TO THE EDITOR:

Despite therapeutic advances, multiple myeloma (MM) remains incurable, with relapse associated with progressive immune dysfunction.1 Although T-cell exhaustion in MM is well established, innate immune remodeling during disease progression remains largely unexplored.2 Given the dependence of MM therapies on immune cytotoxicity, elucidating mechanisms of innate immune escape is essential.3

Natural killer (NK) cells are crucial in immune surveillance, directly killing malignant plasma cells and mediating antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.4,5 Single-cell RNA-sequencing revealed an altered MM tumor microenvironment (TME), where dysfunctional NK cells, marked by reduced CD16 expression and degranulation, impair neoplastic clearance and enable immune escape.6-8

Beyond NK cells, other innate lymphoid cell (ILC) subsets regulate tissue homeostasis and immune responses and are increasingly recognized as key players in cancer immunology.9 Although ILCs are well-studied in inflammation, their role in MM remains unknown, with most research being centered on the earlier stage, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS).10 Hence ILCs, especially ILC1 and ILC2, likely shape the TME and modulate immunotherapy efficacy.11,12

Furthermore, by analyzing NK cells and ILCs freshly isolated from peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) of healthy donors and patients across all disease stages, from MGUS through smoldering MM (SMM) to newly diagnosed MM (NDMM), our study captures immune alterations associated with myeloma progression (supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

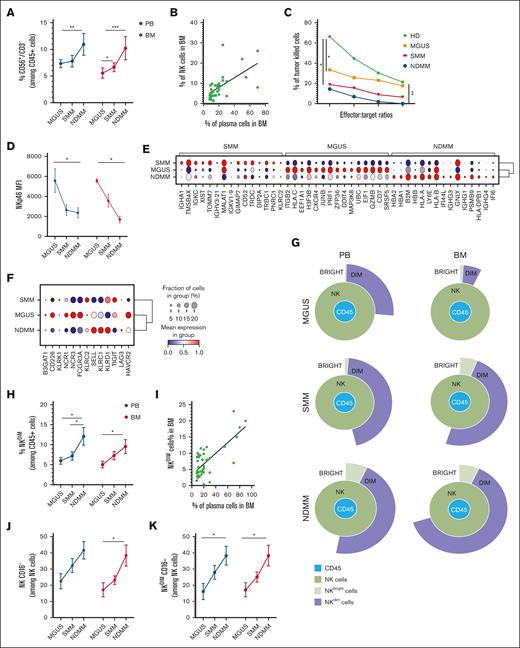

We observed that NK-cell frequency progressively increased from MGUS to NDMM in both PB and BM (Figure 1A). BM-NK-cell percentage correlated with tumor burden (Figure 1B). Despite this expansion, NK cells exhibited functional impairment, displaying significantly reduced cytotoxic activity (Figure 1C). NK cells isolated from MGUS already showed signs of impairment that were marked in SMM and NDMM individuals. This impairment was linked to a downregulation of critical activating receptors, NKp46 and NKp44, essential for effective NK-cell–mediated tumor elimination and upregulation of CD94 inhibitory receptor (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 1A). These results obtained on fresh ex vivo samples were confirmed by analyzing a public single-cell RNA-sequencing data set.6 Clustering identified a distinct NK-cell population characterized by specific-gene expression across all MM stages, with cluster 2 (C2) enriched in NK-cell–specific markers (supplemental Figure 1B-D). Focusing on the top 15 genes in C2, MGUS was characterized by high expression of cytotoxic molecules like granzyme B and perforin compared to SMM and NDMM (Figure 1E), which was consistent with cytotoxic activity (Figure 1C). Moreover, the expression of transcripts encoding activating NK-cell receptors decreased during MM progression. We found a higher expression of transcripts encoding inhibitory receptors in SMM and NDMM compared to MGUS (Figure 1F). These findings suggest that although NK cells expand with tumor burden, their capacity to eliminate MM cells may become markedly impaired.

NK cells in MM progression. (A) The plot represents the percentages of NK cells (CD56+CD3–) among CD45+ cells expressed as median values ± standard error of the mean (SEM) in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages (MGUS, SMM, and NDMM). A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005, and ∗∗∗P < .001. (B) Correlation between the percentage of total NK cells in BM of patients with MM (at different stages) and the percentage of plasma cells in the BM. Linear regression of correlation, Pearson r2 = 0.38. (C) Cytotoxic activity of NK cells isolated from PB of patients with MM (n = 3 MGUS = orange, n = 5 SMM = red, n = 3 NDMM = blue). NK cells from the PB of HD were used as control. Data are expressed as percentages of killed cells at different effector:target ratios. An unpaired t test was performed, comparing the values at the 10:1 ratio, ∗P < .05 and ∗∗P < .005. (D) MFI of NKp46 ± SEM expressed on total NK cells in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages (MGUS, SMM, and NDMM). A 2-way analysis of variance, Sidak multiple comparisons test was performed, ∗P < .05. (E) Dot plot of the 15 most distinguishing genes expressed in NK cells, stratified in the 3 stages of patients with MM (SMM, MGUS, and NDMM). Gene expression was analyzed using the 2-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni adjustment. Ribosomal genes and mitochondrial genes were removed for clarity. The color indicates the mean gene expression levels. (F) Dot plot of selected NK-cell genes encoding for inhibitory and activating receptors, stratified in the 3 stages of patients with MM (SMM, MGUS, and NDMM). The color indicates the mean gene expression levels. (G) Representative Sunburst view of the NK-cell subsets (green circle) among leukocytes (CD45+ cells, blue circle). NKdim (purple circle) and NKbright (light green circle) among the different MM stages in PB (left) and BM (right), analyzed with Cytobank Premium. (H) Percentages of NKdim (CD56dim) cells (among CD45+ cells) in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages. A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05. (I) Correlation between the percentage of NKdim cells in the BM of patients with MM (at different stages) and the percentage of MM plasma cells (infiltrate). Linear regression of correlation, Pearson r2 = 0.52. (J) Frequency of total CD56+CD16– cells among total NK cells in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages. A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05. (K) Frequency of CD56dimCD16– cells among NKdim cells in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages. A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05. HD, healthy donor; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

NK cells in MM progression. (A) The plot represents the percentages of NK cells (CD56+CD3–) among CD45+ cells expressed as median values ± standard error of the mean (SEM) in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages (MGUS, SMM, and NDMM). A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .005, and ∗∗∗P < .001. (B) Correlation between the percentage of total NK cells in BM of patients with MM (at different stages) and the percentage of plasma cells in the BM. Linear regression of correlation, Pearson r2 = 0.38. (C) Cytotoxic activity of NK cells isolated from PB of patients with MM (n = 3 MGUS = orange, n = 5 SMM = red, n = 3 NDMM = blue). NK cells from the PB of HD were used as control. Data are expressed as percentages of killed cells at different effector:target ratios. An unpaired t test was performed, comparing the values at the 10:1 ratio, ∗P < .05 and ∗∗P < .005. (D) MFI of NKp46 ± SEM expressed on total NK cells in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages (MGUS, SMM, and NDMM). A 2-way analysis of variance, Sidak multiple comparisons test was performed, ∗P < .05. (E) Dot plot of the 15 most distinguishing genes expressed in NK cells, stratified in the 3 stages of patients with MM (SMM, MGUS, and NDMM). Gene expression was analyzed using the 2-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni adjustment. Ribosomal genes and mitochondrial genes were removed for clarity. The color indicates the mean gene expression levels. (F) Dot plot of selected NK-cell genes encoding for inhibitory and activating receptors, stratified in the 3 stages of patients with MM (SMM, MGUS, and NDMM). The color indicates the mean gene expression levels. (G) Representative Sunburst view of the NK-cell subsets (green circle) among leukocytes (CD45+ cells, blue circle). NKdim (purple circle) and NKbright (light green circle) among the different MM stages in PB (left) and BM (right), analyzed with Cytobank Premium. (H) Percentages of NKdim (CD56dim) cells (among CD45+ cells) in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages. A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05. (I) Correlation between the percentage of NKdim cells in the BM of patients with MM (at different stages) and the percentage of MM plasma cells (infiltrate). Linear regression of correlation, Pearson r2 = 0.52. (J) Frequency of total CD56+CD16– cells among total NK cells in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages. A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05. (K) Frequency of CD56dimCD16– cells among NKdim cells in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages. A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05. HD, healthy donor; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Likewise, phenotypic analysis revealed that the CD56dim NK cells, typically the most cytotoxic, significantly increased from MGUS to NDMM, and in particular, the BM CD56dim NK cells correlate with neoplastic infiltration (Figure 1G-I). However, this shift was accompanied by an accumulation of CD16– NK cells (Figure 1J). CD16 expression is critical for NK-cell engagement with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs); thus, its downregulation affects the efficacy of mAb-mediated therapy (daratumumab and isatuximab).7 The increasing frequency of CD56dimCD16– NK cells in NDMM suggests a transition toward an impaired phenotype, leading to reduced engagement in immune-mediated tumor shrinkage (Figure 1K). These findings highlight that NK-cell dysfunction, alongside T-cell impairment, drives immune escape in MM. Given the broad use of anti-CD38 antibodies in MM, preserving or restoring CD16 expression may markedly enhance patient outcomes.

Beyond NK cells, MM profoundly alters the composition and function of the other ILC subsets, further shaping an immunosuppressive TME.13 Following the guidelines for ILC identification,14 we evaluated all ILC subsets in healthy donor (supplemental Figure 2A-B) and in patients during MM progression in both PB and BM (Figure 2A). We observed a slight reduction in total ILC frequency in BM during the progression of MM (Figure 2B-C). Within ILCs (identified as Lin–/CD127+), a significant decrease in ILC1 was detected (Figure 2D). ILC1 shares functional similarities with NKs and mediates type 1 immune responses that prompt cancer clearance. Their loss suggests an early suppression of innate immunity, potentially allowing MM cells to evade immune recognition.

ILCs in MM progression. (A) Gating strategy for ILC identification and transcription factor expression in different ILC subsets present in BM and PB. (B) The plot represents the percentages of ILCs (Lin–/CD127+) expressed as median values ± SEM in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages (MGUS, SMM, and NDMM). (C) Representative Sunburst view of the ILC subsets among leukocytes (CD45+ cells, dark orange circle). Lin–CD127+ cells (orange circle), ILC1 (light orange), ILC2 (green), and ILC3 (light green) among the different MM stages in PB (left) and BM (right), analyzed with Cytobank Premium. (D-F) Frequency of ILC1 (D), ILC2 (E), and ILC2 CRTH2+CD117– (F) in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages. A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05 and ∗∗P < .005.

ILCs in MM progression. (A) Gating strategy for ILC identification and transcription factor expression in different ILC subsets present in BM and PB. (B) The plot represents the percentages of ILCs (Lin–/CD127+) expressed as median values ± SEM in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages (MGUS, SMM, and NDMM). (C) Representative Sunburst view of the ILC subsets among leukocytes (CD45+ cells, dark orange circle). Lin–CD127+ cells (orange circle), ILC1 (light orange), ILC2 (green), and ILC3 (light green) among the different MM stages in PB (left) and BM (right), analyzed with Cytobank Premium. (D-F) Frequency of ILC1 (D), ILC2 (E), and ILC2 CRTH2+CD117– (F) in PB and BM of patients with MM among the different stages. A Mann-Whitney t test was performed; ∗P < .05 and ∗∗P < .005.

In line with a previous study focused on ILC2 subset in the BM of NDMM,15 we observed an ILC2 expansion in both PB and BM during MM progression (Figure 2E). ILC2 has been implicated in tissue remodeling and immune regulation in other cancers, often playing a protumorigenic role by supporting tumor growth and immune evasion.4,12,16 Its expansion in MM suggests that ILC2 may contribute to an immunosuppressive TME, in parallel, promoting tumor persistence and therapy resistance. We observed an increase in CRTH2+CD117– ILC2 (Figure 2F), a subset linked to type 2 cytokine production. This subset has been implicated in tumor-promoting functions in solid cancers, including immunosuppression, eosinophil recruitment, and tissue remodeling.16 In MM, this population may foster a protumorigenic microenvironment by suppressing type-1 immunity, supporting stromal survival, and disrupting BM homeostasis. Although ILC1 depletion removes a key interferon-γ source, the expansion of CRTH2+CD117– ILC2 suggests a shift toward immune suppression and cancer progression (Figure 2F).

Notably, ILC3 exhibited a biphasic trend in BM, increasing in SMM before declining in NDMM (supplemental Figure 2C).

These findings suggest that NK cells and ILC alterations reshape innate immunity, fueling MM persistence.

Cytokine profiling revealed mirrored dynamics in PB and BM during MM progression, involving C-reactive protein, platelet factor 4, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and chemokine (CC motif) ligand 5 (supplemental Figure 3A). These factors contribute to chronic inflammation, impaired NK-cell and ILC function, altered cell trafficking and adhesion, and immune modulation, collectively shaping a TME that supports disease progression.6 In addition, we detected interleukin-17E and Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin (TSLP) increased in NDMM patients, paralleling the expansion of the ILC2 (supplemental Figure 3B).

In light of these cytokine shifts, maintaining ILC1 function through interleukin-15 agonists could help counterbalance immune suppression and reinforce innate defenses against MM progression.17,18

On top of that, evaluating NK cells and ILC dysregulation in MM unveils key biomarkers that can refine risk stratification and inform tailored strategies.19,20 Indeed, loss of CD16 expression in NK cells could predict resistance to mAb-based therapies, whereas ILC1 depletion in BM may correlate with poor prognosis and advanced disease.4,7,21,22 Conversely, ILC2 expansion in PB and BM could indicate an immunosuppressive TME, allowing the identification of patients who may benefit from novel immunomodulatory interventions.23

This study reveals a previously unrecognized axis of immune dysregulation in MM, where NK-cell exhaustion and ILC reprogramming may drive immune escape. The loss of NK-cell cytotoxicity, CD16 downregulation, and ILC1 reduction, coupled with ILC2 expansion, likely establish an immunosuppressive TME that promotes MM progression21 and drug resistance.24 These findings endorse immune strategies including NK-cell reactivation, CD16 augmentation, and ILC-targeted interventions as promising avenues to enhance MM outcomes.25 Amid adoptive cell-based immunotherapy, our findings may guide the development of NK-cell–based therapies, using either unrelated donor mature–derived CD16+ NK cells or chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) NK cells. Notably, such CAR NK cells could act both via CAR and via CD16 in cooperation with therapeutic antibodies.

Collectively, integrating biomarker-guided stratification with NK- and ILC-directed approaches may refine treatment strategies in MM, improve patient outcomes, and address innate immune dysfunction as a driver of therapeutic resistance.

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki, the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, applicable International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable local laws and regulations. This study was approved by the “Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico di Bari, Italy Ethics Committee (Del no. 394, approved on 12 April 2024 and Del no. 1448, approved on 25 November 2024). All procedures involving human participants were conducted following the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients before they participated in the study. All participants provided written informed consent for the publication of anonymized data derived from this study.

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by the “Fondo per il Programma Nazionale di Ricerca e Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale—PRIN” (project no. 2022ZKKWLW to A.G.S.), by a grant from “Società Italiana di Medicina Interna” 2023 Research Award (CAMEL) to A.G.S., and by the Italian network of excellence for advanced diagnosis (INNOVA), Ministero della Salute code PNC-E3-2022-23683266 PNC-HLS-DA to A.G.S. and V.D. This research was also cofunded by the Complementary National Plan PNC-I.1 “Research initiatives for innovative technologies and pathways in the health and welfare sector” D.D. 931 of 06/06/2022, DARE—DigitAl lifelong pRevEntion initiative, code PNC0000002, CUP B53C22006420001 to R.R. Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC): IG 2022 – ID. 27065 project (P.V.), AIRC 2018 5 × 1000 – ID. 21147 project (L.M.). This work was also supported by the Italian Ministry of Health with “Current Research Funds”. M.T.B. is the recipient of a fellowship awarded by AIRC.

Contribution: A.G.S., P.V., and N.T. conceptualized the study; A.G.S., A. Argentiero, L.M., P.V., and N.T. supervised the project; M.T.B., A.G.S., V.D., P.V., and N.T. designed the research; M.T.B., A.S., V.D., L.D.M., A.G.S., A. Andriano, P.V., and N.T. performed data analysis; S.F. performed bioinformatic analysis; M.T.B., A.G.S., L.Q., V.D., S.F., P.V., and N.T. wrote the manuscript; M.T.B., A.S., V.D., and L.D.M. conducted experiments; M.T.B., A.G.S., A. Argentiero., V.D., P.V., and N.T. analyzed and interpreted the data; A.G.S., A. Argentiero, L.Q., L.M., V.D., R.R., P.V., and N.T. supervised the study and secured funding; A.G.S., A. Andriano, A.M., and R.R. provided clinical expertise, obtained informed consent, and enrolled the patients; and all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.G.S. has received speaker honoraria from Sanofi, Amgen, and AstraZeneca; has participated in advisory boards for Pfizer and Menarini; and received travel support for educational purposes from Janssen-Cilag. R.R. received honoraria and participated in advisory boards for Pfizer, Sanofi, Bristol Myers Squibb-Celgene, Octapharma, Takeda, Janssen-Cilag, AstraZeneca, Menarini, CSL-Behring, and Amgen. Their potential conflicts of interest do not imply bias or influence on the authors’ opinions or actions. The authors recognize the importance of transparency in the scientific field and are committed to upholding their integrity and maintaining trust in them within the scientific community. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Antonio G. Solimando, Guido Baccelli Unit of Internal Medicine, Department of Precision and Regenerative Medicine and Ionian Area, School of Medicine, University of Bari Aldo Moro, P.zza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124, Bari, Italy; email: antonio.solimando@uniba.it.

References

Author notes

M.T.B. and A.G.S. are joint first authors.

P.V. and N.T. are joint senior authors.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, Antonio Giovanni Solimando (antonio.solimando@uniba.it).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.