In this issue of Blood Advances, Buitrago et al1 report the results of a high-throughput, unbiased, and labor-intensive assay they conducted to identify blood clot contraction (retraction) inhibitors, producing a list that greatly expands known inhibitory compounds2 and suggests new mechanisms underlying platelet contractility.

Although many hematologists and scientists call this process retraction, we prefer the term clot contraction, because the basic process is similar to that of most other cells, involving contractile proteins including actin, myosin, and associated proteins. Clot contraction is a later stage of blood clotting, during which the clot shrinks in size, caused by activated platelets pulling on fibrin fibers, which results in the redistribution of fibrin and platelets to the exterior and tight packing of erythrocytes on the interior.3 The consequence is that red blood cells change their customary biconcave shape as a result of compressive forces to become polyhedral (so-called polyhedrocytes), and the clots become dense, stiff, and impermeable. Clot contraction also occurs in intravital clots and thrombi, which results in very little space between structures that make up thrombi.4 Consequently, clot contraction is important for creating a better seal to stem bleeding in hemostasis, reducing the obstructiveness of thrombi, and perhaps for wound healing.5

This is an impressive study for several reasons. It is difficult to isolate platelet-driven blood clot contraction from other platelet functions because they are closely linked, and most inhibitors of clot contraction also affect other platelet activities. Platelet aggregation, mediated by the interaction of fibrinogen with the active integrin αIIbβ3 molecules on the surface of adjacent platelets, is especially difficult to separate from clot contraction with strong αIIbβ3-fibrin interactions. To distinguish between the 2 processes, the authors exploit their observation that platelets treated with the αIIbβ3 antagonist peptide RGDW, which mostly eliminates fibrinogen-mediated platelet aggregation, are still able to contract clots.6 Although it is a relative, rather than an absolute, effect, the authors realized that it can be used as the basis for a high-throughput assay for compounds affecting clot contraction somewhat selectively.

The scale of the screen described in this article is remarkable. They tested 1280 compounds from the Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds and 8430 compounds from various drug-repurposing libraries. They identified 162 compounds from both libraries as inhibitors of clot contraction, and these compounds were categorized based on the activity of their reported targets (see figure). Although the title of this commentary uses “ubiquitous” to pair with “ubiquitin,” and because there were many hits, this represents a hit rate of 1.7%. In the list, there are many inhibitors of kinases and phosphodiesterases, blockers of various receptors and ubiquitination/deubiquitination reactions, as well as pharmacological agents with targets that have not been previously reported to have antiplatelet activity categorized as “other.” It is important to remember that this screening assay is not specific to clot contraction, because it depends on all the prior events, including platelet activation, subsequent signaling, fibrin formation, and fibrin-platelet interactions. This is obvious from some of the hits that are clearly not specific to clot contraction. Thus, the compounds on this list need further testing. Nevertheless, the new compounds and hitherto unknown pharmacological targets that may be related to blood clot contraction provide a basis for future studies, which may lead to the discovery of other novel mechanisms and new treatments of hemostatic disorders, including thrombosis.

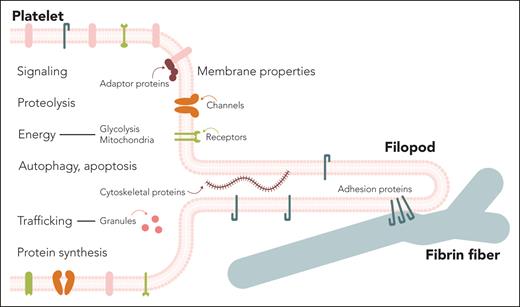

Cellular and extracellular processes and structures that might be pharmacological targets to inhibit blood clot contraction. The figure illustrates the basic cellular mechanism of clot contraction: an activated platelet extends a filopod containing the adhesion protein integrin αIIbβ3 in its membrane, which attaches to a fibrin fiber and pulls on it, creating a kink and thereby contracting the fibrin network and the entire clot. Dynamic cytoskeletal proteins are responsible for cycles of extension and retraction of multiple filopodia formed in a single platelet. The text inside and outside of the platelet designates the structures and processes that can be affected by the molecules identified in the screen described in the article by Buitrago et al.1 Professional illustration by somersault18:24 Studio BV.

Cellular and extracellular processes and structures that might be pharmacological targets to inhibit blood clot contraction. The figure illustrates the basic cellular mechanism of clot contraction: an activated platelet extends a filopod containing the adhesion protein integrin αIIbβ3 in its membrane, which attaches to a fibrin fiber and pulls on it, creating a kink and thereby contracting the fibrin network and the entire clot. Dynamic cytoskeletal proteins are responsible for cycles of extension and retraction of multiple filopodia formed in a single platelet. The text inside and outside of the platelet designates the structures and processes that can be affected by the molecules identified in the screen described in the article by Buitrago et al.1 Professional illustration by somersault18:24 Studio BV.

As a proof-of-concept study, the authors did preliminary testing of a deubiquitinase inhibitor, degrasyn. Ubiquitination is the process by which the cell can regulate the presence of certain proteins by marking unwanted proteins with a label consisting of the polypeptide ubiquitin. Proteins attached to ubiquitin are then degraded rapidly in proteasomes, the so-called cellular “waste disposers.” Deubiquitinating enzymes are a large group of proteases that cleave ubiquitin from proteins, thereby playing an antagonistic role in this process of intracellular protein degradation by removing ubiquitin and reversing the fate of the proteins. Degrasyn is a selective inhibitor of deubiquitinating enzymes, leading to rapid accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins into aggresomes around the nucleus and promoting tumor cell apoptosis. In this study, degrasyn was identified as an inhibitor of clot contraction without affecting thrombin or von Willebrand factor–induced platelet aggregation. The study indicates that the effects of degrasyn are downstream of thrombin-induced platelet aggregation and thus may permit the separation of platelet aggregation from clot contraction. Degrasyn also impairs actin polymerization by suppressing cofilin activity and increases cofilin oxidation.7 The potential role of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in platelet cytoskeletal biology is interesting, and the results of further experiments could have wide and important mechanistic and therapeutic implications.

The benefits of inhibition of blood clot contraction in vivo are that therapeutic thrombolysis will be more effective, because thrombi will be more permeable and accessible to thrombolytic enzymes and other drugs, and thrombi will be less stiff, stable, and potentially easier to remove via mechanical thrombectomy. The success of these studies suggests that, in the future, it may also be worth considering a screen for drugs to increase blood clot contraction, which would make thrombi less obstructive and less likely to embolize.

Overall, the results of the assay are not only of great potential practical importance, but they are quite thought provoking. Most importantly, the authors found a long list of candidate inhibitors that could form the basis for many years of further research on platelet function, including contractility and mechanotransduction. Some compounds in the list that are not even mentioned in the text are intriguing. For example, one hit has as its target calpain, which appears to play a role in clot contraction by releasing the connection between the cytoskeleton and platelet integrins to allow more cycles of contractility, similar to what it does in cell motility.8 After a period of relative inactivity in research on blood clot contraction, this process has become an intensely studied aspect of hemostasis and thrombosis, and the future of investigation in this area is bright.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.