Key Points

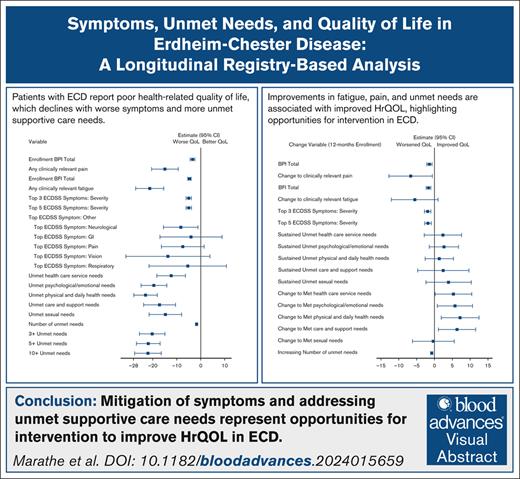

Patients with ECD report diminished HrQOL associated with burden of symptomatology and unmet supportive care needs.

Improvement in fatigue, pain, and unmet needs are associated with improved HrQOL, highlighting opportunities for intervention in ECD.

Visual Abstract

Measurement of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and health-related quality of life (HrQOL) are crucial for comprehensive, patient-centered cancer care. Both PROs and HrQOL have been understudied in patients with Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD), a rare cancer with protean manifestations, dense symptomatology, and frequent diagnostic delay. We sought to evaluate the longitudinal evolution of symptom burden and unmet supportive care needs in patients with ECD, and to identify associations between these PROs and HrQOL. A registry-based cohort of patients with ECD completed a PRO battery including the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) and other validated PRO measures. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the distribution of PROs and FACT-G scores; PROs were modeled by univariable linear regression with FACT-G total score as the dependent variable at (1) registry enrollment and (2) 12-month time points. Changes in FACT-G total score (the difference between the 12-month and enrollment scores) were correlated with changes in PROs using univariable linear regression analysis. In 158 patients, mean total FACT-G was 70.8, lower than observed across multiple cancer cohorts. Higher levels of pain and fatigue, presence of neurologic symptoms, and greater number of unmet needs were all associated with worse HrQOL. Improvement in pain, fatigue, and unmet needs over 12 months was significantly associated with improvement in HrQOL. In patients with ECD, HrQOL is substantially diminished, even when considering other patients with cancer. Mitigation of symptoms and addressing unmet supportive care needs represent opportunities for intervention to improve HrQOL in ECD.

Introduction

Disease symptoms are measurable physical or psychological manifestations of illness that patients report. Health-related quality of life (HrQOL) is a broad, multidimensional concept encompassing a person’s appraisal of their life satisfaction considering physical, social, emotional, functional, and other aspects of well-being.1 The relationship between symptom presence, severity, and overall HrQOL are variable; however, associations between symptomatology and HrQOL within specific diseases can inform patient-centered care. Histiocytic neoplasms (HNs) are rare hematologic malignancies characterized by the abnormal accumulation of monocyte, macrophage, or dendritic lineage cells in virtually any tissue in the body, leading to a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes.2 Severity ranges from self-resolving to life-threatening with affected sites including the bone, skin, central nervous system, liver, spleen, bone marrow, and lungs. Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) is a rare subtype of HN of which only ∼1500 total cases have been described worldwide.3

Historically, there were no standard treatments for ECD, resulting in significant morbidity, guarded prognoses, and high mortality rates within years of diagnosis.3 The treatment landscape transformed with the discovery of BRAF and other MAPK pathway mutations in ECD and other HNs. This discovery led to the evaluation and implementation of BRAF4-14 and MEK15-19 inhibitor therapies in HNs. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of vemurafenib for patients with ECD with a BRAF mutation in 2017, followed by the approval of cobimetinib for the treatment of all adult HNs in 2022.20 With the growing use of targeted therapies, mortality from ECD has fallen dramatically, reaching almost 0 in the setting of chronic treatment.20 Consequently, there is now a growing population of adult survivors living with ECD as a chronic disease requiring lifelong therapy. This new era of equilibrium of treatment and improved survival has renewed the importance of addressing symptoms, unmet needs, and HrQOL for patients managing ECD long term.

Traditionally, clinician-based assessments have been the primary method of ascertaining patient symptoms, unmet needs, and HrQOL. However, the growing adoption of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) has increased patient engagement and improved quality of care, especially for patients with rare diseases such as ECD who often endure heterogeneous and poorly understood symptoms.21,22 Assessment of HrQOL has been associated with enhanced communication between patients and providers and more effective symptom management.23 Recognizing the value of patient-elicited symptoms, the National Cancer Institute and FDA now recommend the use of PROs as end points in all clinical trials for cancer.24-26

Previous research indicates that fatigue and pain are prevalent and severe symptoms in patients with ECD and interfere with daily living; these symptoms endure despite lower disease burden or radiologic treatment response.27,28 Analysis of overall HrQOL in ECD and its associated symptoms and clinical features has, to our knowledge, not been reported. Moreover, there has been no longitudinal observation of PROs in ECD, their change over time, and whether HrQOL is affected by change in symptomatology. Limited research has also shown an abundance of unmet supportive care needs among caregivers of patients with ECD and other HNs, but neither unmet needs in patients with ECD, nor the association between unmet needs and HrQOL, have been explored.29,30

This study aims to advance the current knowledge on PROs in ECD by examining HrQOL in a large cohort of adult patients with ECD and its association with physical symptoms and unmet supportive care needs. We hypothesized that greater fatigue and pain, as well as greater unmet needs, would be associated with reduced HrQOL; we further hypothesized that longitudinal PRO analysis would demonstrate that increase and reduction in symptoms and unmet needs would be associated with worsening or improvement, respectively, in HrQOL. Ultimately, our goal is to identify opportunities to improve care for patients living with ECD.

Methods

Design

This study used an institutional review board (IRB) approved registry maintained at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK; IRB number 17-516; NCT03329274). The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and clinical data were obtained with patient-informed consent and regulatory approval by the IRB of MSK. This study was conducted in keeping with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.31 All clinical and patient-reported data from this registry are collected and stored in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web-based platform.

Participants

Participants with a confirmed diagnosis of ECD or other HNs were recruited from the Departments of Neurology and Medicine at MSK or referred from the ECD Global Alliance or Histiocytosis Association (patient advocacy groups dedicated to ECD and HN, respectively). Interested and eligible participants provided written or electronic informed consent to enroll in the registry. Registry patients with ECD who were fluent in English, aged ≥18 years, and treated for their disease in the United States or Canada provided additional consent to complete self-reported PRO assessments. Data collected from 2018 to 2023 were analyzed for this study.

Clinical characteristics

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are curated into the comprehensive registry database. For this study, sex, age at ECD diagnosis, duration of diagnosed ECD illness, medical comorbidities, sites of disease involvement, and BRAFV600 mutational status were analyzed.

PRO measures

PRO assessments were performed virtually through the REDCap platform at the time of enrollment into the study and then at 6 months and 12 months. The primary outcome of interest was HrQOL as measured by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) version 4.32 This is a 27-item instrument using 5-point Likert-type scales. The survey assesses the previous 7 days with subscales in 4 HrQOL domains: physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being, and functional well-being. The FACT-G total score (range, 0-108) is the sum of subscale scores and reflects overall HrQOL, with higher scores indicating better self-reported HrQOL. There is abundant normative data from general population samples and from patients with cancer, allowing for the interpretation of scores in reference to diverse clinical populations.33 A 4- to 7-point difference in total FACT-G score is consistent with a meaningful clinical difference.32,34

To comprehensively evaluate symptom burden, we included the Erdheim-Chester Disease Symptom Scale (ECD-SS),28 Brief Pain Inventory (BPI),35 Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI),36 and Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS).37 The ECD-SS is a disease-specific symptom inventory, with a total of 63 symptoms, from which participants endorse and rate the severity of their 3 to 5 most salient symptoms, from 0 to 10, using a numeric rating scale (NRS),28 yielding a continuous score with higher scores indicating worse symptom severity. The BPI and BFI are validated measures used to assess the severity and impact of pain and fatigue, respectively, in patients with cancer.35,36 The BPI38-42 is an 11-item questionnaire with 0 to 10 NRS items related to pain with higher scores indicating worse pain. The measure generates composite continuous scores of (1) pain severity, (2) pain interference, and (3) overall composite pain. The BFI is a 9-item instrument that uses an 11-point NRS to measure fatigue, with higher scores indicating worse fatigue. Each item is scored from 0 to 10. The measure generates composite continuous scores for (1) fatigue severity, (2) fatigue interference, and (3) overall composite fatigue. The dichotomous presence of clinically relevant pain and fatigue, as we have published previously, is defined as having at least 1 BPI or 1 BFI item scored ≥4, reflecting moderate to severe symptoms.43,44 To measure unmet supportive care needs, we administered the SCNS Short Form 34, a well-validated instrument assessing the perceived needs of people diagnosed with cancer. Thirty-four items are mapped to the following 5 domains: psychological, health system, physical/daily living, patient care/support, and sexuality. Participants indicate via Likert scale responses whether needs are strongly unmet to strongly met. Needs were dichotomized in each of the 5 domains to met vs unmet. The needs of a domain were unmet if any item specific to that domain was ranked as a moderate or high need.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations (SDs) were used to characterize the distribution of HrQOL and PROs in the cohort. To test the associations between specific PROs and total FACT-G score, unadjusted linear regression models were performed. Specifically, BPI total and BPI clinically relevant pain, BFI total and BFI clinically relevant fatigue, top ECD-SS symptom type and top 3 and 5 ECD-SS symptom severities, unmet needs per SCNS domain, and number of unmet needs were each univariably associated with FACT-G total score using linear regression modeling. These models were conducted twice for each association of interest: once using enrollment data and again using 12-month data. These models resulted in estimates at 1 point in time at which, for example, a 1-unit increase in symptom severity in the cohort was associated with the corresponding difference in HrQOL on average as measured by the FACT-G score at that same point in time. In addition, unadjusted linear regression analysis was also performed to correlate changes in the FACT-G total score over time (calculated as the difference between the 12-month and enrollment scores) with changes in PROs, including BPI, BFI, ECD-SS, and SCNS unmet needs, over the same period. These models resulted in change estimates per correlation, for which, for example, a 1-unit increase in the change in symptom severity over time (difference: 12-months minus enrollment) was associated with the corresponding change estimate in HrQOL on average as measured by total FACT-G score over time (difference: 12-months minus enrollment). Post hoc multivariable models were performed, adjusting for potential confounders including age at ECD diagnosis, brain/parenchymal site involvement, and length of diagnosed ECD illness. Tests were 2-sided with a statistical significance level of <.05. Analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4.45

Results

A total of 159 participants with a biopsy-confirmed diagnosis of ECD, or ECD mixed with Langerhans cell histiocytosis or Rosai-Dorfman disease, were enrolled in the study and completed at least 1 PRO survey at the time of enrollment (Table 1). The study cohort was 59% male, with an average age of 51.2 years (range, 8.1-76.9) at ECD diagnosis, and 55.3 years (range, 18.9-80) at the time of enrollment into the study. The average duration of diagnosed ECD illness was 6.5 years (range, 0.08-38.8). Sites of disease varied, with 92% of patients having lesions of the bone, 68% involving the nervous system, and 50% with retroperitoneum involvement. Overall, 57% of patients had ECD with a BRAFV600E mutation; and 58% of patients were actively receiving targeted therapy at the time of enrollment whereas 33% were not undergoing any treatment.

Characteristics of patients with ECD completing PRO surveys at enrollment

| Variable . | Category . | n . | % . | Median . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at ECD diagnosis | y | 159 | 100 | 52.9 | 51.2 | 12.3 | 8.1 | 76.9 |

| Age at enrollment | y | 159 | 100 | 56.2 | 55.3 | 12.1 | 18.9 | 80 |

| Diagnosis | ECD | 139 | 87 | |||||

| Mixed ECD/LCH | 15 | 9 | ||||||

| Mixed ECD/RDD | 5 | 3 | ||||||

| Sex | Female | 65 | 41 | |||||

| Male | 94 | 59 | ||||||

| Length of undiagnosed ECD illness | y | 159 | 100 | 0.83 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 0 | 20.6 |

| Length of diagnosed ECD illness | y | 159 | 100 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 6 | 0.08 | 38.8 |

| Site of disease | Bone | 147 | 92 | |||||

| Neurologic | 108 | 68 | ||||||

| Brain/Parenchyma | 83 | 52 | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 73 | 46 | ||||||

| Pulmonary | 28 | 18 | ||||||

| Retroperitoneum | 80 | 50 | ||||||

| Abdomen | 28 | 18 | ||||||

| Skin | 40 | 25 | ||||||

| Lymph node | 13 | 8 | ||||||

| Other | 22 | 14 | ||||||

| Hypertension | No | 83 | 52 | |||||

| Yes | 75 | 47 | ||||||

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Diabetes | No | 134 | 84 | |||||

| Yes | 24 | 15 | ||||||

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Mutational status | BRAFV600E mutant | 90 | 57 | |||||

| With JAK2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| With RAS | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| BRAFV600E wild type | 39 | 25 | ||||||

| CSF1R | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| JAK2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| ARAF | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| MAP2K1 | 10 | 6 | ||||||

| RAS/RAF | 5 | 4 | ||||||

| Non-V600E BRAF | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Not sequenced | 6 | 4 | ||||||

| Treatment at enrollment | None | 52 | 33 | |||||

| Conventional | 15 | 9 | ||||||

| Targeted | 92 | 58 | ||||||

| Treatment at 12 months | None | 28 | 24 | |||||

| Conventional | 9 | 8 | ||||||

| Targeted | 78 | 49 | ||||||

| Other∗ | 3 | 2 | ||||||

| Unknown | 41 | 25 |

| Variable . | Category . | n . | % . | Median . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at ECD diagnosis | y | 159 | 100 | 52.9 | 51.2 | 12.3 | 8.1 | 76.9 |

| Age at enrollment | y | 159 | 100 | 56.2 | 55.3 | 12.1 | 18.9 | 80 |

| Diagnosis | ECD | 139 | 87 | |||||

| Mixed ECD/LCH | 15 | 9 | ||||||

| Mixed ECD/RDD | 5 | 3 | ||||||

| Sex | Female | 65 | 41 | |||||

| Male | 94 | 59 | ||||||

| Length of undiagnosed ECD illness | y | 159 | 100 | 0.83 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 0 | 20.6 |

| Length of diagnosed ECD illness | y | 159 | 100 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 6 | 0.08 | 38.8 |

| Site of disease | Bone | 147 | 92 | |||||

| Neurologic | 108 | 68 | ||||||

| Brain/Parenchyma | 83 | 52 | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 73 | 46 | ||||||

| Pulmonary | 28 | 18 | ||||||

| Retroperitoneum | 80 | 50 | ||||||

| Abdomen | 28 | 18 | ||||||

| Skin | 40 | 25 | ||||||

| Lymph node | 13 | 8 | ||||||

| Other | 22 | 14 | ||||||

| Hypertension | No | 83 | 52 | |||||

| Yes | 75 | 47 | ||||||

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Diabetes | No | 134 | 84 | |||||

| Yes | 24 | 15 | ||||||

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Mutational status | BRAFV600E mutant | 90 | 57 | |||||

| With JAK2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| With RAS | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| BRAFV600E wild type | 39 | 25 | ||||||

| CSF1R | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| JAK2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| ARAF | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| MAP2K1 | 10 | 6 | ||||||

| RAS/RAF | 5 | 4 | ||||||

| Non-V600E BRAF | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Not sequenced | 6 | 4 | ||||||

| Treatment at enrollment | None | 52 | 33 | |||||

| Conventional | 15 | 9 | ||||||

| Targeted | 92 | 58 | ||||||

| Treatment at 12 months | None | 28 | 24 | |||||

| Conventional | 9 | 8 | ||||||

| Targeted | 78 | 49 | ||||||

| Other∗ | 3 | 2 | ||||||

| Unknown | 41 | 25 |

LCH, Langerhans cell histiocytosis; Max, maximum; Min, minimum; RDD, Rosai-Dorfman disease.

Other regimens included pembrolizumab, imatinib/anakinra, and pexidartinib.

HrQOL and PROs distributions

At enrollment, 158 patients completed the FACT-G; at 12 months, 126 patients completed this assessment (Table 2). Of a maximum FACT-G total score of 108, the mean ± SD total FACT-G score was 70.8 ± 19 at enrollment and 75.2 ± 16.8 at 12 months. The FACT-G domain with the lowest average score at both time points was functional well-being, with an average score of 15.7 ± 6.7 and 16.8 ± 6 of a possible total of 28 at enrollment and at 12 months, respectively. The FACT-G domain with the highest average score at enrollment was social well-being (average, 19.7 ± 6.1 of a possible total score of 28) whereas the FACT-G domain with the highest average score at 12 months was physical well-being (average, 20.5 ± 5.6 of a possible total score of 28).

PRO distributions at enrollment and 12-month time points

| PRO assessment . | Enrollment . | 12-months . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | Median . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . | n . | % . | Median . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . | |

| FACT-G: physical well-being | 158 | 99.4 | 20 | 18.8 | 6.5 | 0 | 28 | 126 | 79.2 | 22 | 20.5 | 5.6 | 5 | 28 |

| FACT-G: emotional well-being | 158 | 99.4 | 17 | 16.6 | 4.5 | 3 | 24 | 126 | 79.2 | 18 | 17.6 | 4 | 4 | 24 |

| FACT-G: social well-being | 158 | 99.4 | 21 | 19.7 | 6.1 | 1 | 28 | 126 | 79.2 | 21 | 20.2 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 28 |

| FACT-G: functional well-being | 158 | 99.4 | 15.6 | 15.7 | 6.7 | 0 | 28 | 126 | 79.2 | 17 | 16.8 | 6 | 0 | 28 |

| FACT-G: total | 158 | 99.4 | 74.3 | 70.8 | 19 | 22 | 105 | 126 | 79.2 | 77 | 75.2 | 16.8 | 31 | 104 |

| BPI: severity | 154 | 96.9 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 0 | 8 | 123 | 77.4 | 0 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 0 | 8 |

| BPI: interference | 154 | 96.9 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 123 | 77.4 | 0 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 0 | 10 |

| BPI: total | 154 | 96.9 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0 | 8.9 | 124 | 78 | 0 | 2 | 2.6 | 0 | 9.1 |

| Clinically relevant pain | 75 | 49 | 52 | 42 | ||||||||||

| BFI: severity | 154 | 96.9 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 0 | 9.3 | 122 | 76.7 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 0 | 9 |

| BFI: interference | 154 | 96.9 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 0 | 10 | 122 | 76.7 | 2.9 | 3 | 3.1 | 0 | 10 |

| BFI: total | 154 | 96.9 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3 | 0 | 9.8 | 122 | 76.7 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3 | 0 | 9.6 |

| Clinically relevant fatigue | 110 | 71 | 72 | 59 | ||||||||||

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 154 | 96.9 | 7 | 6.7 | 2.2 | 0 | 10 | 122 | 76.7 | 6 | 5.5 | 2.6 | 0 | 10 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 154 | 96.9 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 2.1 | 0 | 10 | 122 | 76.7 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 0 | 10 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: other | 52 | 33 | 30 | 34 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: neurologic | 58 | 37 | 34 | 39 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: GI | 10 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: pain | 27 | 17 | 11 | 13 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: vision | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: respiratory | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Unmet health care service needs | 58 | 38 | 33 | 28 | ||||||||||

| Unmet psychological/emotional needs | 90 | 58 | 56 | 45 | ||||||||||

| Unmet physical and daily health needs | 90 | 57 | 63 | 50 | ||||||||||

| Unmet care and support needs | 37 | 24 | 19 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Unmet sexual needs | 37 | 25 | 26 | 22 | ||||||||||

| No. of unmet needs | 159 | 100 | 4 | 7 | 7.4 | 0 | 29 | 125 | 78.6 | 3 | 5 | 6.2 | 0 | 31 |

| ≥3 unmet needs | 100 | 63 | 64 | 51 | ||||||||||

| ≥5 unmet needs | 79 | 50 | 49 | 39 | ||||||||||

| ≥10 unmet needs | 48 | 30 | 26 | 21 | ||||||||||

| PRO assessment . | Enrollment . | 12-months . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | Median . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . | n . | % . | Median . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . | |

| FACT-G: physical well-being | 158 | 99.4 | 20 | 18.8 | 6.5 | 0 | 28 | 126 | 79.2 | 22 | 20.5 | 5.6 | 5 | 28 |

| FACT-G: emotional well-being | 158 | 99.4 | 17 | 16.6 | 4.5 | 3 | 24 | 126 | 79.2 | 18 | 17.6 | 4 | 4 | 24 |

| FACT-G: social well-being | 158 | 99.4 | 21 | 19.7 | 6.1 | 1 | 28 | 126 | 79.2 | 21 | 20.2 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 28 |

| FACT-G: functional well-being | 158 | 99.4 | 15.6 | 15.7 | 6.7 | 0 | 28 | 126 | 79.2 | 17 | 16.8 | 6 | 0 | 28 |

| FACT-G: total | 158 | 99.4 | 74.3 | 70.8 | 19 | 22 | 105 | 126 | 79.2 | 77 | 75.2 | 16.8 | 31 | 104 |

| BPI: severity | 154 | 96.9 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 0 | 8 | 123 | 77.4 | 0 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 0 | 8 |

| BPI: interference | 154 | 96.9 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 123 | 77.4 | 0 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 0 | 10 |

| BPI: total | 154 | 96.9 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0 | 8.9 | 124 | 78 | 0 | 2 | 2.6 | 0 | 9.1 |

| Clinically relevant pain | 75 | 49 | 52 | 42 | ||||||||||

| BFI: severity | 154 | 96.9 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 0 | 9.3 | 122 | 76.7 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 0 | 9 |

| BFI: interference | 154 | 96.9 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 0 | 10 | 122 | 76.7 | 2.9 | 3 | 3.1 | 0 | 10 |

| BFI: total | 154 | 96.9 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3 | 0 | 9.8 | 122 | 76.7 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3 | 0 | 9.6 |

| Clinically relevant fatigue | 110 | 71 | 72 | 59 | ||||||||||

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 154 | 96.9 | 7 | 6.7 | 2.2 | 0 | 10 | 122 | 76.7 | 6 | 5.5 | 2.6 | 0 | 10 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 154 | 96.9 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 2.1 | 0 | 10 | 122 | 76.7 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 0 | 10 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: other | 52 | 33 | 30 | 34 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: neurologic | 58 | 37 | 34 | 39 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: GI | 10 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: pain | 27 | 17 | 11 | 13 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: vision | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Top ECD-SS symptom: respiratory | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Unmet health care service needs | 58 | 38 | 33 | 28 | ||||||||||

| Unmet psychological/emotional needs | 90 | 58 | 56 | 45 | ||||||||||

| Unmet physical and daily health needs | 90 | 57 | 63 | 50 | ||||||||||

| Unmet care and support needs | 37 | 24 | 19 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Unmet sexual needs | 37 | 25 | 26 | 22 | ||||||||||

| No. of unmet needs | 159 | 100 | 4 | 7 | 7.4 | 0 | 29 | 125 | 78.6 | 3 | 5 | 6.2 | 0 | 31 |

| ≥3 unmet needs | 100 | 63 | 64 | 51 | ||||||||||

| ≥5 unmet needs | 79 | 50 | 49 | 39 | ||||||||||

| ≥10 unmet needs | 48 | 30 | 26 | 21 | ||||||||||

GI, gastrointestinal.

A total of 154 patients completed the BPI and BFI at enrollment; at 12 months, 124 patients completed the BPI and 122 completed the BFI. At enrollment, 75 patients (49%) completing these surveys reported clinically relevant pain and 110 (71%) reported clinically relevant fatigue. At 12 months, these numbers decreased to 52 (42%) reporting clinically relevant pain and 72 (59%) reporting clinically relevant fatigue.

A total of 154 patients completed the ECD-SS at enrollment and 122 patients completed this scale at 12 months. The most endorsed symptom category at both time points was neurologic; of those completing the survey, it was scored as the top symptom by 58 patients (37%) at enrollment and 34 patients (39%) at 12 months. The mean ± SD severity of the top worst 3 symptoms was 6.7 ± 2.2 and 5.5 ± 2.6 of a possible total score of 10 at enrollment and at 12 months, respectively.

A total of 159 patients completed the SCNS unmet needs survey at enrollment; 125 patients completed this survey at 12 months. Unmet physical/daily health needs and unmet psychological/emotional needs were the 2 most frequently reported at both time points (57% and 58% of patients reported these unmet needs, respectively, at enrollment, whereas 50% and 45%, respectively, reported them at 12 months). The mean ± SD number of unmet needs per patient was 7 ± 7.4 at enrollment and 5 ± 6.2 at 12 months; ∼50% of patients had ≥5 unmet needs at enrollment, and ≥3 unmet needs at 12 months.

Associations between PROs and HrQOL

Higher levels of pain, fatigue, and unmet needs were all significantly associated with lower HrQOL at both enrollment and 12 months (Table 3). At enrollment, clinically relevant pain and fatigue showed strong associations with decreased HrQOL (BPI estimate, −14.83 [95% confidence interval (CI), −20.47 to −9.19]; BFI estimate: −21.25 [95% CI, −27.09 to −15.41]). These associations remained consistent at 12 months. At enrollment, unmet needs in any domain were significantly associated with a lower HrQOL with the strongest association seen for unmet physical/daily health needs (estimate, −22.99; 95% CI, −27.88 to −18.11). Increasing number of unmet needs at enrollment was also associated with decreased HrQOL with the strongest association seen for patients with ≥10 unmet needs (estimate, −22.02; 95% CI, −27.54 to −16.50). These associations remained consistent at 12 months.

Associations between symptoms/unmet needs and HrQOL at enrollment and 12-month time points

| Enrollment variable . | Enrollment . | 12 months . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | Estimate∗ . | 95% CI . | P value . | n . | Estimate∗ . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Enrollment BPI total | 153 | −3.42 | −4.41 to −2.42 | <.0001 | 124 | −2.91 | −3.93 to −1.88 | <.0001 |

| Any clinically relevant pain | 153 | −14.83 | −20.47 to −9.19 | <.0001 | 124 | −10.86 | −16.66 to −5.06 | .0003 |

| Enrollment BFI total | 153 | −4.71 | −5.42 to −4.01 | <.0001 | 122 | −3.43 | −4.23 to −2.64 | <.0001 |

| Any clinically relevant fatigue | 153 | −21.25 | −27.09 to −15.41 | <.0001 | 122 | −16.87 | −22.28 to −11.45 | <.0001 |

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 153 | −5.00 | −6.12 to −3.88 | <.0001 | 122 | −4.15 | −5.07 to −3.24 | <.0001 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 153 | −5.02 | −6.20 to −3.85 | <.0001 | 122 | −4.28 | −5.27 to −3.29 | <.0001 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: other | 157 | Ref | — | — | 125 | Ref | — | — |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: neurologic | 157 | −8.33 | −15.50 to −1.16 | .02 | 125 | −7.30 | −14.42 to −0.18 | .04 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: GI | 157 | −4.06 | −16.98 to 8.85 | .54 | 125 | −1.23 | −15.58 to 13.11 | .87 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: pain | 157 | −7.46 | −16.35 to 1.43 | .10 | 125 | −4.98 | −13.43 to 3.48 | .25 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: vision | 157 | −13.68 | −31.18 to 3.82 | .12 | 125 | 1.78 | −13.76 to 17.32 | .82 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: respiratory | 157 | −5.43 | −21.55 to 10.69 | .51 | 125 | 5.78 | −9.76 to 21.32 | .46 |

| Unmet health care service needs | 153 | −12.31 | −18.26 to −6.36 | <.0001 | 120 | −17.32 | −23.41 to −11.22 | <.0001 |

| Unmet psychological/emotional needs | 155 | −19.54 | −24.86 to −14.21 | <.0001 | 124 | −17.88 | −23.05 to −12.72 | <.0001 |

| Unmet physical and daily health needs | 157 | −22.99 | −27.88 to −18.11 | <.0001 | 125 | −16.63 | −21.84 to −11.41 | <.0001 |

| Unmet care and support needs | 152 | −17.15 | −23.80 to −10.49 | <.0001 | 123 | −14.94 | −22.87 to −7.01 | .0003 |

| Unmet sexual needs | 150 | −14.76 | −21.53 to −8.00 | <.0001 | 119 | −11.32 | −18.45 to −4.20 | .002 |

| No. of unmet needs | 158 | −1.71 | −2.01 to −1.41 | <.0001 | 125 | −1.90 | −2.25 to −1.54 | <.0001 |

| ≥3 unmet needs | 158 | −20.24 | −25.55 to −14.92 | <.0001 | 125 | −20.91 | −25.61 to −16.21 | <.0001 |

| ≥5 unmet needs | 158 | −21.86 | −26.77 to −16.95 | <.0001 | 125 | −21.44 | −26.25 to −16.63 | <.0001 |

| ≥10 unmet needs | 158 | −22.02 | −27.54 to −16.50 | <.0001 | 125 | −23.45 | −29.54 to −17.35 | <.0001 |

| Enrollment variable . | Enrollment . | 12 months . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | Estimate∗ . | 95% CI . | P value . | n . | Estimate∗ . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Enrollment BPI total | 153 | −3.42 | −4.41 to −2.42 | <.0001 | 124 | −2.91 | −3.93 to −1.88 | <.0001 |

| Any clinically relevant pain | 153 | −14.83 | −20.47 to −9.19 | <.0001 | 124 | −10.86 | −16.66 to −5.06 | .0003 |

| Enrollment BFI total | 153 | −4.71 | −5.42 to −4.01 | <.0001 | 122 | −3.43 | −4.23 to −2.64 | <.0001 |

| Any clinically relevant fatigue | 153 | −21.25 | −27.09 to −15.41 | <.0001 | 122 | −16.87 | −22.28 to −11.45 | <.0001 |

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 153 | −5.00 | −6.12 to −3.88 | <.0001 | 122 | −4.15 | −5.07 to −3.24 | <.0001 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 153 | −5.02 | −6.20 to −3.85 | <.0001 | 122 | −4.28 | −5.27 to −3.29 | <.0001 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: other | 157 | Ref | — | — | 125 | Ref | — | — |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: neurologic | 157 | −8.33 | −15.50 to −1.16 | .02 | 125 | −7.30 | −14.42 to −0.18 | .04 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: GI | 157 | −4.06 | −16.98 to 8.85 | .54 | 125 | −1.23 | −15.58 to 13.11 | .87 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: pain | 157 | −7.46 | −16.35 to 1.43 | .10 | 125 | −4.98 | −13.43 to 3.48 | .25 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: vision | 157 | −13.68 | −31.18 to 3.82 | .12 | 125 | 1.78 | −13.76 to 17.32 | .82 |

| Top ECD-SS symptom: respiratory | 157 | −5.43 | −21.55 to 10.69 | .51 | 125 | 5.78 | −9.76 to 21.32 | .46 |

| Unmet health care service needs | 153 | −12.31 | −18.26 to −6.36 | <.0001 | 120 | −17.32 | −23.41 to −11.22 | <.0001 |

| Unmet psychological/emotional needs | 155 | −19.54 | −24.86 to −14.21 | <.0001 | 124 | −17.88 | −23.05 to −12.72 | <.0001 |

| Unmet physical and daily health needs | 157 | −22.99 | −27.88 to −18.11 | <.0001 | 125 | −16.63 | −21.84 to −11.41 | <.0001 |

| Unmet care and support needs | 152 | −17.15 | −23.80 to −10.49 | <.0001 | 123 | −14.94 | −22.87 to −7.01 | .0003 |

| Unmet sexual needs | 150 | −14.76 | −21.53 to −8.00 | <.0001 | 119 | −11.32 | −18.45 to −4.20 | .002 |

| No. of unmet needs | 158 | −1.71 | −2.01 to −1.41 | <.0001 | 125 | −1.90 | −2.25 to −1.54 | <.0001 |

| ≥3 unmet needs | 158 | −20.24 | −25.55 to −14.92 | <.0001 | 125 | −20.91 | −25.61 to −16.21 | <.0001 |

| ≥5 unmet needs | 158 | −21.86 | −26.77 to −16.95 | <.0001 | 125 | −21.44 | −26.25 to −16.63 | <.0001 |

| ≥10 unmet needs | 158 | −22.02 | −27.54 to −16.50 | <.0001 | 125 | −23.45 | −29.54 to −17.35 | <.0001 |

Estimate interpretation: a 1-unit increase in enrollment symptom is associated on average with this change in total FACT-G score points. For example, a patient with an enrollment BPI total score of 6 will have, on average, a lower total FACT-G score at enrollment of 3.42 points than a patient with an enrollment BPI total score of 5. Another example: a patient with unmet health care service needs at 12 months will have, on average, a lower total FACT-G score at 12-months of 17.32 points than a patient with met health care service needs at 12 months.

From the ECD-SS, worse overall severity of top 3 and top 5 symptoms was significantly associated with worse HrQOL at enrollment (estimate for top 3 symptom severity, −5.00; 95% CI, −6.12 to −3.88) and 12 months (estimate for top 3 symptom severity, −4.15; 95% CI, −5.07 to −3.24). The presence of a neurologic symptom as the worst disease-related symptom was associated with worse HrQOL at enrollment (estimate, −8.33; 95% CI, −15.50 to −1.16) and 12 months (estimate, −7.30; 95% CI, −14.42 to −0.18). Multivariable analyses adjusting for age at ECD diagnosis, duration of diagnosed ECD illness, and presence of brain or parenchymal involvement are shown in supplemental Table 1 and demonstrate that, overall, these associations remain negligibly affected after adjustment.

Longitudinal analysis (Table 4) demonstrated that reductions in pain, both in total BPI scores and the shift from clinically relevant pain to its absence, were significantly associated with improved HrQOL (estimate for BPI total change, −1.42; 95% CI, −2.14 to −0.70). Similarly, a reduction in fatigue, as reflected by total BFI scores, was significantly associated with improvement in HrQOL (estimate for BFI total change, −1.69; 95% CI, −2.36 to −1.02). Reduction in ECD-SS symptom burden was significantly associated with improvement in HrQOL (top 3 estimate, −1.92; 95% CI, −2.82 to −1.03). Furthermore, meeting previously unmet needs in any category, except sexual needs, was significantly associated with improved HrQOL. Increasing number of any unmet needs was associated with reduction in HrQOL (estimate, −0.79; 95% CI, −1.07 to −0.51). Analyses adjusting for age at ECD diagnoses, length of diagnosed ECD illness, and presence of brain or parenchymal disease demonstrate that overall, these associations remain negligibly affected after adjustment (supplemental Table 2).

Associations between change in symptoms/unmet needs over 12 months and HrQOL as measured by change in FACT-G over 12 months

| Change variable (12-month enrollment) . | n . | Change estimate∗ . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPI total | 119 | −1.42 | −2.14 to −0.70 | .0002 |

| Change to clinically relevant pain | 126 | −6.70 | −12.80 to −0.61 | .03 |

| BFI total | 118 | −1.69 | −2.36 to −1.02 | <.0001 |

| Change to clinically relevant fatigue | 126 | −5.55 | −12.13 to 1.03 | .10 |

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 118 | −1.92 | −2.82 to −1.03 | <.0001 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 118 | −1.84 | −2.75 to −0.94 | .0001 |

| Sustained unmet health care service needs | 126 | 2.35 | −2.87 to 7.57 | .37 |

| Sustained unmet psychological/emotional needs | 126 | 2.66 | −1.46 to 6.77 | .20 |

| Sustained unmet physical and daily health needs | 126 | 1.34 | −2.64 to 5.33 | .51 |

| Sustained unmet care and support needs | 126 | 2.46 | −4.75 to 9.67 | .50 |

| Sustained unmet sexual needs | 126 | 3.95 | −2.43 to 10.33 | .22 |

| Change to met health care service needs | 126 | 5.31 | 0.16-10.47 | .04 |

| Change to met psychological/emotional needs | 126 | 5.76 | 0.81-10.71 | .02 |

| Change to met physical and daily health needs | 126 | 7.20 | 1.90-12.50 | .008 |

| Change to met care and support needs | 126 | 6.32 | 1.10-11.55 | .02 |

| Change to met sexual needs | 126 | −0.33 | −6.19 to 5.54 | .91 |

| Increasing no. of unmet needs | 125 | −0.79 | −1.07 to −0.51 | <.0001 |

| Change variable (12-month enrollment) . | n . | Change estimate∗ . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPI total | 119 | −1.42 | −2.14 to −0.70 | .0002 |

| Change to clinically relevant pain | 126 | −6.70 | −12.80 to −0.61 | .03 |

| BFI total | 118 | −1.69 | −2.36 to −1.02 | <.0001 |

| Change to clinically relevant fatigue | 126 | −5.55 | −12.13 to 1.03 | .10 |

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 118 | −1.92 | −2.82 to −1.03 | <.0001 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | 118 | −1.84 | −2.75 to −0.94 | .0001 |

| Sustained unmet health care service needs | 126 | 2.35 | −2.87 to 7.57 | .37 |

| Sustained unmet psychological/emotional needs | 126 | 2.66 | −1.46 to 6.77 | .20 |

| Sustained unmet physical and daily health needs | 126 | 1.34 | −2.64 to 5.33 | .51 |

| Sustained unmet care and support needs | 126 | 2.46 | −4.75 to 9.67 | .50 |

| Sustained unmet sexual needs | 126 | 3.95 | −2.43 to 10.33 | .22 |

| Change to met health care service needs | 126 | 5.31 | 0.16-10.47 | .04 |

| Change to met psychological/emotional needs | 126 | 5.76 | 0.81-10.71 | .02 |

| Change to met physical and daily health needs | 126 | 7.20 | 1.90-12.50 | .008 |

| Change to met care and support needs | 126 | 6.32 | 1.10-11.55 | .02 |

| Change to met sexual needs | 126 | −0.33 | −6.19 to 5.54 | .91 |

| Increasing no. of unmet needs | 125 | −0.79 | −1.07 to −0.51 | <.0001 |

Change estimate interpretation: a 1-unit increase in the change in symptom variable over time (12-months minus enrollment) is associated with this change estimate in HrQOL on average as measured by total FACT-G score over time (12-months minus enrollment). For example, a patient who has a total BPI score increase from 5 points at enrollment to 6 points at 12-months will have, on average, a decreased total FACT-G score of 1.42 points (correlating with decreased HrQOL) over the same time period. Another example: a patient who has unmet health care service needs at enrollment but met health care service needs at 12 months will have, on average, an increased total FACT-G score of 5.31 points (correlating with increased HrQOL) over the same time period.

Discussion

In this prospective registry-based study of patients with ECD, we examined the longitudinal trajectory of patient-reported symptoms, unmet needs, and their association with HrQOL. Our findings demonstrate a high burden of symptomatology and unmet needs, as well as diminished HrQOL, in patients living with ECD. We identified significant associations at both PRO completion time points, at which greater severity of ECD symptoms, pain, fatigue, and burden of unmet needs were associated with lower HrQOL. We further demonstrated that a decrease in any symptom or the number of unmet needs was associated with improvement in HrQOL, whereas increase in any symptom or number of unmet needs was associated with a decrease in HrQOL.

It is important to emphasize the overall and consistently poor HrQOL reported by our ECD cohort, even within the broader context of cancer. A study of women surviving advanced-stage ovarian cancer found mean FACT-G scores of >80 for those with multiple recurrences, and close to 90 for those without.46 These scores are significantly higher than the mean total scores of 70 to 75 in patients with ECD reported here. One study of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma reported mean total FACT-G scores of 83 in this clinical population,47 and in a study of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia aged >60 years undergoing stem cell transplantation, median FACT-G was 80.48 These comparisons suggest that HrQOL in our patients is diminished even in comparison with those observed in other solid and hematologic cancers. There are likely many reasons for diminished HrQOL in ECD, however, our data suggest that the substantial symptom burden and unmet needs may play a key role in explaining this finding.

We have previously demonstrated the substantial burden of fatigue and pain27 as well as disease-related symptoms in ECD28 with a notably high prevalence of neurologic symptoms. Given the recurrent observation of diagnostic delay in ECD,20 and the observation in other cancers that symptom burden is greater in patients with more advanced disease at diagnosis,49 it stands to reason that symptom burden in ECD is substantial. The association between severity of both fatigue50 and pain51,52 and diminished HrQOL has been well-documented in a variety of cancers. An overall association between frailty in older patients with cancer and reduced HrQOL has been demonstrated in meta-analysis,53 which resonates with ECD and its older demographic and frequent physical impairments. Our observation that improvement in symptomatology is associated with improvement in HrQOL highlights the urgent need to identify and address these symptoms in patients with ECD in efforts to improve HrQOL.

Assessment of unmet supportive care needs has not been evaluated in ECD to date, and our data suggest an immense burden of unmet needs in our patients. Half of our cohort (50%) endorsed ≥5 unmet needs, and 30% endorsed ≥10 unmet needs. Most (58%) patients in our cohort endorsed moderately or highly unmet psychological or emotional needs in their baseline assessment, compared with 43% in a cohort of patients with head and neck cancer,54 26% in a cohort of patients with colorectal cancer,55 and 30% in a cohort of patients with mixed hematologic cancer.56 More than half (57%) of our patients endorsed moderately or highly unmet physical or daily health needs, compared with 21%, 35%, and 30% in the aforementioned cohorts, respectively. Last, 25% of our cohort endorsed unmet sexual needs, compared with 9%, 0%, and 8% in the aforementioned cohorts. We propose that there are likely multiple reasons for the high prevalence of unmet needs across domains, including the clinical heterogeneity of ECD with frequent multisystem involvement and disease rarity leading to delayed diagnosis and dearth of social support. Furthermore, the scarcity of information and expert care for ECD likely leads to unmet informational and educational needs. One systematic review corroborates the finding of frequent unmet needs in the setting of rare diseases.57 Unmet sexual needs may be related to frequent endocrine58 and neuroendocrine59 deficiencies in ECD, among other physical and neurologic impairments. The association between unmet needs and diminished QOL has been observed in a variety of more common cancers, including lung cancer,60 breast cancer,61 multiple myeloma, and B-cell lymphoma.62 Our finding that reduction of unmet needs in patients with ECD over time is associated with improvement in HrQOL identifies opportunities for improved care by screening for unmet needs and designing interventions to optimize disease education and psychosocial support. Virtual-type interventions may be ideal in this context of patients with a rare disease who are geographically dispersed.

The primary limitation of this study stems from the heterogeneity of our patients in terms of their treatment status and their position within their disease trajectory. We were unable to collect and analyze PROs at uniform time points such as before treatment or after a defined period of treatment. Similarly, we do not have longitudinal PRO data for patients undergoing identical or similar treatments. As a result, our cross-sectional data reflect a range of disease states and treatment statuses. Despite this variability, the associations we identified, particularly regarding severity of pain and fatigue and the burden of unmet needs, appear consistent despite this heterogeneity, suggesting these factors impose reduced HrQOL throughout the disease spectrum. Furthermore, our longitudinal analysis indicates that addressing these symptoms and unmet needs, regardless of the point in the disease trajectory, can lead to improvements in HrQOL, even after adjusting for variables such as age at ECD diagnosis, duration of illness, and presence of brain/parenchymal disease. These findings underscore the importance of clinicians identifying and mitigating these symptoms for all patients with ECD, regardless of their treatment status or disease chronicity. Larger prospective cohort-based studies evaluating more homogeneous patient subgroups would provide further clarity and strengthen these observations. In addition, we acknowledge that the association between severity of symptomatology and diminished QOL may be expected as it has been observed in other cancer cohorts repeatedly. We would assert, however, that the observation that modest improvements in symptoms over time can be associated with improvement in HrQOL, especially given the severity and chronicity of these symptoms, is not a foregone conclusion. On the contrary, it motivates efforts to avoid a nihilistic mentality toward dense and complex symptoms in favor of investigating and implementing interventions for the betterment of these patients’ experience.

Our study provides, to our knowledge, the first examination of HrQOL and longitudinal assessment of PROs in ECD, demonstrating a substantial burden of symptomatology associated with diminution of life enjoyment in these patients. The facts of ECD rarity and chronicity themselves contribute to, and amplify, these clinical and psychosocial features that are associated with diminished HrQOL. Mitigation of disease symptoms and addressing unmet supportive care needs emerge as pressing and achievable goals for improving care for patients with ECD. Future interventions designed to specifically target these areas will hopefully lead to progress in these important challenges.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (P30 CA008748, R37CA259260 [E.L.D. and K.S.P.], and T32CA275764 [P.H.M.]) and Population Sciences Research Program award (E.L.D. and K.S.P.). Additional support was received from the Frame Family Fund (E.L.D.), the Joy Family West Foundation (E.L.D.), the Applebaum Foundation (E.L.D.), and the Erdheim-Chester Disease Global Alliance (E.L.D.).

Authorship

Contribution: P.H.M. was responsible for conceptualization, interpretation, and drafting; A.S.R. was responsible for formal statistical analysis, interpretation, and drafting; D.B. and A.M.S. performed data collection and interpretation; D.F., K.B., G.G., T.M.A., and J.J.M. were responsible for conceptualization, interpretation, and drafting; K.S.P. was responsible for conceptualization, interpretation, drafting, and supervision; E.L.D. was responsible for conceptualization, data collection, interpretation, drafting, and supervision; and all authors reviewed and edited the final version of the manuscript and agreed with the submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: E.L.D. discloses unpaid editorial support from Pfizer Inc, and serves on an advisory board for Opna Bio, both outside the submitted work. G.G. reports consulting fee from Recordati; reports royalties from UpToDate; reports fees for advisory boards for Opna Bio, Seagen, and Sobi; and serves on an advisory board for SpringWorks Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Eli L. Diamond, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Second Floor Neurology, 160 East 53rd St, New York, NY 10022; email: diamone1@mskcc.org.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Eli L. Diamond (diamone1@mskcc.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.