Key Points

Symptoms often considered related to oral iron supplementation are commonly seen in pregnancy and may improve as pregnancy progresses.

A daily oral iron dosing schedule might deliver an adequate iron load to cope with the increased iron demands in pregnant women without anemia.

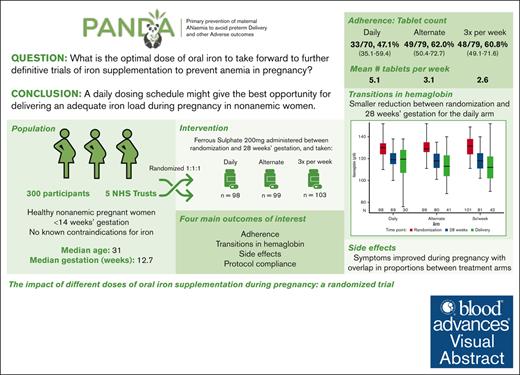

Visual Abstract

Oral iron is first-line medication for iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy. We conducted a pilot randomized trial to investigate the impact of different doses of oral iron supplementation started early in pregnancy on women without anemia for 4 main outcomes: recruitment and protocol compliance, adherence, maintenance of maternal hemoglobin, and side effects. At antenatal clinic visits, participants were allocated to 1 of 3 trial arms in a 1:1:1 ratio: 200 mg ferrous sulfate daily, alternate days, or 3 times per week. The participants were followed to delivery. Baseline characteristics of 300 recruited participants were well matched between trial arms. The mean proportion of tablets taken as expected per participant was 82.5% overall (72.3%, 89.6%, and 84.5% for the daily, alternate days, and 3 times a week arm, respectively). There was a lower overall adherence rate in the daily arm (47%) than in the alternate days (62%) and the 3 times per week (61%) arms. A reduction in hemoglobin between randomization and 28 weeks’ gestation seemed smaller for the daily arm. A range of side effects were commonly reported at baseline before starting interventions and at later antenatal visits. Many side effects of iron overlapped with normal pregnancy symptoms. A daily iron dosing schedule might give the best opportunity for delivering an adequate iron load during pregnancy in women without anemia. Further randomized trials powered on clinical outcomes are needed to establish the clinical effectiveness of oral iron supplementation to prevent iron deficiency anemia. This study was registered (#ISRCTN12911644).

Introduction

Anemia develops in around a third of women during pregnancy in all countries and is primarily caused by iron deficiency.1-4 The consequences of anemia and low iron are broad and may include maternal mortality and maternal symptoms such as fatigue and mood disturbances and impacts on preterm birth and stillbirth, and iron deficiency may also have long-term effects on fetal and infant brain development.5-16

Oral iron supplementation remains the standard therapy for iron deficiency.17,18 However, the optimal dose or schedule for oral iron administration in pregnancy has not been established. There is a balance between the use of higher doses of iron to provide more daily iron to increase hemoglobin (Hb) more rapidly and the higher rates of side effects, which can lead to discontinuation of therapy and reduced overall total dose taken.19 Ingestion of even single doses of oral iron leads to a rapid rise in serum hepcidin, a key regulator of iron.20,21 Hepcidin blocks absorption of subsequent doses of iron if taken before hepcidin levels fall back to baseline. Therefore, doses taken on less frequent schedules have been reported to increase the proportion of iron absorbed per dose and fewer side effects.22,23 Although studies of iron fractional absorption have been described in nonpregnant, healthy volunteers, data are limited in pregnancy during which hepcidin is physiologically markedly more suppressed.24

Oral iron supplementation may have a preventive role and may reduce the burden of anemia and its associated complications. Anemia is more commonly diagnosed in the third trimester because of the increased demands of iron for the growing fetus, the placenta, and the mother. Therefore, administration of iron in early pregnancy may reduce the rates of maternal anemia and the associated complications of iron depletion in both the mother and infant later in pregnancy.

This pilot trial was conducted to investigate the impact of different dosing schedules of oral iron supplementation started early in pregnancy in women without anemia. The overarching aim was to inform the optimal dosing regimen to take forward into further definitive trials of iron supplementation focused on preventing anemia that commonly develops later in pregnancy. We measured outcomes to evaluate whether any dose schedule selected for a large prevention trial would be jeopardized by significant nonadherence during pregnancy. We also recognized that the side effects of iron use would likely overlap with normal pregnancy symptoms; therefore, we wished to monitor the potential side effect profile longitudinally.

Methods

This was a registered, pilot, phase 3, multicenter, 3-arm, open-label, randomized trial that was conducted as part of the PANDA research programme.25 Participants were allocated to 200 mg ferrous sulfate daily or on alternate days or 3 times per week. Public involvement was provided through an established group, the Nottingham Maternity Research Network, that has informed the research since preapplication. Details of service user engagement for patient public involvement (PPI) are summarized in Table 1.

Service user/PPI contributions and their impacts

| Who was involved and how . | Stage and contribution . | Impact . |

|---|---|---|

| Application development | ||

| Nottingham Maternity Research Network (NMRN) members. Three in-person meetings, chief investigator, patient and public involvement (PPI) Lead | Discussion of:

| Study supported: NMRN to provide ongoing advice Two NMRN members joined the research team and were named Service User Coinvestigators (SUCoIs). Informed:

|

| Planning, interpretation, and reporting of dose-finding study | ||

| NMRN meetings, chief investigator, PPI Lead SUCoIs Project management group (PMG) Written feedback | Collection of self-reported data Discussion of:

|

|

| SUCoIs, PPI Lead Written feedback PMG | Feedback on participant-facing materials and protocol:

|

|

| SUCoIs Feedback on analytical report PMG Written feedback on draft | Interpretation of findings and relative emphasis of impacts on clinical measurements vs side effects Output Minutes | Incorporated |

| Trial Steering Committee (TSC) | Trial oversight |

|

| Who was involved and how . | Stage and contribution . | Impact . |

|---|---|---|

| Application development | ||

| Nottingham Maternity Research Network (NMRN) members. Three in-person meetings, chief investigator, patient and public involvement (PPI) Lead | Discussion of:

| Study supported: NMRN to provide ongoing advice Two NMRN members joined the research team and were named Service User Coinvestigators (SUCoIs). Informed:

|

| Planning, interpretation, and reporting of dose-finding study | ||

| NMRN meetings, chief investigator, PPI Lead SUCoIs Project management group (PMG) Written feedback | Collection of self-reported data Discussion of:

|

|

| SUCoIs, PPI Lead Written feedback PMG | Feedback on participant-facing materials and protocol:

|

|

| SUCoIs Feedback on analytical report PMG Written feedback on draft | Interpretation of findings and relative emphasis of impacts on clinical measurements vs side effects Output Minutes | Incorporated |

| Trial Steering Committee (TSC) | Trial oversight |

|

Center and participant recruitment

Participating sites were purposefully selected to include those with diverse racial and ethnic composition. Pregnant women were assessed for suitability to be approached to consider participation using reference to the eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria were (1) healthy pregnant women without anemia (Hb concentration ≥110 g/L) who were aged ≥18 years and (2) a gestational age of 13 weeks + 6 days or less. Exclusions included known hemoglobinopathies (women with hemoglobinopathy trait were eligible) or hemochromatosis, a preexisting known diagnosis of anemia, severe gastrointestinal disease (affecting tolerability of oral iron), allergies to iron, multiple pregnancies (given the higher iron demands), and recent red cell transfusion within 1 month. We did not exclude women who elected to take iron-containing (over-the-counter) supplements after input from our PPI group with a desire to keep the study pragmatic; this information was recorded and a sensitivity analysis was planned.

Screening and informed consent

Women were provided with information at the first-trimester clinic booking, at the dating ultrasound scan appointment, or during a routine antenatal clinic visit at 13 weeks + 6 days gestation or earlier. Routine antenatal blood results were used for screening by the research team against the eligibility criteria. Informed consent to enter the trial was collected by delegated research staff.

Allocation

Participants were randomized to 1 of the 3 trial arms in a 1:1:1 ratio. Randomization was performed using an online web response randomization service (Sealed Envelope) with stratification by center and was conducted using randomly permuted blocks of undisclosed size. Participants were also independently allocated in a 1:1 ratio to receive a Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) bottle cap (with sensors that record each time the bottle is opened) to provide additional data about patterns of adherence in a sample of participants.

Interventions

Oral iron supplements

Oral iron supplements were prescribed as per the allocated arm (200 mg ferrous sulfate daily vs 200 mg ferrous sulfate on alternate days vs 200 mg ferrous sulfate 3 times per week [eg, Monday, Wednesday, and Friday]) and dispensed through the local hospital pharmacy. The protocol allowed for dose modifications if the prescribed iron dose was not tolerable, for example from daily to alternate daily. Details of all dose adjustments were recorded.

Intervention to support medication adherence

Based on the knowledge of barriers to and enablers of medication adherence during pregnancy, we developed an intervention to support adherence to oral iron supplements in the context of prevention of anemia in pregnancy.26-30 In brief, formative qualitative interviews with pregnant women and health care professionals identified key barriers, including forgetting, concerns about safety, perceived necessity, and competing health priorities, and a range of potential enablers (building routines, prompts, and perceived benefits). We developed a multicomponent intervention (composed of structured education around anemia and iron supplementation in pregnancy, goal setting, action planning, problem solving, and text message reminders) to support adherence, which was piloted and delivered to a subgroup of 60 trial participants. Full details of these methods and results will be provided in a separate adherence publication. The subgroup of participants who received the adherence intervention was spread equally across the 3 trial arms. A sensitivity analysis examined tablet count adherence in participants who did not receive the medication adherence intervention.

Outcomes

There were 4 main (coprimary) outcomes of interest, namely recruitment and protocol compliance, adherence, maintenance of maternal Hb, and side effects. Tablet count data were prespecified as the main measure of adherence.

Trial assessments

Baseline information (including weight and height, previous pregnancies, previous anemia, ethnicity) was collected at randomization. A clinical decision guide (see “Appendix”) was completed at baseline and at follow-up to record a range of symptoms relevant to anemia and the use of oral iron. At 16 weeks’ gestation (±2 weeks) and 24 weeks’ gestation (±2 weeks), the research team contacted participants telephonically, through email, or in face-to-face consultation to inquire about side effects. At 28 weeks’ gestation (±2 weeks), a count of tablets in the returned oral iron supplement bottles was performed and MEMS data were downloaded (if applicable). In addition, any changes to concomitant medications were recorded, and the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-5) (reference) participant questionnaire was completed.31 At childbirth, information on selected infant outcomes and maternal data were collected by the research teams. All serious adverse events that occurred between consent and the 28-week gestation follow-up were submitted for review within 24 hours of observing or learning of the event.

In addition, the progression criteria for proceeding from a pilot trial to a main definitive trial were predefined and agreed upon (supplemental Figure 10). A traffic light system (red, do not proceed; amber, consider protocol adjustments; green, proceed) was applied to these criteria to assess recruitment, adherence, and fidelity.

Sample size

For this pilot trial, no formal sample size calculation was required. Instead, the sample size was based on an acceptable level of precision for the estimated adherence rates (for a point estimate of 85% adherence, a sample size of 80 participants in each of 3 arms gave a 95% confidence interval [CI] from 77%-93%).

Statistical considerations

A statistical analysis plan was finalized before completion of study recruitment (supplement). An intention-to-treat approach was used. Adherence to oral iron was primarily assessed using the count of returned tablets at the 28-week visit. A participant was considered to be adherent if the number of tablets returned was ±15% of the number expected. The overall adherence rates were calculated for each arm of the trial and as the mean proportion of doses taken per participant by arm. The median MARS-5 medication adherence questionnaire scores from the 28-week visit were compared among the treatment arms. The MEMS cap recorded every occasion the bottle was opened from treatment initiation until the 28-week visit. The proportion of doses taken as planned according to the MEMS data was calculated. If the cap indicated that the bottle was opened as expected for at least 85% of expected doses, then the participant was considered to be adherent. The overall MEMS adherence rate was calculated and the mean proportion of doses taken as expected per participant by arm was also calculated.

The maintenance of Hb was assessed by calculating the change in concentration between randomization and 28 weeks’ gestation. A linear regression was used to calculate the mean differences with adjustment for Hb at randomization. The proportion of participants who maintained their Hb above the diagnostic thresholds for anemia in pregnancy, by trimester, was also calculated using recommendations in national guidelines.17 Descriptive statistics were used to present findings on the type, frequency, and severity of recorded symptoms at baseline and follow-up. Sankey diagrams were used to visualize the data. The proportion of eligible participants who enrolled and completed the trial visits and the data collection was calculated for each arm. The proportion of eligible women who provided consent during recruitment, the attrition rates, and data completeness rates were also calculated.

Governance and trial oversight

Trial procedures were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (2013). The overall trial sponsor was the National Health Service (NHS) Blood and Transplant. The trial was approved by the relevant ethics committee (Wales Research Ethics Committee 5; 21/WA/0247). A Trial Steering Committee provided overall trial supervision. A core Data Monitoring Committee provided advice to the Trial Steering Committee chair regarding the ongoing trial conduct and safety of patients.

Results

Recruitment and protocol compliance

Recruitment commenced in January 2022. Across 5 NHS Trusts, an initial recruitment target of 240 participants was achieved in June 2022. Recruitment was extended to 300 participants to gather additional data and to further pilot the intervention aimed at improving medication adherence.

Overall, the consent rate for the trial was 42.3% (95% CI, 38.6-46.0). There were no participants randomized in error. Of the 300 participants, 98 were randomized to the daily arm, 99 to the alternate arm, and 103 to the 3 times a week arm. Visit completeness varied; 80.3% completed 28 weeks and 83.7% completed follow-up to childbirth (Figure 1). The overall completeness rate was 62% (95% CI, 56.2-67.5). This reflected participants who were enrolled, completed the trial visits, completed some side effect reporting, for whom adherence data were completed and Hb levels were reported at baseline and at 28 weeks, and who completed the MARS-5 questionnaire.

Withdrawals and data completion

There were 41 participants who withdrew from treatment only (ie, continued with the trial visits and assessments; 11 from the daily arm, 14 from the alternate arm, and 16 from the 3 times a week arm). A total of 23 participants withdrew fully from the trial (10 from the daily arm, 3 from the alternate arm, and 10 from the 3 times a week arm). The most common reason for withdrawal was side effects. A further 5 participants were withdrawn because of early pregnancy loss. No participants withdrew consent for their data to be used in the trial.

There were 20 participants (6.7%) who were reported as lost to follow-up at some point in the trial; however, birth data were obtained for 16 of these 20 participants using patient health records. In total, there were 16 participants with a protocol deviation (5.3%), including visits not completed in the time window, questionnaires not completed, MEMS cap data not being available, and participants not returning their tablet bottle at 28 weeks’ gestation.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of recruited participants were well matched between trial arms (Table 2; supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

Baseline characteristics

| . | Daily (n = 98) . | Alternate (n = 99) . | Three times a week (n = 103) . | Total (N = 300) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 31 (27-35) | 31 (27-35) | 30 (27-34) | 30.5 (27-34) |

| Socioeconomic status∗ (quintile) | ||||

| 1 (most deprived) | 20 (34.5) | 18 (28.1) | 16 (22.9) | 54 (28.1) |

| 2 | 11 (19.0) | 17 (26.6) | 29 (41.4) | 57 (29.7) |

| 3 | 8 (13.8) | 9 (14.1) | 8 (11.4) | 25 (13.0) |

| 4 | 11 (19.0) | 11 (17.2) | 9 (12.9) | 31 (16.1) |

| 5 (least deprived) | 8 (13.8) | 9 (14.1) | 8 (11.4) | 25 (13.0) |

| Gestation (wk) | 12.7 (12.1-13.1) | 12.7 (12.3-13.1) | 12.7 (12.3-13.1) | 12.7 (12.3-13.1) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 85 (86.7) | 83 (83.8) | 91 (88.3) | 259 (86.3) |

| Mixed | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.9) | 4 (1.3) |

| Asian or Asian British | 9 (9.2) | 13 (13.1) | 5 (4.9) | 27 (9.0) |

| Black, African, Caribbean, Black British | 2 (2.0) | 3 (3.0) | 3 (2.9) | 8 (2.7) |

| Other | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Smoker | 13 (13.3) | 5 (5.1) | 6 (5.8) | 24 (8.0) |

| Height (cm) | 164 (160-168) | 165 (159-169) | 163 (160-170) | 164 (160-169) |

| Weight (kg) | 70 (61-83) | 70 (62-85) | 74.4 (62.7-84.7) | 70.5 (62-84) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 (22.9-31.2) | 26.5 (23-31.6) | 27.3 (23.5-31.2) | 26.5 (23.1-31.2) |

| Parity | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) |

| Hb (g/L) | 130 (124-135) | 129 (126-135) | 132 (124-138) | 130 (125-136) |

| Iron-containing supplements being taken at baseline† | 22 (22.9) | 24 (26.7) | 17 (17.7) | 63 (22.3) |

| Known hemoglobinopathy trait | 3 (3.1) | 4 (4.0) | 4 (3.9) | 11 (3.7) |

| Previous anemia | ||||

| Outside of pregnancy | 12 (12.2) | 6 (6.1) | 12 (11.7) | 30 (10.0) |

| During pregnancy | 5 (5.1) | 7 (7.1) | 10 (9.7) | 22 (7.3) |

| Both | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Comorbidity‡ | 9 (9.2) | 11 (11.1) | 18 (17.5) | 38 (12.7) |

| At least 1 previous termination | 12 (12.2) | 13 (13.1) | 14 (13.6) | 39 (13.0) |

| At least 1 previous miscarriage or still birth | 30 (30.6) | 27 (27.3) | 32 (31.1) | 89 (29.7) |

| At least 1 previous postpartum hemorrhage (>1/L) | 3 (3.1) | 7 (7.1) | 11 (10.7) | 21 (7.0) |

| . | Daily (n = 98) . | Alternate (n = 99) . | Three times a week (n = 103) . | Total (N = 300) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 31 (27-35) | 31 (27-35) | 30 (27-34) | 30.5 (27-34) |

| Socioeconomic status∗ (quintile) | ||||

| 1 (most deprived) | 20 (34.5) | 18 (28.1) | 16 (22.9) | 54 (28.1) |

| 2 | 11 (19.0) | 17 (26.6) | 29 (41.4) | 57 (29.7) |

| 3 | 8 (13.8) | 9 (14.1) | 8 (11.4) | 25 (13.0) |

| 4 | 11 (19.0) | 11 (17.2) | 9 (12.9) | 31 (16.1) |

| 5 (least deprived) | 8 (13.8) | 9 (14.1) | 8 (11.4) | 25 (13.0) |

| Gestation (wk) | 12.7 (12.1-13.1) | 12.7 (12.3-13.1) | 12.7 (12.3-13.1) | 12.7 (12.3-13.1) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 85 (86.7) | 83 (83.8) | 91 (88.3) | 259 (86.3) |

| Mixed | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.9) | 4 (1.3) |

| Asian or Asian British | 9 (9.2) | 13 (13.1) | 5 (4.9) | 27 (9.0) |

| Black, African, Caribbean, Black British | 2 (2.0) | 3 (3.0) | 3 (2.9) | 8 (2.7) |

| Other | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Smoker | 13 (13.3) | 5 (5.1) | 6 (5.8) | 24 (8.0) |

| Height (cm) | 164 (160-168) | 165 (159-169) | 163 (160-170) | 164 (160-169) |

| Weight (kg) | 70 (61-83) | 70 (62-85) | 74.4 (62.7-84.7) | 70.5 (62-84) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 (22.9-31.2) | 26.5 (23-31.6) | 27.3 (23.5-31.2) | 26.5 (23.1-31.2) |

| Parity | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) |

| Hb (g/L) | 130 (124-135) | 129 (126-135) | 132 (124-138) | 130 (125-136) |

| Iron-containing supplements being taken at baseline† | 22 (22.9) | 24 (26.7) | 17 (17.7) | 63 (22.3) |

| Known hemoglobinopathy trait | 3 (3.1) | 4 (4.0) | 4 (3.9) | 11 (3.7) |

| Previous anemia | ||||

| Outside of pregnancy | 12 (12.2) | 6 (6.1) | 12 (11.7) | 30 (10.0) |

| During pregnancy | 5 (5.1) | 7 (7.1) | 10 (9.7) | 22 (7.3) |

| Both | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Comorbidity‡ | 9 (9.2) | 11 (11.1) | 18 (17.5) | 38 (12.7) |

| At least 1 previous termination | 12 (12.2) | 13 (13.1) | 14 (13.6) | 39 (13.0) |

| At least 1 previous miscarriage or still birth | 30 (30.6) | 27 (27.3) | 32 (31.1) | 89 (29.7) |

| At least 1 previous postpartum hemorrhage (>1/L) | 3 (3.1) | 7 (7.1) | 11 (10.7) | 21 (7.0) |

BMI, body mass index, Q, quartile.

Estimated using the participant’s postcode to determine their Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) (2019). IMD data were not recorded for 108 participants because consent was not obtained to collect their postcode.

There were 17 participants for whom baseline medication was indicated but it is unknown whether it contained iron. In total, of those who took iron supplements at baseline, 41 (65%) were still taking them at the end of the study.

Including hypertension, cardiac disease, thyroid disorders, renal disease, preexisting diabetes, clotting disorders, and anticoagulant therapy. There were 2 missing Hb values for participants at the baseline assessment. The data are presented as number (percentage) for categorical variables and median (Q1-Q3) for continuous variables.

Adherence outcomes

Tablet return data were complete for 228 of the 300 (76%) participants, and MEMS data completeness was 75% (102 of 137 MEMS caps were returned). Based on tablet count, 130 of the 228 participants (57.0%; 95% CI, 50.3-63.5) were adherent (they returned the expected number of tablets ±15%). This rate was lowest in the daily arm and similar for the alternate and 3 times a week arms (Table 3); however, the CIs for the rates overlapped for all 3 arms. The mean proportion of tablets taken as expected per participant was 82.5% overall (72.3%, 89.6%, and 84.5% for the daily, alternate, and 3 times a week arm, respectively). The main reasons that participants reported not taking their tablets as planned were because of forgetting or because of side effects (supplemental Table 9). There were 20 participants who had at least 1 dose reduction reported with 9 of those in the daily arm, 7 in the alternate arm, and 4 in the 3 times a week arm.

Adherence to oral iron supplement by arm

| . | Daily (n = 98) . | Alternate (n = 99) . | Three times a week (n = 103) . | Total (N = 300) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tablet count | ||||

| Mean (SD) number of tablets taken per wk | 5.1 (2.1) | 3.1 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.2) | 3.5 (2.0) |

| Number (%) of participants considered to be adherent based on tablet return | 33/70 (47.1) | 49/79 (62.0) | 48/79 (60.8) | 130/228 (57.0) |

| 95% CI for proportion | (35.1-59.4) | (50.4-72.7) | (49.1-71.6) | (50.3-63.5) |

| Mean (SD) proportion of tablets taken as expected per participant | 72.3 (31.3) | 89.6 (46.1) | 84.5 (40.3) | 82.5 (40.5) |

| MARS-5 | ||||

| Number (%) of participants with completed MARS-5 questionnaire | 72/98 (73.5) | 80/99 (80.8) | 83/103 (80.6) | 235/300 (78.3) |

| Minimum MARS-5 score | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 |

| Median (IQR) MARS-5 score | 23 (21-24) | 24 (22-24) | 24 (22-25) | 24 (22-24) |

| Mean (SD) MARS-5 score | 21.7 (3.8) | 22.4 (3.5) | 22.7 (3.3) | 22.3 (3.6) |

| Maximum MARS-5 score | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| MEMS | ||||

| Number (%) of participants randomized to a MEMS cap | 50/98 (51.0) | 43/99 (43.4) | 52/103 (50.5) | 145/300 (48.3) |

| Number (%) of participants with a MEMS cap | 48/50 (96.0) | 40/43 (93.0) | 49/52 (94.2) | 137/145 (94.5) |

| Number (%) MEMS data complete | 36/48 (75.0) | 28/40 (70.0) | 38/49 (77.6) | 102/137 (74.5) |

| Number (%) of participants considered to be adherent based on PDC MEMS data | 15/36 (41.7) | 12/28 (42.9) | 13/38 (34.2) | 40/102 (39.2) |

| MEMS data: mean (SD) proportion of days (PDC), per participant, when the doses taken were | ||||

| As expected | 72.1 (25.5) | 64.5 (34.3) | 65.7 (29.8) | 67.6 (29.6) |

| Less than expected | 26.7 (25.4) | 30.3 (33.7) | 29.9 (31.3) | 28.9 (29.8) |

| More than expected | 1.3 (1.7) | 5.2 (14.6) | 4.4 (5.6) | 3.5 (8.5) |

| . | Daily (n = 98) . | Alternate (n = 99) . | Three times a week (n = 103) . | Total (N = 300) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tablet count | ||||

| Mean (SD) number of tablets taken per wk | 5.1 (2.1) | 3.1 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.2) | 3.5 (2.0) |

| Number (%) of participants considered to be adherent based on tablet return | 33/70 (47.1) | 49/79 (62.0) | 48/79 (60.8) | 130/228 (57.0) |

| 95% CI for proportion | (35.1-59.4) | (50.4-72.7) | (49.1-71.6) | (50.3-63.5) |

| Mean (SD) proportion of tablets taken as expected per participant | 72.3 (31.3) | 89.6 (46.1) | 84.5 (40.3) | 82.5 (40.5) |

| MARS-5 | ||||

| Number (%) of participants with completed MARS-5 questionnaire | 72/98 (73.5) | 80/99 (80.8) | 83/103 (80.6) | 235/300 (78.3) |

| Minimum MARS-5 score | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 |

| Median (IQR) MARS-5 score | 23 (21-24) | 24 (22-24) | 24 (22-25) | 24 (22-24) |

| Mean (SD) MARS-5 score | 21.7 (3.8) | 22.4 (3.5) | 22.7 (3.3) | 22.3 (3.6) |

| Maximum MARS-5 score | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| MEMS | ||||

| Number (%) of participants randomized to a MEMS cap | 50/98 (51.0) | 43/99 (43.4) | 52/103 (50.5) | 145/300 (48.3) |

| Number (%) of participants with a MEMS cap | 48/50 (96.0) | 40/43 (93.0) | 49/52 (94.2) | 137/145 (94.5) |

| Number (%) MEMS data complete | 36/48 (75.0) | 28/40 (70.0) | 38/49 (77.6) | 102/137 (74.5) |

| Number (%) of participants considered to be adherent based on PDC MEMS data | 15/36 (41.7) | 12/28 (42.9) | 13/38 (34.2) | 40/102 (39.2) |

| MEMS data: mean (SD) proportion of days (PDC), per participant, when the doses taken were | ||||

| As expected | 72.1 (25.5) | 64.5 (34.3) | 65.7 (29.8) | 67.6 (29.6) |

| Less than expected | 26.7 (25.4) | 30.3 (33.7) | 29.9 (31.3) | 28.9 (29.8) |

| More than expected | 1.3 (1.7) | 5.2 (14.6) | 4.4 (5.6) | 3.5 (8.5) |

IQR, interquartile range; PDC, percentage of days covered; SD, standard deviation.

We only recruited a subset of women to receive MEMS caps to provide additional detail for the main prespecified adherence measure of tablet count. Participants who received a MEMS cap did not have different adherence rates compared with those who did not (supplemental Table 5). Concurrence between the MEMS data and tablet count adherence indicator was 79% overall. When the indicators did not agree, this was because the MEMS data indicated nonadherence when the tablet count indicated adherence; this was more common in the 3 times a week arm (supplemental Table 5). MEMS data facilitated the assessment of adherence over time and indicated that adherence was better earlier in the trial, particularly for the daily arm (supplemental Figure 1). Overall, the reported MARS-5 medial adherence scores were calculated for 78% of participants and were high for the majority; the median score was 23 for the daily arm and 24 for both the alternate and 3 times a week arm (max score = 25; Table 3).

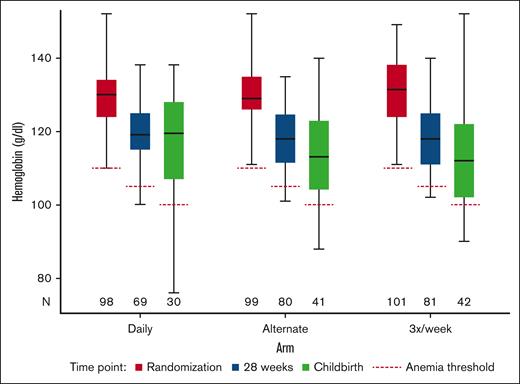

Maternal Hb

The data for the maintenance of maternal Hb outcome were calculated using Hb reported at randomization and at 28 weeks’ gestation for 230 participants (Figure 2; supplemental Table 6). A reduction in Hb between randomization and 28 weeks’ gestation seemed smaller for the daily arm with an adjusted mean difference of 10.9 g/L (95% CI, 9.2-12.7) than 12.3 g/L (95% CI, 10.8-13.9) for the alternate arm and 12.4 g/L (95% CI, 10.8-14.0) for the 3 times a week arm. However, the CIs for the differences overlapped for all 3 arms. Overall, 94% of the participants maintained their Hb levels above the diagnostic thresholds for anemia at 28 weeks; this was 95.7% (95% CI, 87.8-99.1) for the daily arm, 91.3% (95% CI, 82.8-96.4) for the alternate day arm, and 96.3% (95% CI, 89.6-99.2) for the 3 times a week arm.

Boxplot of Hb by visit and arm, including diagnostic anemia thresholds.

Side effects

The rates of a range of side effects often considered to be related to iron use varied across the arms and across the visits, but it should be noted that all except black stools were commonly reported at baseline (supplemental Table 7; supplemental Figures 2-6). Black stools were most commonly reported in the daily arm at rates above 50% between 16 and 24 weeks’ gestation (at 16 weeks, 54.3% reported black stools in the daily arm as opposed to 34.1% in the alternate day arm and 35.6% in the 3 times a week arm). Constipation was the second most reported side effect and again was more common in the daily arm (at 16 weeks, 49.4% reported constipation in the daily compared with 35.6% and 36.0% in the alternate day and 3 times a week arm, respectively). Nausea was more common overall in the earlier visits and most frequent in the daily arm at 16 weeks. Heartburn (from 24 weeks’ gestation) and indigestion were more common in the alternate day arm; indigestion was reported by 29.3% in the alternate arm at 24 weeks’ gestation as opposed to by 17.8% and by 24.1% in the daily arm and 3 times a week arm, respectively. Heartburn was reported by 54.1% in the alternate arm at 24 weeks’ gestation compared with 40.5% and 45.1% in the daily arm and 3 times a week arm, respectively. Overlap in the CIs for the proportions of participants who reported the symptoms was found for each symptom when the arms were compared at each time point.

Other outcomes

Infant and maternal outcome data for all participants for whom delivery data were reported included the birth weight, gestational age, estimated blood loss, mode of delivery, and infant feeding (Table 4). Pregnancy outcome data were complete for 273 (91%) of the randomized participants. These outcomes were exploratory and designed to test the level of data acquisition for further clinical studies. Ascertainment of outcome data was high in all 3 arms with more than 95% completeness in all categories. For those participants who reached the childbirth visit, data completeness was 98%.

Infant and maternal outcomes at delivery by arm

| . | Daily . | Alternate . | Three times a week . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy outcome, n/N (%) | ||||

| Livebirth | 83/86 (96.5) | 93/95 (97.9) | 91/92 (98.9) | 267/273 (97.8) |

| Miscarriage (defined as spontaneous loss of pregnancy before 24 wk) | 1/86 (1.2) | 1/95 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2/273 (0.7) |

| Termination of pregnancy | 1/86 (1.2) | 0/95 (0.0) | 1/92 (1.1) | 2/273 (0.7) |

| Stillbirth (defined as birth of baby on or after 24 wk gestation with no signs of life) | 1/86 (1.2) | 1/95 (1.1) | 0/92 (0.0) | 2/273 (0.7) |

| Birth weight (g) | ||||

| No. reported | 84 | 94 | 91 | 269 |

| Median (IQR) | 3355 (3040-3630) | 3355 (3024-3670) | 3410 (3075-3738) | 3372 (3060-3682) |

| Range | 970-4770 | 1595-4404 | 1450-4540 | 970-4770 |

| Gestational age (wk) | ||||

| No. reported | 82 | 91 | 90 | 263 |

| Median (IQR) | 39.8 (39.1-40.6) | 39.4 (38.6-40.3) | 39.3 (38.6-40.3) | 39.4 (38.7-40.3) |

| Range | 32-42 | 31.9-41.9 | 34.0-42.4 | 31.9-42.4 |

| Infant sex, n/N (%) | ||||

| Male | 39/86 (45.3) | 48/95 (50.5) | 44/92 (47.8) | 131/273 (48.0) |

| Female | 45/86 (52.3) | 46/95 (48.4) | 47/92 (51.1) | 138/273 (50.5) |

| Missing | 2/86 (2.3) | 1/95 (1.1) | 1/92 (1.1) | 4/273 (1.5) |

| Mode of infant care immediately after delivery, n/N (%) | ||||

| With mother, normal care | 80/86 (93.0) | 89/95 (93.7) | 82/92 (89.1) | 251/273 (91.9) |

| Transitional care | 1/86 (1.2) | 1/95 (1.1) | 2/92 (2.2) | 4/273 (1.5) |

| Special care | 1/86 (1.2) | 1/95 (1.1) | 4/92 (4.3) | 6/273 (2.2) |

| High-dependency care | 1/86 (1.2) | 2/95 (2.1) | 3/92 (3.3) | 6/273 (2.2) |

| Intensive care | 1/86 (1.2) | 0/95 (0.0) | 0/92 (0.0) | 1/273 (0.4) |

| Missing | 2/86 (2.3) | 2/95 (2.1) | 1/92 (1.1) | 5/273 (1.8) |

| Estimated maternal blood loss (mL) | ||||

| No. reported | 86 | 95 | 91 | 272 |

| Median (IQR) | 400 (200-650) | 400 (300-610) | 450 (300-700) | 400 (300-650) |

| Categorical summary, n/N (%) | ||||

| <500 mL | 50/86 (58.1) | 55/95 (57.9) | 48/91 (52.7) | 153/272 (56.3) |

| 500-999 mL | 27/86 (31.4) | 33/95 (34.7) | 32/91 (35.2) | 92/272 (33.8) |

| 1000-1499 mL | 4/86 (4.7) | 4/95 (4.2) | 4/91 (4.4) | 12/272 (4.4) |

| ≥1500 mL | 5/86 (5.8) | 3/95 (3.2) | 7/91 (7.7) | 15/272 (5.5) |

| Maternal prescription of treatment iron, n/N (%) | ||||

| Between week 28 and delivery | 6/55 (10.9) | 5/60 (8.3) | 10/58 (17.2) | 21/173 (12.1) |

| Prescription of oral iron after the birth | 14/86 (16.3) | 14/95 (14.7) | 21/91 (23.1) | 49/272 (18.0) |

| Intravenous iron infusion before discharge | 3/86 (3.5) | 0/95 (0.0) | 0/91 (0.0) | 3/272 (1.1) |

| Breastfeeding status at discharge from maternity care, n/N (%) | ||||

| Exclusively breastfeeding | 41/86 (47.7) | 51/95 (53.7) | 52/92 (56.5) | 144/273 (52.7) |

| Mixed feeding (breast and formula milk) | 14/86 (16.3) | 16/95 (16.8) | 10/92 (10.9) | 40/273 (14.7) |

| Only formula milk | 27/86 (31.4) | 25/95 (26.3) | 29/92 (31.5) | 81/273 (29.7) |

| Missing | 4/86 (4.7) | 3/95 (3.2) | 1/92 (1.1) | 8/273 (2.9) |

| Type of labor, n/N (%) | ||||

| Spontaneous | 36/86 (41.9) | 47/95 (49.5) | 34/92 (37.0) | 117/273 (42.9) |

| Induced | 44/86 (51.2) | 37/95 (38.9) | 43/92 (46.7) | 124/273 (45.4) |

| Missing | 6/86 (7.0) | 11/95 (11.6) | 15/92 (16.3) | 32/273 (11.7) |

| Mode of delivery, n/N (%) | ||||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 46/86 (53.5) | 50/95 (52.6) | 33/92 (35.9) | 129/273 (47.3) |

| Emergency cesarean delivery | 14/86 (16.3) | 16/95 (16.8) | 16/92 (17.4) | 46/273 (16.8) |

| Elective cesarean delivery | 9/86 (10.5) | 16/95 (16.8) | 24/92 (26.1) | 49/273 (17.9) |

| Assisted vaginal delivery | 17/86 (19.8) | 13/95 (13.7) | 18/92 (19.6) | 48/273 (17.6) |

| Missing | 0/86 (0.0) | 0/95 (0.0) | 1/92 (1.1) | 1/273 (0.4) |

| PPH, n/N (%) | ||||

| Cause of PPH | 20/86 (23.3) | 16/95 (16.8) | 21/90 (23.3) | 57/271 (21.0) |

| Atonic uterus | 3/20 (15.0) | 2/16 (12.5) | 7/21 (33.3) | 12/57 (21.1) |

| Retained placenta | 1/20 (5.0) | 0/16 (0.0) | 1/21 (4.8) | 2/57 (3.5) |

| Placental fragments | 1/20 (5.0) | 1/16 (6.3) | 0/21 (0.0) | 2/57 (3.5) |

| Trauma | 14/20 (70.0) | 9/16 (56.3) | 11/21 (52.4) | 34/57 (59.6) |

| Cause missing | 1/20 (5.0) | 4/16 (25.0) | 2/21 (9.5) | 7/57 (12.3) |

| Mother admitted to higher level of care, n/N (%) | ||||

| Type of higher level of care | 0/86 (0.0) | 6/95 (6.3) | 4/91 (4.4) | 10/272 (3.7) |

| Enhanced maternity care | - | 3/6 (50.0) | 1/4 (25.0) | 4/10 (40.0) |

| High-dependency unit (level 2) | - | 3/6 (50.0) | 2/4 (50.0) | 5/10 (50.0) |

| Intensive treatment unit (level 3) | - | 0/6 (0.0) | 1/4 (25.0) | 1/10 (10.0) |

| . | Daily . | Alternate . | Three times a week . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy outcome, n/N (%) | ||||

| Livebirth | 83/86 (96.5) | 93/95 (97.9) | 91/92 (98.9) | 267/273 (97.8) |

| Miscarriage (defined as spontaneous loss of pregnancy before 24 wk) | 1/86 (1.2) | 1/95 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2/273 (0.7) |

| Termination of pregnancy | 1/86 (1.2) | 0/95 (0.0) | 1/92 (1.1) | 2/273 (0.7) |

| Stillbirth (defined as birth of baby on or after 24 wk gestation with no signs of life) | 1/86 (1.2) | 1/95 (1.1) | 0/92 (0.0) | 2/273 (0.7) |

| Birth weight (g) | ||||

| No. reported | 84 | 94 | 91 | 269 |

| Median (IQR) | 3355 (3040-3630) | 3355 (3024-3670) | 3410 (3075-3738) | 3372 (3060-3682) |

| Range | 970-4770 | 1595-4404 | 1450-4540 | 970-4770 |

| Gestational age (wk) | ||||

| No. reported | 82 | 91 | 90 | 263 |

| Median (IQR) | 39.8 (39.1-40.6) | 39.4 (38.6-40.3) | 39.3 (38.6-40.3) | 39.4 (38.7-40.3) |

| Range | 32-42 | 31.9-41.9 | 34.0-42.4 | 31.9-42.4 |

| Infant sex, n/N (%) | ||||

| Male | 39/86 (45.3) | 48/95 (50.5) | 44/92 (47.8) | 131/273 (48.0) |

| Female | 45/86 (52.3) | 46/95 (48.4) | 47/92 (51.1) | 138/273 (50.5) |

| Missing | 2/86 (2.3) | 1/95 (1.1) | 1/92 (1.1) | 4/273 (1.5) |

| Mode of infant care immediately after delivery, n/N (%) | ||||

| With mother, normal care | 80/86 (93.0) | 89/95 (93.7) | 82/92 (89.1) | 251/273 (91.9) |

| Transitional care | 1/86 (1.2) | 1/95 (1.1) | 2/92 (2.2) | 4/273 (1.5) |

| Special care | 1/86 (1.2) | 1/95 (1.1) | 4/92 (4.3) | 6/273 (2.2) |

| High-dependency care | 1/86 (1.2) | 2/95 (2.1) | 3/92 (3.3) | 6/273 (2.2) |

| Intensive care | 1/86 (1.2) | 0/95 (0.0) | 0/92 (0.0) | 1/273 (0.4) |

| Missing | 2/86 (2.3) | 2/95 (2.1) | 1/92 (1.1) | 5/273 (1.8) |

| Estimated maternal blood loss (mL) | ||||

| No. reported | 86 | 95 | 91 | 272 |

| Median (IQR) | 400 (200-650) | 400 (300-610) | 450 (300-700) | 400 (300-650) |

| Categorical summary, n/N (%) | ||||

| <500 mL | 50/86 (58.1) | 55/95 (57.9) | 48/91 (52.7) | 153/272 (56.3) |

| 500-999 mL | 27/86 (31.4) | 33/95 (34.7) | 32/91 (35.2) | 92/272 (33.8) |

| 1000-1499 mL | 4/86 (4.7) | 4/95 (4.2) | 4/91 (4.4) | 12/272 (4.4) |

| ≥1500 mL | 5/86 (5.8) | 3/95 (3.2) | 7/91 (7.7) | 15/272 (5.5) |

| Maternal prescription of treatment iron, n/N (%) | ||||

| Between week 28 and delivery | 6/55 (10.9) | 5/60 (8.3) | 10/58 (17.2) | 21/173 (12.1) |

| Prescription of oral iron after the birth | 14/86 (16.3) | 14/95 (14.7) | 21/91 (23.1) | 49/272 (18.0) |

| Intravenous iron infusion before discharge | 3/86 (3.5) | 0/95 (0.0) | 0/91 (0.0) | 3/272 (1.1) |

| Breastfeeding status at discharge from maternity care, n/N (%) | ||||

| Exclusively breastfeeding | 41/86 (47.7) | 51/95 (53.7) | 52/92 (56.5) | 144/273 (52.7) |

| Mixed feeding (breast and formula milk) | 14/86 (16.3) | 16/95 (16.8) | 10/92 (10.9) | 40/273 (14.7) |

| Only formula milk | 27/86 (31.4) | 25/95 (26.3) | 29/92 (31.5) | 81/273 (29.7) |

| Missing | 4/86 (4.7) | 3/95 (3.2) | 1/92 (1.1) | 8/273 (2.9) |

| Type of labor, n/N (%) | ||||

| Spontaneous | 36/86 (41.9) | 47/95 (49.5) | 34/92 (37.0) | 117/273 (42.9) |

| Induced | 44/86 (51.2) | 37/95 (38.9) | 43/92 (46.7) | 124/273 (45.4) |

| Missing | 6/86 (7.0) | 11/95 (11.6) | 15/92 (16.3) | 32/273 (11.7) |

| Mode of delivery, n/N (%) | ||||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 46/86 (53.5) | 50/95 (52.6) | 33/92 (35.9) | 129/273 (47.3) |

| Emergency cesarean delivery | 14/86 (16.3) | 16/95 (16.8) | 16/92 (17.4) | 46/273 (16.8) |

| Elective cesarean delivery | 9/86 (10.5) | 16/95 (16.8) | 24/92 (26.1) | 49/273 (17.9) |

| Assisted vaginal delivery | 17/86 (19.8) | 13/95 (13.7) | 18/92 (19.6) | 48/273 (17.6) |

| Missing | 0/86 (0.0) | 0/95 (0.0) | 1/92 (1.1) | 1/273 (0.4) |

| PPH, n/N (%) | ||||

| Cause of PPH | 20/86 (23.3) | 16/95 (16.8) | 21/90 (23.3) | 57/271 (21.0) |

| Atonic uterus | 3/20 (15.0) | 2/16 (12.5) | 7/21 (33.3) | 12/57 (21.1) |

| Retained placenta | 1/20 (5.0) | 0/16 (0.0) | 1/21 (4.8) | 2/57 (3.5) |

| Placental fragments | 1/20 (5.0) | 1/16 (6.3) | 0/21 (0.0) | 2/57 (3.5) |

| Trauma | 14/20 (70.0) | 9/16 (56.3) | 11/21 (52.4) | 34/57 (59.6) |

| Cause missing | 1/20 (5.0) | 4/16 (25.0) | 2/21 (9.5) | 7/57 (12.3) |

| Mother admitted to higher level of care, n/N (%) | ||||

| Type of higher level of care | 0/86 (0.0) | 6/95 (6.3) | 4/91 (4.4) | 10/272 (3.7) |

| Enhanced maternity care | - | 3/6 (50.0) | 1/4 (25.0) | 4/10 (40.0) |

| High-dependency unit (level 2) | - | 3/6 (50.0) | 2/4 (50.0) | 5/10 (50.0) |

| Intensive treatment unit (level 3) | - | 0/6 (0.0) | 1/4 (25.0) | 1/10 (10.0) |

Note that participants who have fully withdrawn or have been lost to follow-up before the delivery visit were excluded from this table (unless delivery data have been reported from patient notes for those lost to follow-up).

IQR, interquartile range; PPH, postpartum hemorrhage.

Discussion

We successfully conducted a pilot randomized trial of 3 different doses of oral iron supplementation that started in the first trimester of pregnancy at ≤13 weeks plus 6 days of gestation. Our study was supported by a very active PPI program. Difficulties with compliance to prescribed oral iron are commonly described by women during antenatal care, and this was confirmed in our study; just under half of all participants forgot some tablets or made changes to their medication at some stage. The most commonly stated reason for incomplete adherence was side effects, such as nausea or heartburn. However, these features are also part of the common symptomatology that otherwise healthy women experience repeatedly and regularly during pregnancy, and it is difficult to definitively attribute such side effects to the iron supplementation. Indeed, many of these symptoms were recorded at baseline in our trial before the allocated iron tablets were administered.

Overall, adherence rates seemed to be slightly lower in the daily iron arm with higher rates of side effects. The results indicated a lower adherence rate in the daily arm (47%) when compared with the alternate days (62%) and 3 times a week (61%) arms, although our chosen primary measure for adherence (a tablet count with a ±15% variance) was exacting. Considering other adherence measures, the mean proportion of tablets taken as expected was 72.3% in the daily arm, 89.6% for the alternate days arm, and 84.5% for the 3 times a week arm. Translating that into the number of tablets received each week gave a mean of 5.1 iron tablets in the daily arm, 3.1 for alternate days and 2.6 for the 3 times a week arm. The participants in the daily arm were therefore, over a period of a week, getting the most iron. The 2 main reasons for the lack of adherence in our study were side effects and forgetting to take the tablets. However, the proportions for each reason changed with advancing gestation; a lack of adherence because of side effects became less common over the pregnancy, whereas forgetting to take the tablets became more common such that by 28 weeks’ gestation it was the principal reason for not taking tablets on time.

Although high levels of adherence are desired for iron supplementation (and indeed any medication in pregnancy), levels approaching 100% are unlikely to be attained. There is a need for prescribers of iron to consider an acceptable level of adherence for an acceptable dosage of drug that will enable a therapeutic effect to occur. Increasing the dose of a drug without considering the side effects may adversely reduce adherence. Based on previous evidence32 and our formative research, we developed an intervention to support medication adherence that was piloted among a subset of participants in this trial, and we have conducted a parallel process evaluation to explore the acceptability of oral iron supplements for the prevention of anemia and the factors that influenced adherence. It was not an aim of the trial to assess any impact on adherence using the medication adherence intervention, and the trial was not powered for this. A post hoc sensitivity analysis of tablet count adherence in the 240 participants who did not receive the adherence intervention showed that the proportion considered adherent was similar to the overall results (54.8% vs 57.0%, respectively).

We examined 5 main potential side effects of iron supplementation in our study, namely nausea, vomiting, heartburn, indigestion, and constipation, and 1 specific effect directly associated with the ingestion of oral iron, namely black stools. Black stools are an indication that not all the iron is being absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and were more commonly reported in the daily iron arm but it did occur in the other arms of the trial for many participants. The pattern and frequency of side effects also changed across gestation. For example, nausea was most frequent in early pregnancy and improved with time, whereas heartburn worsened. Overall, the symptoms improved as pregnancy progressed and the frequency with which iron was taken seemed to make little or no difference to either the frequency or intensity of most of the symptoms.

The Hb concentrations seemed slightly higher in the daily iron arm, as might be expected given that there was a higher weekly dose of iron administered, but the CIs for the Hb levels indicated no statistical difference between the arms. Infant clinical outcomes, including deaths, preterm births, small for gestational age seemed equally uncommon across all study arms. In our study, around 1 in 5 participants still experienced varying degrees of postpartum hemorrhage. Further study is required to assess any relationship with preexisting antenatal anemia.33,34 If confirmed, added blood loss might be expected to further exacerbate the already low maternal stores of iron, including the women without anemia with a borderline iron status, reinforcing the pressing need to better address the public health issue of anemia in pregnancy.

The strengths of this study were engagement with the women and health care professionals, which delivered a study with consent rates of above 40% of participants screened and with high rates of follow-up for outcome data collection. We accounted for hemodilution as pregnancy advanced by investigating the fall in Hb across each arm of the trial. Limitations to our study should be recognized. The use of a placebo would have more clearly established the relative effects of iron supplementation vs those of pregnancy but would have added to the trial complexity. We did not exclude women who took over-the-counter supplements that might have included iron (and potential inhibitors of absorption such as calcium), although in a sensitivity analysis, there did not seem to be a difference in the adherence rates or the Hb levels of those who were taking the supplements and those who were not (supplemental Tables 12 and 13). There were variable levels of adherence, as discussed previously, although we may have set a level of adherence that was too restrictive in light of the subsequent reconsideration of what might be required for a therapeutic effect. Dose modifications occurred in our study, although the overall numbers were small.

Our trial supports the need for a definitive trial to establish the clinical benefits of a prophylactic policy of oral iron supplementation in pregnancy.35,36 We successfully recruited women without anemia across 5 NHS Trusts and collected data for a range of clinical outcomes that were prioritized by women to be highly relevant with high levels of ascertainment. Overall, the outcomes were similar for the daily dose and alternate daily dose iron schedule, but the 3× weekly dose may have less efficacy, and the rates of adherence were lower. In explaining iron supplementation in clinical practice or future trials, women should be informed that many symptoms often considered to be related to oral iron supplementation are commonly seen in pregnancy and may improve as the pregnancy progresses. The trial results and the progression criteria for fidelity, adherence, and recruitment (supplemental Figure 10) were reviewed by an independent external panel that was initially blinded to oral iron schedule allocation, which provided a report to the researchers. The panel considered that there was no clear advantage between the daily and alternate day iron regimens. Overall, we propose that a daily dosing schedule may provide the best opportunity to deliver an adequate iron load to cope with the increasing demands of the mother, the fetus, and the placenta in the late third trimester and to replace any iron deficit in women without anemia with a greater potential clinical benefit. A protocol for a pragmatic definitive trial has been informed by the design and results of the pilot trial (ISRCTN164255).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants in this trial and Helen Thomas, Matthew Wiblin, Catherine Bain, Nkechi Onwuka, Claire Dyer, Alison Deary, and Valerie Hopkins (Clinical Trials Unit), members of the Nottingham Maternity Research Network, the external Data Monitoring Committee, and the Trial Steering Committee for their contributions. The authors acknowledge the helpful input from the international review panel chaired by Sant-Rayn Pasricha.

The trial is funded by the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (NIHR200869). AF is supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203311). MK is an NIHR Senior Investigator (NIHR303806). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The trial sponsors and funders had no role in the study design, analyses, interpretation of data, writing, and decision to publish.

Authorship

Contribution: S.J.S., M.K., and D.C. conceived the study; S.J.S., D.C., and S.S. developed the initial protocol; all authors contributed to the complete protocol, study activities, and data collection; C.H. and R.B. wrote the statistical analysis plan and performed the statistical analysis; S.S. and D.C. wrote the first draft; all authors revised and approved the manuscript; all authors had full access to all data in the study and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication; S.J.S. was responsible for the final data analysis and data integrity.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the PANDA Collaborator Group appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Simon J. Stanworth, National Health Service Blood and Transplant and Oxford University Hospitals National Health Service Foundation Trust, Level 2, John Radcliffe Hospital, Headley Way, Headington, Oxford, OX3 9BQ, United Kingdom; email: simon.stanworth@nhsbt.nhs.uk.

Appendix

The clinical study site collaborators are John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom (Principal Investigator: Jane Hirst; Midwife: Jude Mossop); Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading (Principal Investigator: Sarah Philip; Midwives: Anna Campbell; Emma Gammin); New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton, United Kingdom (Principal Investigator: David Churchill; Midwife: Ellmina McKenzie; South Tyneside District Hospital, South Shields & Sunderland Royal Hospital, Sunderland, United Kingdom (Principal Investigator: current: Rachel Nicholson; previously: Kim Hinshaw; Midwives: Judith Ormonde & Lesley Hewitt; Royal London Hospital, London & Whipps Cross Hospital, London, United Kingdom (Principal Investigator: Stamatina Iliodromiti; Midwives: Amy Thomas; Prudence Jones).

References

Author notes

S.J.S. and D.C. are joint first authors.

Deidentified participant data and the study protocol will be available upon request to the National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) Clinical Trials Unit, after deidentification (text, tables, figures and appendixes), 9 months after publication and ending 5 years after article publication. Data will be shared with investigators whose use of the data has been assessed and approved by an NHSBT review committee as a methodologically sound proposal.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.