with those in the WT (Figure 6). Megakaryocytes have been shown to contain IL-143-48 and were capable of producing IL-1 both directly and by IL-1 containing microvesicles.44 Furthermore, megakaryocytes can promote systemic inflammation through microvesicles rich in IL-1,44,49 raising the possibility that megakaryocytes could also contribute to inflammation in lymphoma. Our results suggest that the BM microenvironment may be proinflammatory in TpoTg mice compared with that in WT mice, a situation reversed in Mpl−/− mice, and that megakaryocytes present in increased numbers in TpoTg BM could be a potential source of proinflammatory IL-1.

Proinflammatory BM microenvironment in TpoTg mice. Cytokine and chemokine analysis of BM fluid from WT, Mpl−/−, and TpoTg mice with Proteome profiler array (mouse cytokine array panel A). The figure includes cytokine and chemokines that were detected in BM fluid and excludes proteins that were below detection level. n = 4 samples per genotype. Each sample was combined from 2 mice of the same genotype (a total of 8 mice were included per genotype). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Only significantly different changes are indicated. 3 independent experiments. Student unpaired t test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005.

Proinflammatory BM microenvironment in TpoTg mice. Cytokine and chemokine analysis of BM fluid from WT, Mpl−/−, and TpoTg mice with Proteome profiler array (mouse cytokine array panel A). The figure includes cytokine and chemokines that were detected in BM fluid and excludes proteins that were below detection level. n = 4 samples per genotype. Each sample was combined from 2 mice of the same genotype (a total of 8 mice were included per genotype). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Only significantly different changes are indicated. 3 independent experiments. Student unpaired t test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005.

Enhanced proinflammatory Eμ-myc gene expression in TpoTg mice

Next, we performed RNA sequencing of flow cytometry sorted mCherry positive Eμ-myc tumor cells residing in blood from lymphoma-bearing WT and TpoTg mice after Eμ-myc 5849 tumor transplantation to look at differences in gene expression. As expected, Eμ-myc tumor-bearing TpoTg mice had increased WBC and lymphocyte counts compared with WT mice that underwent transplantation (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Considering the hallmark gene sets, we focused on pathways associated with inflammation. In blood-residing Eμ-myc cells in TpoTg mice, hallmark gene sets associated with inflammatory response, IL-2 Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5 (STAT 5) signaling, and TNF-α signaling via Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) were significantly upregulated compared with the WT (Figure 7A). Specific genes upregulated in these proinflammatory pathways are highlighted in a mean difference plot (Figure 7B) and specified in supplemental Table 1. Furthermore, in support of a procoagulant state, we noted upregulated hallmark gene sets associated with coagulation close to significance in blood-residing Eμ-myc cells in TpoTg mice (Figure 7A). In summary, it appears that the tumor microenvironment in TpoTg mice provided a proinflammatory stimulus potentially through IL-1 in Eμ-myc tumor cells.

Inflammatory response in Eμ-myc lymphoma cells residing in TpoTg mice. (A) Pathway analysis of hallmark gene sets in blood-residing Eμ-myc lymphoma cells of TpoTg mice was compared with WT mice. Significantly upregulated pathways associated with inflammation are indicated with asterisks. (B) Differentially expressed genes are presented in a mean difference plot when comparing blood-residing Eμ-myc cells of TpoTg mice with WT mice. Significantly upregulated genes are indicated in red and downregulated genes in blue. Significantly upregulated genes associated with an inflammatory response are circled in green. They include hallmark gene sets: inflammatory response, IL-2 STAT 5 signaling, and TNF-α signaling via NF-κB. FDR, false discovery rate.

Inflammatory response in Eμ-myc lymphoma cells residing in TpoTg mice. (A) Pathway analysis of hallmark gene sets in blood-residing Eμ-myc lymphoma cells of TpoTg mice was compared with WT mice. Significantly upregulated pathways associated with inflammation are indicated with asterisks. (B) Differentially expressed genes are presented in a mean difference plot when comparing blood-residing Eμ-myc cells of TpoTg mice with WT mice. Significantly upregulated genes are indicated in red and downregulated genes in blue. Significantly upregulated genes associated with an inflammatory response are circled in green. They include hallmark gene sets: inflammatory response, IL-2 STAT 5 signaling, and TNF-α signaling via NF-κB. FDR, false discovery rate.

Discussion

Our study identified that Eμ-myc lymphoma cells, when transplanted into TpoTg mice with a baseline of high megakaryocyte and platelet numbers, exhibited enhanced lymphoma progression, with increased WBC counts, spleen and lymph node weights, and liver infiltration compared with WT mice that underwent transplantation. Conversely, the tumor burden was modestly reduced in Mpl−/− mice, with a baseline phenotype of low megakaryocyte and platelet numbers. Similar results were observed upon transplantation of the human NHL GRANTA cell line or Eμ-myc cells into an Mpl-deficient thrombocytopenic and immunocompromised mouse model. Moreover, the results were shown to be potentially applicable to CLL when using the Eμ-Tcl-1 model; however, further research is needed to draw definitive conclusions regarding CLL.

In our murine Eμ-myc NHL-model, we found evidence of increased platelet activation with subsequent degranulation, based on increased serum levels of soluble P-selectin. The majority of soluble P-selectin is thought to be derived from platelets,30 although we acknowledge that endothelial cells may also have contributed. NHL is listed among the neoplasias with a high risk of venous thromboembolism18 and in support of this, our results indicate that platelets degranulate in mice with increasing Eμ-myc lymphoma load. Moreover, RNA sequencing of Eμ-myc lymphoma cells from the blood of WT and TpoTg mice that underwent transplantation identified upregulated hallmark gene sets of coagulation close to significance in TpoTg mice, which exhibit a greater tumor burden than WT mice.

Platelets are known to release a range of growth factors when activated50 that can contribute to the enhanced survival of tumor cells in coculture assays in vitro, as previously reported.21,22 In our study, platelets or PRMs also enhanced the survival of Eμ-myc cell lines in a setting when the lymphoma cells were stressed by serum starvation. However, using pharmacological inhibition of platelet function, anticoagulation, acute thrombocytopenia, or chronic Bcl-xL–dependent thrombocytopenia, we could not find support in vivo for platelets significantly contributing to advancing lymphoma in the Eμ-myc transplant model of NHL.

In a previous study, we examined lymphomagenesis and the preneoplastic phase in Eμ-myc mice, where Mpl−/− Eμ-myc mice exhibited an enhanced preneoplastic phase with increased numbers of PreB2 and immature B cells and augmented blood lymphocyte counts.33 In this study, however, we scrutinized the effect of Eμ-myc lymphoma progression after transplantation of established tumor cells into mice with modulated megakaryocyte and platelet numbers. In this study, a direct effect of TPO on Eμ-myc lymphoma cells was unlikely, as elevated TPO levels were present in both the TpoTg mice42 and Mpl−/− mice compared with WT animals.42,51

Lymphoma cells require growth factors and cytokines derived from the microenvironment for their nourishment and growth,52 and inflammatory status provoked by the tumor microenvironment plays an important role in the disease progression of NHLs.53 We identified the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α and IL-1β to be elevated in the BM microenvironment of the TpoTg mouse compared with WT mice, whereas IL-1α levels were reduced in Mpl−/− mice. Megakaryocytes were present at 3-fold increased numbers in TpoTg BM, compared with WT, but are reduced in Mpl−/− mice5,25,42 and could be a potential source of IL-1. A recent report demonstrated that lung megakaryocytes are immune modulatory cells and that this can also be the case for BM-residing megakaryocytes dependent on stimulus.54 Moreover, megakaryocytes have been shown to promote systemic inflammation through microvesicles rich in IL-1,44,49 raising the possibility that megakaryocytes could contribute to systemic inflammation in lymphoma. The involvement of other BM cells known to produce IL-1, such as fibroblasts, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells55 was not assessed.

IL-1β has a protumorigenic role across all cancer types56 and is viewed as an attractive target for pharmacological intervention. Importantly, increased IL-1β in serum is a marker associated with poor prognosis in lymphoma, correlating with increased relapse rates in patients with HL.57 IL-1β has also been shown to drive the expression and production of other downstream protumorigenic cytokines and growth factors, including IL-6, transforming growth factor-beta, TNF-α, and epidermal growth factor in other cancers.56 Tumor-promoting effects of IL-1α have been reported, with high levels correlating with metastatic disease, tumor dedifferentiation, and lymph angiogenesis.56 Supporting this finding, we observed enhanced liver dissemination of lymphoid tumor cells in TpoTg mice.

We found evidence of a response to a proinflammatory microenvironment reflected in Eμ-myc tumor cells. In blood-residing Eμ-myc cells from TpoTg mice, hallmark gene sets associated with inflammatory response, IL-2 STAT 5 signaling, and TNF-α signaling via NF-κB were upregulated. Notably, increased serum levels of TNF-α and IL-2 are both markers associated with poor prognosis in patients with NHL.53,57

The Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study provided proof of the potential of IL-1 neutralization in cancer. Patients with stable coronary artery disease, without a diagnosis of cancer at the time of enrollment, were treated with the anti–IL-1β antibody canakinumab. The antibody significantly lowered overall cancer mortality, particularly in lung cancer.58 These findings simulated several clinical trials that studied blocking of IL-1β and other inflammatory interleukins in cancer. Of interest for hematologic malignancy, a phase 2 trial studying canakinumab monotherapy in myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelogenous leukemia was initiated in 2020 (#NCT04239157). Moreover, Anakinra is an IL-1R antagonist in clinical trials for cancer therapy as monotherapy in B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia, B-cell lymphoma, B-cell NHL initiated 2019 (#NCT04148430), and multiple myeloma initiated 2017 and 2019 and in combination therapy in other cancers.55

A recent study demonstrated that platelets enhanced multiple myeloma progression via IL-1β upregulation.24 In this study we discovered that a proinflammatory microenvironment with elevated BM IL-1 levels promoted Eμ-myc lymphoma progression in transgenic mice with elevated TPO levels and megakaryocyte numbers. Conversely, lymphoma progression was suppressed in Mpl−/− mice, with reduced megakaryocyte and IL-1 levels. It is tempting to speculate that megakaryocytes or megakaryocytic microvesicles may be a potential source of IL-1. The outcome of clinical trials blocking IL-1β or IL1-R in patients with lymphoma will reveal the clinical significance of our findings in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stefan Glaser for providing the pMSCV-Luc2-IRES-mCherry retroviral vector; Stanley Lee for providing Eμ-myc cell lines; Benjamin Kile for providing Bcl-xPlt20/Plt20 mice; David Huang for providing Eμ-Tcl-1 mice; Keti Stoev, Nicole Lynch, Stephanie Bound, Jasmine McManus, Janelle Lochland, and Lachlan Whitehead for outstanding technical assistance; and Anastasia Tikhonova for methodological advice on cytokine analysis of BM fluid. The visual abstract was created using BioRender.com.

This work was generously supported by grant funds received from the following sources: Leukaemia Foundation Australia Grant-in-Aid (E.C.J. and K.D.M.), Sir Edward Dunlop Medical Research Foundation (E.C.J.), a project grant from the CASS Foundation (A.E.A.), the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Project (1079250) (E.C.J.) and Program (1113577) Grants and Fellowship (1058344) (W.S.A.), an Independent Research Institutes Infrastructure Support Scheme Grant (9000587), and a Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support Grant. E.C.J. is the recipient of a fellowship from the Lorenzo and Pamela Galli Charitable Trust. S.R.H. is the recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Award from the University of Melbourne.

Authorship

Contribution: A.E.A., J.C., M.L., P.G., F.Y., S.R.H., and P.C. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data; A.L.G. and C.S.N.L.-W.-S. performed the bioinformatics analysis; E.C.J., W.S.A., K.D.M., L.C., D.M., A.L.G., C.S.N.L.-W.-S., A.E.A., J.C., M.L., P.G., and S.R.H. contributed to intellectual discussions of the data; W.S.A. provided Mpl−/− and TpoTg mice; E.C.J. designed the project, prepared figures, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Emma C. Josefsson, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1G Royal Parade, Parkville, VIC 3052, Australia; e-mail: josefsson@wehi.edu.au.

References

Author notes

∗A.E.A. and J.C. contributed equally to this study.

Gene expression data are available at Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE199782 and access code sroveoyyxdohnab.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Emma C. Josefsson (josefsson@wehi.edu.au).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.