Visual Abstract

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)–based gene therapy is an emerging treatment for hemophilia A (HA) and hemophilia B (HB). In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched for studies of adult males with severe or moderately severe HA or HB who received AAV-based gene therapy. Annualized bleeding rate (ABR), annualized infusion rate (AIR), total factor use, factor levels, and adverse events (AEs) were extracted. Eight HA trials representing 7 gene therapies and 211 patients and 12 HB trials representing 9 gene therapies and 184 patients were included. For HA, gene therapy resulted in an annualized decrease of 7.58 bleeding events (95% confidence interval [CI], −11.50 to −3.67) and 117.2 factor infusions (95% CI, −151.86 to −82.53) compared with before gene therapy. Factor VIII level at 12 months ranged from 10.4 to 70.31 IU/mL by 1-stage assay. HB gene therapies were associated with an annualized decrease of 5.64 bleeding events (95% CI, −8.61 to −2.68) and 58.92 factor infusions (95% CI, −68.19 to −49.65). Mean factor IX level at 12 months was 28.72 IU/mL (95% CI, 18.78-38.66). Factor expression was more durable for HB than HA; factor IX levels remained at 95.7% of their peak whereas factor VIII levels fell to 55.8% of their peak at 24 months. The pooled percentage of patients experiencing a serious AE was 19% (10%-31%) and 21% (10%-37%) for HA and HB gene therapies, respectively. No thrombosis or inhibitor formation was reported. AAV-based gene therapies for both HA and HB demonstrated significant reductions in ABR, AIR, and factor use.

Introduction

Hemophilia A and B (HA and HB, respectively) are inherited X-linked bleeding disorders, characterized by deficiency of factor VIII (FVIII) and FIX, respectively. Hemophilia affect >1.2 million individuals worldwide, with HA being more common than HB.1 Hemophilia primarily affects males, although females can also be affected. Disease severity is characterized by factor level. Severe hemophilia is defined as <1% factor activity, moderate hemophilia as factor activity level ≥1% to ≤5% of normal, and mild hemophilia as factor activity level of >5% to <40% of normal.2 About one-half to two-thirds of patients with HA and approximately one-third to one-half of patients with HB have severe disease.1,3 Patients with severe hemophilia are prone to spontaneous and recurrent bleeding events, most commonly into joints, which can lead to severe degenerative arthropathy over time.

Prophylactic clotting factor replacement has been used for decades to prevent or mitigate bleeding events and hemophilic arthropathy. More recently, subcutaneously administered nonfactor therapies have expanded treatment options for patients.4,5 However, both factor prophylaxis and subcutaneous therapies are costly, require regular administration, and do not fully correct hemostasis, thereby exposing patients to a risk of breakthrough bleeding and the need for intensification of therapy for surgery.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)–based gene therapy has emerged as a novel treatment strategy aimed at overcoming these limitations. It introduces an AAV vector that inserts a functional copy of the missing clotting factor gene into patients’ hepatocytes so that clotting factor can be expressed.5,6 Valoctocogene roxaparvovec was approved as the first gene therapy for HA in the United States in June 2023.7 Etranacogene dezaparvovec and fidanacogene elaparvovec were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in November 2022 and April 2024, respectively, for adults with HB. Several other gene therapies are under various stages of development.8,9 Although these therapies appear to have few serious adverse events (AEs), a notable toxicity of hepatotropic AAV-based gene therapy is liver toxicity, which can result in loss of transgene expression of factor.6-8

Given the rapid advancements and approvals in the field, it is essential to evaluate the overall impact of these therapies. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of AAV-based gene therapies for HA and HB to summarize the efficacy and safety of this emerging therapeutic class.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

We electronically searched 4 databases (the Cochrane Library, Embase, PubMed, and Scopus) from database inception to 26 May 2024. A search strategy and relevant keywords were determined in consultation with a health sciences librarian. Search terms were focused on HA and HB as well as gene therapy. A full search strategy is available in supplemental Methods. Conference proceedings from 2013 through 2023 (inclusive) from the annual meetings of the American Society of Hematology, International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis, and European Hematology Association were hand-searched.

We included human studies on adult males with severe or moderately severe HA or HB (≤2% FVIII or FIX, respectively) who received AAV-based gene therapy targeting hepatocytes. We excluded case reports and series, editorials, and reviews.

Citations were imported into the data management system Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). Two investigators (S.R.D. and K.J.) independently completed title and abstract screening. Discrepancies were resolved with consensus discussion between these 2 investigators (S.R.D. and K.J.), and disagreements were arbitrated by a third investigator (A.C.). The same protocol was followed for the full-text review of citations that were included after title and abstract screening. References of included studies were scanned to identify further relevant studies.

Data extraction and risk-of-bias assessment

Because many included studies provided updated results for the same trial, references were grouped into clinical trials. For each included study, 2 investigators (S.R.D. and K.J.) independently extracted data using a standardized form with discrepancies resolved by consensus discussion between 4 investigators (S.R.D., K.J., A.C., and A.P.). Data extraction included trial identifiers, study design, location, inclusion and exclusion criteria, AAV vector, dose, patient demographics and characteristics, and study duration along with efficacy and safety outcomes. Outcomes were permitted to be derived from different references of the same trial. For all outcomes, we prioritized data completeness (eg, inclusion of mean and standard deviation rather than mean alone) over longer term follow-up. Our primary outcome was pooled mean difference (PMD) in total annualized bleeding rate (ABR) from the observational pre–gene therapy period to the post–gene therapy period. Secondary efficacy outcomes included PMD in mean annualized infusion rate (AIR; before therapy, after therapy), PMD in mean annualized use of factor concentrates (before therapy, after therapy), mean factor plasma levels at prespecified intervals (4 weeks, and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months) by 1-stage assay (OSA) and chromogenic substrate assay (CSA), ABR for joint and treated bleeds, and quality of life. For measurements at prespecified time points, we allowed for leeway of 1 week for measurements <1 month, 1 month for measurements between 1 month to 1 year, and 2 months for measurements ≥1 year from time of gene therapy administration. If not directly reported, ABR and AIR were derived with the following calculation: (number of events/number of days) × 365.25. Safety outcomes included AEs including serious AEs, infusion reactions, anaphylaxis, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevations, aminotransferase elevations requiring immunosuppression, inhibitor formation, and thrombosis events. When incomplete data were reported, ClinicalTrials.gov was queried for posted results, which were incorporated, provided the results had undergone review by the National Library of Medicine to ensure they met quality control standards. When summary data for an entire study population were not reported, we included data for distinct cohorts within the same trial.

For risk-of-bias assessment, we used the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies with No Control Group.12 Two investigators (S.R.D. and K.J.) independently appraised trial-level quality, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus discussion between them. Study quality was rated good (≤4 negative or missing assessment questions and low risk of bias), fair (5-6 negative or missing assessment questions), or poor (>6 negative or missing assessment questions or high risk of bias).

Data synthesis and analysis

Meta-analyses of the predefined efficacy and safety outcomes for HA and HB were performed. For HA, efficacy outcomes included ABR and AIR, whereas safety outcomes included the incidence of any AEs, serious AEs, and ALT elevation. For HB, efficacy outcomes additionally covered factor usage and factor levels at 12 months. Safety outcomes for HB mirrored those of HA. Efficacy outcomes were all continuous, presented as mean values both before and after gene therapy. Safety outcomes are reported as incidence rates after therapy.

Given intrinsic heterogeneity in these outcomes across studies, random-effects meta-analyses were used to derive the pooled point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Specifically, for the efficacy outcomes, pooled point estimates were obtained for the pretherapy and posttherapy mean differences. Studies lacking reported standard deviations for efficacy outcomes were included in the meta-analyses, with missing standard deviations imputed from the available data in the sample.13 For safety outcomes, the analyses provided pooled point estimates of the incidence rates after therapy.

Heterogeneity was quantified by Higgins and Thompson heterogeneity measure (I2)14 and tested using Cochran Q statistic,15 which examines the existence of statistically significant differences between subgroups. The values of I2 and Cochran Q test P values were reported. The heterogeneity measure I2 was calculated based on the weighted sum of the difference between the pooled estimate and the effect size (eg, mean difference) for each study. An I2 value of 0% to 25% represents nonsignificant heterogeneity, 26% to 50% represents low heterogeneity, 51% to 75% represents moderate heterogeneity, and >75% represents high heterogeneity. A Cochran Q test with a P value of <.05 indicates statistically significant heterogeneity between studies. For outcomes with significant heterogeneity, a sensitivity analysis was completed by removal of outlier results followed by repeat quantification of the heterogeneity measure I2. Outlier results were determined first by visual inspection of funnel plots and by absolute value of z score.

Potential publication bias was assessed through a funnel plot16 for visual inspection and the Egger test17 to evaluate asymmetry within the funnel plot. The results of the Egger test were reported alongside the funnel plot, with a P value of <.05 leading to rejection of the null hypothesis of symmetry in the funnel plot, indicating that there exists evidence suggesting the significant publication bias. A funnel plot displays the estimated point estimates (eg, mean difference, proportion) on the x-axis against the standard error of the estimated point estimates on the y-axis. The standard error on the y-axis was calculated based on reported standard deviations and sample sizes. All analyses were performed using the R package “meta” in R, version 4.2.1.

Results

Literature search

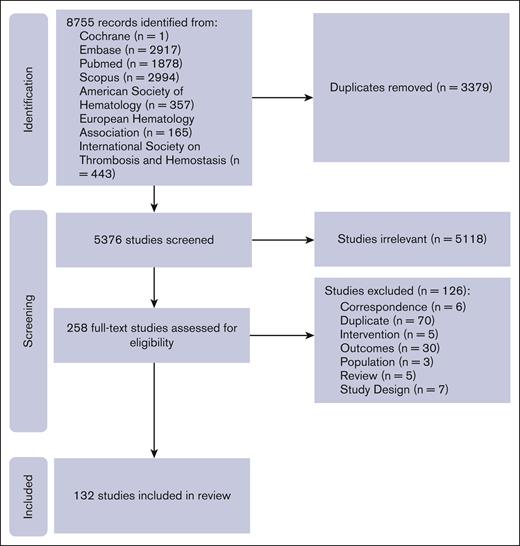

Of the 8755 citations identified, 8497 were excluded based on duplication or title and abstract screening, leaving 258 for full-text review. Of these, 132 publications met eligibility criteria.7,8,18-123 These references were grouped into 8 distinct trials, representing 7 gene therapies and 211 people with HA (PwHA), and 12 distinct trials representing 9 gene therapies and 184 people with HB (PwHB; supplemental Table 1). Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for study selection.

Trial flow for a systematic review of the literature on AAV-based gene therapy for HA and HB.

Trial flow for a systematic review of the literature on AAV-based gene therapy for HA and HB.

Study characteristics

Studies were primarily early phase trials (phase 1, n = 2; phase 2, n = 1; phase 1/2, n = 14), and 3 trials were phase 3.8,26,63 All phase 3 trials were single-arm, pre/post cohort studies. Twelve trials were multinational. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Trial name/NCT (phase) . | Gene therapy (prior names) . | Setting . | Design . | N∗ (n for individual dose cohorts) . | AAV vector . | Dose(s) (vg/kg) . | Age (y), mean (range) . | Non-White, % . | Duration (mo) . | Hemophilia severity (severe/moderately severe [%]) . | Time at which ABR measurement started . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | |||||||||||

| Alta/NCT03061201 (1/2) | Giroctocogene fitelparvovec (PF-07055480/SB-525) | United States | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 11 | AAV6 | 9e11, 2e12, 1e13, 3e13 | 30 (18-47) | 18.2 | 62 | 100/0 | Week 3 |

| GENEr8-1/NCT02576795 (1/2) | Valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN-270) | United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 13 (7, 6) | AAV5 | 6e13 4e13 | 30.4 (23-42) 31.3 (22-45) | 14.3 16.7 | 72 | 100/0 | Week 4 |

| GENEr8-1/NCT03370913 (3) | Valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN-270) | 13 countries† | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 134 | AAV5 | 6e13 | 31.7 (18-70) | 28.4 | 36 | 100/0 | Week 5 |

| NCT03003533/NCT03432520 (1/2) | Dirloctogene samoparvovec (SPK-8011) | 5 countries‡ | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 24 | AAV3 | 5e11 1e12 1.5e12 2e12 | 32.8 (18-52) | NR | 60 | 94.4/5.6 | Week 4 |

| NCT03734588 (1/2) | SPK-8016 | United States | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 4 | AAV-Spark | 5e11 | (18-63) | NR | 15 | 100/0 | NR |

| NCT03370172 (1/2) | TAK-754 | 8 countries§ | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 4 | AAV8 | 2e12 6e12 | (18-75) | NR | 10 | 100/0 | NR |

| NCT03588299 (1/2) | BAY 2599023 (AAVhu37.hFVIIIco) | 6 countries|| | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 9 | AAVhu37 | 5e12, 1e13, 2e13, 4e13 | NR | NR | 23 | 100/0 | NR |

| NCT03001830GO-8 (1/2) | GO-8 (AAV8-HLP-hFVIII-V3) | United States, United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 12 (1, 3, 3, 5) | AAV8 | 6e11, 2e12, 4e12, 6e12 | NR | NR | 60 | 100/0 | NR |

| HB | |||||||||||

| BENEGENE-2/NCT02484092 (1/2) | Fidanacogene elaparvovec (SPK-9001) | United States, Australia | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 15 | AAV-Spark100 | 5e11 | 35.6 (18-53) | 14.3 | 12 | 60/40 | Day 0 |

| BENEGENE-2/NCT03861273 (3) | Fidanacogene elaparvovec (SPK-9001) | 14 countries¶ | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 45 | AAV-Spark100 | 5e11 | 29 (18-62) | NR | 15 | NR | Week 12 |

| B-LIEVE/NCT05164471 (1/2) | Verbrinacogene setparvovec (FLT180a) | United States, United Kingdom | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 6 | AAVS3 | 7.7e11 | NR | NR | 12 | NR | NR |

| B-AMAZE/NCT03369444 (1/2) | Verbrinacogene setparvovec (FLT180a) | United States, Ireland, Italy, United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 10 (2, 2, 4, 2) | AAVS3 | 3.84e11, 6.4e11, 8.32e11, 1.28e12 | 37.2 (25-67) | 10 | 27.2 | 90/10 | Day 15 |

| NCT02396342 (1/2) | AMT-060 | Denmark, Germany, The Netherlands | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 10 (5, 5) | AAV5 | 5e12 2e13 | 69 (35-72) 35 (33-46) | 0 20 | 60 | 80/20 100/0 | NR |

| HOPE-B/NCT03569891 (2b) | Etranacogene dezaparvovec (AMT-061) | United States | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 3 | AAV5 | 2e13 | 46.7 (43-50) | 66.7 | 36 | 66.7/33.3 | Day 0 |

| HOPE-B/NCT03569891 (3) | Etranacogene dezaparvovec (AMT-061) | 8 countries# | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 54 | AAV5 | 2e13 | 41.5 (19-75) | 25.9 | 26.5 | 81/19 | Month 7 |

| NCT01687608 (1/2) | BAX335 | United States | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 8 | AAV8 | 2e11, 1e12, 3e12 | 30.5 (20-69) | 12.5 | 86 | NR | NR |

| NCT00979238 (1) | scAAV2/8-LP1-hFIXco | United States, United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 10 | AAV8 | 2e11, 6e11, 2e12 | 36.3 (22-64) | NR | 128 | 100/0 | NR |

| 101HEMB01/NCT02618915 (1/2) | DTX101 | United States, Bulgaria, United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 6 (3, 3) | AAVrh10 | 1.6e12, 5e12 | (50-84, 18-49) | NR | 12 | NR | Day 0 |

| NCT04135300 (1) | BBM-H901 | China | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 10 | AAV843 | 5e12 | NR | 100 | 13 | NR | NR |

| NCT00515710 (1/2) | AAV2-hFIX16 | United States | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 7 | AAV2 | 8e10, 4e11, 2e12 | 34 (20-63) | NR | 180 | 100/0 | NR |

| Trial name/NCT (phase) . | Gene therapy (prior names) . | Setting . | Design . | N∗ (n for individual dose cohorts) . | AAV vector . | Dose(s) (vg/kg) . | Age (y), mean (range) . | Non-White, % . | Duration (mo) . | Hemophilia severity (severe/moderately severe [%]) . | Time at which ABR measurement started . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | |||||||||||

| Alta/NCT03061201 (1/2) | Giroctocogene fitelparvovec (PF-07055480/SB-525) | United States | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 11 | AAV6 | 9e11, 2e12, 1e13, 3e13 | 30 (18-47) | 18.2 | 62 | 100/0 | Week 3 |

| GENEr8-1/NCT02576795 (1/2) | Valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN-270) | United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 13 (7, 6) | AAV5 | 6e13 4e13 | 30.4 (23-42) 31.3 (22-45) | 14.3 16.7 | 72 | 100/0 | Week 4 |

| GENEr8-1/NCT03370913 (3) | Valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN-270) | 13 countries† | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 134 | AAV5 | 6e13 | 31.7 (18-70) | 28.4 | 36 | 100/0 | Week 5 |

| NCT03003533/NCT03432520 (1/2) | Dirloctogene samoparvovec (SPK-8011) | 5 countries‡ | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 24 | AAV3 | 5e11 1e12 1.5e12 2e12 | 32.8 (18-52) | NR | 60 | 94.4/5.6 | Week 4 |

| NCT03734588 (1/2) | SPK-8016 | United States | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 4 | AAV-Spark | 5e11 | (18-63) | NR | 15 | 100/0 | NR |

| NCT03370172 (1/2) | TAK-754 | 8 countries§ | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 4 | AAV8 | 2e12 6e12 | (18-75) | NR | 10 | 100/0 | NR |

| NCT03588299 (1/2) | BAY 2599023 (AAVhu37.hFVIIIco) | 6 countries|| | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 9 | AAVhu37 | 5e12, 1e13, 2e13, 4e13 | NR | NR | 23 | 100/0 | NR |

| NCT03001830GO-8 (1/2) | GO-8 (AAV8-HLP-hFVIII-V3) | United States, United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 12 (1, 3, 3, 5) | AAV8 | 6e11, 2e12, 4e12, 6e12 | NR | NR | 60 | 100/0 | NR |

| HB | |||||||||||

| BENEGENE-2/NCT02484092 (1/2) | Fidanacogene elaparvovec (SPK-9001) | United States, Australia | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 15 | AAV-Spark100 | 5e11 | 35.6 (18-53) | 14.3 | 12 | 60/40 | Day 0 |

| BENEGENE-2/NCT03861273 (3) | Fidanacogene elaparvovec (SPK-9001) | 14 countries¶ | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 45 | AAV-Spark100 | 5e11 | 29 (18-62) | NR | 15 | NR | Week 12 |

| B-LIEVE/NCT05164471 (1/2) | Verbrinacogene setparvovec (FLT180a) | United States, United Kingdom | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 6 | AAVS3 | 7.7e11 | NR | NR | 12 | NR | NR |

| B-AMAZE/NCT03369444 (1/2) | Verbrinacogene setparvovec (FLT180a) | United States, Ireland, Italy, United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 10 (2, 2, 4, 2) | AAVS3 | 3.84e11, 6.4e11, 8.32e11, 1.28e12 | 37.2 (25-67) | 10 | 27.2 | 90/10 | Day 15 |

| NCT02396342 (1/2) | AMT-060 | Denmark, Germany, The Netherlands | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 10 (5, 5) | AAV5 | 5e12 2e13 | 69 (35-72) 35 (33-46) | 0 20 | 60 | 80/20 100/0 | NR |

| HOPE-B/NCT03569891 (2b) | Etranacogene dezaparvovec (AMT-061) | United States | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 3 | AAV5 | 2e13 | 46.7 (43-50) | 66.7 | 36 | 66.7/33.3 | Day 0 |

| HOPE-B/NCT03569891 (3) | Etranacogene dezaparvovec (AMT-061) | 8 countries# | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 54 | AAV5 | 2e13 | 41.5 (19-75) | 25.9 | 26.5 | 81/19 | Month 7 |

| NCT01687608 (1/2) | BAX335 | United States | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 8 | AAV8 | 2e11, 1e12, 3e12 | 30.5 (20-69) | 12.5 | 86 | NR | NR |

| NCT00979238 (1) | scAAV2/8-LP1-hFIXco | United States, United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 10 | AAV8 | 2e11, 6e11, 2e12 | 36.3 (22-64) | NR | 128 | 100/0 | NR |

| 101HEMB01/NCT02618915 (1/2) | DTX101 | United States, Bulgaria, United Kingdom | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 6 (3, 3) | AAVrh10 | 1.6e12, 5e12 | (50-84, 18-49) | NR | 12 | NR | Day 0 |

| NCT04135300 (1) | BBM-H901 | China | Open-label, single-arm, cohort study | 10 | AAV843 | 5e12 | NR | 100 | 13 | NR | NR |

| NCT00515710 (1/2) | AAV2-hFIX16 | United States | Open-label, dose-escalation, cohort study | 7 | AAV2 | 8e10, 4e11, 2e12 | 34 (20-63) | NR | 180 | 100/0 | NR |

NCT, National Clinical Trial; NR, not reported; vg, vector genomes.

For the dose-escalation studies, n for each dose cohort is specified in parentheses for the studies which have specified that data.

United States, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, France, Germany, Israel. Italy, Korea, South Africa, Spain, Taiwan, and United Kingdom.

United States, Australia, Canada, Israel, and Thailand.

United States, United Kingdom, Austria, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, and Spain.

United States, Bulgaria, France, Germany, The Netherlands, and United Kingdom.

United States, Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Japan, Korea, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Taiwan, Turkey, and United Kingdom.

United States, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, The Netherlands, Sweden, and United Kingdom.

Efficacy of AAV-based gene therapy for HA

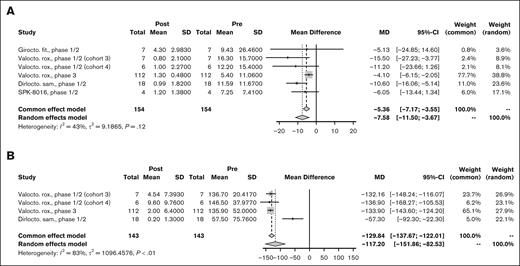

Of 8 studies,38,55,63,112,113 5 reported ABR data for pooled analysis. A random-effects model of 154 PwHA showed a PMD of −7.58 bleeding events per year (95% CI, −11.50 to −3.67; I2 = 43%; P = .12) in favor of the post–gene therapy period (Figure 2A). Three studies38,63,112 representing 143 PwHA reported AIR data with a PMD of −117.20 infusion per year (95% CI, −151.86 to −82.53; I2 = 83%; P < .01; Figure 2B) with significant between-study heterogeneity. There were insufficient data to complete a meta-analysis on annual factor concentrate use. Both studies reporting annual factor concentrate use showed a decrease after gene therapy, with the GENEr8-1 phase 3 trial for valoctocogene roxaparvovec showing a decrease from 3961 to 125 IU/kg per year63 and the phase 1/2 trial for GO-8 showing a decrease from 4097 to 1186 IU/kg per year.23 Measurement of factor levels was done with both OSA and CSA in 5 trials and was not specified in 2 trials. Mean factor levels measured by OSA at 12 months after gene therapy ranged from 10.4 IU/dL in the phase 1/2 trial for SPK-8016113 to 70.31 IU/dL in the 2 highest-dose cohorts (cohorts 3 and 4) in the phase 1/2 trial for valoctocogene roxaparvovec.112 Because of limited data, a meta-analysis of factor levels was not performed.

Efficacy outcomes for HA. Forest plot of individual and PMD with 95% CI in (A) ABR and (B) AIR for AAV-based gene therapies for HA.

Efficacy outcomes for HA. Forest plot of individual and PMD with 95% CI in (A) ABR and (B) AIR for AAV-based gene therapies for HA.

Safety of AAV-based gene therapy for HA

Six studies reported AEs and 7 studies reported serious AEs of AAV-based gene therapy for HA. Overall, 99% of PwHA experienced an AE (95% CI, 49-100; Figure 3A) and 19% experienced a serious AE (95% CI, 10-31; Figure 3B). There was no evidence of significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 0% and P > .05 for both). ALT elevation was reported in 7 studies, which occurred in 71% (95% CI, 50-85) of PwHA, with evidence of significant heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 67%, P < .01; Figure 3C). On sensitivity analysis, there was evidence suggesting the existence of between-study heterogeneity after the removal of 2 studies99,113 with outlier results detected by z score (supplemental Table 2). Two studies reported anaphylaxis, which occurred in 2.2% of PwHA in the GENEr8-1 study of valoctocogene roxaparvovec63 and 0% in the phase 1/2 study of dirloctocogene samoparvovec.38 All studies reported no inhibitor formation or thrombosis.

Safety outcomes for HA. Forest plot of individual and pooled proportion with 95% CI of patients who experienced (A) AE, (B) serious AE, and (C) ALT elevation for AAV-based gene therapies for HA.

Safety outcomes for HA. Forest plot of individual and pooled proportion with 95% CI of patients who experienced (A) AE, (B) serious AE, and (C) ALT elevation for AAV-based gene therapies for HA.

Efficacy of AAV-based gene therapy for HB

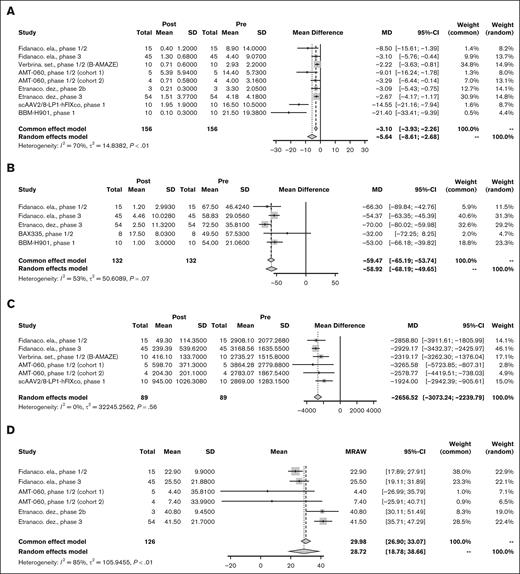

Eight studies8,22,26,28,33,69,73 representing 156 PwHB were included in the pooled analysis for ABR. The PMD for ABR throughout follow-up was −5.64 (95% CI, −8.61 to −2.68) bleeding events per year with significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 70%; P < .01; Figure 4A). On sensitivity analysis, removal of the 2 outlying studies28,73 on funnel plot suggested that there was evidence showing nonsignificant between-study heterogeneity for the remaining studies (supplemental Table 3). Five studies8,26,28,33,52 reporting AIR had a PMD of −58.92 (95% CI, −68.19 to −49.65) infusions per year without significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 53%; P = .07; Figure 4B). Data on annualized use of factor concentrate was available in 5 studies,22,26,33,69,73 showing a PMD of −2656.52 (95% CI, −3073.24 to −2239.79) IU/kg per year without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%; P = .56; Figure 4C). Two studies reporting annualized factor use in IU per year without participant weight showed a numerical decrease in annualized factor use. The HOPE-B phase 3 trial of etranacogene dezaparvovec showed a decrease from 257 338 to 8486 IU per year,8 and the phase 1/2 trial of BAX335 showed a decrease from 221 250 to 99 941 IU per year.52 Factor level measurement was reported with OSA alone in 7 studies, both OSA and CSA in 2 studies, and not reported in 3 studies. Factor level by OSA at 12 months after gene therapy administration was pooled for meta-analysis across 5 studies8,26,33,69 representing 126 PwHB with a mean FIX level of 28.72 IU/dL (95% CI, 18.78-38.66) with statically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 85%; P < .01; Figure 4D). On sensitivity analysis, after removing 2 outlying studies detected by z score, the phase 2b and 3 trials for etranacogene dezaparvovec,8,69 the I2 value of 0% suggested the nonsignificant between-study heterogeneity for the remaining studies (supplemental Table 3).

Efficacy outcomes for HB. Forest plot of individual and PMD with 95% CI in (A) ABR, (B) AIR, (C) annualized factor use (IU/kg), and (D) FIX level at 12 months for AAV-based gene therapies for HB. MD, mean difference; MRAW, raw mean.

Efficacy outcomes for HB. Forest plot of individual and PMD with 95% CI in (A) ABR, (B) AIR, (C) annualized factor use (IU/kg), and (D) FIX level at 12 months for AAV-based gene therapies for HB. MD, mean difference; MRAW, raw mean.

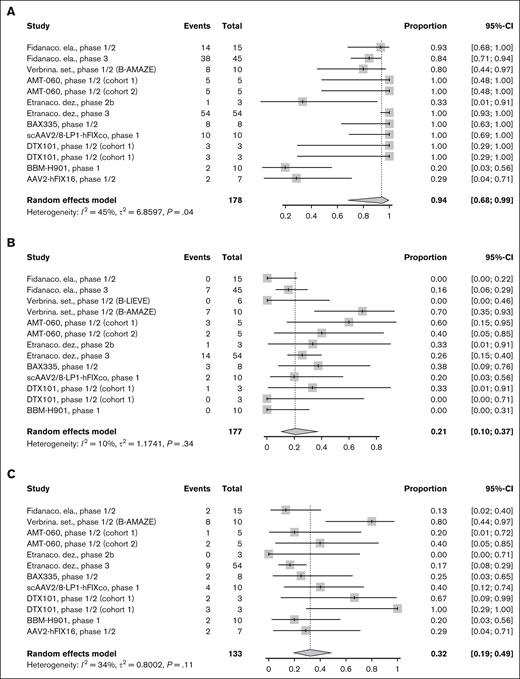

Safety of AAV-based gene therapy for HB

Eleven trials reported AEs and serious AEs with 94% of PwHB experiencing an AE (95% CI, 68-99; Figure 5A) with statistically significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 45%; P = .04) and 21% experiencing a serious AE (95% CI, 10-37; Figure 5B) with nonsignificant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 10%; P = .34). ALT elevation was reported in 10 studies and occurred in 32% of PwHB (95% CI, 19-49) with nonsignificant heterogeneity (I2 = 34%; P = .11; Figure 5C). Three studies reported no incidence of anaphylaxis. No study reported formation of an inhibitor or thrombosis.

Safety outcomes for HB. Forest plot of individual and pooled proportion with 95% CI of patients who experienced (A) AE, (B) serious AE, and (C) ALT elevation for AAV-based gene therapies for HB.

Safety outcomes for HB. Forest plot of individual and pooled proportion with 95% CI of patients who experienced (A) AE, (B) serious AE, and (C) ALT elevation for AAV-based gene therapies for HB.

Durability of gene expression for HA and HB beyond 12 months

For trials reporting factor levels at 24 months after administration of gene therapy, we compared the highest previously reported factor level with the factor level at 24 months, weighted by size of study population. HA gene therapies fell to 55.8% of their peak FVIII level at 24 months. HB gene therapies fell to 95.7% of their peak FIX level at 24 months.

Risk-of-bias assessment

All trials followed a before-after or pre-post design and were assessed with the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies with no control group. We assessed the plurality (10, 50.0%) of trials to have good quality; 6 (30.0%) trials were assessed to have fair quality; and 4 (20.0%) trials to have poor quality, primarily because of missing methodological information (Table 2).

Risk-of-bias assessment

| Trial name/NCT (phase) . | Gene therapy (prior names) . | 1. Study question . | 2. Eligibility criteria and study population . | 3. Study participants representative of clinical populations of interest . | 4. All eligible participants enrolled . | 5. Sample size . | 6. Intervention clearly described . | 7. Outcome measures clearly described, valid, and reliable . | 8. Blinding of outcome assessors . | 9. Follow-up rate . | 10. Statistical analysis . | 11. Multiple outcome measures . | 12. Group-level interventions and individual-level outcome efforts . | Quality rating . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | ||||||||||||||

| Alta/NCT03061201 (1/2) | Giroctocogene fitelparvovec (PF-07055480/SB-525) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | N | Y | NR | Y | NA | Fair |

| GENEr8-1/NCT02576795 (1/2) | Valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN-270) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | N | NR | NR | Y | NR | Fair |

| GENEr8-1/NCT03370913 (3) | Valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN-270) | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | NR | NR | Good |

| NCT03003533/NCT03432520 (1/2) | Dirloctocogene samoparvovec (SPK-8011) | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| NCT03734588 (1/2) | SPK-8016 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | NR | NA | Fair |

| NCT03370172 (1/2) | TAK-754 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | N | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| NCT03588299 (1/2) | BAY 2599023 (AAVhu37.hFVIIIco) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | NA | Poor |

| NCT03001830GO-8 (1/2) | GO-8 (AAV8-HLP-hFVIII-V3) | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| HB | ||||||||||||||

| BENEGENE-2/NCT02484092 (1/2) | Fidanacogene elaparvovec (SPK-9001) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| BENEGENE-2/NCT03861273 (3) | Fidanacogene elaparvovec (SPK-9001) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| B-LIEVE/NCT05164471 (1/2) | Verbrinacogene setparvovec (FLT180a) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | NR | NR | NR | NA | Poor |

| B-AMAZE/NCT03369444 (1/2) | Verbrinacogene setparvovec (FLT180a) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | NR | NR | NR | Good |

| NCT02396342 (1/2) | AMT-060 | Y | Y | Y | Y | CD | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| HOPE-B/NCT03569891 (2b) | Etranacogene dezaparvovec (AMT-061) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | Y | N | NR | NA | Fair |

| HOPE-B/NCT03569891 (3) | Etranacogene dezaparvovec (AMT-061) | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good |

| NCT01687608 (1/2) | BAX335 | Y | Y | Y | NR | CD | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| NCT00979238 (1) | scAAV2/8-LP1-hFIXco | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | NR | NR | Fair |

| 101HEMB01/NCT02618915 (1/2) | DTX101 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| NCT04135300 (1) | BBM-H901 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | NR | N | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| NCT00515710 (1/2) | AAV2-hFIX16 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NA | Fair |

| Trial name/NCT (phase) . | Gene therapy (prior names) . | 1. Study question . | 2. Eligibility criteria and study population . | 3. Study participants representative of clinical populations of interest . | 4. All eligible participants enrolled . | 5. Sample size . | 6. Intervention clearly described . | 7. Outcome measures clearly described, valid, and reliable . | 8. Blinding of outcome assessors . | 9. Follow-up rate . | 10. Statistical analysis . | 11. Multiple outcome measures . | 12. Group-level interventions and individual-level outcome efforts . | Quality rating . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | ||||||||||||||

| Alta/NCT03061201 (1/2) | Giroctocogene fitelparvovec (PF-07055480/SB-525) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | N | Y | NR | Y | NA | Fair |

| GENEr8-1/NCT02576795 (1/2) | Valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN-270) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | N | NR | NR | Y | NR | Fair |

| GENEr8-1/NCT03370913 (3) | Valoctocogene roxaparvovec (BMN-270) | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | NR | NR | Good |

| NCT03003533/NCT03432520 (1/2) | Dirloctocogene samoparvovec (SPK-8011) | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| NCT03734588 (1/2) | SPK-8016 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | NR | NA | Fair |

| NCT03370172 (1/2) | TAK-754 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | N | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| NCT03588299 (1/2) | BAY 2599023 (AAVhu37.hFVIIIco) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | NA | Poor |

| NCT03001830GO-8 (1/2) | GO-8 (AAV8-HLP-hFVIII-V3) | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| HB | ||||||||||||||

| BENEGENE-2/NCT02484092 (1/2) | Fidanacogene elaparvovec (SPK-9001) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| BENEGENE-2/NCT03861273 (3) | Fidanacogene elaparvovec (SPK-9001) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| B-LIEVE/NCT05164471 (1/2) | Verbrinacogene setparvovec (FLT180a) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | NR | NR | NR | NA | Poor |

| B-AMAZE/NCT03369444 (1/2) | Verbrinacogene setparvovec (FLT180a) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | NR | NR | NR | Good |

| NCT02396342 (1/2) | AMT-060 | Y | Y | Y | Y | CD | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| HOPE-B/NCT03569891 (2b) | Etranacogene dezaparvovec (AMT-061) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | Y | N | NR | NA | Fair |

| HOPE-B/NCT03569891 (3) | Etranacogene dezaparvovec (AMT-061) | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good |

| NCT01687608 (1/2) | BAX335 | Y | Y | Y | NR | CD | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| NCT00979238 (1) | scAAV2/8-LP1-hFIXco | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | NR | NR | Fair |

| 101HEMB01/NCT02618915 (1/2) | DTX101 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | NA | Good |

| NCT04135300 (1) | BBM-H901 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | NR | N | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| NCT00515710 (1/2) | AAV2-hFIX16 | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | Y | NA | Fair |

CD, cannot determine; N, no; NA, not applicable; NCT, National Clinical Trial; NR, not reported; Y, yes.

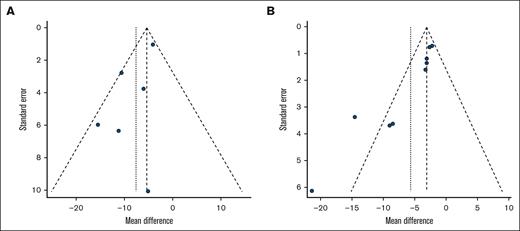

Publication bias

On evaluation for publication bias for the primary outcome of ABR, funnel plots and Egger tests were used. The results indicated that nonsignificant heterogeneity was present for HA gene therapies (P = .0876; Figure 6A). For HB, the Egger test was significant (P = .0006), with the funnel plot showing asymmetry, especially for 2 studies28,73 with a larger absolute PMD and relatively larger standard error, which may overestimate the magnitude of the point estimate for ABR in HB gene therapies (Figure 6B; supplemental Table 3).

Publication bias. Funnel plot for trials of AAV-based gene therapies for (A) HA and (B) HB.

Publication bias. Funnel plot for trials of AAV-based gene therapies for (A) HA and (B) HB.

Discussion

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy and safety of AAV-based gene therapies for HA and HB. We found that PwHA and PwHB had significantly lower annualized bleeding events and factor infusion requirements after gene therapy compared with factor prophylaxis before gene therapy. At 24 months, we observed that factor levels declined to 55.8% of their peak level among PwHA, whereas they remained durable among PwHB. Treatment was well tolerated. There was no inhibitor formation or thrombotic events reported among eligible studies.

AAV-based gene therapy has emerged as a promising treatment for PwHA and PwHB, offering advantages over prophylaxis with factor concentrate or emicizumab. As our results show, a single infusion of vector reduces bleeding and mitigates or eliminates the burden of frequent infusions compared with prophylaxis with factor concentrate. However, more work is needed to optimize gene therapy for hemophilia before it can be considered a treatment of choice for most patients.

First, most studies we identified excluded patients with neutralizing anticapsid antibodies or a history of inhibitors to FVIII or FIX, greatly limiting who is eligible to receive treatment. Efforts to expand eligibility for these therapies is paramount.

Second, improving the prevention, detection, and management of anticapsid immune responses is a priority. Such responses typically manifest as hepatic transaminase elevation. Prompt treatment, typically with corticosteroids, is necessary to minimize loss of factor expression.75,124 Our results suggest heterogeneity between gene therapy products with respect to the incidence of ALT elevation. Some of this heterogeneity may be due to protocol-specific factors. Protocols used different cutoffs for both grading ALT elevation (usually either 1.5- or twofold above baseline levels or upper limit of normal) and for initiating immunosuppression in response to ALT elevation. Likewise, some protocols used prophylactic prednisolone and tacrolimus22 in the initial post–gene therapy period to mitigate vector-related hepatotoxicity whereas others advised initiation of immunosuppression only in those who developed ALT elevation. These protocol differences and limited subject-level data preclude pooled analysis on the impacts of ALT elevation and use of immunosuppression on durability of factor expression and highlight the need for further research to optimize use of immunosuppression.

Higher rates of ALT elevation were observed in gene therapies for HA relative to HB, perhaps because of higher vector doses used in HA. In phase 1/2 studies reporting hepatotoxicity by dose cohorts, higher doses appeared to yield more hepatotoxicity.22,69 Higher vector doses were also associated with prolonged time to vector clearance from body fluids, such as semen.33 The impact of vector dose on the incidence and severity of other AEs merits further investigation.

Because the ultimate vision for gene therapy is a 1-time cure, the long-term durability of clotting factor expression is critical. Our results highlight what others have found, AAV-based gene therapy for HB appears to produce stable gene expression for at least 10 years whereas FVIII levels in PwHA tend to decline over time, at least with some products.108 Although gene therapy may reduce health care costs in the long-term, current pricing in the United States between $2 to $3 million may be cost-prohibitive for some patients based on their insurance coverage, geographic location, and health care system. Further study on duration of effect may yield a better understanding of the cost-effectiveness of gene therapy.125 Additionally, long-term data regarding safety and potential toxicities such as risk for insertional mutagenesis need to be further explored through long-term follow-up.126,127

Our results are in general alignment with another recently published systematic review and meta-analysis on AAV-based gene therapy for hemophilia by Han et al,128 which also demonstrated significant reductions in ABR and AIR after vector infusion. However, we believe that our point estimates are more accurate because we combined successive publications of the same trial into 1 set of outcomes. In contrast, Han et al counted multiple publications of the same trial with the same participants as distinct studies with distinct outcomes, an error known as double-counting bias.129

A key strength of our analysis is its completeness. By extracting data from peer-reviewed manuscripts, conference proceedings, and ClinicalTrials.gov, we were able to include data with the longest follow-up and most complete outcomes.

Our study also has limitations. First, all of the included studies followed a nonrandomized, single-group pre/post (before/after) design rather than a randomized controlled trial, although this is a typical and reasonable approach when recruitable participants are limited in rare diseases.130 This trial design limited our ability to directly compare gene therapies with other therapies of interest such as emicizumab and extended half-life factor prophylaxis. A second limitation is the intrinsic heterogeneity between different gene therapy products and certain aspects of their study designs. Nevertheless, the similar use of AAV vectors, study populations, pre/post study designs, and outcomes support the pooling of data in this context. The direction of treatment effect was uniformly in favor of gene therapy for the primary outcome (ABR), further supporting our use of meta-analysis. Finally, there were limitations to data availability. Some trials were only published as abstracts, or their latest results were published as abstracts with incomplete reporting of methods and outcomes. When possible, patient-level data were used, but they were not uniformly available.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that AAV-based gene therapies for both HA and HB significantly reduce ABR, AIR, and factor use with achievement of hemostatic factor levels and an acceptable safety profile. FIX levels generally remained stable over 2 years, whereas FVIII levels showed a tendency to decline over time. The place of gene therapy in the evolving landscape of hemophilia treatment remains to be determined. Although uptake has been slow to date,131 AAV-based gene therapy represents an attractive option for patients who place a high value on freedom from regular treatment. Efforts to expand eligibility, minimize anticapsid immune responses, improve durability of factor expression, reduce costs, and expand access will only augment the potential of this game-changing therapy.

Authorship

Contribution: S.R.D. and K.J. performed the literature search, data screening, data collection, quality appraisal of studies, and manuscript drafting; J.T. and Y.C. assisted with the statistical analysis, and reviewed and edited the manuscript; A.P. provided guidance during all phases of this project in addition to performing a thorough review of the manuscript; A.C. designed the study, provided guidance during all phases of the project, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.C. has served as a consultant for MingSight, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Synergy, and has received authorship royalties from UpToDate. A.P. has served on the advisory board for BioMarin and receives authorship royalties from UpToDate. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Saarang R. Deshpande, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104; email: saarang.deshpande@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Saarang R. Deshpande (saarang.deshpande@pennmedicine.upenn.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.