Key Points

A novel short TNS1 isoform (eTNS1) with a unique primate-specific start exon 1E increases late in terminal erythroid differentiation.

CRISPR-associated protein 9 deletion of eTNS1 impairs F-actin assembly in orthochromatic erythroblasts and reduces enucleation efficiency.

Visual Abstract

Mammalian red blood cells are generated via a terminal erythroid differentiation pathway culminating in cell polarization and enucleation. Actin filament (F-actin) polymerization is critical for enucleation, but the underlying molecular regulatory mechanisms remain poorly understood. We used publicly available RNA sequencing and proteomic data sets to mine for actin-regulatory factors differentially expressed during human erythroid differentiation and discovered that a focal adhesion (FA) protein, tensin-1 (TNS1), dramatically increases in expression late in differentiation. Remarkably, we found that differentiating human CD34+ cells express a novel truncated form of TNS1 (erythroid TNS1 [eTNS1]; Mr ∼125 kDa) missing the N-terminal half of the protein containing the actin-binding domain, due to an internal messenger RNA translation start site resulting in a unique exon 1E. The region upstream of eTNS1 has features of an active erythroid promoter, demonstrating increasing chromatin accessibility during terminal differentiation, paralleling increasing gene expression. Sequence comparisons across species indicate that eTNS1 is expressed in humans and nonhuman primates, but not in zebrafish, mice, or other rodents. Confocal microscopy showed that eTNS1 localized to the cytoplasm during terminal erythroid differentiation but, surprisingly, did not appear to form focal adhesions nor to colocalize with F-actin. Knockout of eTNS1 did not affect terminal differentiation or assembly of the spectrin membrane skeleton but led to reduced F-actin assembly and abnormal organization in polarized and enucleating erythroblasts, resulting in impaired enucleation efficiency. We conclude that eTNS1 is a novel regulator of F-actin during human erythroid terminal differentiation that is required for efficient enucleation.

Introduction

Erythropoiesis in mammals is a complex process that begins with hematopoietic stem cell commitment to the erythroid lineage, proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells, followed by terminal differentiation, with gradually decreasing cell and nuclear size, cell cycle exit, and enucleation to yield a reticulocyte and a pyrenocyte.1-5 During terminal differentiation, erythroblasts undergo membrane remodeling, mitochondria and organelle loss, as well as cytoskeletal reorganization to form a 2-dimensional spectrin-based membrane skeleton comprised α1,β1-spectrin and short actin filaments (F-actin) along with other components.6-8

Efficient enucleation requires the actin cytoskeleton and microtubules, with microtubule assembly promoting nuclear polarization, whereas F-actin assembly and nonmuscle myosin IIB (NMIIB) contractility are essential for nuclear extrusion.9-14 In mammalian erythroblasts, immediately before nuclear expulsion, F-actin and NMIIB assemble into a prominent cytoplasmic structure at the rear of the nucleus, termed the enucleosome, which is proposed to provide forces to drive nuclear extrusion (Figure 1A).14,15 In mouse, but not human erythroblasts, F-actin and NMIIB also assemble into a ring-like structure surrounding the cellular constriction site, termed the contractile F-actin ring, which may also provide forces for extrusion.11,12,16

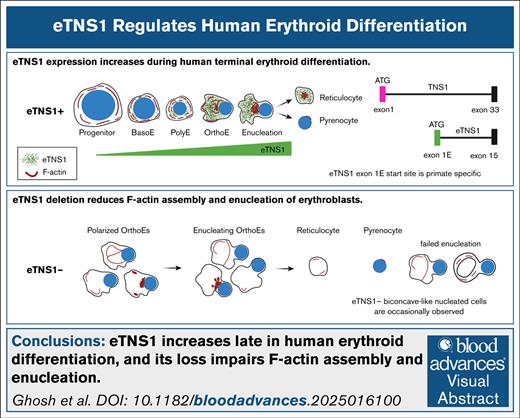

Database mining of ABPs and actin NFs reveals increased TNS1 expression during human terminal erythroid differentiation. (A, top) Schematic of F-actin reorganization (red) into the enucleosome, GPA sorting to the reticulocyte (green), and nuclear expulsion (blue) during human erythroblast enucleation. Figure created with give the Biorender.com. (Diaz, D. 2025, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/64b97cb2f83e095a50810cbb) (A, middle) Maximum intensity projection of Airyscan Z-stacks of human CD34+ cells before and during enucleation stained for GPA (green), F-actin (phalloidin; red), and nuclei (Hoechst; blue). (A, bottom) F-actin staining in grayscale shows the formation of the enucleosome at the rear of the nucleus. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) Flowchart representing the data-mining strategy for 135 ABP and actin NFs to identify mRNAs and proteins that are upregulated during terminal erythroid differentiation of CD34+ cells. Graphs showing fold-change in expression of (C) 97 RNA-seq and (D) 49 proteomics hits during terminal erythroid differentiation. Values were plotted on a linear scale (converted from log2-fold change) and normalized to their respective expression level at the proerythroblast stage.

Database mining of ABPs and actin NFs reveals increased TNS1 expression during human terminal erythroid differentiation. (A, top) Schematic of F-actin reorganization (red) into the enucleosome, GPA sorting to the reticulocyte (green), and nuclear expulsion (blue) during human erythroblast enucleation. Figure created with give the Biorender.com. (Diaz, D. 2025, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/64b97cb2f83e095a50810cbb) (A, middle) Maximum intensity projection of Airyscan Z-stacks of human CD34+ cells before and during enucleation stained for GPA (green), F-actin (phalloidin; red), and nuclei (Hoechst; blue). (A, bottom) F-actin staining in grayscale shows the formation of the enucleosome at the rear of the nucleus. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) Flowchart representing the data-mining strategy for 135 ABP and actin NFs to identify mRNAs and proteins that are upregulated during terminal erythroid differentiation of CD34+ cells. Graphs showing fold-change in expression of (C) 97 RNA-seq and (D) 49 proteomics hits during terminal erythroid differentiation. Values were plotted on a linear scale (converted from log2-fold change) and normalized to their respective expression level at the proerythroblast stage.

To investigate a role for novel actin-binding proteins (ABPs) during terminal erythroid differentiation and enucleation, we adopted a data-mining approach to identify ABPs and actin nucleation factors (NFs) within transcriptomics (RNA sequencing [RNA-seq]) and proteomics liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry data sets for human erythroid differentiation.17,18 We discovered a single actin-binding protein, tensin-1 (TNS1), that was upregulated transcriptionally and translationally late in human terminal erythroid differentiation from CD34+ cells. TNS1 is a ∼220 kDa focal adhesion (FA) molecule involved in cellular adhesion, polarization, migration, proliferation, and invasion.19-21 TNS1 has a FA binding site (FAB-N) containing an actin-binding domain (ABD-I) in the N-terminal region, a centrally located second actin-binding domain (ABD-II); and a C-terminal FA binding site (FAB-C) with Src homology 2 (SH2) and phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domains.20 The multidomain structure allows TNS1 to localize to integrin-mediated FAs22,23 and act as an integrin adapter, linking the extracellular matrix to the actin cytoskeleton and signal transduction through numerous binding partners.20,21,24,25

In human erythroblasts, we discovered a novel short isoform of TNS1 (Mr ∼125 kDa), termed erythroid TNS1 (eTNS1), expressed from an internal start site in a unique exon 1E, present in humans and other primates, but not in rodents. The eTNS1 protein is missing the N-terminal and internal (ABD-I and II) domains but retains the FAB-C domain. Surprisingly, although eTNS1 localizes to the cytoplasm in polarized and enucleating erythroblasts and does not colocalize with F-actin in the enucleosome, loss of eTNS1 nevertheless greatly impairs F-actin assembly and organization into the enucleosome, significantly reducing enucleation efficiency. Together, these observations identify eTNS1 as a novel regulator of F-actin assembly during human terminal erythroid differentiation and indicate that eTNS1 plays a critical role in promoting erythroblast enucleation.

Methods

CD34+ cell culture and erythroid differentiation

CD34+ cells were isolated from human cord blood (STEMCELL Technologies, catalog no. 70008.2), or adult bone marrow (Yale University, Cooperative Center for Excellence in Hematology), expanded and differentiated into erythroid cells using a 3-phase culturing system.26 Terminal erythroid differentiation was evaluated by flow cytometry, Giemsa staining, TaqMan gene expression, and western blotting (supplemental Methods).

Antibodies and reagents

See the supplemental Methods for a table of antibodies and reagents.

Bioinformatics

Human erythroid messenger RNA (mRNA) expression data were from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; GSE53983)27 and (GEO GSE128269).28 Human erythroid assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (ATAC) with sequencing data were from (GEO GSE128269).28 Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing data of GATA-binding factor 1 (GATA1) and T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia 1 (TAL1) occupancy in human erythroid cells were from (GEO GSE70660).29 TNS1 transcripts were from Ensembl Genome assembly (GRCh37.p12).30 Multispecies Multiz alignment and conservation of the TNS1 locus in 100 vertebrates was from the University of California, Santa Cruz Genome Browser database.31,32

CRISPR editing

CD34+ cells were nucleofected using an Amaxa 4D nucleofector with 20 μL of Nucleocuvette Strip with P3 primary cell kit (Lonza, V4XP-3032), as previously described,33 with modifications (supplemental Methods). Cells (0.25 × 106 to 4 × 106) were nucleofected on day 3 of culture with preincubated 52.5 pmol Alt-R Streptococcus pyogenes CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) V3 (Integrated DNA Technologies [IDT]), 1081058) and 30 pmol of either TNS1 Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 CRISPR RNA (crRNA; IDT) (4304-4323 base pairs [bp]: ATCGGAGACCCACACTGTCCCGG) or Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 negative control crRNA no. 1 (IDT, 1079138) annealed to Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 tracrRNA 5 nmol (IDT, 1072532) using program EO100 or DZ100.

Fluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

Cells were collected from CD34+ cultures on different days during erythroid differentiation, placed on a 12-mm fibronectin-coated coverslip, incubated at 37°C for 2 to 3 hours, followed by phosphate-buffered saline wash. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature overnight in the dark, washed in phosphate-buffered saline permeabilized with 0.3% TX-100, and blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin/1% normal goat serum, followed by incubation with primary and secondary antibodies (supplemental Methods). Airyscan Z-stack images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM880 laser scanning confocal microscope (63× oil objective, Numerical Aperture [NA] 1.4) with a 0.17-μm Z-step.

Imaging with ZEISS CD7

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and immunostained as described earlier. Images were acquired with a Zeiss CellDiscoverer 7 (CD7) confocal fluorescence microscope using the plan-Apochromat 50×/1.2 water immersion objective lens. A total of 54 image tiles (375.36 μm × 226.32 μm) were collected and stitched together to form 1 full image (2.07 mm × 1.86 mm), which was analyzed using a custom analysis program to distinguish erythroblasts and reticulocytes (supplemental Methods). The percentage of eTNS1+ and eTNS1− reticulocytes with respect to eTNS1+ and eTNS1− erythroblasts, was calculated as (number of reticulocytes)/(number of reticulocytes + number of erythroblasts) for either eTNS1+ or eTNS1− categories. To measure F-actin intensity of eTNS1+ and eTNS1− erythroblasts, an additional parameter for rhodamine-phalloidin intensity was added to the program.

Results

Database mining for ABPs identifies increased TNS1 during terminal erythroid differentiation

To investigate regulation of F-actin assembly during human erythroblast enucleation, we identified 135 known ABPs and NFs6,34-36 (supplemental Data set 1) and cross-referenced this list with publicly available RNA-seq and proteomic data sets to determine whether any of these ABPs/NFs increased during terminal erythroid differentiation (Figure 1B; supplemental Data set 2).17,18 For comparison, we conducted a similar analysis of 12 ABPs in the red cell membrane skeleton6,8 and 25 red cell transmembrane and membrane-associated proteins7,37 (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Data set 1). The fold-change in expression was plotted on a linear scale (converted from log2-fold), normalized to proerythroblast expression for each hit (Figure 1C-D; supplemental Data set 2). We found that TNS1 was highly upregulated at both the transcriptional (40-fold increase) and protein (30-fold increase) level in orthochromatic erythroblasts, compared with proerythroblasts (Figure 1C-D). TNS1 expression increased only in late stages of differentiation and was not enriched in Burst Forming Unit-Erythroid (BFU-E) and Colony Forming Unit-Erythroid (CFU-E) erythroid progenitor cells compared with CD34+ cells (supplemental Figure 2). This dramatic increase in TNS1 expression late in terminal differentiation contrasts with other ABPs and NFs in our data set that either decreased or showed a minimal increase (Figure 1C-D).

TNS1 expression increases during terminal erythroid differentiation

To investigate TNS1 function, we differentiated human cord blood–derived CD34+ cells toward the erythroid lineage using a 3-phase culturing system.26 We confirmed terminal erythroid differentiation using Giemsa staining (supplemental Figure 3) and flow cytometry, which showed decreased CD71 and α4 integrin, along with increased Glycophorin A (GPA) and band 3 (supplemental Figure 4).38 Using DRAQ5 nuclear staining, we found that, on average, ∼20% of cells had enucleated to become reticulocytes by day 14 of culture, and ∼35% had enucleated by day 17 of culture (supplemental Figure 4C).

We assessed TNS1 mRNA expression in erythroid cell cultures by TaqMan gene expression (Figure 2A), using a probe spanning exons 32 to 33 near the 3' end of the human TNS1 gene, coinciding with the PTB domain near the C-terminal end of the TNS1 protein (Figure 3B). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction results confirmed a significant 12-fold increase in TNS1 mRNA expression in day-14 cells, compared with day-7 cells (Figure 2A). Next, we examined TNS1 protein levels by western blot using a polyclonal anti-peptide antibody to amino acids 1326 to 1339 of TNS139 and determined that TNS1 protein increased nearly fivefold from day 7 to day 14 in culture (Figure 2B-C). This trend was also observed in erythroblasts differentiated from adult bone marrow–derived CD34+ cells (supplemental Figure 5A-B). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and western blotting confirmed terminal erythroid differentiation with increased expression of membrane skeleton genes (SPTA1, EPB41) and proteins (α1β1-spectrin, protein 4.1R; Figure 2A-C). Unlike U-118 glioblastoma cells, which express full-length TNS1 (Mr ∼220 kDa), no full-length TNS1 is detected in erythroid cells and, instead, a prominent immunoreactive band at Mr ∼125 kDa is present (Figure 2B-C; supplemental Figure 5A-B). This suggests that human erythroid cells may express a short isoform of TNS1 during late stages of terminal erythroid differentiation.

Expression of TNS1 is upregulated during in vitro human terminal erythroid differentiation. (A) mRNA levels of TNS1, β-actin (ACTB), α1-spectrin (SPTA1), and protein 4.1R (EPB41) in CD34+ cell cultures on days 7, 11, and 14 of differentiation, measured by TaqMan quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Values are mean ± standard deviation [SD] from 5 individual CD34+ cultures. Fold-change in gene expression normalized to day 7 cells. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (B) Representative western blots of TNS1, total actin, protein 4.1R, α1β1-spectrin, and total protein of differentiated CD34+ cells, and human U118 glioblastoma cells; 15 μg protein loaded per lane. Asterisk, full-length TNS1 in U118 cells (Mr ∼220 kDa); red arrow, immunoreactive TNS1 polypeptide in erythroid cells (Mr ∼125 kDa). (C) Quantification of immunoblots normalized to total protein. Band intensities analyzed by ImageJ. Values are mean ± SD from 6 individual CD34+ cultures. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) Maximum intensity projections of Airyscan Z-stacks of cells from day-14 cultures, before and at various stages of enucleation, stained for F-actin (red), TNS1 (magenta), GPA (green), and nuclei (blue). Scale bar, 5 μm. ns, non-significant.

Expression of TNS1 is upregulated during in vitro human terminal erythroid differentiation. (A) mRNA levels of TNS1, β-actin (ACTB), α1-spectrin (SPTA1), and protein 4.1R (EPB41) in CD34+ cell cultures on days 7, 11, and 14 of differentiation, measured by TaqMan quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Values are mean ± standard deviation [SD] from 5 individual CD34+ cultures. Fold-change in gene expression normalized to day 7 cells. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (B) Representative western blots of TNS1, total actin, protein 4.1R, α1β1-spectrin, and total protein of differentiated CD34+ cells, and human U118 glioblastoma cells; 15 μg protein loaded per lane. Asterisk, full-length TNS1 in U118 cells (Mr ∼220 kDa); red arrow, immunoreactive TNS1 polypeptide in erythroid cells (Mr ∼125 kDa). (C) Quantification of immunoblots normalized to total protein. Band intensities analyzed by ImageJ. Values are mean ± SD from 6 individual CD34+ cultures. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) Maximum intensity projections of Airyscan Z-stacks of cells from day-14 cultures, before and at various stages of enucleation, stained for F-actin (red), TNS1 (magenta), GPA (green), and nuclei (blue). Scale bar, 5 μm. ns, non-significant.

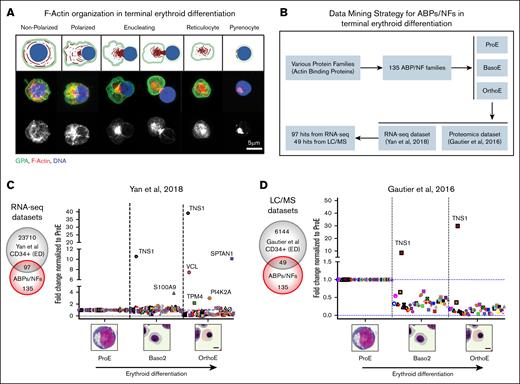

Human erythroblasts express a short isoform of TNS1 (eTNS1). (A) mRNA expression of TNS1 exons during human erythroid differentiation from human stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) through terminal differentiation to orthochromatic erythroblasts. Exons encoding the canonical Ensembl TNS1 mRNA transcript and the eTNS1 mRNA transcript are shown at the bottom, with location of alternate exon 1E containing initiator methionines denoted by arrows. Top, red: mRNA expression, determined by RNA-seq, increases during terminal erythroid differentiation starting at the early basophilic erythroblast stage. Middle, green: peaks of chromatin accessibility, determined by ATAC sequencing, at the promoter and in a putative intron-4 enhancer increase during terminal erythroid differentiation. Bottom, blue: peaks of histone marks and GATA1 and TAL1 transcription factor occupancy, determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing, in Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCa) and proerythroblasts. (B) Comparison of canonical TNS1 gene to eTNS1 short isoform (not to scale), including the unique eTNS1 start exon (1E) highlighted in magenta. Pre-designed TaqMan primer-probe pairs (I-V) were chosen to span the canonical TNS1 cDNA at the specific exon sites shown (Key: TaqMan Exon Probes). sgRNA (yellow triangle) location designed for CRISPR-Cas9 knockout experiments. Figure created with Biorender.com. (Diaz, D. 2025, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/660ab6fdc5f830fa937a2f31) (C) Quantification of mRNA expression (qRT-PCR) calculated as 2(−ΔΔC[T]) for all 5 probes on days 7, 11, and 14 of erythroid cultures. Fold-change in gene expression normalized to average ΔCt value for day-7 cells for each of the 5 probes, using α-tubulin as a housekeeping gene. Values are mean ± SD from 3 individual erythroid cultures. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) Representative western blot for eTNS1, HA, total actin, and total protein in MDCK cells (full-length TNS1), CD34+ day-14 cells (eTNS1), untransfected HEK293T cells, and HEK293T cells transfected with an eTNS1-HA plasmid. Schematic in panel B created with BioRender.com. MDCK, Madin-Darby Canine Kidney; UTR, untranslated region.

Human erythroblasts express a short isoform of TNS1 (eTNS1). (A) mRNA expression of TNS1 exons during human erythroid differentiation from human stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) through terminal differentiation to orthochromatic erythroblasts. Exons encoding the canonical Ensembl TNS1 mRNA transcript and the eTNS1 mRNA transcript are shown at the bottom, with location of alternate exon 1E containing initiator methionines denoted by arrows. Top, red: mRNA expression, determined by RNA-seq, increases during terminal erythroid differentiation starting at the early basophilic erythroblast stage. Middle, green: peaks of chromatin accessibility, determined by ATAC sequencing, at the promoter and in a putative intron-4 enhancer increase during terminal erythroid differentiation. Bottom, blue: peaks of histone marks and GATA1 and TAL1 transcription factor occupancy, determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing, in Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCa) and proerythroblasts. (B) Comparison of canonical TNS1 gene to eTNS1 short isoform (not to scale), including the unique eTNS1 start exon (1E) highlighted in magenta. Pre-designed TaqMan primer-probe pairs (I-V) were chosen to span the canonical TNS1 cDNA at the specific exon sites shown (Key: TaqMan Exon Probes). sgRNA (yellow triangle) location designed for CRISPR-Cas9 knockout experiments. Figure created with Biorender.com. (Diaz, D. 2025, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/660ab6fdc5f830fa937a2f31) (C) Quantification of mRNA expression (qRT-PCR) calculated as 2(−ΔΔC[T]) for all 5 probes on days 7, 11, and 14 of erythroid cultures. Fold-change in gene expression normalized to average ΔCt value for day-7 cells for each of the 5 probes, using α-tubulin as a housekeeping gene. Values are mean ± SD from 3 individual erythroid cultures. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) Representative western blot for eTNS1, HA, total actin, and total protein in MDCK cells (full-length TNS1), CD34+ day-14 cells (eTNS1), untransfected HEK293T cells, and HEK293T cells transfected with an eTNS1-HA plasmid. Schematic in panel B created with BioRender.com. MDCK, Madin-Darby Canine Kidney; UTR, untranslated region.

Erythroblasts from day-14 cultures comprise a heterogeneous population, including nonpolarized, polarized, and enucleating cells (supplemental Figure 3). To evaluate TNS1 expression before and during polarization and enucleation, we performed immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy to examine individual erythroblasts. In erythroblasts derived from cord blood or adult bone marrow CD34+ cells, TNS1 staining appeared weak and diffuse in nonpolarized cells, whereas cells with a polarized nucleus showed abundant bright TNS1 puncta in the cytoplasm, increasing in intensity in enucleating cells (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 5C). Surprisingly, TNS1 immunostaining appeared throughout the cytoplasm and was not enriched with F-actin in the enucleosome at the rear of the nucleus in enucleating cells. After nuclear expulsion, bright TNS1 puncta remained in the reticulocyte, with little to no TNS1 detected within the pyrenocyte (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 5C). This indicates that TNS1 protein levels are specifically increased late in terminal erythroid differentiation, particularly in polarized and enucleating cells.

A truncated TNS1 transcript coding for a novel short isoform of TNS1 (eTNS1) is expressed in human erythroid cells

To investigate the origin of the short TNS1 isoform detected in human erythroid cells, we analyzed RNA-seq data sets for stages of terminal erythroid differentiation from cord blood–derived cells with respect to the genomic structure of human TNS1. The canonical human TNS1 mRNA transcript (Ensembl, TNS1-201) contains 33 exons encompassing 10 331 bp encoding a predicted protein of 1735 residues (185 kDa) (Figures 3A-B and 4A). In human erythroid cells, the canonical transcript is absent, and a truncated mRNA transcript of 4292 bp encoded by 15 exons (TNS1-208) initiates from an internal transcription initiation site in a novel exon 1E containing an in-frame initiator methionine, located in intron 17 of the canonical transcript (Figure 3A-B). This transcript encodes a predicted protein of 846 residues (89 kDa). During human erythropoiesis, the truncated transcript is not expressed until early basophilic erythroblasts, increasing through terminal erythroid differentiation to high levels in polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts (Figure 3A). The area upstream of TNS1 erythroid exon 1E contains an active erythroid promoter with trimethylation of lysine 4 on histone H3 (H3K4), H3K27 acetylation, and GATA1 and TAL1 occupancy (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 6A). This promoter also contains an ATAC peak with chromatin accessibility patterns paralleling increasing TNS1 gene expression in terminal erythroid differentiation. In addition, an erythroid enhancer appears to be present in intron 4 of the truncated transcript, indicated by an ATAC peak, enrichment of histone H3K27 acetylation, and occupancy by erythroid transcription factors GATA1 and TAL1 (Figure 3A).40 A similar pattern of ATAC chromatin accessibility is observed in adult blood-derived erythroid cells (supplemental Figure 5D).41

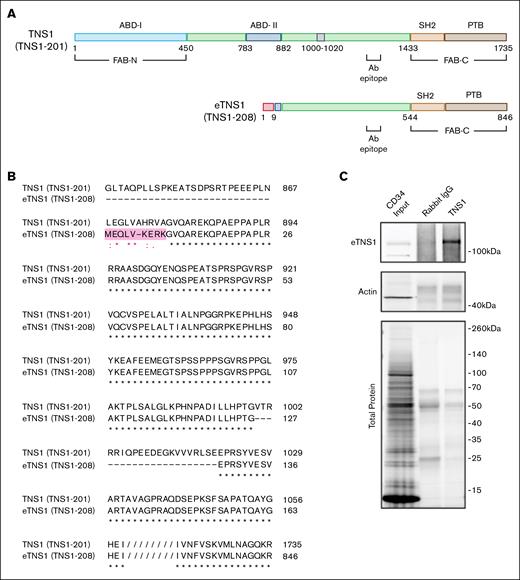

Comparison of protein domains and amino acid alignment of canonical TNS1 and eTNS1. (A) Comparison of canonical TNS1 (TNS1-201) protein domains with eTNS1 (TNS1-208). The amino acids in pink are unique to eTNS1, whereas the 21 amino acids in gray (1000-1020) in canonical TNS1 are missing in eTNS1. The primary antibody epitope is indicated (amino acids 1326-1339 in TNS1). Figure created with BioRender.com. (Diaz, D. 2025, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/660ab6fdc5f830fa937a2f31). (B) Amino acid alignment using UniProt align tool showing amino acids coded for by exon 1E in eTNS1 protein, highlighted in pink. Asterisks, identical residues; colon, residues with strongly similar properties (scoring >0.5 in Gonnet PAM 250 matrix); period, residues with weakly similar properties (scoring <0.5 in Gonnet PAM 250 matrix). (C) Cell lysates from control erythroblasts (day 11) were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an anti-TNS1 antibody. Both the immunoprecipitated material and total cell lysate (input) were analyzed by western blot using antibodies against TNS1 and actin. Schematic in panel A created with BioRender.com.

Comparison of protein domains and amino acid alignment of canonical TNS1 and eTNS1. (A) Comparison of canonical TNS1 (TNS1-201) protein domains with eTNS1 (TNS1-208). The amino acids in pink are unique to eTNS1, whereas the 21 amino acids in gray (1000-1020) in canonical TNS1 are missing in eTNS1. The primary antibody epitope is indicated (amino acids 1326-1339 in TNS1). Figure created with BioRender.com. (Diaz, D. 2025, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/660ab6fdc5f830fa937a2f31). (B) Amino acid alignment using UniProt align tool showing amino acids coded for by exon 1E in eTNS1 protein, highlighted in pink. Asterisks, identical residues; colon, residues with strongly similar properties (scoring >0.5 in Gonnet PAM 250 matrix); period, residues with weakly similar properties (scoring <0.5 in Gonnet PAM 250 matrix). (C) Cell lysates from control erythroblasts (day 11) were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an anti-TNS1 antibody. Both the immunoprecipitated material and total cell lysate (input) were analyzed by western blot using antibodies against TNS1 and actin. Schematic in panel A created with BioRender.com.

This truncated TNS1-208 erythroid transcript (hereby designated eTNS1) is not present in mice or other rodents, chickens, and zebrafish (supplemental Figure 6B). Furthermore, although other Tns1 transcripts are expressed in mouse proerythroblasts, their levels decrease significantly during terminal erythroid differentiation.27 Analysis of species conservation of the DNA sequence at the TNS1-208 locus in the region of the predicted erythroid promoter, reveals that the potential GATA1 and TAL1 occupancy sites, the initiator methionine ATG, and the 5′ donor splice site of exon 1E, are not present in many species (supplemental Figures 6 and 7). Furthermore, this region of the TNS1-208 gene DNA sequence is contained within a long interspersed nuclear element. Thus, the truncated transcript found in human erythroid cells may be primate specific.

Comparison of the canonical TNS1 gene with the eTNS1 short isoform reveals differences in addition to the unique eTNS1 start exon 1E. Exons 20 and 21 in the canonical TNS1 gene are missing in eTNS1 mRNA, and the 3′ untranslated region of eTNS1 is shorter when compared with canonical TNS1 (Figure 3B). To confirm expression of the short eTNS1 transcript in differentiated human erythroblasts, 5 predesigned TaqMan probes were selected for coding exons from the 5′ to 3′ end of full-length TNS1-201, 2 of which also span exons of TNS1-208 (eTNS1; Figure 3B). Only probes IV and V, which span exons in both TNS1-201 and TNS1-208, showed significantly increased mRNA levels at day 14 as compared with day-7 cells from human erythroid cultures (Figure 3C), whereas probes I through III showed considerably less expression, strongly indicating expression of the TNS1-208 transcript in human erythroid cells.

To determine whether the protein translated from the TNS1-208 transcript shares the same molecular weight as the predicted eTNS1 protein, we transfected HEK 293T cells, which lack endogenous TNS1 protein, with a recombinant human TNS1-208 plasmid expressing Hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged eTNS1. HA-eTNS1 transfected cells showed a prominent band at ∼125 kDa, comigrating with the eTNS1 band in CD34+-derived erythroid cell cultures (Figure 3D). Although the eTNS1 apparent molecular weight of ∼125 kDa on sodium dodecyl sulfate gels is greater than the predicted molecular weight of 89 kDa, canonical TNS1 also has an apparent molecular weight (∼220 kDa) greater than the predicted molecular weight of 185 kDa, due to the low electrophoretic mobility of residues 306 to 981 in TNS1’s unstructured domain on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.42 The presence of a portion of this unstructured central region in eTNS1 (Figure 4A), likely contributes to the discrepancy between predicted and observed molecular weights.

Comparison of eTNS1 with full-length TNS1 protein reveals that eTNS1 is missing the N-terminal (ABD-I) and FA targeting domain (FAB-N; Figure 4A).20 The eTNS1 alternative first exon (exon 1E) encodes 9 unique amino acids that diverge from the full-length TNS1 sequence (Figure 4A-B); this alternative exon also eliminates most of the region proposed to contain an internal (ABD-II) in TNS1.20 Following exon 1E, the eTNS1 amino acid sequence corresponds in large part to that of TNS1, with an unstructured domain followed by a FAB-C domain containing SH2 and PTB domains (Figure 4A). To investigate whether eTNS1 interacts directly or indirectly with actin, we immunoprecipitated eTNS1 from erythroblast lysates, followed by western blotting for actin (Figure 4C). The results show that actin is not detected in either the anti-TNS1 or control immunoglobulin G immunoprecipitated samples, suggesting that eTNS1 does not form a stable complex with actin, consistent with absence of TNS1’s ABD in the shorter eTNS1 protein.

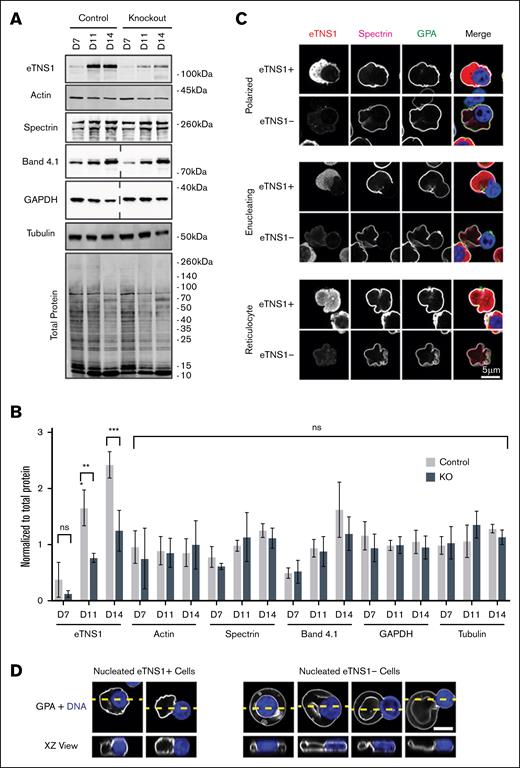

CRISPR-Cas9 KO of eTNS1 does not affect membrane skeleton assembly

To investigate eTNS1 function in terminal erythroid differentiation, we introduced CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes into CD34+ cells on day 3 of in vitro culture,33 using a guide crRNA targeting exon 24 in TNS1-201, coinciding with exon 6 in TNS1-208 (Figure 3B). Although eTNS1-knockout (KO) experiments resulted in a relatively low percentage of insertions and deletions by Sanger sequencing, averaging ∼29% (varying between 20% and 60% over 7 experiments), no changes in global editing efficiency were observed over the course of terminal erythroid differentiation in individual experiments. Western blotting showed that eTNS1 protein levels were reduced by ∼48% on average by day 14 of culture, compared with nontransfected cells, without effect on actin, α1β1-spectrin, protein 4.1R, and α-tubulin (Figure 5A-B). Introduction of CRISPR-Cas9 RNP complexes containing a nontarget crRNA had no effect on eTNS1, actin, α-tubulin, and α1β1-spectrin protein levels (supplemental Figure 8A-B). Flow cytometry of GPA-positive erythroblasts from eTNS1-KO or nontarget control cultures showed the expected increase in CD71low cells late in differentiation (days 14-17; supplemental Figure 9A). In comparison with nontarget controls, an increase in α4 integrin (CD49d)high cells was observed at day 14 in KO cultures, but, by day 17, the difference from nontarget controls was no longer significant (supplemental Figure 9B), suggesting that loss of eTNS1 does not impair terminal differentiation. However, measurements of enucleation efficiency for different eTNS1-KO and nontarget cultures using DRAQ5 nuclear staining were highly variable (supplemental Figure 9C), likely due to the variations in editing efficiency and cellular heterogeneity, leading us to use single-cell analyses in subsequent experiments.

CRISPR-Cas9 KO of eTNS1 in human erythroblasts does not affect assembly of the membrane skeleton or expression of cytoskeletal proteins. (A) Representative western blots of eTNS1, actin, α1,β1-spectrin, protein 4.1R, GAPDH, α-tubulin, and total protein from nontransfected control and eTNS1-KO erythroid cultures; 15 μg protein loaded per lane (dashed lines indicate blots in which lanes were cropped out). (B) Quantification of immunoblots normalized to total protein. Values are mean ± SD from 4 nontransfected controls and 4 KO cultures. ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. (C) Single optical sections of Airyscan Z-stacks of human erythroblasts from day-14 eTNS1-KO cultures, depicting stages of enucleation, stained for eTNS1 (red), β1-spectrin (magenta), GPA (green), and nuclei (Hoechst; blue). Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Single XY optical sections (top panels) of Airyscan Z-stacks of polarized and enucleating eTNS1+ and eTNS1− cells were used to construct XZ side views (bottom panels) of each cell at the location of the yellow dashed line in the top panel. (GPA, white; nucleus, blue). eTNS1− cell shapes appeared to resemble biconcave-like discs, with a rim and dimple in some cases), despite the retention of the nucleus in the cell. Scale bar, 5 μm. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ns, non-significant.

CRISPR-Cas9 KO of eTNS1 in human erythroblasts does not affect assembly of the membrane skeleton or expression of cytoskeletal proteins. (A) Representative western blots of eTNS1, actin, α1,β1-spectrin, protein 4.1R, GAPDH, α-tubulin, and total protein from nontransfected control and eTNS1-KO erythroid cultures; 15 μg protein loaded per lane (dashed lines indicate blots in which lanes were cropped out). (B) Quantification of immunoblots normalized to total protein. Values are mean ± SD from 4 nontransfected controls and 4 KO cultures. ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. (C) Single optical sections of Airyscan Z-stacks of human erythroblasts from day-14 eTNS1-KO cultures, depicting stages of enucleation, stained for eTNS1 (red), β1-spectrin (magenta), GPA (green), and nuclei (Hoechst; blue). Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Single XY optical sections (top panels) of Airyscan Z-stacks of polarized and enucleating eTNS1+ and eTNS1− cells were used to construct XZ side views (bottom panels) of each cell at the location of the yellow dashed line in the top panel. (GPA, white; nucleus, blue). eTNS1− cell shapes appeared to resemble biconcave-like discs, with a rim and dimple in some cases), despite the retention of the nucleus in the cell. Scale bar, 5 μm. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ns, non-significant.

To investigate whether eTNS1 affected membrane skeleton assembly, we used high-resolution Zeiss Airyscan confocal microscopy to visualize eTNS1− and eTNS1+ cells within the same heterogeneous culture. The presence of eTNS1+ cells provided a crucial internal control to compare morphologies of cells without eTNS1 with cells with eTNS1. We observed that α1β1-spectrin assembled normally on the membrane of polarized cells, enucleating cells, and reticulocytes expressing eTNS1 (eTNS1+), or lacking eTNS1 (eTNS1−; Figure 5C). We also noticed that some eTNS1− erythroblasts appeared to be “stuck” in the process of nuclear expulsion, with the incipient reticulocyte assuming a dish-like or biconcave-like shape, reminiscent of a red blood cell (Figure 5D). Single XY optical sections of Z-stacks and orthogonal XZ views show that the eTNS1− incipient reticulocytes have a distinct outer rim, where the nucleus is surrounded by the plasma membrane but protruding from the cell (Figure 5D; supplemental Figure 10). In eTNS1− nucleated cells with a biconcave-like shape, we observe dim F-actin staining at the membrane (supplemental Figure 10). Due to Z stretch in the XZ images, F-actin staining at the membrane is most evident in the XY view of an eTNS1− cell that is fortuitously lying on its side (supplemental Figure 10D, bottom panel). By contrast, incipient reticulocytes of eTNS1+ nucleated erythroblasts are never observed to assume a biconcave-like shape before the nucleus has been expelled. Together with the normal expression and localization of spectrin at the membrane (Figure 5A-C), it appears that the incipient reticulocyte portion of the eTNS1− cell was able to assemble the membrane skeleton and form a biconcave-like shape, without having fully completed nuclear expulsion.

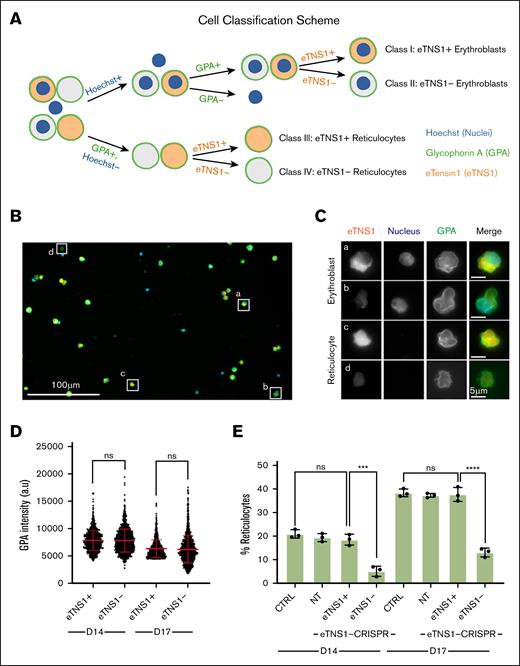

eTNS1 is required for efficient erythroblast enucleation

To determine whether loss of eTNS1 affected erythroblast enucleation efficiency, we employed single-cell high-throughput microscopy using the Zeiss CD7. We classified cells into 4 distinct categories based on presence or absence of nuclei, GPA, and eTNS1: (1) eTNS1+ or (2) eTNS1− erythroblasts, (3) eTNS1+, or (4) eTNS1− reticulocytes (Figure 6A-C). First, we demonstrated that GPA intensity levels did not change in the absence of eTNS1 in differentiating erythroblasts at day 14 or day 17 (Figure 6D), indicating that terminal erythroid differentiation is overall unaffected, in agreement with confocal microscopy and western blots of membrane skeleton proteins (Figure 5A), and flow cytometry of erythroid markers (supplemental Figure 9). However, the percentage of reticulocytes with respect to the total number of GPA-positive erythroblasts and reticulocytes was significantly lower for eTNS1− cells compared with eTNS1+ cells at both day 14 and day 17 in KO cultures (Figure 6E). This same trend was observed when comparing eTNS1− cells from KO cultures with eTNS1+ cells in nontarget and nontransfected control cultures (Figure 6E), leading us to conclude that cells lacking eTNS1 have an enucleation defect that impairs nuclear expulsion.

Single-cell analysis reveals loss of eTNS1 impairs erythroblast enucleation. (A) Schematic of erythroblast classification from eTNS1-KO erythroid cultures into 4 categories based on Hoechst (nuclei; blue), GPA (green), and eTNS1 (orange) staining. Cells were classified as eTNS1+ erythroblasts, eTNS1− erythroblasts, eTNS1+ reticulocytes, and eTNS1− reticulocytes. Figure created with Biorender.com. (Diaz, D. 2025, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/655d7217e036ccb922863c17). (B) Representative single tiled image showing the heterogeneous cell population from an eTNS1 CRISPR KO culture using the Zeiss CD7. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Representative higher magnification images of individual cells in panel A depicting the 4 classes: (a) eTNS1+ erythroblast, (b) eTNS1− erythroblast, (c) eTNS1+ reticulocyte, and (d) eTNS1− reticulocyte. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Quantification of GPA intensity levels of eTNS1+ and eTNS1− cells from day-14 and day-17 eTNS1-KO cultures; 3 to 5 tiled images were taken from a single coverslip for each culture. Plot reflects the mean ± SD of 1500 eTNS1+ and eTNS1− erythroblasts from 3 independent eTNS1-KO cultures. (E) Quantification of eTNS1− and eTNS1+ reticulocytes in control, nontarget, and KO day-14 and day-17 cultures. Percentage reticulocytes calculated by dividing the number of reticulocytes by (the number of reticulocytes plus the number of erythroblasts). Plot reflects mean ± SD of percentage reticulocytes calculated from ∼6000 cells for each experiment. Three independent experiments performed for each condition. ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, non-significant. Schematic in panel A created with BioRender.com.

Single-cell analysis reveals loss of eTNS1 impairs erythroblast enucleation. (A) Schematic of erythroblast classification from eTNS1-KO erythroid cultures into 4 categories based on Hoechst (nuclei; blue), GPA (green), and eTNS1 (orange) staining. Cells were classified as eTNS1+ erythroblasts, eTNS1− erythroblasts, eTNS1+ reticulocytes, and eTNS1− reticulocytes. Figure created with Biorender.com. (Diaz, D. 2025, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/655d7217e036ccb922863c17). (B) Representative single tiled image showing the heterogeneous cell population from an eTNS1 CRISPR KO culture using the Zeiss CD7. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Representative higher magnification images of individual cells in panel A depicting the 4 classes: (a) eTNS1+ erythroblast, (b) eTNS1− erythroblast, (c) eTNS1+ reticulocyte, and (d) eTNS1− reticulocyte. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Quantification of GPA intensity levels of eTNS1+ and eTNS1− cells from day-14 and day-17 eTNS1-KO cultures; 3 to 5 tiled images were taken from a single coverslip for each culture. Plot reflects the mean ± SD of 1500 eTNS1+ and eTNS1− erythroblasts from 3 independent eTNS1-KO cultures. (E) Quantification of eTNS1− and eTNS1+ reticulocytes in control, nontarget, and KO day-14 and day-17 cultures. Percentage reticulocytes calculated by dividing the number of reticulocytes by (the number of reticulocytes plus the number of erythroblasts). Plot reflects mean ± SD of percentage reticulocytes calculated from ∼6000 cells for each experiment. Three independent experiments performed for each condition. ∗∗∗P = .0002; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, non-significant. Schematic in panel A created with BioRender.com.

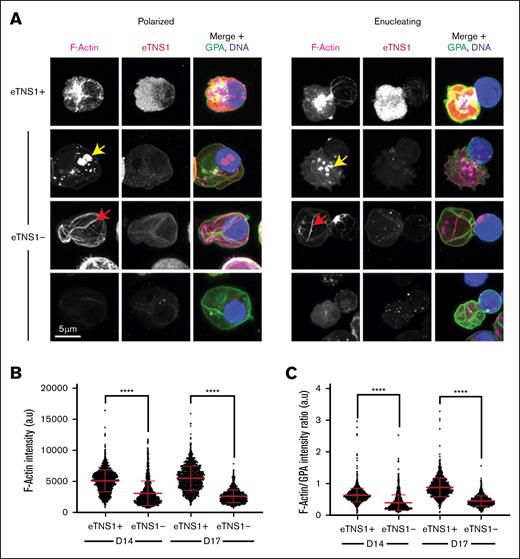

eTNS1 is required for F-actin assembly into the enucleosome

To further investigate the enucleation defect in eTNS1− erythroblasts, we used Airyscan confocal microscopy to examine F-actin organization in eTNS1-KO erythroblasts. Maximum intensity projections of Airyscan Z-stacks showed the F-actin structures in polarized and enucleating eTNS1− cells to be extremely abnormal. Instead of F-actin accumulation into a bright enucleosome at the rear of the nucleus (Figures 1A, 2D, and 7A), eTNS1− erythroblasts had numerous mislocalized F-actin foci located in the cytoplasm or nucleus, irregular F-actin cables extending across the cell, or very little F-actin at all (Figure 7A). Imaging of eTNS1+ and eTNS1− erythroblasts side by side in the same samples demonstrated that the abnormalities in F-actin assembly and organization in the eTNS1− cells were not due to differences in cell preparation, fixation, and staining (supplemental Figure 11). Quantification of F-actin intensity in individual eTNS1+ and eTNS1− polarized and enucleating cells using the Zeiss CD7 confirmed that eTNS1− erythroblasts in both day-14 and day-17 KO cultures have significantly less F-actin than eTNS1+ erythroblasts (Figure 7B). This trend was maintained when F-actin intensity was normalized to GPA intensity (Figure 7C). Together, these single-cell microscopy analyses indicate that eTNS1 is required for the assembly of the F-actin–rich enucleosome, facilitating efficient enucleation during erythroid terminal differentiation.

eTNS1 is required to assemble F-actin into the enucleosome during enucleation of human erythroblasts. (A) Maximum intensity projections of Airyscan Z-stacks of polarized and enucleating human erythroblasts from day-14 cultures stained for F-actin (phalloidin; magenta), eTNS1 (red), GPA (green), and nuclei (Hoechst; blue). F-actin in eTNS1− cells assembled into mislocalized foci (yellow arrow), cables (red arrow), or was absent. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) Quantification of F-actin intensity in eTNS1− and eTNS1+ erythroblasts from eTNS1-KO cultures at days 14 and 17 using the Zeiss CD7. (C) Quantification of F-actin intensity normalized to GPA intensity of eTNS1+ and eTNS1− erythroblasts from eTNS1-KO cultures at days 14 and 17. (B-C) Plots reflect the mean ± SD of 1500 eTNS1+ and eTNS1− erythroblasts from 3 independent eTNS1 CRISPR KO experiments. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. a.u., arbitrary units.

eTNS1 is required to assemble F-actin into the enucleosome during enucleation of human erythroblasts. (A) Maximum intensity projections of Airyscan Z-stacks of polarized and enucleating human erythroblasts from day-14 cultures stained for F-actin (phalloidin; magenta), eTNS1 (red), GPA (green), and nuclei (Hoechst; blue). F-actin in eTNS1− cells assembled into mislocalized foci (yellow arrow), cables (red arrow), or was absent. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) Quantification of F-actin intensity in eTNS1− and eTNS1+ erythroblasts from eTNS1-KO cultures at days 14 and 17 using the Zeiss CD7. (C) Quantification of F-actin intensity normalized to GPA intensity of eTNS1+ and eTNS1− erythroblasts from eTNS1-KO cultures at days 14 and 17. (B-C) Plots reflect the mean ± SD of 1500 eTNS1+ and eTNS1− erythroblasts from 3 independent eTNS1 CRISPR KO experiments. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. a.u., arbitrary units.

Discussion

In this study, we adopted a data-mining approach to search for ABPs regulating F-actin assembly that were selectively upregulated late in human terminal erythroid differentiation. We identified a short isoform of TNS1,19-21 and confirmed this experimentally in human erythroid cells differentiated from CD34+ cells obtained from cord blood or adult bone marrow. eTNS1 is a novel short isoform (Mr ∼125 kDa) derived from an alternative exon 1E located in intron 17 of the canonical TNS1 transcript. eTNS1 is missing the FAB-N region of TNS1, including the ABD-I domain, as well as most of ABD-II within the unstructured region, but retains the FAB-C region containing the SH2 and PTB domains. Despite the absence of an ABD, using single-cell confocal microscopy analyses, we demonstrated that eTNS1 is required for F-actin assembly into the enucleosome and effective enucleation but not for assembly of the spectrin-actin membrane skeleton. Indeed, some nucleated eTNS1− cells were observed to form a biconcave-like shape despite retention of the nucleus.

The eTNS1 transcript appears to be primate specific, likely due to the presence of exon 1E within a long interspersed nuclear element leading to retrotransposition within this region of the genome,43 and is not present in mice or other rodents. Although the processes of terminal erythroid differentiation culminating in enucleation are broadly similar between mouse and human erythroblasts, global transcriptome analyses of human and murine erythropoiesis reveal significant differences that may reflect divergent physiological demands and provide insights into human hematological disorders.44 It is intriguing to consider that loss of eTNS1 function may account for some, as yet unidentified, causes of human congenital dyserythropoietic anemias in which nuclear extrusion is impaired or abnormal.45-47 Genetic diagnosis in cases of hereditary anemia, either by gene panels or whole-exome sequencing, reveals that many cases are not diagnosed when known hereditary anemia-associated genes are examined.48,49 In the human genome-wide association study catalog, single-nucleotide polymorphisms of TNS1 have been associated with erythroid cell traits: rs4672862 with erythrocyte count; and rs2571445, rs66678720, rs3796028, and rs1427669 with reticulocyte count.50-53

In human erythroblasts, the ABP Tmod1 plays an important role in regulating F-actin assembly, colocalizing with F-actin and NMIIB in the enucleosome, with loss of Tmod1 leading to reduced enucleation.15 However, unlike Tmod1, we did not observe colocalization between eTNS1 and F-actin in the enucleosome in polarized or enucleating eTNS1+ cells. Nevertheless, in absence of eTNS1, enucleation of erythroblasts was greatly impaired, and F-actin assembly was reduced and grossly abnormal, with eTNS1− cells containing long F-actin cables or aggregates, without an observable enucleosome. Because eTNS1 is missing ABD-I and ABD-II that interact with F-actin in canonical TNS1,54 and eTNS1 does not appear to form a stable complex with actin in erythroblasts (Figure 4C), eTNS1 may regulate F-actin polymerization and enucleation by activating signaling cascades mediated by SH2 and PTB domains in the conserved C-terminal domain of eTNS1,20-22,39,55-57 and/or via interactions of the unstructured domain with signaling molecules in biomolecular condensates, as shown for TNS1.58 In addition to F-actin assembly, eTNS1 signaling may also regulate other cytoskeletal mechanisms involved in erythroblast enucleation, including actomyosin contractility via NMIIB10,11,59 controlled by rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1 (ROCK1)/myosin light chain kinase (MLCK).10,16,60 The signaling functions of eTNS1 postulated here are based on structural similarity to TNS1 domains. However, despite high sequence conservation of eTNS1 with the C-terminal portion of TNS1, eTNS1 may have unique functions due to spatiotemporal localization and unique binding partners in erythroid cells, as seen with other members of the TNS family in different cell types (TNS1-4).20,21

In summary, our study identifies a novel isoform of TNS1 (eTNS1) expressed in late stages of human terminal erythroid differentiation that localizes to the cytoplasm during nuclear polarization and enucleation. eTNS1 is required for F-actin assembly and organization into the enucleosome, and for efficient enucleation of human erythroblasts to generate reticulocytes. Future studies will aim to further characterize the function of eTNS1, its binding partners, and how eTNS1 regulates the actin cytoskeleton during erythroblast enucleation. Elucidating the role of eTNS1 in the molecular pathways underlying F-actin polymerization in this complex cellular process may provide insights into species-specific functional differences between mouse and human erythroid cell physiology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lio Blanc and Julien Papoin at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research for initial assistance with human erythroid cell cultures, and Jack Mason at the University of Delaware with western blots and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

This research was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL083464; V.M.F.), a Core Access Award from Delaware IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE)/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) P20GM103446; V.M.F.) for use of the University of Delaware Bioimaging Center and Flow Cytometry Core, a grant from NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (R01DK111539; P.G.G.), and funds from the University of Delaware (V.M.F.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.G. was responsible for study conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, investigation, validation, writing of original draft manuscript, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript; M.C. was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, methodology, writing of the original draft manuscript, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript; D.M.D. was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript; S.B. was responsible for data curation, investigation, validation, and formal analysis; V.P.S. was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript; P.G.G. was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, visualization, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript; S.H.L. was responsible for study conceptualization, methodology, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript; and V.M.F. was responsible for study conceptualization, supervision, methodology, project administration, funding acquisition, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Velia M. Fowler, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Delaware, 105 The Green, 118 Wolf Hall, Newark, DE 19716; email: vfowler@udel.edu.

References

Author notes

A.G. and M.C. contributed equally to this study.

Actin-binding proteins upregulated in late stages of human erythroid terminal differentiation may be found in a data supplement available with the online version of this article.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Expression of TNS1 is upregulated during in vitro human terminal erythroid differentiation. (A) mRNA levels of TNS1, β-actin (ACTB), α1-spectrin (SPTA1), and protein 4.1R (EPB41) in CD34+ cell cultures on days 7, 11, and 14 of differentiation, measured by TaqMan quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Values are mean ± standard deviation [SD] from 5 individual CD34+ cultures. Fold-change in gene expression normalized to day 7 cells. ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (B) Representative western blots of TNS1, total actin, protein 4.1R, α1β1-spectrin, and total protein of differentiated CD34+ cells, and human U118 glioblastoma cells; 15 μg protein loaded per lane. Asterisk, full-length TNS1 in U118 cells (Mr ∼220 kDa); red arrow, immunoreactive TNS1 polypeptide in erythroid cells (Mr ∼125 kDa). (C) Quantification of immunoblots normalized to total protein. Band intensities analyzed by ImageJ. Values are mean ± SD from 6 individual CD34+ cultures. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) Maximum intensity projections of Airyscan Z-stacks of cells from day-14 cultures, before and at various stages of enucleation, stained for F-actin (red), TNS1 (magenta), GPA (green), and nuclei (blue). Scale bar, 5 μm. ns, non-significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/24/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025016100/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-016100-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1768555970&Signature=bkRdffdhjVzKyCqk-CvjuE-kvcH-sFM9CL72kErob5ltkHhCpTxoNRLelzQH6RJselZIa3DN5mD~soZiBN2g9OZTBZgEflhZO4ugYoWbM9hQoDnIp~sJqN9T1WTLwWb-XgqcyDFH0Ws31VC4ZK98sXFxaJvx2NxaOygbNrdVrrbe2SOg1-z6yK1V2BGwrwbaj5rtIFc9DpKrmI8bl0s~i7-eVs5bVfreS33J1CDl1tqODf9rKI11ZoJxY2NaBS8hLOy8iIzZ9Ui7H9XdaU7bdKVKUmUmfmDaM1OFs78EiRJvGyCpHcgrcIkrqJ2tPsq5~v2C~l1BOrjShKVc3ZY6AA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Human erythroblasts express a short isoform of TNS1 (eTNS1). (A) mRNA expression of TNS1 exons during human erythroid differentiation from human stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) through terminal differentiation to orthochromatic erythroblasts. Exons encoding the canonical Ensembl TNS1 mRNA transcript and the eTNS1 mRNA transcript are shown at the bottom, with location of alternate exon 1E containing initiator methionines denoted by arrows. Top, red: mRNA expression, determined by RNA-seq, increases during terminal erythroid differentiation starting at the early basophilic erythroblast stage. Middle, green: peaks of chromatin accessibility, determined by ATAC sequencing, at the promoter and in a putative intron-4 enhancer increase during terminal erythroid differentiation. Bottom, blue: peaks of histone marks and GATA1 and TAL1 transcription factor occupancy, determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing, in Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCa) and proerythroblasts. (B) Comparison of canonical TNS1 gene to eTNS1 short isoform (not to scale), including the unique eTNS1 start exon (1E) highlighted in magenta. Pre-designed TaqMan primer-probe pairs (I-V) were chosen to span the canonical TNS1 cDNA at the specific exon sites shown (Key: TaqMan Exon Probes). sgRNA (yellow triangle) location designed for CRISPR-Cas9 knockout experiments. Figure created with Biorender.com. (Diaz, D. 2025, https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/660ab6fdc5f830fa937a2f31) (C) Quantification of mRNA expression (qRT-PCR) calculated as 2(−ΔΔC[T]) for all 5 probes on days 7, 11, and 14 of erythroid cultures. Fold-change in gene expression normalized to average ΔCt value for day-7 cells for each of the 5 probes, using α-tubulin as a housekeeping gene. Values are mean ± SD from 3 individual erythroid cultures. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) Representative western blot for eTNS1, HA, total actin, and total protein in MDCK cells (full-length TNS1), CD34+ day-14 cells (eTNS1), untransfected HEK293T cells, and HEK293T cells transfected with an eTNS1-HA plasmid. Schematic in panel B created with BioRender.com. MDCK, Madin-Darby Canine Kidney; UTR, untranslated region.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/24/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025016100/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-016100-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1768555970&Signature=Aw~WkmSxOtsowll17i98oOEKglqXS2h-7nuAHOvoOAXt9aMnMXbdUBPKLvWIzoBIYYRVe1RwJAsDyOt8DT3mi73j9DQPoiOvd4L6h84u~T5~isI5Q54raNCDdt9nbaVU-4yQV1zvJdA1VMtG2kK0yfZYu6HPYwYekI9gqql8hfI9UVDMnRSbQLqd54TdPHxvrWjghrXhtYykwp5zQ8u1Ua6JCIC5now4J76d~uslRa8o53FKUnyKHoAVu6gAmN1sonVc3II2ZUKMYIPJIykTCYA-kuKjS-GNyg5EmlVZ7~GTvkw98rbSKMZ408mxqZfoTd7x70na-vboUtaPWpwReA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)