Key Points

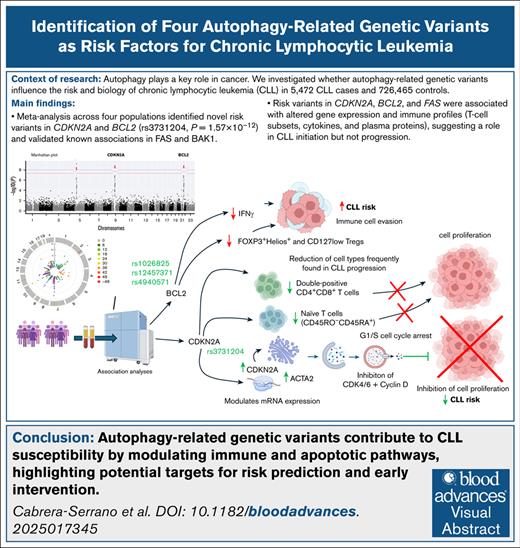

CDKN2A and BCL2 SNPs are newly linked to CLL risk, with CDKN2A rs3731204 showing the strongest association (P = 1.57 × 10−12).

These variants are linked to altered gene expression (eg, CDKN2A, ACTA2) and affect immune responses but not survival or treatment timing.

Visual Abstract

We investigated the influence of 55 583 autophagy-related single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) risk across 4 independent populations comprising 5472 CLL cases and 726 465 controls. We also examined their impact on overall survival (OS), time to first treatment (TTFT), autophagy flux, and immune responses. A meta-analysis of the 4 populations identified, to our knowledge, for the first time, significant associations between CDKN2A (rs3731204) and BCL2 (rs4940571, rs12457371, and rs1026825) SNPs and CLL risk, with CDKN2A showing the strongest association (P = 1.57 × 10−12). We also validated previously reported associations for FAS, BCL2, and BAK1 SNPs with CLL risk (P = 4.73 × 10−21 to 3.39 × 10−9). The CDKN2Ars3731204 and FASrs1926194 SNPs associated with increased CDKN2A and ACTA2 messenger RNA expression levels in the whole blood and/or lymphocytes (P = 5.1 × 10−7, P = 1.58 × 10−21, and P = 7.8 × 10−41), although no significant effect on autophagy flux was observed. However, associations were found between CDKN2A, BCL2, and FAS SNPs and various T-cell subsets, cytokine production, and circulating concentrations of interferon gamma, tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand, CD40, chemokine ligand 20, and interleukin-2 receptor subunit β proteins (P ≤ .005). No significant association was detected between autophagy variants and OS or TTFT, suggesting that these variants drive disease initiation rather than progression. In conclusion, this study identified 4 novel associations for CLL and provided insights into the biological pathways that influence CLL development.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is an incurable disease1 that accounts for 25% to 35% of new leukemia cases in Europe and the United States.2,3 Although occasionally diagnosed in younger individuals (aged <55 years),4 the median age at diagnosis is 71 years. The advent of Bruton tyrosine kinase and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitors has improved the 5-year survival rate to ∼86%.5 Identified risk factors include age, sex, chemical exposure, European ancestry, and family history of hematological cancers.6 Prognostic factors, such as Rai and Binet staging, lymphocyte doubling time, CD38 and ZAP-70 expression, immunoglobulin mutation status, B-cell receptor stereotypy, cytogenetic changes, and gene mutations, are used in patient stratification.2 Still, despite the success of genome-wide association studies (GWASs) in uncovering susceptibility and prognostic loci for CLL,7-11 the etiopathogenesis of this heterogeneous disease remains poorly understood.

Recent studies implicate autophagy, a conserved catabolic process promoting cell survival, in CLL risk and prognosis.12-14 Autophagy contributes to malignant transformation and chemotherapeutic response, and has been observed in both hematological malignancies and solid tumors.7-11 In CLL, abnormal expressions of autophagy-related genes (BECN1, DAPK1, SLAMF1, GABARAPL2, ATG3, ATG5, ATG7, and TLR9) is linked to disease progression.15-21 Several reports show that autophagy has a prosurvival role, and its inhibition induces programmed cell death in CLL.12 These findings align with evidence of autophagy-apoptosis interplay in cancer and normal cells.22,23 However, a selective role of autophagy in CLL has been suggested, making it a potential therapeutic target. Conversely, a study in acute myeloid leukemia using Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1 knockout mice showed that autophagy induction helped overcome venetoclax resistance,24 a standard CLL therapy. Moreover, autophagy activation associates with better outcomes in other hematological cancers,25 suggesting a context-dependent function.

Given this, we investigated whether genetic variants in autophagy-related genes affect CLL risk across 4 European-ancestry populations. We also assessed their influence on time to first treatment (TTFT) and overall survival (OS). Lastly, considering autophagy’s role in immune modulation,26-29 we explored associations between these variants and autophagy flux in 67 healthy individuals, as well as immune traits in the 500FG cohort of the Human Functional Genomic Project (HFGP).30-32

Materials and methods

Discovery populations

The discovery populations included 4272 patients with CLL and 724 567 healthy controls from the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph; 3099 patients, 7666 controls), the FinnGen project (668 patients, 314 189 controls), and the UK Biobank (505 patients, 402 712 controls). CLL cases were diagnosed according to updated international criteria,2 and controls were randomly selected healthy individuals. The InterLymph cohort comprised 4 previous GWASs: National Cancer Institute (NCI) non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) GWAS,17 Utah CLL GWAS, Genetic Epidemiology of CLL Consortium GWAS,18 and University of California San Francisco Molecular Epidemiology of NHL GWAS.19 Patients were recruited via clinics, hospitals, cancer registries, or self-reports confirmed by medical and pathology records.

The InterLymph Data Coordinating Center reviewed International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes and pathology/medical data, classifying cases per the World Health Organization–based hierarchical system of the InterLymph Pathology Working Group (2008).33 Genotyping for InterLymph GWASs was conducted using the Illumina OmniExpress platform at the NCI Cancer Genomic Research Laboratory. Genotypes were called with Illumina GenomeStudio, and duplicate concordance exceeded 99%. Quality control excluded monomorphic single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and variants with call rate of <93%. Samples were removed if they had call rate of ≤93%, autosomal heterozygosity of <0.25 or >0.33, or sex discordance (>5% X chromosome heterozygosity in males, <20% in females). Unexpected duplicates (>99.9% concordance) and first-degree relatives (Pi-hat of >0.40) were also excluded. Ancestry was assessed via the genotype likelihoods (GLs) structure admix module following Pritchard et al,34 excluding individuals with <80% European ancestry.

Selection of SNPs and meta-analysis of discovery cohorts

A total of 234 autophagy-related genes were selected from the autophagy database (http://autophagy.lu/, accessed in November 2023; supplemental Table 1). Association estimates for 55 583 genotyped or imputed SNPs located within or near these genes (5 kilobases upstream, 3 kilobases downstream) were extracted from the discovery GWAS data sets and meta-analyzed using METAL.37 Genomic control was applied to correct for population stratification, and the I2 statistic assessed heterogeneity across studies. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using a fixed-effects model.

Of 55 583 variants, 49 612 SNPs were shared across all GWAS data sets and included in the association analysis. Among these, 1903 were considered common (minor allele frequency of > 0.05) and independent (r2 < 0.1) based on LDLink data for European populations (https://ldlink.nci.nih.gov/?tab=snpclip). A multiple testing significance threshold was set at P = 2.63 × 10−5 (0.05/1903 SNPs; supplemental Table 2).

Replication cohort, genotyping, and meta-analysis

After meta-analyzing GWAS data from InterLymph, UK Biobank, and FinnGen, we selected independent autophagy-related SNPs associated with CLL risk based on the following criteria: r2 < 0.1 (linkage disequilibrium threshold), P ≤ .0001, and no significant heterogeneity across populations (heterozygosity P ≥ .05). Previously reported CLL susceptibility SNPs were excluded. Eleven SNPs met these criteria and were advanced for replication in the CRuCIAL cohort, comprising 1200 patients with CLL and 1898 controls (supplemental Table 3).

The CRuCIAL study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centers. Details of the cohort are in supplemental Table 3. Genotyping was performed at the Centre for Genomics and Oncological Research, Granada, Spain, using KASPar assays (LGC Genomics, Middlesex, United Kingdom), following established protocols.38 For quality control, ∼5% of samples were genotyped in duplicate, showing ≥99.0% concordance. Genotype frequencies matched those in the 1000 Genomes database and were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Association analyses were conducted using STATA version 12.1, with statistical power estimated via Quanto version 12.4 (log-additive model). Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, and country of origin. Finally, we performed a meta-analysis combining CRuCIAL results with discovery cohorts using METAL,37 as described earlier.

OS and TTFT analyses in the CRuCIAL cohort

To assess the impact of autophagy-related variants on patient survival and disease progression, we evaluated associations between the selected SNPs and either OS or TTFT in the CRuCIAL cohort. The primary outcome was OS, defined as time from CLL diagnosis to death from any cause, with censoring at death or last follow-up. TTFT was defined as the time from diagnosis to first treatment or last follow-up. Associations with OS and TTFT were analyzed using Cox regression models adjusted for age, sex, and country of origin. Hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated for each SNP. For susceptibility analyses, the significance threshold was P = 2.63 × 10−5 (0.05/1903 SNPs; supplemental Table 2). Analyses were conducted using STATA version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and statistical power was calculated with the survSNP package in R (version 4.1.1; R Core Team, 2018).

Impact of autophagy-related variants on autophagy flux

We investigated whether autophagy-related SNPs were associated with autophagy flux in 68 healthy donors of European ancestry. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque and treated for 2 hours with 10 μM bafilomycin A1 (inhibitor) or 10 mM metformin (inducer). A total of 5 × 105 PBMCs were plated per well in 96-well round-bottom plates (Greiner) and treated with either metformin or bafilomycin A1, both, or left untreated. After treatment, cells were lysed in 50 μL of buffer (1% NP-40, 500 mM Tris HCl, 2.5 M NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, and phosphatase and protease inhibitors; pH 7.2). Twenty micrograms of protein were resolved by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Trans-Blot Turbo), blocked in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 with 5% bovine serum albumin, and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-LC3A/B, Cell Signaling; mouse anti-actin, Merck Millipore) diluted 1:1000 in 1% bovine serum albumin. After washing, secondary antibodies were applied (anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G) were applied. Detection was performed using SuperSignal West Femto (Thermo Fisher) or Clarity Western ECL (Bio-Rad), and images were captured with a ChemiDoc XRS system. Densitometry was done using Quantity One version 4.6.5 (Bio-Rad). Autophagy synthesis was calculated as the LC3-II ratio between metformin and Baf A1 and Baf A1–only conditions; degradation was assessed by comparing metformin with/without Baf A1. Analyses followed standard autophagy guidelines.39 Linear regression adjusted for age and sex tested SNP–flux associations, with a significance set at P = .01 (5 SNPs, 2 treatments).

Functional effect of the autophagy-related variants on immune responses

To explore the functional relevance of SNPs that remained significant after correction for multiple testing (P = 2.63 × 10−5), as well as known CLL susceptibility loci, we assessed their association with cytokine expression quantitative trait loci (cQTL) data from in vitro stimulation experiments in 408 healthy individuals from the 500FG cohort of the HFGP.

cQTL data included levels of interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor α, IL-17, and IL-22 measured in PBMCs, monocyte-derived macrophages, or whole blood after 24-hour stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (1 or 100 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), phytohemagglutinin (10 μg/mL; Sigma), N-palmitoyl-S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(R)-propyl]-cysteine (Pam3Cys; 10 μg/mL; EMC Microcollections), or cytosine-phosphate-guanine (100 ng/mL; InvivoGen), or in unstimulated conditions. Cytokine concentrations were determined using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (PeliKine Compact or R&D Systems), following manufacturer instructions. For values outside detection limits, the respective limit was assigned. After log transformation, linear regression analyses adjusted for age and sex were used to assess associations between selected SNPs and cytokine levels. Detailed protocols for PBMC isolation, macrophage differentiation, and stimulation assays have been described previously.31,40

Association of autophagy SNPs and blood cell counts and serum/plasma proteomic profiles

To assess the impact of selected SNPs on immune cell variation, 91 blood-derived cell populations were quantified by 10-color flow cytometry (Navios, Beckman Coulter) within 2 to 3 hours of sampling. Cell populations were analyzed using Kaluza software (version 1.3), and interexperimental noise was minimized by calculating parental and grandparental percentages, that is, the proportion of a given cell type within its immediate or ancestral subset (supplemental Table 4). Detailed protocols for cell isolation, reagents, gating, and flow cytometry have been published elsewhere.41

Proteomic profiling was also performed on serum and plasma samples from the HFGP cohort using the Olink inflammation panel (Olink, Sweden), which quantified 103 circulating proteins (supplemental Table 5). Protein levels were log2 transformed and normalized using bridging samples to adjust for batch effects.

To correct for multiple testing, significance thresholds were set at 2.92 × 10−4 for cQTL, 2.55 × 10−5 for proteomic, and 2.89 × 10−5 for cell count analyses. Methodological details for all functional assays are available in previous publications.30-32,40 Analyses were performed in R (http://www.r-project.org) using custom scripts, and plots were generated with Prism.

In silico functional analysis

We used Haploreg (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg.php) to predict the functional roles of autophagy-related SNPs. Their potential as expression QTL across tissues was assessed using genotype-tissue expression project (GTEx; https://gtexportal.org/home/), and broader QTL features were explored via QTLbase (http://www.mulinlab.org/qtlbase), which compiles data from GTEx, the Cancer Genome Atlas, Database of Immune Cell Expression, and others. To complement these analyses, meta-scores integrating conservation, allele frequency, and predicted protein impact were generated. Additional functional evaluation included combined annotation-dependent depletion,42 RegulomeDB (https://regulomedb.org/), and FORGEdb (https://forge2.altiusinstitute.org/files/forgedb.html).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from each participating institution for the InterLymph, UK Biobank, and FinnGen GWASs. In addition, the CRuCIAL study was approved by the ethical review committee of participant institutions: Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital (Granada, Spain, 0760-N-18); University Hospital of Salamanca (Salamanca, Spain, PI90/07/2018); Hospital del Mar (Barcelona, Spain); Catalan Institute of Oncology (Barcelona, Spain); Morales Meseguer University Hospital (Murcia, Spain); Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP) group (Spain); University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, AOU Policlinico (Modena, Italy); University of Pisa (Pisa, Italy), Wroclaw Medical University (Wroclaw, Poland); and the Radboud University Medical Center (Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2011/299). A detailed description of the study cohort has been reported elsewhere.2 All participants provided written informed consent to participate in these genetic studies. The HFGP study was approved by the Arnhem-Nijmegen ethical committee (no. 42561.091.12) and biological specimens were collected after informed consent was obtained.

Results

This study followed a 2-phase design combining discovery and validation stages. In the discovery phase, we performed a meta-analysis of 3 large European cohorts (InterLymph, UK Biobank, and FinnGen), including 4272 CLL cases and 724 567 healthy controls. This analysis identified multiple SNPs significantly associated with CLL risk. The strongest associations were observed for the FASrs1926194, BAK1rs210143, and BCL2rs4987852 SNPs (OR = 1.29, P = 4.73 × 10−21; OR = 1.20, P = 3.39 × 10−9; and OR = 1.38, P = 5.40 × 10−12, respectively), which served as internal positive controls and remained statistically significant in the combined analysis. In addition to these previously reported loci, another 11 independent variants including BCL2rs1026825, BCL2rs11152374, BCL2rs12457371, BCL2rs4940571, BCL2rs7236090, CDKN2Ars3731204, EGFRrs4947976, LPAR6|RB1rs11839271, NAF1rs6829366, PRKCDrs143052840, and TFEBrs6910366 also showed notable associations and were selected for replication based on their statistical significance, effect sizes, independence, and low between-study heterogeneity (Table 1).

Meta-analysis of the autophagy-related risk variants for CLL in the discovery cohorts

| SNP . | Gene . | Chr . | Effect allele . | InterLymph cohort . | UK Biobank . | FinnGen Risteys 10 . | Discovery meta-analysis . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 3099 CLL cases and 7666 healthy controls) . | (N = 505 CLL cases and 402 712 healthy controls) . | (N = 668 CLL cases 314 189 healthy controls) . | (N = 4272 CLL cases and 724 567 healthy controls) . | |||||||||

| OR (95% CI) . | P value . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | phet . | ||||

| rs59952010 | ARSB | 5 | T | 1.13 (1.06-1.21) | 2.16 × 10−4 | 1.17 (1.03-1.34) | .020 | 1.05 (0.93-1.19) | .418 | 1.13 (1.06-1.19) | 6.29 × 10−5 | 0.831 |

| rs210143 | BAK1 | 6 | C | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) | 9.52 × 10–8 | 1.08 (0.94-1.24) | .260 | 1.29 (1.13-1.48) | 1.65 × 10−4 | 1.20 (1.13-1.27) | 3.39 × 10−9 | 0.083 |

| rs4987852 | BCL2 | 18 | C | 1.43 (1.28-1.61) | 1.61 × 10−9 | 1.06 (0.84-1.34) | .640 | 1.47 (1.27-1.72) | 5.30 × 10−7 | 1.38 (1.26-1.51) | 5.40 × 10−12 | 0.148 |

| rs4987856 | BCL2 | 18 | T | 0.69 (0.66-0.77) | 3.55 × 10−11 | 0.75 (0.60-0.93) | 7.50 × 10−3 | 0.87 (0.68-1.11) | .249 | 0.72 (0.66-0.80) | 7.35 × 10−11 | 0.518 |

| rs1026825 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 1.09 (1.03-1.16) | 4.08 × 10−3 | 1.21 (1.07-1.37) | 3.50 × 10−3 | 1.10 (0.99-1.23) | .078 | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | 6.62 × 10−5 | 0.672 |

| rs11152374 | BCL2 | 18 | A | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) | 3.72 × 10−3 | 1.15 (0.99-1.34) | .078 | 1.09 (0.97-1.24) | .159 | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | 5.42 × 10−4 | 0.377 |

| rs4940571 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 1.20 (1.08-1.34) | 9.11 × 10−4 | 1.19 (0.96-1.47) | .120 | 1.13 (0.96-1.34) | .143 | 1.18 (1.08-1.29) | 3.05 × 10−4 | 0.969 |

| rs7236090 | BCL2 | 18 | C | 1.10 (1.03-1.17) | 3.84 × 10−3 | 1.16 (1.02-1.32) | .017 | 1.09 (0.98-1.22) | .121 | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | 1.92 × 10−4 | 0.896 |

| rs12457371 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 0.89 (0.83-0.94) | 3.66 × 10−4 | 0.91 (0.79-1.05) | .210 | 0.86 (0.77-0.97) | .010 | 0.88 (0.83-0.93) | 2.77 × 10−5 | 0.988 |

| rs3731204 | CDKN2A | 9 | C | 0.79 (0.72-0.87) | 4.42 × 10−7 | 0.76 (0.64-0.91) | 2.90 × 10−3 | 0.76 (0.63-0.91) | 3.41 × 10−3 | 0.78 (0.72-0.85) | 1.03 × 10−9 | 0.972 |

| rs4947976 | EGFR | 7 | A | 1.03 (0.97-1.09) | .383 | 1.22 (1.08-1.38) | 2.40 × 10−3 | 1.12 (1.01-1.25) | .039 | 1.15 (1.07-1.24) | 1.15 × 10−4 | 0.780 |

| rs1926194 | FAS | 10 | A | 1.27 (1.19-1.35) | 1.15 × 10−13 | 1.32 (1.16-1.50) | 1.70 × 10−5 | 1.34 (1.20-1.50) | 1.61 × 10−7 | 1.29 (1.23-1.36) | 4.73 × 10−21 | 0.145 |

| rs7584971 | ITGA6 | 2 | A | 1.01 (0.93-1.11) | .800 | 1.20 (1.00-1.44) | .050 | 1.22 (1.08-1.38) | 1.14 × 10−3 | 1.17 (1.07-1.29) | 6.07 × 10−4 | 0.578 |

| rs11839271 | LPAR6, RB1 | 13 | T | 0.90 (0.84-0.96) | 2.28 × 10−3 | 0.92 (0.80-1.05) | .220 | 0.89 (0.79-1.00) | .052 | 0.90 (0.85-0.96) | 4.34 × 10−4 | 0.991 |

| rs6829366 | NAF1 | 4 | T | 1.13 (1.05-1.21) | 1.49 × 10−3 | 1.16 (1.00-1.35) | .055 | 1.05 (0.91-1.21) | .478 | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | 4.26 × 10−4 | 0.022 |

| rs143052840 | PRKCD | 3 | A | 1.25 (1.09-1.44) | 1.14 × 10−3 | 1.54 (1.19-1.98) | 7.30 × 10−4 | 0.96 (0.72-1.29) | .786 | 1.26 (1.11-1.42) | 1.80 × 10−4 | 0.339 |

| rs6910366 | TFEB | 6 | G | 0.83 (0.76-0.91) | 5.11 × 10−5 | 0.84 (0.70-1.02) | .068 | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) | .429 | 0.86 (0.80-0.93) | 8.28 × 10−5 | 0.850 |

| rs2645488 | VMP1 | 17 | G | 1.14 (1.07-1.22) | 1.60 × 10−4 | 1.19 (1.03-1.36) | .017 | 0.95 (0.85-1.07) | .403 | 1.11 (1.04-1.18) | 7.71 × 10−4 | 0.043 |

| rs17885803 | WRAP53, TP53 | 17 | T | 1.27 (1.11-1.44) | 2.93 × 10−4 | 1.36 (1.06-1.76) | .017 | 1.10 (0.93-1.31) | .265 | 1.22 (1.11-1.36) | 1.10 × 10−4 | 0.480 |

| SNP . | Gene . | Chr . | Effect allele . | InterLymph cohort . | UK Biobank . | FinnGen Risteys 10 . | Discovery meta-analysis . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 3099 CLL cases and 7666 healthy controls) . | (N = 505 CLL cases and 402 712 healthy controls) . | (N = 668 CLL cases 314 189 healthy controls) . | (N = 4272 CLL cases and 724 567 healthy controls) . | |||||||||

| OR (95% CI) . | P value . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | phet . | ||||

| rs59952010 | ARSB | 5 | T | 1.13 (1.06-1.21) | 2.16 × 10−4 | 1.17 (1.03-1.34) | .020 | 1.05 (0.93-1.19) | .418 | 1.13 (1.06-1.19) | 6.29 × 10−5 | 0.831 |

| rs210143 | BAK1 | 6 | C | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) | 9.52 × 10–8 | 1.08 (0.94-1.24) | .260 | 1.29 (1.13-1.48) | 1.65 × 10−4 | 1.20 (1.13-1.27) | 3.39 × 10−9 | 0.083 |

| rs4987852 | BCL2 | 18 | C | 1.43 (1.28-1.61) | 1.61 × 10−9 | 1.06 (0.84-1.34) | .640 | 1.47 (1.27-1.72) | 5.30 × 10−7 | 1.38 (1.26-1.51) | 5.40 × 10−12 | 0.148 |

| rs4987856 | BCL2 | 18 | T | 0.69 (0.66-0.77) | 3.55 × 10−11 | 0.75 (0.60-0.93) | 7.50 × 10−3 | 0.87 (0.68-1.11) | .249 | 0.72 (0.66-0.80) | 7.35 × 10−11 | 0.518 |

| rs1026825 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 1.09 (1.03-1.16) | 4.08 × 10−3 | 1.21 (1.07-1.37) | 3.50 × 10−3 | 1.10 (0.99-1.23) | .078 | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | 6.62 × 10−5 | 0.672 |

| rs11152374 | BCL2 | 18 | A | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) | 3.72 × 10−3 | 1.15 (0.99-1.34) | .078 | 1.09 (0.97-1.24) | .159 | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | 5.42 × 10−4 | 0.377 |

| rs4940571 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 1.20 (1.08-1.34) | 9.11 × 10−4 | 1.19 (0.96-1.47) | .120 | 1.13 (0.96-1.34) | .143 | 1.18 (1.08-1.29) | 3.05 × 10−4 | 0.969 |

| rs7236090 | BCL2 | 18 | C | 1.10 (1.03-1.17) | 3.84 × 10−3 | 1.16 (1.02-1.32) | .017 | 1.09 (0.98-1.22) | .121 | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | 1.92 × 10−4 | 0.896 |

| rs12457371 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 0.89 (0.83-0.94) | 3.66 × 10−4 | 0.91 (0.79-1.05) | .210 | 0.86 (0.77-0.97) | .010 | 0.88 (0.83-0.93) | 2.77 × 10−5 | 0.988 |

| rs3731204 | CDKN2A | 9 | C | 0.79 (0.72-0.87) | 4.42 × 10−7 | 0.76 (0.64-0.91) | 2.90 × 10−3 | 0.76 (0.63-0.91) | 3.41 × 10−3 | 0.78 (0.72-0.85) | 1.03 × 10−9 | 0.972 |

| rs4947976 | EGFR | 7 | A | 1.03 (0.97-1.09) | .383 | 1.22 (1.08-1.38) | 2.40 × 10−3 | 1.12 (1.01-1.25) | .039 | 1.15 (1.07-1.24) | 1.15 × 10−4 | 0.780 |

| rs1926194 | FAS | 10 | A | 1.27 (1.19-1.35) | 1.15 × 10−13 | 1.32 (1.16-1.50) | 1.70 × 10−5 | 1.34 (1.20-1.50) | 1.61 × 10−7 | 1.29 (1.23-1.36) | 4.73 × 10−21 | 0.145 |

| rs7584971 | ITGA6 | 2 | A | 1.01 (0.93-1.11) | .800 | 1.20 (1.00-1.44) | .050 | 1.22 (1.08-1.38) | 1.14 × 10−3 | 1.17 (1.07-1.29) | 6.07 × 10−4 | 0.578 |

| rs11839271 | LPAR6, RB1 | 13 | T | 0.90 (0.84-0.96) | 2.28 × 10−3 | 0.92 (0.80-1.05) | .220 | 0.89 (0.79-1.00) | .052 | 0.90 (0.85-0.96) | 4.34 × 10−4 | 0.991 |

| rs6829366 | NAF1 | 4 | T | 1.13 (1.05-1.21) | 1.49 × 10−3 | 1.16 (1.00-1.35) | .055 | 1.05 (0.91-1.21) | .478 | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | 4.26 × 10−4 | 0.022 |

| rs143052840 | PRKCD | 3 | A | 1.25 (1.09-1.44) | 1.14 × 10−3 | 1.54 (1.19-1.98) | 7.30 × 10−4 | 0.96 (0.72-1.29) | .786 | 1.26 (1.11-1.42) | 1.80 × 10−4 | 0.339 |

| rs6910366 | TFEB | 6 | G | 0.83 (0.76-0.91) | 5.11 × 10−5 | 0.84 (0.70-1.02) | .068 | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) | .429 | 0.86 (0.80-0.93) | 8.28 × 10−5 | 0.850 |

| rs2645488 | VMP1 | 17 | G | 1.14 (1.07-1.22) | 1.60 × 10−4 | 1.19 (1.03-1.36) | .017 | 0.95 (0.85-1.07) | .403 | 1.11 (1.04-1.18) | 7.71 × 10−4 | 0.043 |

| rs17885803 | WRAP53, TP53 | 17 | T | 1.27 (1.11-1.44) | 2.93 × 10−4 | 1.36 (1.06-1.76) | .017 | 1.10 (0.93-1.31) | .265 | 1.22 (1.11-1.36) | 1.10 × 10−4 | 0.480 |

Estimates calculated according to a log-additive model of inheritance and adjusted for age, sex and country of origin. The meta-analysis was performed assuming a fixed-effect model using METAL. P < 2.63E−5 in bold.

Chr, chromosome.

In the replication phase, these 11 SNPs were tested in an independent cohort (CRuCIAL), consisting of 1200 CLL cases and 1898 controls. Interestingly, the CDKN2Ars3731204 and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs showed consistent directions of effect compared with the discovery phase and replicated with nominal significance (OR = 0.80, P = 8.72 × 10−3; OR = 1.40, P = 8.66 × 10−4, respectively), whereas some SNPs such as BCL2rs1026825 (OR = 1.06, P = .353) and BCL2rs12457371 (OR = 0.92, P = .294) showed the same direction but did not reach statistical significance (Table 1).

The meta-analysis of these 4 independent populations confirmed novel and statistically significant associations of CDKN2Ars3731204, BCL2rs1026825, BCL2rs12457371, and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs with CLL risk (OR = 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.84; P = 1.57 × 10−12; OR = 1.11; 95% CI, 1.06-1.16; P = 1.75 × 10−5; OR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84-0.93; P = 3.69 × 10−6; and OR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.12-1.31; P = 3.25 × 10−6; respectively; Table 2).

Overall meta-analysis of association estimates of autophagy-related risk variants for CLL

| SNP . | Gene . | Chr . | Effect allele . | Discovery meta-analysis . | CRuCIAL cohort . | Overall meta-analysis . | References (PMID) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 724 567 healthy controls; 4272 CLL cases) . | (N = 1898 healthy controls; 1200 CLL cases) . | (N = 726 465 healthy controls; 5472 CLL cases) . | ||||||||||

| OR (95% CI) . | P value . | PHet . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | PHet . | |||||

| rs59952010 | ARSB | 5 | T | 1.13 (1.06-1.19) | 6.29E−05 | 0.831 | – | – | – | – | – | 26956414 |

| rs210143 | BAK1 | 6 | C | 1.20 (1.13-1.27) | 3.39E−09 | 0.083 | – | – | – | – | – | 22700719; 24292274; 23770605; 28165464 |

| rs4987852 | BCL2 | 18 | C | 1.38 (1.26-1.51) | 5.40E−12 | 0.148 | – | – | – | – | – | 23770605 |

| rs4987856 | BCL2 | 18 | T | 0.72 (0.66-0.80) | 7.35E−11 | 0.518 | – | – | – | – | – | 26956414; 23770605 |

| rs1026825 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | 6.62E−05 | 0.672 | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) | .353 | 1.11 (1.06-1.16) | 1.75E−05 | 0.698 | – |

| rs11152374 | BCL2 | 18 | A | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | 5.42E−04 | 0.377 | 0.97 (0.84-1.13) | .716 | 1.10 (1.04-1.16) | 1.13E−03 | 0.193 | – |

| rs11839271 | LPAR6, RB1 | 13 | T | 0.90 (0.85-0.96) | 4.34E−04 | 0.991 | 1.13 (0.96-1.33)∗ | .131 | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) | 1.63E−03 | 0.268 | – |

| rs12457371 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 0.88 (0.83-0.93) | 2.77E−05 | 0.988 | 0.92 (0.78-1.08) | .294 | 0.89 (0.84-0.93) | 3.69E−06 | 0.989 | – |

| rs143052840 | PRKCD | 3 | A | 1.26 (1.11-1.42) | 1.80E−04 | 0.339 | 0.82 (0.62-1.00)∗ | .152 | 1.18 (1.06-1.31) | 1.59E−03 | 0.027 | – |

| rs3731204 | CDKN2A | 9 | C | 0.78 (0.72-0.85) | 1.03E−09 | 0.972 | 0.80 (0.67-0.94) | 8.72E−03 | 0.78 (0.73-0.84) | 1.57E−12 | 0.982 | – |

| rs4940571 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 1.18 (1.08-1.29) | 3.05E−04 | 0.969 | 1.40 (1.15-1.71) | 8.66E−04 | 1.21 (1.12-1.31) | 3.25E−06 | 0.445 | – |

| rs1926194 | FAS | 10 | A | 1.29 (1.23-1.36) | 4.73E−21 | 0.145 | – | – | – | – | – | 24292274; 26956414; 28165464 |

| rs7584971 | ITGA6 | 2 | A | 1.17 (1.07-1.29) | 6.07E−04 | 0.578 | – | – | – | – | – | 32887889 |

| rs4947976 | EGFR | 7 | A | 1.15 (1.07-1.24) | 1.15E−04 | 0.780 | 1.02 (0.91-1.14)† | .723 | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | 4.04E−04 | 0.360 | – |

| rs6829366 | NAF1 | 4 | T | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | 4.26E−04 | 0.022 | 1.14 (0.98-1.31) | .087 | 1.12 (1.06-1.19) | 5.73E−05 | 0.024 | – |

| rs6910366 | TFEB | 6 | G | 0.86 (0.80-0.93) | 8.28E−05 | 0.850 | 1.07 (0.85-1.33)∗ | .574 | 0.87 (0.82-0.93) | 8.74E−05 | 0.474 | – |

| rs7236090 | BCL2 | 18 | C | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | 1.92E−04 | 0.896 | 0.99 (0.88-1.12) | .912 | 1.10 (1.04-1.15) | 1.83E−04 | 0.746 | – |

| rs2645488 | VMP1 | 17 | G | 1.11 (1.04-1.18) | 7.71E−04 | 0.043 | – | – | – | – | – | 31407831 |

| rs17885803 | WRAP53, TP53 | 17 | T | 1.22 (1.11-1.36) | 1.10E−04 | 0.480 | – | – | – | – | – | 32887889 |

| SNP . | Gene . | Chr . | Effect allele . | Discovery meta-analysis . | CRuCIAL cohort . | Overall meta-analysis . | References (PMID) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 724 567 healthy controls; 4272 CLL cases) . | (N = 1898 healthy controls; 1200 CLL cases) . | (N = 726 465 healthy controls; 5472 CLL cases) . | ||||||||||

| OR (95% CI) . | P value . | PHet . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | PHet . | |||||

| rs59952010 | ARSB | 5 | T | 1.13 (1.06-1.19) | 6.29E−05 | 0.831 | – | – | – | – | – | 26956414 |

| rs210143 | BAK1 | 6 | C | 1.20 (1.13-1.27) | 3.39E−09 | 0.083 | – | – | – | – | – | 22700719; 24292274; 23770605; 28165464 |

| rs4987852 | BCL2 | 18 | C | 1.38 (1.26-1.51) | 5.40E−12 | 0.148 | – | – | – | – | – | 23770605 |

| rs4987856 | BCL2 | 18 | T | 0.72 (0.66-0.80) | 7.35E−11 | 0.518 | – | – | – | – | – | 26956414; 23770605 |

| rs1026825 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | 6.62E−05 | 0.672 | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) | .353 | 1.11 (1.06-1.16) | 1.75E−05 | 0.698 | – |

| rs11152374 | BCL2 | 18 | A | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | 5.42E−04 | 0.377 | 0.97 (0.84-1.13) | .716 | 1.10 (1.04-1.16) | 1.13E−03 | 0.193 | – |

| rs11839271 | LPAR6, RB1 | 13 | T | 0.90 (0.85-0.96) | 4.34E−04 | 0.991 | 1.13 (0.96-1.33)∗ | .131 | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) | 1.63E−03 | 0.268 | – |

| rs12457371 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 0.88 (0.83-0.93) | 2.77E−05 | 0.988 | 0.92 (0.78-1.08) | .294 | 0.89 (0.84-0.93) | 3.69E−06 | 0.989 | – |

| rs143052840 | PRKCD | 3 | A | 1.26 (1.11-1.42) | 1.80E−04 | 0.339 | 0.82 (0.62-1.00)∗ | .152 | 1.18 (1.06-1.31) | 1.59E−03 | 0.027 | – |

| rs3731204 | CDKN2A | 9 | C | 0.78 (0.72-0.85) | 1.03E−09 | 0.972 | 0.80 (0.67-0.94) | 8.72E−03 | 0.78 (0.73-0.84) | 1.57E−12 | 0.982 | – |

| rs4940571 | BCL2 | 18 | G | 1.18 (1.08-1.29) | 3.05E−04 | 0.969 | 1.40 (1.15-1.71) | 8.66E−04 | 1.21 (1.12-1.31) | 3.25E−06 | 0.445 | – |

| rs1926194 | FAS | 10 | A | 1.29 (1.23-1.36) | 4.73E−21 | 0.145 | – | – | – | – | – | 24292274; 26956414; 28165464 |

| rs7584971 | ITGA6 | 2 | A | 1.17 (1.07-1.29) | 6.07E−04 | 0.578 | – | – | – | – | – | 32887889 |

| rs4947976 | EGFR | 7 | A | 1.15 (1.07-1.24) | 1.15E−04 | 0.780 | 1.02 (0.91-1.14)† | .723 | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | 4.04E−04 | 0.360 | – |

| rs6829366 | NAF1 | 4 | T | 1.12 (1.05-1.20) | 4.26E−04 | 0.022 | 1.14 (0.98-1.31) | .087 | 1.12 (1.06-1.19) | 5.73E−05 | 0.024 | – |

| rs6910366 | TFEB | 6 | G | 0.86 (0.80-0.93) | 8.28E−05 | 0.850 | 1.07 (0.85-1.33)∗ | .574 | 0.87 (0.82-0.93) | 8.74E−05 | 0.474 | – |

| rs7236090 | BCL2 | 18 | C | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | 1.92E−04 | 0.896 | 0.99 (0.88-1.12) | .912 | 1.10 (1.04-1.15) | 1.83E−04 | 0.746 | – |

| rs2645488 | VMP1 | 17 | G | 1.11 (1.04-1.18) | 7.71E−04 | 0.043 | – | – | – | – | – | 31407831 |

| rs17885803 | WRAP53, TP53 | 17 | T | 1.22 (1.11-1.36) | 1.10E−04 | 0.480 | – | – | – | – | – | 32887889 |

Estimates calculated according to a log-additive model of inheritance and adjusted for age and sex. Meta-analysis was performed assuming a fixed-effect model using METAL software. P < 2.63E−05 in bold.

Chr, Chromosome; PHet, P value for heterogeneity.

Association estimates was calculated in a subset of 1 055 healthy controls and 1 024 CLL cases from the CRuCIAL cohort.

Authors report the effect found for the rs12718945 (an SNP in complete linkage disequilibrium with the rs4947976, r2 = 0.996).

The most statistically significant effect on CLL risk was found for CDKN2Ars3731204 SNP within the CDKN2A locus. Each copy of CDKN2Ars3731204C allele decreased the risk of developing CLL by 22%. According to the GTEx data, the CDKN2Ars3731204C allele was strongly associated with higher levels of CDKN2A messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels in whole blood (P = 5.1 × 10−7; supplemental Figure 1A). In addition, although this SNP was not significantly associated with autophagy flux levels (P > .01), our functional experiments revealed, to our knowledge, for the first time, an association between the CDKN2Ars3731204C protective allele and decreased absolute numbers of CD45RO-CD45RA+ effector T cells and CD4+CD8+ T cells (P = .0027 and P = .0036; Figure 1A-B). Moreover, we found that carriers of the CDKN2Ars3731204C protective allele had increased levels of IFN-γ after stimulation of whole blood with phytohemagglutinin (P = .0040; Figure 1C), suggesting a functional role of this SNP in CLL risk through modulation of CDKN2A protein levels and specific subsets of immune cells.

Functional impact of the CDKN2Ars3731204 SNP. Association of the CDKN2Ars3731204 SNP with absolute numbers of specific subsets of T cells (A and B) and IFN-γ levels after in vitro stimulation of WB with PHA (C). NS, nonsignificant; PHA, phytohemagglutinin; WB, whole blood.

Functional impact of the CDKN2Ars3731204 SNP. Association of the CDKN2Ars3731204 SNP with absolute numbers of specific subsets of T cells (A and B) and IFN-γ levels after in vitro stimulation of WB with PHA (C). NS, nonsignificant; PHA, phytohemagglutinin; WB, whole blood.

In addition to the association of CDKN2A SNP with CLL risk, we found novel and statistically significant associations for BCL2rs1026825, BCL2rs12457371, and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs with CLL risk (Table 2). These associations were independent of those previously reported in this locus (rs4987852 and rs4987856). Intriguingly, we found no association between BCL2 SNPs and autophagic flux levels. However, carriers of the BCL2rs4940571G risk allele had increased absolute numbers of FOXP3+Helios+ regulatory T (Treg) cells (P = .005; Figure 2A) and decreased circulating concentrations of IFN-γ (P = .0044; Figure 2B). In contrast, we found that carriers of the BCL2rs1026825G risk allele had increased absolute numbers of CD4+CD25+CD127low Treg cells (P = .0036; Figure 2C) and decreased circulating concentrations of IL-2 receptor subunit β (P = .0058; Figure 2D). In addition, we found that carriers of the BCL2rs1026825G risk allele had increased production of IL-6 after in vitro stimulation of PBMCs with Pam3Cys (P = .0036; Figure 2E). In silico analysis also revealed that this SNP is strongly associated with a chromatin accessibility QTL in lymphocytes (P = 4.15 × 10−7). Although none of the functional findings performed in the HFGP cohort were significant after correction for multiple testing, these results suggest that BCL2rs4940571 and BCL2rs1026825 SNPs might influence CLL risk by determining the absolute numbers of Treg cells, IL-6–mediated immune responses, and changes in chromatin accessibility.

Functional impact of the BCL2rs1026825 and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs. Association of the BCL2rs1026825 and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs with absolute numbers of specific subsets of T cells and regulatory T cells, circulating concentrations of inflammatory proteins (IFN-γ and IL-2 receptor subunit β) and IL-6 levels after stimulation of PBMCs with Pam3Cys. NS, nonsignificant; Pam3Cys, N-palmitoyl-S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(R)-propyl]-cysteine.

Functional impact of the BCL2rs1026825 and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs. Association of the BCL2rs1026825 and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs with absolute numbers of specific subsets of T cells and regulatory T cells, circulating concentrations of inflammatory proteins (IFN-γ and IL-2 receptor subunit β) and IL-6 levels after stimulation of PBMCs with Pam3Cys. NS, nonsignificant; Pam3Cys, N-palmitoyl-S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(R)-propyl]-cysteine.

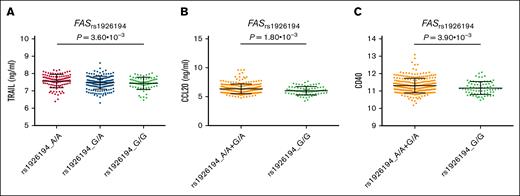

In addition to these novel findings, the meta-analysis of the 4 European populations also validated previously reported associations with CLL risk for 4 genetic variants within FAS, BCL2, and BAK1 (Table 2). As expected, all of these associations remained significant after correction for multiple testing. In GTEx, the FASrs1926194A risk allele is strongly associated with actin-α2 (ACTA2) mRNA expression levels in whole blood and lymphocytes (P = 7.8 × 10−41 and P = 1.58 × 10−21, respectively; supplemental Figure 1B), which suggest that this SNP might influence CLL risk through the modulation of gene expression of ACTA2, a well-known susceptibility locus for CLL. Interestingly, although we failed to find a significant association between this SNP and autophagy flux levels (P > .01; supplemental Table 6), we found in the HFGP that the healthy carriers of the FASrs1926194A risk allele had increased circulating concentrations of tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), chemokine ligand 20, and CD40 (P = .0036, P = .0018, and P = .0039, respectively; Figure 3). Although none of these functional findings remained significant after multiple testing corrections, they suggested that this genetic variant may modulate the risk of CLL through host immune-mediated mechanisms. No functional effect for the BCL2rs4987852, BCL2rs4987856, and BAK1rs210143 SNPs was found in relation to autophagy flux or immune responses, suggesting that the effect of these SNPs on CLL risk is not mediated by these mechanisms.

Functional impact of FASrs1926194 SNP. Association of the FASrs1926194 SNP with circulating concentrations of TRAIL, CCL20, and CD40. CCL20, chemokine ligand 20.

Functional impact of FASrs1926194 SNP. Association of the FASrs1926194 SNP with circulating concentrations of TRAIL, CCL20, and CD40. CCL20, chemokine ligand 20.

Finally, given the noticeable impact of autophagy-related SNPs on CLL risk and the known role of CDKN2A and BCL2 in determining tumor progression and drug response in many cancer types,1 we tested whether selected autophagy-related SNPs could influence the OS of patients with CLL and TTFT in the CRuCIAL cohort. Our results showed no association between autophagy-related variants and either OS or TTFT (supplemental Tables 7 and 8). We only found a modest association of the TFEBrs6910366 SNP with longer OS (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52-0.94; P = .016) and an association of the BCL2rs4940571 SNP with shorter TTFT (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.01-2.04; P = .046). Neither association remained significant after multiple testing corrections, suggesting that autophagy-related SNPs do not have a strong effect on patient survival or disease progression.

Discussion

This comprehensive study found, to our knowledge, for the first time that the CDKN2A locus is a susceptibility gene for CLL. In addition, this study identified 3 new susceptibility SNPs within BCL2 that were independent of those previously reported at this locus. These results confirm the important role of BCL2 in modulating CLL risk.

The most significant effect on CLL risk was found for CDKN2Ars3731204 SNP, which lies in the second intron of CDKN2A, a tumor suppressor gene that regulates key biological processes such as B-cell division, cell differentiation, autophagy, and cell death. CDKN2A encodes a cell-cycle inhibitor protein (p16CDKN2A), which impedes abnormal cell growth and proliferation by binding to complexes of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) 4 and 6, and cyclin D, which leads to cell cycle arrest in the G1/S phase.43 Both common and rare germ line variants or deletions within CDKN2A have been consistently associated with melanoma44 and endocrine pancreatic cancer,45 as well as blood cancers such as multiple myeloma,40 acute lymphocytic leukemia,46 and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.47

In this study, we found that carriers of the CDKN2Ars3731204C allele (associated with higher CDKN2A mRNA expression levels according to the GTEx data) had a decreased risk of developing CLL. This finding agreed with previous results, suggesting that the loss of function of CDKN2A might lead to autophagy deregulation48 and cancer development through inactivation of destabilization of the p53 protein, which increases cell division rates and inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis. In line with this hypothesis, Haploreg and QTLbase data showed that the CDKN2Ars3731204 SNP maps on histone marks (H3K4me1 and H3K4me3) in multiple immune cell types and alters binding sites for key transcription factors such as DMRT1-7, HDAC2, FOXD3, and Evi1, which play important roles in epigenetic repression, chromatin structure and transcriptional regulation, cell cycle progression, developmental events, and CLL progression. In addition, we found that healthy individuals carrying the CDKN2Ars3731204C protective allele had decreased numbers of CD45RO−CD45RA+ naïve T cells in the blood, which were found to be enriched in patients with CLL with advanced Rai stages (III or IV).49 In addition, it has been observed that these cells are unresponsive to tumor antigens, which might indicate that these cells act as drivers of disease onset and progression. In contrast, we observed that carriers of the CDKN2Ars3731204C allele had decreased numbers of double CD4+CD8+ T cells, which are a type of T cell frequently found in patients with CLL with an active disease.50 Although no definitive proof exists, it has been proposed that these cells are involved in CLL progression.51 In agreement with the hypothesis suggesting a role of the CDKN2A gene in determining host immunity, previous studies have reported that the CDKN2A gene shapes T cell– and macrophage-mediated immune responses in different types of cancer52-54 and even mediates responses to immunotherapies.55,56 Given that we did not find a significant association between the CDKN2Ars3731204 SNP and autophagy flux levels, it seems plausible that this SNP influences the risk of CLL by modulating the absolute numbers of specific T-cell subsets rather than through the control of the autophagy pathway.

Another interesting result was the association between CLL risk and 3 independent SNPs within the BCL2 gene. The BCL2 locus is a well-known susceptibility gene for CLL that encodes a protein that regulates apoptosis. Intriguingly, in contrast to many other oncogenes, BCL2 does not promote cell proliferation but induces cell survival.57 Although t(14;18) translocation affecting BCL2 has been associated with the development of B-cell leukemias and lymphomas, multiple studies have demonstrated that the high expression of BCL2 mRNA observed in most patients with CLL58,59 is not strictly dependent on t14;18 translocation.60 Interestingly, the newly identified variants within the BCL2 gene (rs1026825, rs12457371, and rs4940571) were independent of each other (r2 < 0.1) and of those previously reported within this locus (rs4987852 and rs4987855),61 which confirmed the importance of BCL2 in modulating the risk of CLL but also the difficulties in deciphering its complex genomic regulation and its role in CLL. Although multiple mechanisms have been proposed, including promoter hypomethylation,62 loss of microRNA-15 and microRNA-16 expression,63 overexpression of nucleolin,64 or even the existence of a 5′–untranslated region open reading frame that might repress BCL2 mRNA expression,65 the mechanism that drives BCL2 expression in CLL remains unknown to date. Our functional experiments revealed no significant effect of BCL2 SNPs on modulating autophagic flux levels. However, we found that carriers of the BCL2rs4940571G risk allele had increased absolute numbers of FOXP3+Helios+ Treg cells, which are involved in suppressing the antitumor activity of multiple immune cell types, including effector and Treg cells, B cells, natural killer cells, natural killer T cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells. Several suppressive characteristics have been described for these Treg cells, including increased production of anti-inflammatory cytokines; enhanced release of perforins and granzymes; high expression of programmed cell death protein 1, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4, and lymphocyte-activation gene 3; and interference in metabolism through IL-2 deprivation.66,67 Furthermore, we observed that carriers of the BCL2rs4940571G allele had decreased circulating concentrations of IFN-γ, which is a cytokine that activates the function of macrophages and cytotoxic T cells, and is also involved in modulating resistance to apoptosis68 and CLL survival,68,69 as well as the response to drugs used to treat patients with CLL.70 In addition, we found that carriers of the BCL2rs1026825G risk allele had increased numbers of CD4+CD25+CD127low Treg cells, which increased with age71 and had specific regulatory and proliferative function in humans.72 Although none of these functional results remained significant after correction for multiple testing, in silico functional analysis also showed that BCL2rs12457371 and BCL2rs1026825 SNPs maps among histone marks, QTLs, and influence chromatin states in blood cells, which were proposed to play a role in the development of CLL.73,74 Additionally, we found that the BCL2rs1026825 SNP was strongly associated with a chromatin accessibility QT locus in lymphocytes, suggesting that this marker regulates the accessibility of transcription factors to chromatin and transcription. These results, along with those showing that the BCL2rs4940571 SNP alters the binding sites for B double prime 1, a transcription factor involved in RNA polymerase III transcription, cancer development, and tumor progression,75 suggest that these SNPs might modulate the risk of CLL through immune- and nonimmune-related mechanisms.

This study also validated previously reported associations between SNPs within the BCL2, fas cell surface death receptor (FAS), and BAK1 loci and CLL risk. Although none of these SNPs were associated with autophagy flux levels, our functional analyses revealed that healthy carriers of the FASrs1926194A risk allele had increased circulating concentrations of TRAIL and CD40. In line with these findings, it has been reported that TRAIL acts with FAS-ligand to synergistically induce apoptosis of CD40-activated CLL B cells,76 and TRAIL also interacts also with “decoy” receptors (TRAIL-R3 and R4) to protect cells from apoptosis.77 Furthermore, other authors have demonstrated that CLL cells are resistant to TRAIL-induced apoptosis78 and that CD40 is involved in instructing CLL cells to attract monocytes via the C-C chemokine receptor type 2 pathway.79 In addition, the FASrs1926194 SNP was reported to be strongly associated with ACTA2 mRNA expression levels in the whole blood and lymphocytes, which is a known susceptibility locus for CLL involved in cell migration80,81 and cancer development.81 These findings suggest that the FASrs1926194 SNP might modulate CLL risk through the induction of an antiapoptotic effect of TRAIL on CLL cells and monocyte/macrophage recruitment, as well as by promoting cell migration and proliferation. In line with this hypothesis, we also found that carriers of the FASrs1926194A allele had increased circulating concentrations of chemokine ligand 20, a chemokine produced by monocytes and macrophages and involved in promoting cell migration, proliferation, metastasis, and cancer progression.82,83

Although it was tempting to speculate that autophagy might be the mechanism affecting the risk of developing CLL, the markers in the CDKN2A, BCL2, FAS, and BAK1 genes did not associate with autophagy flux levels. This confirms that these genes might not influence disease onset through the control of this mechanism, but rather through the modulation of multiple immunological and nonimmunological mechanisms, implicating specific immune cells, cytokines, and multiple transcription factors.

Finally, in this study, we evaluated whether autophagy-related variants were associated with OS and TTFT in the CRuCIAL cohort. Although we found a modest association between the TFEBrs6910366 and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs and longer OS and shorter TTFT, respectively, these associations did not remain significant after correction for multiple comparisons. Therefore, we concluded that autophagy-related SNPs do not have a significant effect on patient survival or disease progression. Although a previous study suggested that a promoter variant within BCL2 was weakly associated with disease progression,84 these results could not be confirmed by others,85 which reinforced the idea of a null effect of autophagy variants on OS and disease progression.86

The major strengths of our study are the comprehensive analysis of inherited genetic variation in 234 autophagy-related genes reported in the autophagy database and the inclusion of 4 large independent European populations, including 5472 CLL cases and 726 465 healthy controls. Additionally, we analyzed the impact of autophagy-related SNPs on the modulation of blood cell counts, serum and plasma metabolites, and host immune responses in a large cohort of healthy donors from the HFGP. We had >80% power (log-additive model) to detect an OR of 1.15 at α = 2.63 × 10−5 (multiple testing threshold) for a polymorphism with a minor allele frequency of at least 0.25. A weakness of this study was its multicentric nature, which placed inevitable drawbacks, such as the impossibility of collecting clinical history for a significant proportion of the patients analyzed. Finally, because all study participants included in this analysis were of European ancestry, we could not determine the impact of autophagy variants on CLL risk in other ethnic groups. Additional studies using other populations are warranted to confirm the results of this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study identified, to our knowledge, for the first time, CDKN2A as a new susceptibility locus for CLL. Importantly, this study also identified new susceptibility variants for BCL2 and confirmed the association of previously reported variants within BCL2, FAS, and BAK1 with CLL risk. Our functional data suggest that the effect of CDKN2A, BCL2, and FAS loci on CLL risk is mediated by genetic variants that regulate CDKN2A and ACTA2 mRNA expression levels and shape host immune responses. Finally, this study also revealed that autophagy-related variants do not seem to play a role in disease progression or patient survival. These latter findings must be confirmed in independent populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all study participants who agreed to participate in the study.

This work has been funded by The Instituto de Salud Carlos III and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER; Madrid, Spain; PI17/02256 and PI20/01845 [J.S.]; PI11/02213 and PI15/00966 [R.M.-G.]), Consejería de Transformación Económica, Industria, Conocimiento y Universidades and FEDER (PY20/01282 [J.S.]), Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute (grant no. FIJC1100 [R.M.-G.]), and the voluntary economical contribution of patients. This research was also supported by the EU fund, PNRR CN3 Terapia Genica-Spoke 2 (project no. CN00000041) and Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie Modena Organizzazione di Volontariato (M.L.). The University of Utah was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants R01 CA134674 and P30 CA042014-29S9 (N.J.C.). Data collection in Utah was supported by the Utah Population Database (UPDB) and the Utah Cancer Registry (UCR). The UPDB is supported by the Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) (including Huntsman Cancer Foundation), The University of Utah, and NCI grant P30 CA2014. The UCR was additionally funded by the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, HHSN261201800016I, and the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NU58DP007131). The University of Utah thanks all study participants and the ascertainment, laboratory, biobanking, and research informatics teams at the HCI. The Interlymph Data Coordinating Center was supported by the NCI grant U01CA257679.

Authors identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization are alone responsible for the views expressed in this article, and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policies, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization.

Authorship

Contribution: J.S. designed and coordinated this study, performed the statistical analysis of the functional data, and obtained funding and performed data quality control together with A.J.C.-S., who performed genetic association analyses; A.J.C.-S., J.M.S.-M., P.G.-M., E.C.-C., and E.M.P., and J.S. were involved in the generation of genetic data from the CRuCIAL cohort and drafted the manuscript; M.Á.L.-N., R.T.H., and Y.L. provided functional raw data from the Human Functional Genomic Project cohort; J.J.R.-S., F.J.R.-Z., R.C., A.P., Y.B., A.J., S.L., B.E., R.M., M.Á.L.-N., S.R.-C., C.G.-O., T.-H.C.-L., V.M., F.J., R.M.-G., M.C.-F., B.S.-M., I.G., M.G.-Á., N.J.C., T.D.-S., J.K., A.D.N., M.L., M.A., D.C., S.d.S., R.M., A.C.-G., F.C., M.I., J.M., D.C., S.I.B., and S.L.S. provided genetic data; B.S.-M. and P.L. provided autophagy flux data; and all authors contributed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Juan Sainz, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Granada, Avda Fuente Nueva, s/n, 18071 Granada, Spain; email: jsainz@ugr.es.

References

Author notes

Genetic data generated and analyzed during this study are stored on secure local File Transfer Protocol (FTP) servers at the Centre for Genomics and Oncological Research, Granada, Spain, research center and are available, upon reasonable request, from the corresponding author, Juan Sainz (jsainz@ugr.es). The functional data used in this project were meticulously catalogued and archived in the Biobanking and BioMolecular resources Research Infrastructure – Netherlands (BBMRI-NL) data infrastructure (https://hfgp.bbmri.nl/) using the Molgenis open-source platform for scientific data. This allows flexible data querying and download, including sufficiently rich metadata and interfaces for machine processing (R statistics, Representational State Transfer Application Programming Interface[REST API]), and Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) principles to optimize the ability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Functional impact of the BCL2rs1026825 and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs. Association of the BCL2rs1026825 and BCL2rs4940571 SNPs with absolute numbers of specific subsets of T cells and regulatory T cells, circulating concentrations of inflammatory proteins (IFN-γ and IL-2 receptor subunit β) and IL-6 levels after stimulation of PBMCs with Pam3Cys. NS, nonsignificant; Pam3Cys, N-palmitoyl-S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(R)-propyl]-cysteine.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/23/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025017345/2/m_blooda_adv-2025-017345-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1769545761&Signature=KUtcgrtBSbHCze7mgHRPC4ROBI4-XRY7VFtzFW7BVzuaWP2h-YV03U702KsgG7x18SBPigMxqIlGfuKUHtNyqaHlc8JatHCCqF~eXmQk7u5OuMpPfLcl2uQ2bf6iZXWcoKzLwFRJgcCwYSLXr7Pie10hPJYFskd1CiD4K2zFNhEBJaumejWJdISx35n1FfiHqGqF~8gzq83Uo3uQ-efxZ7gzxCyEQFUiA~a~p8WBI-OEt7K2c-awWcxZ9q0Nrl8X8C0pzmQwk7hgDgszcJd3n9mQSrHJZcAr7Utmn2FdRRZYiTaedSBDcUbtrdzdiZ3NUcFiV60q5BcodjX-5biUbQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)