Key Points

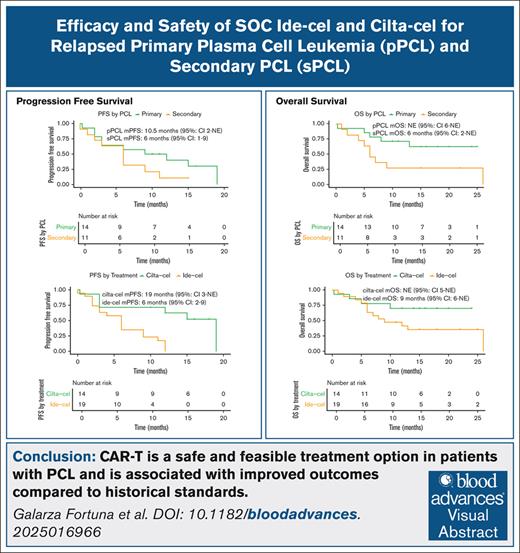

CAR-T is an effective and safe treatment option in patients with PCL.

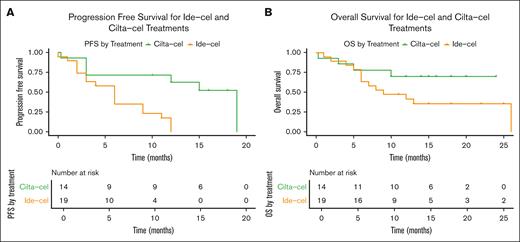

Despite similar objective responses with ide-cel and cilta-cel, patients with PCL derived greater benefit from cilta-cel than from ide-cel.

Visual Abstract

Despite significant therapeutic advances in multiple myeloma (MM), outcomes in patients with plasma cell leukemia (PCL) remain dismal. We conducted a multicenter retrospective analysis of patients with PCL who were treated with the B-cell maturation antigen–directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) products idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel). We identified 34 patients; 19 patients received ide-cel and 15 received cilta-cel. With a median follow-up of 11.9 months, the overall median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 9.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4-15) and the median overall survival (mOS) was 13.0 months (95% CI, 8 to not estimable [NE]). The 1-year cumulative incidence of progression or death was 72%, and the 1-year cumulative incidence of death was 47%. Patients who received cilta-cel had a longer mPFS (19.0 months vs 6.0 months) and mOS (>23 months [NE] vs 9.0 months) when compared with those treated with ide-cel. Similarly, the 1-year cumulative incidence of disease progression or death was 37.5% (95% CI, 17.4-68.5) with cilta-cel, whereas all patients treated with ide-cel progressed or died within 12 months of infusion. The rates of hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities were similar between patients treated with cilta-cel and those treated with ide-cel and were consistent with those reported in patients with MM. In this first multicenter study that evaluated patients with PCL who were treated with standard-of-care CAR-T products, we show that CAR-T is safe, feasible, and associated with improved outcomes when compared with historic standards.

Introduction

The treatment landscape of multiple myeloma (MM) has evolved rapidly over the last 20 years.1 Recently, B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–directed immunotherapeutics, including antibody-drug conjugates, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, and T-cell–redirecting bispecific antibodies, have transformed the treatment of relapsed and refractory MM (RRMM).2

Plasma cell leukemia (PCL), defined by the presence of ≥5% circulating plasma cells (PCs) in the peripheral blood, is considered primary PCL (pPCL) if identified in patients without a previous MM diagnosis and as secondary PCL (sPCL) when it arises as a leukemic transformation in patients with RRMM. PCL represents ∼0.5% to 4% of all MM cases3 and is characterized by an aggressive disease course and significantly inferior outcomes.4-7

Despite the use of effective MM-directed therapies, the outcomes in PCL remain poor. The median overall survival (mOS) is ∼13 months for pPCL and 3.5 months for sPCL with an overall 5-year survival of 11%.8 Furthermore, guidance on the therapeutic strategies for RR pPCL is limited to a few case reports, thus adding to the complexity of treating this condition.9-11

Two BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapies, namely idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel), have been approved for RRMM treatment and have led to significantly improved outcomes when compared with priorstandard-of-care (SOC) regimens. However, pivotal trials like KarMMa and CARTITUDE-1 excluded patients with PCL, and thus data on CAR T-cell outcomes for PCL cases are limited.12,13 This project aimed to describe the outcomes of patients with relapsed pPCL and sPCL after SOC CAR T-cell treatment.

Methods

Population and data collection

We conducted a retrospective, multicenter, observational study of patients who underwent leukapheresis before SOC ide-cel or cilta-cel treatment for PCL in 11 medical centers in the United States. Each center obtained independent institutional review board approval and informed consent per institutional requirements. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. PCL was defined as the presence of ≥5% circulating PCs in the peripheral blood, determined by either a peripheral smear or flow cytometry analysis. Patients who had ≥5% circulating PC at the time of the initial diagnosis were classified as having pPCL, whereas patients with ≥5% circulating PC at any time other than at initial diagnosis were classified as having sPCL.14 Our analysis was limited by the lack of available information on the presence of circulating PC at the time of CAR T-cell infusion. No central verification was performed.

Patients

All patients with a diagnosis of PCL at any time across their disease continuum who underwent leukapheresis from 1 April 2021 to 31 December 2022 for ide-cel or cilta-cel were reviewed. Only patients who received an ide-cel or a cilta-cel infusion were included in the final analysis.

Treatment and clinical assessment

Patients received bridging therapy at the discretion of the treating physician. All patients received standard lymphodepleting chemotherapy per institutional protocols.

Hematologic toxicity was graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0,15 whereas cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell (IEC)–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), and IEC-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis–like syndrome (IEC-HS) were assessed according to the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Criteria.16 Treatment of CRS, ICANS, and IEC-HS was per institutional guidelines, as were infectious disease prophylaxis. Response was assessed based on the International Myeloma Working Group Criteria.17 High-risk cytogenetics were defined by the presence of del17p, t(4;14), t(14;16), or alterations within chromosome 1q at any time point before CAR T-cell infusion. Patients with 2 documented high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities were classified as double hit, whereas those with 3 documented high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities were classified as triple hit.

Statistical analyses

Patients’ baseline characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics with medians, interquartile range, range, and percentages reported. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the time to events (OS and progression-free survival [PFS]); PFS was defined as the time from infusion to progression or death, whereas OS was defined as the time from leukapheresis or infusion to death. The baseline characteristics and adverse events were summarized separately according to the complete original data. For the primary analysis, missing values in the baseline covariates were handled using single imputation through a fully conditional specification method.18 We applied matching weights19 to account for baseline confounding by mitigating the imbalance between baseline covariates while downweighing patients who had extremely high or low probabilities of being in 1 treatment or exposure group. Specifically, we first estimated the propensity scores (PSs) as the probability of being exposed to sPCL and being assigned to cilta-cel, separately (supplemental Figure 1). Then, we calculated the matching weights at the patient level using the estimated PSs. Finally, we fitted a weighted Cox regression to estimate the overall treatment effects as hazard ratios (HRs). We included the treatment or exposure as the only independent variable in the model because potential baseline confounders (age >65 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] score of ≥2, pPCL, previous lines of therapy, presence of high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, presence of extramedullary disease before apheresis, and presence of ≥50% PCs in the bone marrow, and Revised International Staging System stage III) were controlled through weighting (supplemental Figure 2). To assess the impact of data imputation, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which an unknown category was created for missing values in the baseline covariates (supplemental Figure 3). This allowed us to retain patients with missing data in our study cohort and prevent the loss of statistical power. The missing data were summarized in supplemental Table 1A-B. In addition, we applied overlap weights20 in our sensitivity analysis to prevent unstable effects estimated using matching weights. Lastly, we identified 19 patients with no missing data for any of the variables included in the matching model and performed a complete case analysis to assess PFS and OS in this subgroup of patients, which can be found in supplemental Tables 2-4. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 30.0.0.21 and R version 4.4.2.22

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 43 patients with a known history of PCL who underwent leukapheresis before CAR T-cell therapy, including 24 (56%) and 19 (44%) patients designated to receive ide-cel and cilta-cel, respectively, were identified. Active PCL at the time of CAR T-cell therapy was not required. Patients with a history of pPCL at the time of diagnosis were classified as having relapsed pPCL, whereas patients with PCL documented at any other time were classified as having sPCL. A total of 9 patients (21%) underwent leukapheresis but did not receive a CAR T-cell infusion.

Our analysis focused on the 34 patients who underwent CAR T-cell infusion with 19 (56%) of those receiving ide-cel and 15 (44%) receiving cilta-cel. Overall, 9 patients (27%) did not have available PCL subtype information, 14 patients (41%) had documented relapsed pPCL, and 11 patients (32%) had sPCL. In the ide-cel cohort, 7 patients (37%) were classified as relapsed pPCL, whereas 10 patients (53%) had documented sPCL. Similarly, in the cilta-cel cohort, 7 patients (47%) had documented relapsed pPCL, and 1 patient (7%) had documented sPCL.

Overall, the mean age was 59 years (range, 30-76), 22 patients (65%) were male, 5 patients (15%) had Revised International Staging System stage III disease, and 26 (76%) had any high-risk cytogenetic abnormality. The most common high-risk fluorescence in situ hybridization cytogenetic abnormalities were gain or amplification (amp) of chromosome 1q, which was evident in 16 (47%) patients, and del17p, seen in 12 (35%) patients. Nine patients (26%) had double-hit disease, whereas 1 patient (3%) had triple-hit PCL. The median number of previous lines of therapy was 5 (interquartile range, 4-6; range, 3-11). Patients with relapsed pPCL had a median of 4.5 (range, 4-7) previous lines of therapy, whereas those with sPCL had a median of 6 (range, 3-10) previous lines of therapy. The baseline characteristics for all patients included in the study can be found in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for patients with PCL treated with ide-cel and cilta-cel

| Parameter . | Overall (N = 34) . | Ide-cel (n = 19) . | Cilta-cel (n = 15) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), y | 59 (30-76) | 61 (44-76) | 55 (30-70) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 22 (65) | 12 (63) | 10 (67) |

| Female | 12 (35) | 7 (37) | 5 (33) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 30 (88) | 17 (89) | 13 (87) |

| Black | 3 (9) | 1 (5) | 2 (13) |

| Other | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| ECOG, n (%) | |||

| ECOG score of 0-1 | 30 (88) | 18 (95) | 12 (80) |

| ECOG score of ≥2 | 3 (9) | 1 (5) | 2 (13) |

| ECOG unknown | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| PCL subtype, n (%) | |||

| Relapsed pPCL | 14 (41) | 7 (37) | 7 (47) |

| sPCL | 11 (32) | 10 (53) | 1 (7) |

| Unknown PCL subtype | 9 (27) | 2 (11) | 7 (47) |

| R-ISS, n (%) | |||

| R-ISS stage I | 4 (12) | 1 (5) | 3 (20) |

| R-ISS stage II | 18 (53) | 13 (68) | 5 (33) |

| R-ISS stage III | 5 (15) | 2 (11) | 3 (20) |

| R-ISS stage unknown | 7 (20) | 3 (16) | 4 (27) |

| High-risk cytogenetics, n (%) | 26 (76) | 18 (95) | 8 (53) |

| High-risk cytogenetics unknown, n (%) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) |

| Deletion 17p | 12 (35) | 8 (42) | 4 (27) |

| t (4;14) | 4 (12) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) |

| t (4;14) unknown | 2 (6) | 1 (5) | 1 (7) |

| t (14;16) | 4 (12) | 2 (11) | 2 (13) |

| t (14;16) unknown | 3 (9) | 1 (5) | 2 (13) |

| 1q gain/amp | 16 (47) | 11 (58) | 5 (33) |

| 1q gain/amp unknown | 4 (12) | 2 (11) | 2 (13) |

| Double hit | 9 (26) | 6 (32) | 3 (20) |

| Triple hit | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Extramedullary disease, n (%) | 10 (29) | 6 (32) | 4 (27) |

| Previous auto-HSCT, n (%) | 31 (91) | 18 (95) | 13 (87) |

| TCR, n (%) | 25 (74) | 15 (79) | 10 (67) |

| TCR unknown, n (%) | 5 (15) | 4 (21) | 1 (7) |

| PDR, n (%) | 11 (32) | 7 (37) | 4 (27) |

| PDR unknown, n (%) | 5 (15) | 4 (21) | 1 (7) |

| Previous lines of therapy, median (IQR) | 5 (4-6) | 6 (5-7) | 5 (4-5) |

| Ferritin before LD, median (IQR), μg/L | 416 (175-1682) | 470 (230-1569) | 416 (168-1482) |

| Ferritin before LD unknown, n (%) | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| CRP, median (IQR), mg/L | 2.8 (0.4-5.6) | 2.4 (0.4-4.9) | 2.9 (0.6-6.6) |

| CRP unknown, n (%) | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| BMPC ≥50%, n (%) | 11 (32) | 9 (47) | 2 (13) |

| BMPC ≥50% unknown, n (%) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 3 (20) |

| Parameter . | Overall (N = 34) . | Ide-cel (n = 19) . | Cilta-cel (n = 15) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), y | 59 (30-76) | 61 (44-76) | 55 (30-70) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 22 (65) | 12 (63) | 10 (67) |

| Female | 12 (35) | 7 (37) | 5 (33) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 30 (88) | 17 (89) | 13 (87) |

| Black | 3 (9) | 1 (5) | 2 (13) |

| Other | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| ECOG, n (%) | |||

| ECOG score of 0-1 | 30 (88) | 18 (95) | 12 (80) |

| ECOG score of ≥2 | 3 (9) | 1 (5) | 2 (13) |

| ECOG unknown | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| PCL subtype, n (%) | |||

| Relapsed pPCL | 14 (41) | 7 (37) | 7 (47) |

| sPCL | 11 (32) | 10 (53) | 1 (7) |

| Unknown PCL subtype | 9 (27) | 2 (11) | 7 (47) |

| R-ISS, n (%) | |||

| R-ISS stage I | 4 (12) | 1 (5) | 3 (20) |

| R-ISS stage II | 18 (53) | 13 (68) | 5 (33) |

| R-ISS stage III | 5 (15) | 2 (11) | 3 (20) |

| R-ISS stage unknown | 7 (20) | 3 (16) | 4 (27) |

| High-risk cytogenetics, n (%) | 26 (76) | 18 (95) | 8 (53) |

| High-risk cytogenetics unknown, n (%) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) |

| Deletion 17p | 12 (35) | 8 (42) | 4 (27) |

| t (4;14) | 4 (12) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) |

| t (4;14) unknown | 2 (6) | 1 (5) | 1 (7) |

| t (14;16) | 4 (12) | 2 (11) | 2 (13) |

| t (14;16) unknown | 3 (9) | 1 (5) | 2 (13) |

| 1q gain/amp | 16 (47) | 11 (58) | 5 (33) |

| 1q gain/amp unknown | 4 (12) | 2 (11) | 2 (13) |

| Double hit | 9 (26) | 6 (32) | 3 (20) |

| Triple hit | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Extramedullary disease, n (%) | 10 (29) | 6 (32) | 4 (27) |

| Previous auto-HSCT, n (%) | 31 (91) | 18 (95) | 13 (87) |

| TCR, n (%) | 25 (74) | 15 (79) | 10 (67) |

| TCR unknown, n (%) | 5 (15) | 4 (21) | 1 (7) |

| PDR, n (%) | 11 (32) | 7 (37) | 4 (27) |

| PDR unknown, n (%) | 5 (15) | 4 (21) | 1 (7) |

| Previous lines of therapy, median (IQR) | 5 (4-6) | 6 (5-7) | 5 (4-5) |

| Ferritin before LD, median (IQR), μg/L | 416 (175-1682) | 470 (230-1569) | 416 (168-1482) |

| Ferritin before LD unknown, n (%) | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| CRP, median (IQR), mg/L | 2.8 (0.4-5.6) | 2.4 (0.4-4.9) | 2.9 (0.6-6.6) |

| CRP unknown, n (%) | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| BMPC ≥50%, n (%) | 11 (32) | 9 (47) | 2 (13) |

| BMPC ≥50% unknown, n (%) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 3 (20) |

High-risk cytogenetics include del17P, t(4;14), t(14;16). The following parameters had missing data points (percentage of available information reflected): ECOG (97%), PCL subtype (74%), R-ISS stage (79%), t(4;14) (94%), t(14;16) (92%), 1q gain/amp (85%), ferritin prior LD (97%), CRP prior LD (97%), and BMPC (88%).

BMPC, bone marrow plasma cell; CRP, C-reactive protein; IQR, interquartile range; LD, lymphodepleting chemotherapy; PDR, pentadrug refractory; R-ISS, Revised International Staging System; TCR, triple-class refractory.

Efficacy

Response rates

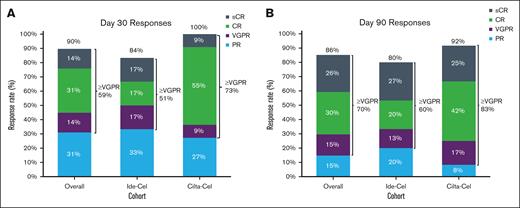

The overall response rate (ORR) at day 30 in patients with evaluable disease was 90% and was similar between those treated with ide-cel and those treated with cilta-cel at 84% vs 100%, respectively. In total, 59% of patients achieved a very good partial response (VGPR) or better, including 51% and 73% of patients treated with ide-cel and cilta-cel, respectively (Figure 1A). The ORR at day 90 was 86% with an ORR of 80% among patients who received ide-cel and 92% among those who received cilta-cel; 70% of patients achieved a VGPR or better (Figure 1B).

Best overall response rate for the overall population and for each CAR T-cell therapy product. Day 30 (A) and day 90 (B) response in the ide-cel, cilta-cel, and overall population. CR, complete response; PR, partial response; sCR, stringent complete response.

Best overall response rate for the overall population and for each CAR T-cell therapy product. Day 30 (A) and day 90 (B) response in the ide-cel, cilta-cel, and overall population. CR, complete response; PR, partial response; sCR, stringent complete response.

Three patients in the entire cohort had previous BCMA-directed treatment before proceeding with SOC CAR T-cell therapy; 1 patient was treated with SOC ide-cel and 2 patients were treated SOC cilta-cel. All 3 patients responded to SOC BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, including 1 patient who was treated with ide-cel and who achieved a VGPR and 2 patients who were treated with cilta-cel, including 1 complete response and 1 stringent complete response.

PFS

The median overall follow-up time from infusion was 11.9 months (range, 0.3-27); 8.6 months (range, 1.4-27) and 13.8 months (range, 0.3-13.8) for those treated with ide-cel and cilta-cel, respectively. The median time from diagnosis to CAR T-cell therapy was 42 months (range, 19-191) for patients treated with ide-cel and 33 months (range, 8-92) for patients treated with cilta-cel. Furthermore, the median time from diagnosis to CAR T-cell infusion in patients with relapsed pPCL was 36 months (range, 26-54) for ide-cel and 24 months (range, 8-92) for cilta-cel (Table 2). Patients with documented sPCL received ide-cel at a median of 53.5 months (range, 19-191) after the initial diagnosis. Only 1 patient with documented sPCL received cilta-cel 47 months after the initial diagnosis.

Treatment timeline and outcomes of patients with relapsed pPCL

| Treatment . | Median time from diagnosis (range), mo . | Median lines of therapy (range) . | mPFS (95% CI), mo . | mOS (95% CI), mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cilta-cel | 24 (8-92) | 4 (4-6) | 19 (3 to NE) | NE (5 to NE) |

| Ide-cel | 36 (26-54) | 6 (4-7) | 6 (2 to NE) | NE (8 to NE) |

| Treatment . | Median time from diagnosis (range), mo . | Median lines of therapy (range) . | mPFS (95% CI), mo . | mOS (95% CI), mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cilta-cel | 24 (8-92) | 4 (4-6) | 19 (3 to NE) | NE (5 to NE) |

| Ide-cel | 36 (26-54) | 6 (4-7) | 6 (2 to NE) | NE (8 to NE) |

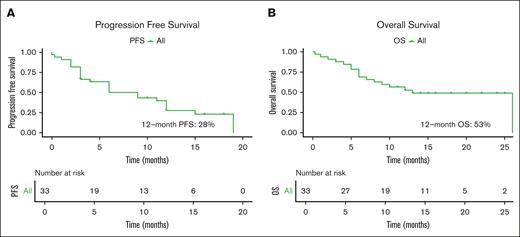

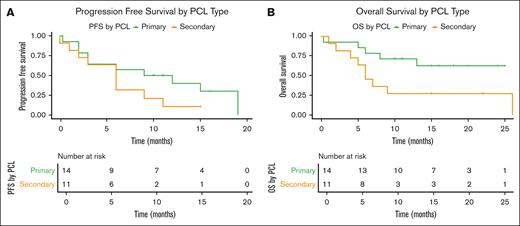

The overall mPFS was 9 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4-15) and the 12-month cumulative incidence of progression or death rate was 72% (95% CI, 49.4-84.6; Figure 2A; supplemental Table 5). The mPFS for patients with relapsed pPCL was 10.5 months (95% CI, 2 to not estimable [NE]) and 6 months (95% CI, 1-9) for those with sPCL (Figure 3A; supplemental Table 6). By 12 months, the cumulative incidence of disease progression or death was 60% (95% CI, 35.3-85.5) for patients with relapsed pPCL and 89.4% (95% CI, 62.7-99.54) for patients with sPCL (supplemental Table 5).

Overall progression free and overall survival. PFS (A) and OS (B) in patients.

Progression free and overall survival in patients with pPCL compared to sPCL. PFS (A) and OS (B) in patients with pPCL and sPCL.

Progression free and overall survival in patients with pPCL compared to sPCL. PFS (A) and OS (B) in patients with pPCL and sPCL.

The mPFS for patients treated with ide-cel was 6 months (95% CI, 2-9) vs 19 months (95% CI, 3 to NE) in patients treated with cilta-cel (Figure 4A). By 12 months, the cumulative incidence of disease progression or death was 37.5% (95% CI, 17.4-68.5) for patients treated with cilta-cel, while all uncensored patients treated with ide-cel progressed or died within a year of receiving therapy (supplement Table 5). The mPFS of patients with relapsed pPCL treated with ide-cel was 6 months (95% CI, 2 to NE), and 19 months (95% CI, 3 to NE) for those treated with cilta-cel.

Progression free survival and overall survival in patients treated with ide-cel versus cilta-cel. PFS (A) and OS (B) in patients treated with ide-cel and cilta-cel.

Progression free survival and overall survival in patients treated with ide-cel versus cilta-cel. PFS (A) and OS (B) in patients treated with ide-cel and cilta-cel.

Three patients in the study had previous exposure to a BCMA-targeting therapy. Of these, 2 patients developed disease progression or death during the study follow-up; 1 patient who received ide-cel progressed 3 months after infusion, whereas the other patient who received cilta-cel had evidence of disease progression 19 months after infusion. One patient who was treated with cilta-cel was censored 15 months after infusion.

Our univariate analysis showed that patients who were treated with cilta-cel had a 0.21-fold risk (95% CI, 0.07-0.61) of progression or death when compared with patients treated with ide-cel. Patients with sPCL had a 1.86-fold risk (95% CI, 0.73-4.78) of progression or death when compared with patients with relapsed pPCL. Similarly, patients with 1q amp or gain had a 3.36-fold risk (95% CI, 1.2-9.1) of progression or death when compared with patients without this cytogenetic abnormality (supplemental Table 7; supplemental Figure 4A). Information regarding the presence of t(11;14) was available for 80% of patients, and based on this patient sample, the mPFS did not differ in patients with and those without t(11;14) (results not shown).

In the multivariate analysis, using a single imputation for missing values in the baseline covariates and matching weights to control for confounding, patients with sPCL had a 1.3-fold risk (95% CI, 0.43-4.00) for progression or death when compared with patients with relapsed pPCL. Patients treated with cilta-cel had a 0.34-fold risk (95% CI, 0.11-1.08) for progression or death when compared with those treated with ide-cel. In the sensitivity analysis in which an unknown category was created for missing values and overlap weights were used to control for confounding, patients with sPCL had a 0.91-fold risk (95% CI, 0.31-2.68) of disease progression or death when compared with patients with pPCL (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis of PFS and OS with CAR T-cell therapy

| . | HR (95% CI) . | |

|---|---|---|

| PFS . | OS . | |

| Primary analysis | ||

| Treatment (cilta-cel vs ide-cel) | 0.34 (0.11-1.08) | 0.54 (0.14-2.05) |

| PCL (sPCL vs pPCL) | 1.31 (0.43-4.00) | 2.19 (0.48-9.98) |

| Sensitivity analysis, PCL (sPCL vs pPCL) | 0.91 (0.31-2.68) | 2.27 (0.45-11.46) |

| . | HR (95% CI) . | |

|---|---|---|

| PFS . | OS . | |

| Primary analysis | ||

| Treatment (cilta-cel vs ide-cel) | 0.34 (0.11-1.08) | 0.54 (0.14-2.05) |

| PCL (sPCL vs pPCL) | 1.31 (0.43-4.00) | 2.19 (0.48-9.98) |

| Sensitivity analysis, PCL (sPCL vs pPCL) | 0.91 (0.31-2.68) | 2.27 (0.45-11.46) |

The primary analysis used a single imputation to address missing values in the covariates and applied a method of matching weights. For the sensitivity analysis, we created an additional category to account for the missing covariate values and used the overlap weights. The primary analysis had a sample size of 34 for primary treatment (cilta-cel vs ide-cel). The primary and the sensitivity analyses had a sample size of 25 for PCL treatment (sPCL vs pPCL).

OS

In the intention to treat cohort, including 43 patients who underwent leukapheresis, the mOS from leukapheresis to death was 12 months (95% CI, 8 to NE). In the as-treated cohort, the mOS from leukapheresis to death was 26 months (95% CI, 12 to NE). In addition, the mOS from infusion to death in our as-treated cohort of 34 patients who underwent CAR T-cell therapy was 13 months (95% CI, 8 to NE), and the 12-month cumulative incidence of death was 47.0% (95% CI, 26.4-61.9; Figure 2B). Among those with relapsed pPCL, the mOS was NE (95% CI, 6 to NE), whereas it was 6 months (95% CI, 2 to NE) among patients with sPCL (Figure 3B; supplemental Table 6). The 12-month cumulative incidence of death for patients with relapsed pPCL and sPCL were 28.6% (95% CI, 11.8-59.4) and 72.7% (95% CI, 46.1-93.5), respectively (supplemental Table 5).

In patients treated with ide-cel, the mOS was 9 months (95% CI, 6 to NE) and was NE (95% CI, 5 to NE) for those treated with cilta-cel (Figure 4B; supplemental Table 6). By 12 months, the cumulative incidence of death for patients who received ide-cel was 58.6% (95% CI, 37.9-80.4) and 29.9% (95% CI, 12.4-61.5) for patients who received cilta-cel (supplemental Table 5). The mOS for patients with relapsed pPCL treated with either ide-cel or cilta-cel was NE.

In the cohort previously exposed to a BCMA-targeting agent before receiving ide-cel or cilta-cel, 1 patient who received ide-cel died during the study follow-up time at 4 months after infusion secondary to disease progression. The remaining 2 patients, both treated with cilta-cel, were still alive at 15 and 20 months after infusion.

Our univariate analysis showed that patients treated with cilta-cel had a 0.42-fold risk (95% CI, 0.13-1.29) of death when compared with patients treated with ide-cel. Patients with sPCL had a 2.89-fold risk (95% CI, 0.94-8.92) of death when compared with patients with relapsed pPCL. Similarly, patients with an ECOG score of ≥2 had a 6.89-fold risk (95% CI, 1.44-32.9) of death when compared with patients with an ECOG score of <2 at lymphodepletion (supplemental Table 8; supplemental Figure 3B). Furthermore, the mOS was similar in patients with and without t(11;14).

In the multivariate analysis, as previously described, patients with sPCL had a 2.19-fold risk (95% CI, 0.48-9.98) of death when compared with patients with relapsed pPCL. Patients treated with cilta-cel had a 0.54-fold risk (95% CI, 0.14-2.05) of death when compared with patients who received ide-cel. In the sensitivity analysis, patients with sPCL had a 2.27-fold risk (95% CI, 0.45-11.46) for death when compared with those with relapsed pPCL (Table 3).

Safety

In our cohort of 34 patients, 79% of patients (n = 27) developed any-grade CRS, whereas 6% (n = 2) had CRS grade ≥3. In the ide-cel cohort, 84% (n = 16) of patients developed any-grade CRS and only 5% (n = 1) of those developed grade ≥3 CRS. In the cilta-cel cohort, 73% of patients (n = 11) developed any-grade CRS and only 7% (n = 1) of those developed grade ≥3 CRS. Any-grade ICANS occurred in 15% (n = 5) of patients and all but 1 being grade 1. In the ide-cel cohort, the ICANS rate was 21% (n = 4), all of which were grade 1. One patient in the cilta-cel cohort developed grade 5 ICANS; no other ICANS was observed in this cohort (supplemental Table 9). One patient who received cilta-cel developed a delayed non-ICANS neurotoxicity 50 days after cilta-cel infusion. Although the diagnostic criteria for IEC-HS have not been accepted widely and are grossly based on expert consensus and the recognition of this entity is likely underestimated,23 only 1 patient developed IEC-HS, and this patient had received cilta-cel. Overall, 2 patients (6%) required escalation of care to the intensive care unit following infusion, and 1 of those received ide-cel and 1 received cilta-cel. The reasons for intensive care unit admission were grade 1 ICANS and grade 3 CRS in the 1 patient treated with ide-cel and grade 5 CRS for the patient treated with cilta-cel.

Overall, 47% (n = 16) of patients developed an infectious complication following CAR T-cell infusion. The most common infectious etiology was bacterial, documented in 8 patients (24%), whereas 7 (21%) patients developed a viral infection. Regarding hematologic adverse events, on day 90, 7 (21%) patients remained neutropenic, whereas 14 (41%) remained anemic and 13 (38%) remained thrombocytopenic (supplemental Table 9).

A total of 17 deaths occurred during the study follow-up, and the median time to death was 10.5 months (range, 0.3-26). The most common cause of death observed was directly related to disease progression (n = 14 [88%]). In the cilta-cel cohort, 1 patient died secondary to CRS complications and another secondary to ICANS complications. In the ide-cel cohort, 1 death was associated with the development of acute leukemia following ide-cel infusion. This patient developed acute myeloid leukemia 4.6 months after infusion when soft tissue was biopsied and delivered results consistent with myeloid sarcoma.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter study that reported the clinical outcomes of patients with PCL who received SOC BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy. We observed that BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy in patients with PCL was feasible and safe and that, at 30 and 90 days after CAR T-cell infusion, the ORRs were consistent with a previously reported MM clinical trial that excluded this patient population and real-world outcomes.

Immune effector therapies, such as CAR T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies, are shaping the therapeutic landscape for patients with RRMM. When compared with physician choice SOC, in patients with lenalidomide refractory MM after 1 to 3 previous lines of therapy, cilta-cel has a 30-month PFS rate of 59.4% vs 25.7% (HR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.22-0.39; P < .001) and a 30-month OS rate of 76.4% vs 63.8% (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.39-0.79; P = .0009).24 Similarly, the most recently reported mPFS with ide-cel in patients with triple-class exposed RRMM and 2 to 4 previous lines of therapy was 13.8 months (95% CI, 11.8-16.1) vs 4.4 months (95% CI, 3.4-5.8) with an HR of 0.49 (95% CI, 0.38-0.63) when compared with patients treated with SOC, whereas the mOS was 41.4 months (95% CI, 30.9 to NE) vs 37.9 months (95% CI, 23.4 to NR) with an HR of 1.01 (95% CI, 0.73-1.40).25 These important data highlight the impressive outcomes associated with CAR T-cell therapy in RRMM, however, as is the case with a vast majority of trials for patients with PC dyscrasias, patients with PCL were excluded from these registration trials and data on the safety and efficacy of BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy in patients with PCL remain scant.

The survival of patients with pPCL has improved dramatically with the incorporation of autologous stem cell transplant and novel therapeutic agents, however, it remains greatly inferior when compared with patients with MM.26 The mOS of patients diagnosed between 1973 to 1995 was 5 months as opposed to 12 months in those diagnosed between 2006 and 2009.27 Most recently, the 1-year OS in patients with pPCL was 76% (95% CI, 57-87).28 Similarly, patients with pPCL treated with novel therapeutic agents had an mOS of 29 months (95% CI, 19.6-38.3).29 Our data are consistent with these studies, showing an mOS of 13 months with better outcomes seen in patients with relapsed pPCL than in those with sPCL (1-year cumulative incidence of death of 28.6% for relapsed pPCL and 72.7% for sPC). This suggests that CAR T-cell therapy is an effective therapeutic and should be considered a treatment option for patients with relapsed pPCL even in those with heavily pretreated disease.

Unfortunately, outcomes in patients with sPCL remain dismal and significantly below that of patients with pPCL. The most recently described mPFS in patients with sPCL was 2.2 months, with an mOS of 3.1 months in a cohort of patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2024. These outcomes were significantly lower than the pPCL cohort reported in the same study, which had an mPFS of 38.3 and an mOS that was not reached during the allotted study follow-up.28 Our study showed an mPFS and mOS of 6 months in patients with sPCL who were treated with BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy and thus supports the use of CAR T-cell therapy in patients with sPCL. However, a significant difference in outcomes between pPCL and sPCL persists and was evident in our study, stressing the need for further therapeutic options and CAR T-cell optimization for this patient population. Importantly, our study outlines the need for clinical trials to assess the role of earlier use of CAR T-cell therapy and other novel immunotherapeutics in pPCL.

Although cilta-cel and ide-cel are associated with exceptional outcomes in MM when compared with previously introduced novel agents,12,13 multiple real-world studies have suggested improved outcomes with cilta-cel when compared with ide-cel in patients with RRMM.30,31 For instance, in a matched-adjusted indirect comparison, the mPFS with cilta-cel was 24.3 months as opposed to 12.5 months with ide-cel.31 This difference is consistent with our observed difference in the mPFS and mOS between cilta-cel and ide-cel, which demonstrated an mPFS of 19 months with cilta-cel vs 6 months with ide-cel. These results highlight the improved efficacy of cilta-cel over ide-cel in patients with PCL and propose cilta-cel as the preferred treatment option for patients with PCL. An important observation is that the current manufacturing time for both commercially approved CAR T-cell products for MM is approximately 4 weeks,32,33 and perhaps with this faster manufacturing time, the proportion of patients who undergo leukapheresis but do not receive CAR T-cell infusion because of early mortality could probably be lower than the 21% of patients reported here.

Various studies have reported that patients with PCL harbor higher frequency of cytogenetic abnormalities that are known to be associated with poor outcomes in MM when compared with their MM counterparts.8,34 In our cohort, 95% of patients treated with ide-cel and 40% treated with cilta-cel had any high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities. The most commonly observed high-risk cytogenetic abnormality was 1q gain/amp, which was present in 50% of patients. This is comparable with the recently reported frequency of 1q gain/amp by Shalaby et al.28 The presence of additional copies of chromosome 1q has been associated with poor outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed and RRMM despite the use of highly effective therapies.35,36 Patients with PCL have a higher prevalence of 1q gain/amp than those with MM,34 however, the association with poor outcomes in PCL is less clear. We observed a 3.36-fold risk of progression or death in patients with 1q gain/amp when compared with patients without this copy number alteration, whereas no other cytogenetic abnormality was associated with worse PFS or OS.

Regarding the safety of CAR T-cell therapy in patients with PCL, when compared with the pivotal KarMMa and CARTITUDE-1 trials, we observed similar rates of CRS and ICANS both between cohorts and when compared to the major trials. Similarly, the rates of hematologic toxicities were also similar between the 2 cohorts and comparable to the pivotal KarMMA and CARTITDE-1 trials, with only 1 patient in the entire cohort requiring a stem cell boost for chronic cytopenia.37,38

Infections are among the most commonly observed complications after BCMA-directed therapies.39 Infections were reported in 58% of patients in CARTITUDE-1 and 69% in KarMMA.37,38 In a recent single-center retrospective analysis, 85% of patients who received BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy developed an infection complication, with viral infections being the most common etiology of these events (40%).40 Our observed rate of infectious complications is comparable to these previously observed number, occurring in 47% of the analyzed patients.

Although informative, our study has some limitations, which include its retrospective design, short follow-up, and the inherited bias related to this study design, small sample size, and the response assessment that was documented by the investigator only with no independent review committee oversight. Our univariate analysis result is subject to low power given the small number of events and, as such, this analysis is vulnerable to baseline confounding and is only for exploring associations and not to determine causation. Lastly, data regarding the subtypes of PCL (pPCL vs sPCL) and percentage of circulating PCs at the time of lymphodepletion and/or CAR T-cell infusion were missing in many patients, making it difficult to assess how these characteristics affected the efficacy and safety of CAR T-cell therapy. Similarly, for our study, pPCL referred to patients with a history of pPCL and not active pPCL at the time of CAR T-cell therapy

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that CAR T-cell therapy is a safe and effective option for patients with PCL. Responses in this patient population were similar to those observed in the MM population. The long-term outcomes remain poor, and thus this remains an area of unmet need, highlighting the need for novel therapeutics for this high-risk disease.

Authorship

Contribution: G.M.G.F. and D.W.S. conceived the project, critically analyzed and interpreted the results, and wrote the first or subsequent drafts of the manuscript; E.N., G.M.G.F., and D.W.S. performed the data collection, statistical analyses, and interpretation; and all authors contributed substantially to data collection and/or manuscript revision and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.M. reports serving on advisory committees for Janssen and Sanofi. J.K. reports serving as a consultant for GPCR Therapeutics, Janssen, Prothena, Legend Biotech; and receiving research funding from Prothena, Ascentage, Janssen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, and GPCR Therapeutics. J.A.D. reports serving as a consultant for Janssen and Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS); and serving on a speaker bureau for Janssen. L.S. reports serving on a scientific advisory board for BMS, Janssen, and Novartis. J.M. reports serving as a consultant for Envision, Novartis, Caribou Biosciences, Sena Technologies, Legend Biotech, and Cargo Therapeutic; serving as a consultant and on the advisory board for Kite, SciMentum, AlloVir, BMS, CRISPR Therapeutics, and Nektar; and serving on the advisory board for Autolous. B.D. reports receiving research funding from C4 Therapeutics, Sanofi, CARsgen, Acrellx, and Janssen; receiving honoraria from BMS, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Pfizer, Janssen, and Genentech; and serving on the speaker bureau for Karyopharm Therapeutics and Pfizer. A.R. reports serving on advisory boards for BMS, Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), Caribou Biosciences, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Sanofi, and Adaptive; and receiving research support from JNJ, BMS, and Caribou Biosciences. R.S. reports receiving honoraria from Janssen, BMS, Genentech, Karyopharm Therapeutics, MJH Life Sciences, and OncLive; serving on a steering committee for BMS; receiving research support from Janssen, BMS, C4 Therapeutics, Gracell Therapeutics, and Heidelberg Pharma; and serving on advisory boards for Genentech, Janssen, BMS, and Karyopharm Therapeutics. A.A. reports research funding from AbbVie, Adaptive Biotech, K36 Therapeutics, Janssen, and Regeneron and an advisory role with Karyopharm, Bristol Myers Squibb, Sanofi, Janssen, and Pfizer. L.A.Jr. reports receiving research funding from BMS, AbbVie, Janssen, and Cellectar; serving as a consultant or in an advisory role for Celgene, Janssen, Amgen, BMS, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), AbbVie, BeiGene, Cellectar, Sanofi, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Prothena; and serving on the data safety and monitoring board for Prothena. A.B. reports receiving consulting fees from Kite/Gilead, Autolus, and Legend. W.C. reports serving on an advisory board for Poseida Therapeutics and serving as an invited speaker for Caribou Biosciences. H.H. reports serving on an advisory board for Janssen and serving on the speaker bureau for Janssen and Karyopharm Therapeutics. L.P. reports receiving research funding from BMS and Karyopharm Therapeutics. D.K.H. reports serving as a consultant for BMS, Janssen, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Karyopharm Therapeutics; and receiving research funding from BMS, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Adaptive Biotech, and Pentecost Myeloma Research Center. D.W.S. reports serving as a consultant for GSK, JNJ, Sanofi, AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer, Bioline, Arcellx, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Opna Bio, Regeneron, and Caribou Biosciences. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Douglas W. Sborov, Huntsman Cancer Institute at The University of Utah, 1950 Circle of Hope, Salt Lake City, UT 84112; email: douglas.sborov@hci.utah.edu.

References

Author notes

Deidentified data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Douglas W. Sborov (douglas.sborov@hci.utah.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.