Key Points

No difference in the cumulative incidence of bleeding in ET patients with vs without ExT.

There is no clear indication for cytoreduction to decrease bleeding risk based on a platelet threshold of 1 million alone.

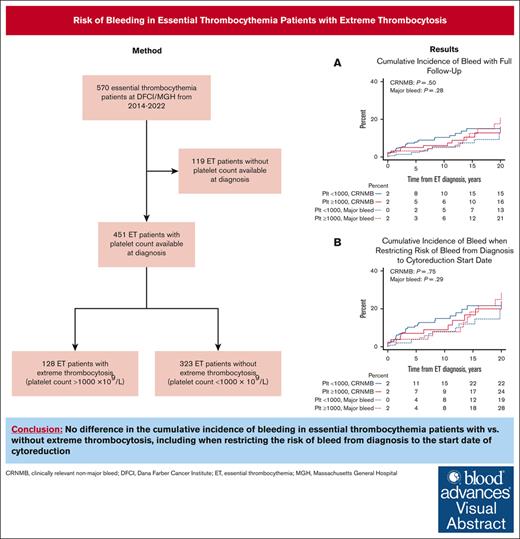

Visual Abstract

Approximately 25% of patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) present with extreme thrombocytosis (ExT), defined as having a platelet count ≥1000 × 109/L. ExT patients may have an increased bleeding risk associated with acquired von Willebrand syndrome. We retrospectively analyzed the risk of bleeding and thrombosis in ExT vs non-ExT patients with ET at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital from 2014 to 2022 to inform treatment decisions. We abstracted the first major bleed, clinically relevant nonmajor bleed (CRNMB), and thrombotic events from medical records. We identified 128 ExT patients (28%) and 323 non-ExT patients (72%). Cumulative incidence of bleeding was not different in ExT vs non-ExT patients (21% vs 13% [P = .28] for major bleed; 16% vs 15% [P = .50] for CRNMB). Very low and low thrombotic risk ExT patients were more likely to be cytoreduced than very low- and low-risk non-ExT patients (69% vs 50% [P = .060] for very low risk; 83% vs 53% [P = .0059] for low risk). However, we found no differences in bleeding between ExT and non-ExT patients when restricting the risk of bleed from diagnosis to cytoreduction start date (28% vs 19% [P = .29] for major bleed; 24% vs 22% [P = .75] for CRNMB). Cumulative incidence of thrombosis was also not different between ExT and non-ExT patients (28% vs 25%; P = .98). This suggests that cytoreduction may not be necessary to reduce bleeding risk based only on a platelet count of 1 million. We identified novel risk factors for bleeding in patients with ET including diabetes mellitus and the DNMT3A mutation.

Introduction

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) characterized by recurrent mutations in 1 of 3 driver genes: JAK2, CALR, and MPL.1-3 Thrombosis is the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in ET.4,5 Incidence rates of thrombosis range from 9% to 22% in patients with ET at the time of diagnosis, and patients with a JAK2 mutation are at higher risk.6,7 Risk stratification and treatment management in ET are based on thrombosis risk.8,9 Patients considered high risk (patients aged >60 years with a JAK2 mutation or patients with a history of thrombosis) by the revised International Prognostic Score of Thrombosis for ET (R-IPSET) are started on a cytoreductive agent to normalize blood counts, and in general, all JAK2-mutated patients are treated with low-dose aspirin.10-12

Cytoreduction may also be considered when patients develop extreme thrombocytosis (ExT), arbitrarily defined as having a platelet count >1000 × 109/L, although the risks/benefits of cytoreduction are unclear in this setting.13,14 ExT is seen in 22% of patients with ET overall and in 44% of patients with ET aged <40 years old.15 Patients with CALR mutations, who are considered lower risk for thrombosis, also frequently present with ExT.15-18 Despite the elevated platelet counts, ExT has not been shown to confer increased thrombosis risk based on multiple retrospective studies.17,19,20 However, ExT patients are often started on cytoreduction, possibly due to the risk of bleeding associated with their high platelet count. Data have demonstrated that the risk of bleeding in ET follows a U shaped curve, with increased major bleeding at platelet counts below (<150 × 109/L) and above the normal range (>450 × 109/L).21 One of the mechanisms thought to result in increased bleeding is acquired von Willebrand syndrome (AVWS). Elevated platelet counts can result in increased proteolysis of high molecular weight von Willebrand factor (VWF) multimers, leading to a qualitative defect in VWF.22 The prevalence of AVWS in patients with ET has been reported to range from 20% to 55% depending on definition, and there are limited data on AVWS in ExT patients.22,23

The risk of bleeding is unclear in ExT patients specifically. Consequently, there are no treatment guidelines on the management of bleeding risk in ExT patients, including (1) when to start cytoreduction, (2) when to stop aspirin, and (3) how to incorporate AVWS testing. Risk factors associated with bleeding in ExT patients are also unknown, making it difficult to know whether there are specific subpopulations of ExT patients who may benefit from cytoreductive therapy.

Thus, we first aimed to characterize the risk of bleeding in patients with ET with ExT. We further sought to analyze risk factors that contribute to bleeding and investigate thrombosis, progression, and survival outcomes in patients with ET with ExT.

Methods

Study design and sample

This was a bicentric, retrospective cohort study of patients with ET included in the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) Hematologic Malignancies Data Repository (HMDR) and the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) MPN database. HMDR is a curated clinical, pathologic, and genetic database of patients with hematologic malignancies seen at DFCI from 2014 to 2022. The MGH MPN database includes patients found to have an MPN by the World Health Organization 2016 criteria through International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision codes from 2014 to 2022. Medical record review was performed to confirm that patients met the World Health Organization 2016 criteria for ET.24 Both databases include next-generation sequencing panels in up to 95 genes that are recurrently mutated in myeloid and lymphoid malignancies.25,26

We used REDCap, a secure web-based electronic data capture tool hosted by Mass General Brigham, to abstract data from medical records. The HMDR and MGH MPN study protocols were approved by the DFCI and MGH Institutional Review Boards, respectively, and included waiver of informed consent for retrospective chart review.

Definitions of outcomes and covariates

Clinical variables and outcomes, including patient demographics, cardiovascular comorbidities, platelet and white blood cell (WBC) counts at diagnosis, mutation status, history of thrombosis, first von Willebrand laboratory results, ET treatment and cytoreduction start date, date of ET diagnosis, date of last visit, date of death, and acute myeloid leukemia and myelofibrosis transformation dates, were abstracted by medical record review or International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision codes. We defined ExT as having a platelet count at ET diagnosis of >1000 × 109/L. We also examined 1500 × 109/L as the platelet cutoff for ExT because the definitions of ExT vary. First bleeding and thrombosis events in a patient’s ET disease course were collected. Consistent with other MPN studies, we captured events up to 2 years before ET diagnosis.27-30 Bleeding was categorized as either major bleeding or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (CRNMB) using the International Society on Thrombosis & Haemostasis definitions.31 Major bleeding was defined as bleeding leading to death, organ bleeding resulting in symptoms, and/or bleeding requiring a transfusion of 2 units or leading to a reduction in hemoglobin of 2 g/dL.31 CRNMB was defined as bleeding that does not satisfy the major bleeding threshold but leads to a clinical encounter including a hospital admission, a treatment to stop the bleed (medical or surgical), or an alteration of antithrombotic medicine.31 We identified the site of bleed including gastrointestinal, intracranial, retroperitoneal, hematuria, heavy period, or other. If there was doubt on bleeding categorization, we reviewed the bleed with a third-party objective hematologist.

Thrombosis was categorized as either arterial or venous. Arterial thrombosis was defined as myocardial infarction, angina, cerebrovascular accidents, transient ischemic attack, peripheral arterial thrombosis, aortic thrombosis, mesenteric artery thrombosis, or central retinal thrombosis. Venous thrombosis was defined as deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, portal/splenic/mesenteric/hepatic vein thrombosis, or cerebral sinus thrombosis.

Statistical analysis

We first excluded patients for whom we could not identify a platelet count at diagnosis. We showed baseline data with summary statistics for ExT and non-ExT patients, and we presented continuous variables as mean with standard deviation and categorical variables as frequency with proportion.

We then reported crude major bleeding, CRNMB, and thrombosis outcomes in ExT and non-ExT patients. We reported the site of bleed and type of thrombosis. We subsequently determined the 2-year and 20-year (full follow-up) cumulative incidence rates of bleeding and thrombosis in ExT and non-ExT patients after ET diagnosis. Time to bleeding/thrombosis was defined as the time from ET diagnosis to a bleeding or thrombosis event. Bleeding/thrombosis events from up to 2 years before ET diagnosis were characterized as occurring at diagnosis. A competing risk model was fitted, with bleeding or thrombosis as the event of interest and death as a competing event. In these models, we used a competing incidence function to describe the risk of an event. A Gray test was used to compare cumulative incidence between patients with and without ExT. We also assessed ET treatment by R-IPSET score. Risk factors for combined major bleeding and CRNMB were evaluated using univariate and multivariate Fine-Gray models.32 Multivariable models were adjusted for variables significant in univariate analysis, in addition to variables that could potentially affect the pathophysiology of bleeding. We performed secondary analyses including using 1500 × 109/L as the platelet cutoff for ExT and restricting follow-up to the start date of cytoreduction for patients treated with cytoreduction.

Lastly, we analyzed overall survival, myelofibrosis-free survival, leukemia-free survival, thrombosis-free survival, and bleeding-free survival in ExT and non-ExT patients using Kaplan-Meier curves. We conducted all analyses using R (version 4.3.2.), and a 2-sided P value of <.05 was reported as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of ExT and non-ExT patients at ET diagnosis

A total of 451 patients with ET with baseline platelet counts available at diagnosis were included in our analysis, of 570 total patients in the study sample. There were 128 ExT patients (28%) and 323 non-ExT patients (72%). The median follow-up was 12 (95% confidence interval [CI], 10-15) and 6 years (95% CI, 5-8), and the median platelet count at ET diagnosis was 1196 (range, 1000-4055) and 661 (range, 400-997), respectively. Most patients were seen at DFCI vs MGH (91% vs 9%), and there was no difference in the percent of ExT patients at each institution. ExT patients were more likely to be younger (50 vs 57; P < .001) and male (51% vs 39%; P = .026) than non-ExT patients. In all patients with ET, 88% of patients were White, 7% had diabetes mellitus, and 3% and 27% were current and former smokers, respectively; these variables were similar between the groups. ExT patients had lower rates of hypertension (9% vs 17%; P = .019) and hyperlipidemia (10% vs 17%; P = .080). ExT patients were more likely to have the CALR mutation (48% vs 22%) and less likely to have the JAK2 mutation (31% vs 59%; P < .001). Of all patients with ET in our sample, 8.6% had a nonphenotypic driver mutation. The most common nondriver mutations in all patients with ET were TET2 (15/451 [3%]), DNMT3A (16/451 [4%]), and ASXL1 (7/451 [3%]). No nondriver mutations were associated with ExT. Patients with ExT were also more likely to be at very low R-IPSET risk (42% vs 20% very low risk, 19% vs 31% low risk, 13% vs 12% intermediate risk, and 12% vs 28% high risk; P < .001); but the history of thrombosis any time before ET diagnosis was similar between the groups (10% vs 11%; P = .87). VWF antigen and activity levels were available in 35% of ExT patients and 18% of non-ExT patients. ExT patients had lower VWF antigen (89 vs 114; P = .028) and activity (61% vs 89%; P < .001) levels. The types of ET treatment did not differ between ExT vs non-ExT (or vice versa) groups regarding aspirin alone (20% vs 28%; P = .092), aspirin with cytoreduction (62% vs 63%; P > .99), and any cytoreduction (77% vs 71%; P = .29; Table 1). However, when examining ET treatment by R-IPSET score, very low- and low-risk ExT patients were more likely to be treated with cytoreduction (69% vs 50% [P = .060] for very low risk; 83% vs 53% [P = .0059] for low risk) and less likely to be treated with aspirin alone (26% vs 47% [P = .023] for very low risk; 17% vs 45% [P = .011] for low risk) than very low- and low-risk non-ExT patients, respectively (Table 2). There was no difference in the treatment of intermediate-risk ExT patients, whereas high-risk ExT patients were less likely to be treated with cytoreduction than high-risk non-ExT patients (81% vs 97%; P = .044).

Baseline demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, diagnosis characteristics, first von Willebrand laboratory results, and ET treatment in ExT and non-ExT patients

| . | Total . | Platelet count ≥1000 × 109/L . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No . | Yes . | |||

| N = 451 (%) . | n = 323 (72) . | n = 128 (28) . | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Institution | ||||

| DFCI | 412 (91) | 294 (91) | 118 (92) | .85∗ |

| MGH | 39 (9) | 29 (9) | 10 (8) | |

| Follow-up, median (95% CI) | 8 (6-9) | 6 (5-8) | 12 (10-15) | <.001† |

| Age at ET diagnosis, median (range) | 56 (10-96) | 57 (10-96) | 50 (12-84) | <.001‡ |

| Female sex | 260 (58) | 197 (61) | 63 (49) | .026∗ |

| Race | ||||

| White | 399 (88) | 285 (88) | 114 (89) | .59∗ |

| Black | 17 (4) | 11 (3) | 6 (5) | |

| Asian | 16 (4) | 11 (3) | 5 (4) | |

| Other/unknown | 19 (4) | 16 (5) | 3 (2) | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors at diagnosis | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (7) | 24 (7) | 9 (7) | >.99∗ |

| Hypertension | 67 (15) | 56 (17) | 11 (9) | .019∗ |

| Hyperlipidemia | 67 (15) | 54 (17) | 13 (10) | .080∗ |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 205 (45) | 144 (45) | 61 (48) | .78∗ |

| Former | 120 (27) | 84 (26) | 36 (28) | |

| Current | 15 (3) | 12 (4) | 3 (2) | |

| Diagnosis characteristics | ||||

| Driver mutation | ||||

| CALR | 132 (29) | 71 (22) | 61 (48) | <.001∗ |

| JAK2 | 232 (51) | 192 (59) | 40 (31) | |

| MPL | 19 (4) | 13 (4) | 6 (5) | |

| Triple Neg | 50 (11) | 34 (11) | 16 (12) | |

| Platelet count at diagnosis, median (range), ×109/L | 775 (400-4055) | 661 (400-997) | 1196 (1000-4055) | <.001‡ |

| WBC count at diagnosis, median (range), ×109/L | 8.75 (3.60-61.52) | 8.41 (3.60-30.80) | 9.53 (3.70-61.52) | .031‡ |

| History of thrombosis before ET diagnosis | 49 (11) | 36 (11) | 13 (10) | .87∗ |

| R-IPSET thrombosis risk | ||||

| Very low risk | 118 (26) | 64 (20) | 54 (42) | <.001∗ |

| Low risk | 123 (27) | 99 (31) | 24 (19) | |

| Intermediate risk | 56 (12) | 39 (12) | 17 (13) | |

| High risk | 105 (23) | 89 (28) | 16 (12) | |

| First von Willebrand laboratory results in disease course | ||||

| First VWF antigen level, median (range) | 102 (36-297) | 114 (36-297) | 89 (44-187) | .028‡ |

| First VWF activity level, median (range) | 75 (16-90 648) | 89 (19-90 648) | 61 (16-168) | <.001‡ |

| First VWF activity level <50% | 19 (4) | 6 (2) | 13 (10) | .021∗ |

| ET treatment during disease course | ||||

| No treatment | 7 (2) | 3 (1) | 4 (3) | .10∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 114 (25) | 89 (28) | 25 (20) | .092∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 282 (63) | 202 (63) | 80 (62) | >.99∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 328 (73) | 230 (71) | 98 (77) | .29∗ |

| Cytoreduction start after diagnosis, median (range), y | 0.7 (0.0-61.8) | 1.0 (0.0-35.6) | 0.1 (0.0-61.8) | .0047‡ |

| Cytoreduction within 2 y after diagnosis | 285 (63) | 196 (61) | 89 (70) | .084∗ |

| . | Total . | Platelet count ≥1000 × 109/L . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No . | Yes . | |||

| N = 451 (%) . | n = 323 (72) . | n = 128 (28) . | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Institution | ||||

| DFCI | 412 (91) | 294 (91) | 118 (92) | .85∗ |

| MGH | 39 (9) | 29 (9) | 10 (8) | |

| Follow-up, median (95% CI) | 8 (6-9) | 6 (5-8) | 12 (10-15) | <.001† |

| Age at ET diagnosis, median (range) | 56 (10-96) | 57 (10-96) | 50 (12-84) | <.001‡ |

| Female sex | 260 (58) | 197 (61) | 63 (49) | .026∗ |

| Race | ||||

| White | 399 (88) | 285 (88) | 114 (89) | .59∗ |

| Black | 17 (4) | 11 (3) | 6 (5) | |

| Asian | 16 (4) | 11 (3) | 5 (4) | |

| Other/unknown | 19 (4) | 16 (5) | 3 (2) | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors at diagnosis | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (7) | 24 (7) | 9 (7) | >.99∗ |

| Hypertension | 67 (15) | 56 (17) | 11 (9) | .019∗ |

| Hyperlipidemia | 67 (15) | 54 (17) | 13 (10) | .080∗ |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 205 (45) | 144 (45) | 61 (48) | .78∗ |

| Former | 120 (27) | 84 (26) | 36 (28) | |

| Current | 15 (3) | 12 (4) | 3 (2) | |

| Diagnosis characteristics | ||||

| Driver mutation | ||||

| CALR | 132 (29) | 71 (22) | 61 (48) | <.001∗ |

| JAK2 | 232 (51) | 192 (59) | 40 (31) | |

| MPL | 19 (4) | 13 (4) | 6 (5) | |

| Triple Neg | 50 (11) | 34 (11) | 16 (12) | |

| Platelet count at diagnosis, median (range), ×109/L | 775 (400-4055) | 661 (400-997) | 1196 (1000-4055) | <.001‡ |

| WBC count at diagnosis, median (range), ×109/L | 8.75 (3.60-61.52) | 8.41 (3.60-30.80) | 9.53 (3.70-61.52) | .031‡ |

| History of thrombosis before ET diagnosis | 49 (11) | 36 (11) | 13 (10) | .87∗ |

| R-IPSET thrombosis risk | ||||

| Very low risk | 118 (26) | 64 (20) | 54 (42) | <.001∗ |

| Low risk | 123 (27) | 99 (31) | 24 (19) | |

| Intermediate risk | 56 (12) | 39 (12) | 17 (13) | |

| High risk | 105 (23) | 89 (28) | 16 (12) | |

| First von Willebrand laboratory results in disease course | ||||

| First VWF antigen level, median (range) | 102 (36-297) | 114 (36-297) | 89 (44-187) | .028‡ |

| First VWF activity level, median (range) | 75 (16-90 648) | 89 (19-90 648) | 61 (16-168) | <.001‡ |

| First VWF activity level <50% | 19 (4) | 6 (2) | 13 (10) | .021∗ |

| ET treatment during disease course | ||||

| No treatment | 7 (2) | 3 (1) | 4 (3) | .10∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 114 (25) | 89 (28) | 25 (20) | .092∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 282 (63) | 202 (63) | 80 (62) | >.99∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 328 (73) | 230 (71) | 98 (77) | .29∗ |

| Cytoreduction start after diagnosis, median (range), y | 0.7 (0.0-61.8) | 1.0 (0.0-35.6) | 0.1 (0.0-61.8) | .0047‡ |

| Cytoreduction within 2 y after diagnosis | 285 (63) | 196 (61) | 89 (70) | .084∗ |

Neg, negative.

Boldface type for P values indicates statistical significance.

Fisher exact test.

Log-rank test.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

ET treatment by R-IPSET risk score in ExT and non-ExT patients

| . | Total . | Platelet count ≥1000 × 109/L . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No . | Yes . | |||

| n = 402 (%) . | n = 291 (72) . | n = 111 (28) . | ||

| Very low risk, n = 118 | ||||

| No treatment | 5 (4) | 2 (3) | 3 (6) | .66∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 44 (37) | 30 (47) | 14 (26) | .023∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 61 (52) | 29 (45) | 32 (59) | .14∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 69 (58) | 32 (50) | 37 (69) | .060∗ |

| Low risk, n = 123 | ||||

| No treatment | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | - | >.99∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 49 (40) | 45 (45) | 4 (17) | .011∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 60 (49) | 44 (44) | 16 (67) | .068∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 72 (59) | 52 (53) | 20 (83) | .0059∗ |

| Intermediate risk, n = 56 | ||||

| No treatment | 1 (2) | - | 1 (6) | .30∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 8 (14) | 6 (15) | 2 (12) | >.99∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 43 (77) | 32 (82) | 11 (65) | .18∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 47 (84) | 33 (85) | 14 (82) | >.99∗ |

| High risk, n = 105 | ||||

| No treatment | - | - | - | >.99∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 2 (12) | .17∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 86 (82) | 75 (84) | 11 (69) | .16∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 99 (94) | 86 (97) | 13 (81) | .044∗ |

| . | Total . | Platelet count ≥1000 × 109/L . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No . | Yes . | |||

| n = 402 (%) . | n = 291 (72) . | n = 111 (28) . | ||

| Very low risk, n = 118 | ||||

| No treatment | 5 (4) | 2 (3) | 3 (6) | .66∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 44 (37) | 30 (47) | 14 (26) | .023∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 61 (52) | 29 (45) | 32 (59) | .14∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 69 (58) | 32 (50) | 37 (69) | .060∗ |

| Low risk, n = 123 | ||||

| No treatment | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | - | >.99∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 49 (40) | 45 (45) | 4 (17) | .011∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 60 (49) | 44 (44) | 16 (67) | .068∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 72 (59) | 52 (53) | 20 (83) | .0059∗ |

| Intermediate risk, n = 56 | ||||

| No treatment | 1 (2) | - | 1 (6) | .30∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 8 (14) | 6 (15) | 2 (12) | >.99∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 43 (77) | 32 (82) | 11 (65) | .18∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 47 (84) | 33 (85) | 14 (82) | >.99∗ |

| High risk, n = 105 | ||||

| No treatment | - | - | - | >.99∗ |

| Aspirin alone | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 2 (12) | .17∗ |

| Aspirin with cytoreductive agent | 86 (82) | 75 (84) | 11 (69) | .16∗ |

| Any cytoreduction | 99 (94) | 86 (97) | 13 (81) | .044∗ |

Boldface type for P values indicates statistical significance.

Fisher's exact test.

Bleeding and thrombosis cumulative incidence overall and by therapy

There were 13 major bleeds (10%) and 12 CRNMBs (9%) in the 128 ExT patients and 14 major bleeds (4%) and 31 CRNMBs (10%) in the 323 non-ExT patients. Most major bleeds were gastrointestinal bleeds (52% of all major bleeds), whereas most CRNMBs were labeled as other (74% of all CRNMBs), consisting mostly of hematomas, epistaxis, and hemarthrosis (Table 3). Twenty-four of 27 major bleeds and 31 of 43 CRNMBs occurred in patients using cytoreduction at any time during the ET disease course. Among these patients, 76% had major bleeds, and 67% had CRNMBs after the start date of cytoreduction. Additional details on major bleeds and CRNMBs are available in supplemental Table 1.

Crude major bleeding, CRNMB, and thrombosis outcomes in ExT and non-ExT patients

| . | Total . | Platelet count ≥1000 × 109/L . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No . | Yes . | |||

| N = 451 (%) . | n = 323 (72) . | n = 128 (28) . | ||

| Major bleeding | 27 (6) | 14 (4) | 13 (10) | .026∗ |

| Major bleeding site | ||||

| GI | 14 (52) | 7 (50) | 7 (54) | >.99∗ |

| Intracranial | 6 (22) | 3 (21) | 3 (23) | |

| Retroperitoneal | 1 (4) | - | 1 (8) | |

| Hematuria | - | - | - | |

| Heavy period | 1 (4) | 1 (7) | - | |

| Other | 5 (19) | 3 (21) | 2 (15) | |

| CRNMB | 43 (10) | 31 (10) | 12 (9) | >.99∗ |

| CRNMB site | ||||

| GI | 5 (12) | 4 (13) | 1 (8) | .89∗ |

| Intracranial | - | - | - | |

| Retroperitoneal | - | - | - | |

| Hematuria | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | - | |

| Heavy period | 5 (12) | 3 (10) | 2 (17) | |

| Other | 32 (74) | 23 (74) | 9 (75) | |

| Thrombosis | 82 (18) | 55 (17) | 27 (21) | .34∗ |

| Arterial | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 14 (17) | 13 (24) | 1 (4) | .17∗ |

| Stroke | 23 (28) | 15 (27) | 8 (30) | |

| Other | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | 1 (4) | |

| Venous | ||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 15 (18) | 11 (20) | 4 (15) | .22∗ |

| Pulmonary embolism | 9 (11) | 6 (11) | 3 (11) | |

| Splanchnic/abdominal | 12 (15) | 4 (7) | 8 (30) | |

| Cerebral | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | - | |

| Other | 4 (5) | 2 (4) | 2 (7) | |

| . | Total . | Platelet count ≥1000 × 109/L . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No . | Yes . | |||

| N = 451 (%) . | n = 323 (72) . | n = 128 (28) . | ||

| Major bleeding | 27 (6) | 14 (4) | 13 (10) | .026∗ |

| Major bleeding site | ||||

| GI | 14 (52) | 7 (50) | 7 (54) | >.99∗ |

| Intracranial | 6 (22) | 3 (21) | 3 (23) | |

| Retroperitoneal | 1 (4) | - | 1 (8) | |

| Hematuria | - | - | - | |

| Heavy period | 1 (4) | 1 (7) | - | |

| Other | 5 (19) | 3 (21) | 2 (15) | |

| CRNMB | 43 (10) | 31 (10) | 12 (9) | >.99∗ |

| CRNMB site | ||||

| GI | 5 (12) | 4 (13) | 1 (8) | .89∗ |

| Intracranial | - | - | - | |

| Retroperitoneal | - | - | - | |

| Hematuria | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | - | |

| Heavy period | 5 (12) | 3 (10) | 2 (17) | |

| Other | 32 (74) | 23 (74) | 9 (75) | |

| Thrombosis | 82 (18) | 55 (17) | 27 (21) | .34∗ |

| Arterial | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 14 (17) | 13 (24) | 1 (4) | .17∗ |

| Stroke | 23 (28) | 15 (27) | 8 (30) | |

| Other | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | 1 (4) | |

| Venous | ||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 15 (18) | 11 (20) | 4 (15) | .22∗ |

| Pulmonary embolism | 9 (11) | 6 (11) | 3 (11) | |

| Splanchnic/abdominal | 12 (15) | 4 (7) | 8 (30) | |

| Cerebral | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | - | |

| Other | 4 (5) | 2 (4) | 2 (7) | |

GI, gastrointestinal.

Fisher's exact test.

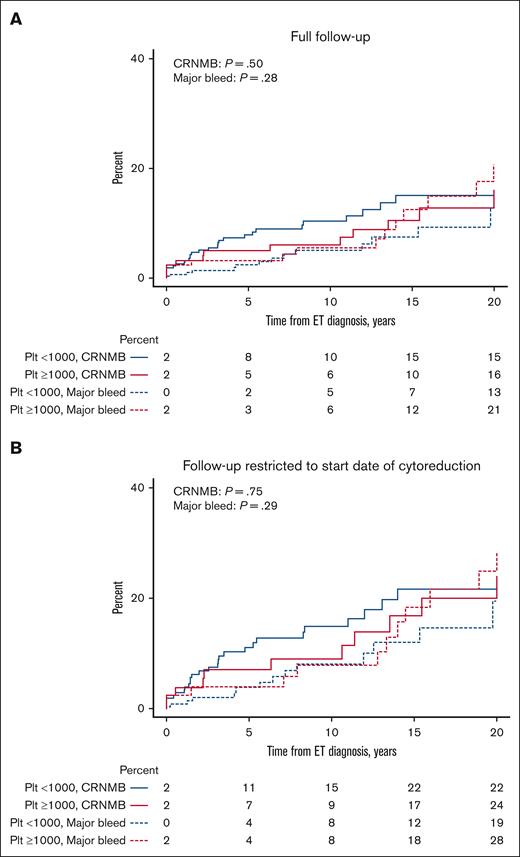

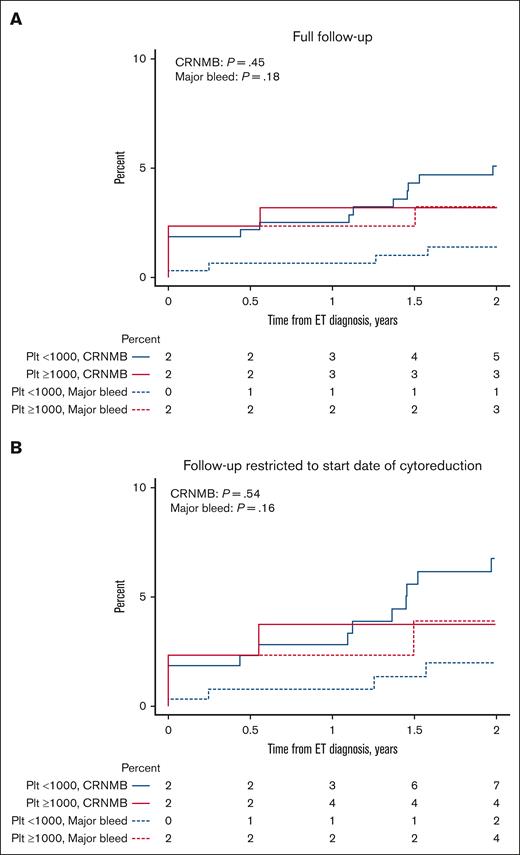

The cumulative incidence of major bleeds and CRNMBs, with death as a competing event, was not different between ExT and non-ExT patients (21% vs 13% [P = .28] for major bleed; 16% vs 15% [P = .50] for CRNMB; Figure 1A). When limiting follow-up to the start date of cytoreduction for patients treated with cytoreduction, there was also no difference in the cumulative incidence of bleeding (28% vs 19% [P = .29] for major bleed; 24% vs 22% [P = .75] for CRNMB; Figure 1B). Similarly, we found no differences in the 2-year cumulative incidence of major bleed and CRNMB between groups over full follow-up (3% vs 1% [P = .18] for major bleed; 3% vs 5% [P = .45] for CRNMB; Figure 2A) and when limiting follow-up to the start date of cytoreduction (4% vs 2% [P = .16] for major bleed; 4% vs 7% [P = .54] for CRNMB; Figure 2B). When using 1500 × 109/L as the platelet cutoff for ExT, we found no differences in the overall (10% vs 17% [P = .85] for major bleed; 17% vs 16% [P = .53] for CRNMB; supplemental Figure 1A) and 2-year cumulative incidence of major bleed and CRNMB (0% vs 2% [P = .48] for major bleed; 0% vs 5% [P = .27] for CRNMB; supplemental Figure 1B) between the groups.

Cumulative incidence of major bleeding and CRNMB in ExT and non-ExT patients with death as a competing event. (A) Full follow-up. (B) Follow-up restricted to the start date of cytoreduction. Plt, platelet.

Cumulative incidence of major bleeding and CRNMB in ExT and non-ExT patients with death as a competing event. (A) Full follow-up. (B) Follow-up restricted to the start date of cytoreduction. Plt, platelet.

Two-year cumulative incidence of major bleeding and CRNMB in ExT and non-ExT patients with death as a competing event. (A) Full follow-up. (B) Follow-up restricted to the start date of cytoreduction. Plt, platelet.

Two-year cumulative incidence of major bleeding and CRNMB in ExT and non-ExT patients with death as a competing event. (A) Full follow-up. (B) Follow-up restricted to the start date of cytoreduction. Plt, platelet.

Moreover, there was no difference in bleeding in ExT patients who were treated vs not treated with cytoreduction (24% vs 0% [P = .089] for major bleed; 15% vs 23% [P = .13] for CRNMB; supplemental Figure 2). Similar results were seen when only examining combined very low- and low-risk ExT patients. There was also no difference in bleeding between ExT and non-ExT patients who were not treated with cytoreduction (untreated or aspirin alone, 0% vs 5% [P = .30] for major bleed; 23% vs 18% [P = .60] for CRNMB; supplemental Figure 3).

There were 27 (21%) and 55 thrombotic events (17%) in the 128 ExT patients and 323 non-ExT patients, respectively. The cumulative incidence of thrombosis with death as a competing event was not different between ExT and non-ExT patients (28% vs 25%; P = .98; supplemental Figure 4A). There was also no difference in the 2-year cumulative incidence of thrombosis between the groups (9% vs 10%; P = .85; supplemental Figure 4B).

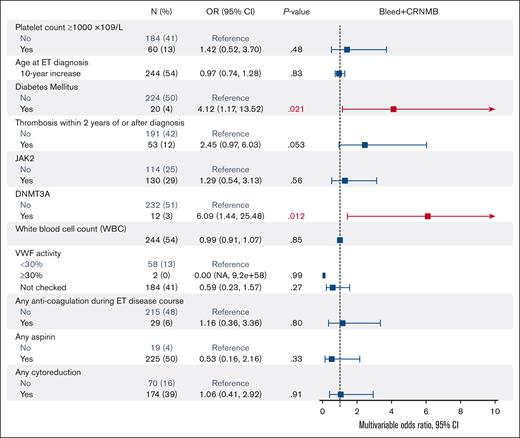

Risk factors for bleeding

We analyzed platelet count, WBC count, age at ET diagnosis, sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, driver (JAK2, CALR, and MPL) and nondriver mutations (ASXL1, DNMT3A, and TET2), history of thrombosis, thrombosis during disease course, VWF levels, and treatment during disease course (aspirin, anticoagulation, cytoreduction, and aspirin + cytoreduction) in univariate models. Diabetes mellitus (odds ratio [OR], 2.84; 95% CI, 1.23-6.14), thrombosis during disease course (OR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.50-4.81), anticoagulation during disease course (OR, 2.54; 95% CI, 1.19-5.13), and presence of a DNMT3A mutation (OR, 3.70; 95% CI, 1.20-10.0) were significantly associated with increased combined major bleeding and CRNMB (supplemental Table 2). In the multivariable analysis, we adjusted for these variables in addition to platelet count ≥1000 × 109/L, WBC count, age at ET diagnosis, first VWF activity, aspirin use, cytoreduction use, and JAK2 mutation status because these may contribute to the pathophysiology of bleeding. In the multivariable analysis, diabetes mellitus (hazard ratio [HR], 4.12; 95% CI, 1.17-13.52) and the DNMT3A mutation (HR, 6.09; 95% CI, 1.44-25.48) remained as significant risk factors for bleeding. Cytoreduction was not significantly associated with a lower rate of bleeding in the multivariable analysis (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.41-2.92; Figure 3). von Willebrand activity levels <30% were not significantly associated with bleeding, although the number of patients with von Willebrand levels <30% was small.

Multivariable model assessing the association of factors associated with major and clinically relevant non-major bleeding in ET patients.

Multivariable model assessing the association of factors associated with major and clinically relevant non-major bleeding in ET patients.

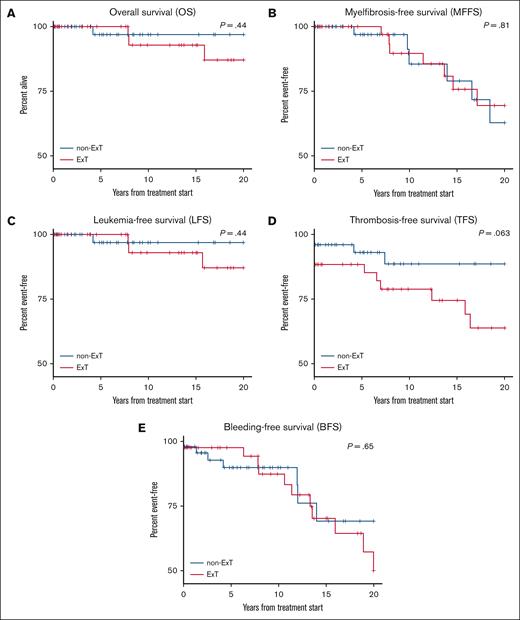

Progression and survival outcomes

We found no differences between ExT and non-ExT patients in overall survival (P = .44), myelofibrosis-free survival (P = .81), leukemia-free survival (P = .44), thrombosis-free survival (P = .063), and bleeding-free survival (P = .65; Figure 4). Up to 85% and 68% of ExT patients, compared with 89% and 67% of non-ExT patients, were alive at 10 and 20 years after ET diagnosis, respectively.

Kaplan-Meier analysis illustrating overall survival, myelofibrosis-free survival, leukemia-free survival, thrombosis-free survival, and bleeding-free survival in ExT and non-ExT patients. (A) Overall survival. (B) Myelofibrosis-free survival. (C) Leukemia-free survival. (D) Thrombosis-free survival. (E) Bleeding-free survival.

Kaplan-Meier analysis illustrating overall survival, myelofibrosis-free survival, leukemia-free survival, thrombosis-free survival, and bleeding-free survival in ExT and non-ExT patients. (A) Overall survival. (B) Myelofibrosis-free survival. (C) Leukemia-free survival. (D) Thrombosis-free survival. (E) Bleeding-free survival.

Discussion

In this retrospective study of 451 patients with ET, we analyzed the cumulative incidence of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with (platelet count ≥1000 × 109/L) and without ExT (platelet count <1000 × 109/L). Consistent with the literature, ExT patients were more likely to be younger, have a CALR mutation, and have lower R-IPSET scores.15-18 We found no significant difference in the 2-year or overall cumulative incidence of bleeding and thrombosis in ExT vs non-ExT patients with ET, even when controlling for the use of cytoreduction. We similarly found no differences in bleeding when using 1500 × 109/L as the platelet cutoff for ExT. Very low- and low-risk ExT patients were more likely to be cytoreduced and less likely to be treated with aspirin alone than non-ExT patients. The major risk factors for bleeding in this cohort included diabetes mellitus and the presence of a DNMT3A mutation. Thrombosis-free, myelofibrosis-free, leukemia-free, and overall survival were similar between ExT and non-ExT patients.

Our results suggest no significantly increased bleeding risk in patients with ET who present with ExT, as defined by a platelet count >1000 × 109/L. It is possible that this could be due to greater use of cytoreduction in patients with ExT. However, when restricting follow-up to the start date of cytoreduction, we found no differences in the overall and 2-year cumulative incidence of bleeding between ExT and non-ExT patients. Moreover, there was no difference in the cumulative incidence of bleeding in ExT patients who were treated vs not treated with cytoreduction. This result held when only examining combined very low- and low-risk ExT patients. This aligns with the results of a small study that showed similar major bleeding rates in 99 ExT patients who were treated vs not treated with cytoreduction (8% vs 4%; P = .52).33 There was also no difference in the cumulative incidence of bleeding between ExT and non-ExT patients who were not treated with cytoreduction (untreated or aspirin alone). Together, these results highlight the inherent similar bleeding rates in these 2 populations when platelet counts are not reduced. Cytoreduction was not significant in univariate or multivariable analyses assessing factors contributing to bleeding. Aspirin use was also balanced between the groups and used in most patients, suggesting that treatment with aspirin does not unmask greater bleeding in ExT patients. However, there was a trend toward a lesser percentage of ExT patients being treated with aspirin alone (20% vs 28%), in light of the finding from Alvarez-Larrán et al that aspirin use does not reduce thrombosis risk but increases bleeding risk in low-risk CALR patients with ET.34

Our findings add additional data to a body of mixed literature on ExT and bleeding. Two recent studies showed trends toward an increase in the crude incidence of bleeding in ExT patients. Tefferi et al and Gangat et al both found a nonsignificant increase of major bleeding in patients with ExT compared with those without (15% vs 10% [P = .16] and 15% vs 7% [P = .09]).17,19 Alvarez-Larrán et al found 5.4-fold higher odds of major bleeding in ExT patients taking antiplatelet therapy than ExT patients not taking antiplatelet therapy and non-ExT patients both taking and not taking antiplatelet therapy.35 However, Finazzi et al and Carrobio et al both found no difference in the rates of major bleeding in ExT vs non-ExT patients in retrospective studies with large sample sizes (for Finazzi et al, n = 1104; for Carobbio et al, n = 891).20,36 Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to add data on CRNMB, which contributes significantly to patient morbidity.

Because platelet count alone may be insufficient to predict bleeding, identifying risk factors for bleeding is significant, given its relatively high incidence rate. Bleeding risk factors are less clear than thrombotic risk factors and include leukocytosis, history of bleeding, aspirin, and AVWS.22,23,36,37 Although we did not have data on the history of bleeding, we identified diabetes mellitus and the presence of a DNMT3A mutation as risk factors for combined major bleeding and CRNMB in multivariable analysis. Diabetes mellitus has been associated with increased bleeding in the general population, potentially because of impaired wound healing, although this mechanism needs to be further explored in patients with ET.38 The association of the DNMT3A mutation and bleeding is novel because previous studies only analyzed its association with thrombosis. A recent study investigated the association of DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 nondriver mutations and thrombosis in patients with MPN and found the presence of ≥1 of these mutations posed a higher risk of thrombosis (OR, 6.3).39 We did not find an effect of aspirin treatment because of the overall small proportion of patients who were not treated with aspirin.

Our finding of no difference in the cumulative incidence of bleeding persisted despite ExT patients having significantly lower first VWF activity levels. This suggests that the relationship between bleeding and platelet counts may only partially be mediated by AVWS. Other factors may contribute both to the development of AVWS and how much AVWS predisposes to bleeding if developed. Recent studies found that platelet count at diagnosis, younger age, and the absence of cytoreduction were associated with a higher risk of AVWS.22,23 Our data set is limited because VWF levels were not systematically drawn in this retrospective review.

Overall, our findings suggest that ExT alone should not be an indication to start cytoreduction to reduce bleeding risk. The interplay between platelet count and bleeding risk is likely complex and individualized and depends on other variables including comorbidities, bleeding history, von Willebrand levels, antiplatelet/anticoagulant treatments, diabetes, and mutation status. Although our methods do not allow for us to find a platelet threshold at which bleeding risk increases in patients with ET, our study suggests that ExT patients with >1000 × 109/L and >1500 × 109/L platelets do not have an increased bleeding risk. However, our study does not rule out that bleeding risk increases at other thresholds. Consistent with other studies, we found no increased risk of thrombosis in ExT patients.17,19,20 Although we found no differences in survival outcomes, there has been some evidence that ExT patients may have lower overall survival and leukemia-free survival.19,40 We may not have captured this given our median of 12 years of follow-up in ExT patients.

We identified a relatively large population of patients with ET with granular data available on genomic sequencing, laboratory values, and outcomes including bleeding events. However, 88% of patients with ET in our study were White, limiting generalizability to more diverse populations. We may not have captured all bleeding events because some including heavy menses are less likely to be reported either by the patient or clinician. In addition, detecting incremental risk in bleeding at different platelet thresholds was not possible with our study due to its sample size; thus, further research is needed to determine whether there is a platelet level after which cytoreduction is indicated.21 We also only looked at platelet counts at diagnosis and did not account for changing platelet counts over time. However, to partially address this, we found no difference in bleeding when restricting follow-up to the start date of cytoreduction, but we cannot rule out that platelet changes during the disease course may also affect bleeding risk. We also may not have sufficient power to detect small but significant differences in bleeding rates.

In conclusion, we found no difference in the cumulative incidence of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with ET with ExT. Although this supports current guidelines, further research is needed to evaluate how AVWS and aspirin use contribute to bleeding in ExT patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the team supporting the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Hematologic Malignancies Data Repository and Massachusetts General Hospital Myeloproliferative Neoplasm databases.

This project was supported by the American Society of Hematology Hematology Opportunities for the Next Generation of Research Scientists award.

Authorship

Contribution: R.K.V., G.S.H., and J.H. designed the study; R.K.V. and A.C.H. performed medical record review; J.H., L.D.W., M.W., and A.E.M. collected data; C.J.K. curated the data for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Hematologic Malignancies Data Repository database; R.A.R., R.K.V., G.S.H., and J.H. analyzed the data; R.K.V. wrote the manuscript and had editorial support from G.S.H. and J.H; and all authors edited the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.J.A. reports consultancy fees from and being a current equity holder in private company, SeQure Dx. L.D.W. reports consultancy fees from AbbVie and Vertex, and membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committee for Sobi. M.S. reports membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees for Rigel, Novartis, Sierra Oncology, Kymera, and GlaxoSmithKline; other interests including graduate medical education activity in Haymarket Media, Clinical Care Options, Novartis, and Curis Oncology; and consultancy fees from Dedham group and Boston Consulting. D.J.D. reports honoraria from Pfizer, Incyte, Amgen, Takeda, Servier, Jazz, Kite, Blueprint, Autolus, Novartis, and Gilead, and research funding from AbbVie, Novartis, Blueprint, and GlycoMimetics. R.C.L. reports consultancy fees from Takeda Pharmaceuticals, bluebird bio, Qiagen, Sarepta Therapeutics, Verve Therapeutics, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committee for bluebird bio. M.R.L. reports research funding from AbbVie and Novartis, and honoraria from Jazz, Pfizer and Novartis. G.S.H. reports research funding from Incyte and MorphoSys; membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees for Keros, Pharmaxis, Pfizer, MorphoSys, Novartis, Protagonist, AbbVie, and Bristol Myers Squibb; and is current holder of stock options in a privately held company, Regeneron. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joan How, Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis St, Boston, MA 02115; email: jhow@bwh.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

G.S.H. and J.H. contributed equally to this study.

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Joan How (jhow@bwh.harvard.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.