TO THE EDITOR:

The development of anti-B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–directed chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts) is a practice-changing milestone for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), with idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel becoming a novel standard of care for patients with relapsed/refractory MM.1-4 As the treatment landscape of MM increasingly shifts toward personalized immunotherapies, emerging data indicate that T-cell–engaging therapies are less effective in patients with exhausted or contracted T-cell phenotypes.5-7 Novel mechanisms of action are therefore needed to optimize the efficacy and durability of CAR-T therapy in MM.

In this study, we aimed to redefine the role of programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) inhibition in MM by investigating its potential as a salvage treatment in the context of emerging relapse to anti-BCMA CAR-T therapy. We hypothesized that (1) post–CAR-T treatment with the anti–PD-1 antibody nivolumab may recapture sensitivity to CAR-Ts in selected patients and (2) the clinical response to nivolumab is dictated by the state of the non–CAR-Ts at the time of treatment.

Four patients treated with ide-cel as part of the first-in-human CRB401 phase 1 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02658929)8 received a combination of nivolumab, an immunomodulatory drug (lenalidomide, pomalidomide), and dexamethasone at the time of relapse to first or second ide-cel infusion (Table 1). Treatment was conducted at the Massachusetts General Hospital in accordance with the institutional review board–approved protocol and the Declaration of Helsinki. Median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival after ide-cel were 10.4 months (range, 3.0-13.8) and 21.5 months (range, 16.0-34.6), respectively, matching the results from the previously reported phase 2 and 3 trials.1,3 Responses to nivolumab-based salvage therapy included 1 patient with a partial response, 1 with stable disease, and 2 with progressive disease according to International Myeloma Working Group criteria, amounting to a mean time-to-next treatment on nivolumab of 4.0 months (median 3.6, range, 0.4-8.0).

Patient characteristics

| . | MM1 . | MM2 . | MM3 . | MM4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | 37 | 50 | 47 | 56 |

| Age at CAR-T therapy | 40 | 55 | 51 | 61 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Female |

| MM subtype | IgA κ | IgG κ | IgG λ | κ light chain |

| ISS stage | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Cytogenetics | HR | SR | HR | SR |

| Previous ASCT | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Penta-refractory disease | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BM-PC before ide-cel, % | <5 | 10 | 80 | 2 |

| Outcome on nivolumab-based salvage therapy | ||||

| PFS after first CAR-T, mo | 13.6 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 3.0 |

| Best response to first CAR-T | CR | CR | VGPR | VGPR |

| PFS after second CAR-T, mo | 1.4 | 1.3 | 5.1 | Not infused |

| Best response to second CAR-T | PD | PD | PR | Not infused |

| Salvage regimen | Nivo-Rd | Nivo-Pd | Nivo-Pd | Nivo-Rd |

| TTNT, mo | 0.4 | 3.4 | 8.0 | 3.6 |

| Best response | PD | PR | SD | PD |

| Subsequent therapy | KC(d) | DRd | Tec | DVd |

| . | MM1 . | MM2 . | MM3 . | MM4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | 37 | 50 | 47 | 56 |

| Age at CAR-T therapy | 40 | 55 | 51 | 61 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Female |

| MM subtype | IgA κ | IgG κ | IgG λ | κ light chain |

| ISS stage | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Cytogenetics | HR | SR | HR | SR |

| Previous ASCT | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Penta-refractory disease | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BM-PC before ide-cel, % | <5 | 10 | 80 | 2 |

| Outcome on nivolumab-based salvage therapy | ||||

| PFS after first CAR-T, mo | 13.6 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 3.0 |

| Best response to first CAR-T | CR | CR | VGPR | VGPR |

| PFS after second CAR-T, mo | 1.4 | 1.3 | 5.1 | Not infused |

| Best response to second CAR-T | PD | PD | PR | Not infused |

| Salvage regimen | Nivo-Rd | Nivo-Pd | Nivo-Pd | Nivo-Rd |

| TTNT, mo | 0.4 | 3.4 | 8.0 | 3.6 |

| Best response | PD | PR | SD | PD |

| Subsequent therapy | KC(d) | DRd | Tec | DVd |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; BM-PC, bone marrow plasma cell; DRd, daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; DVd, daratumumab-bortezomib-dexamethasone; HR, cytogenetic high risk (defined as del17p, t(4;14), t(14;16), ampl1q); ISS, International Staging System; KC(d), carfilzomib-cyclophosphamide(-dexamethasone); IgA/G, immunoglobulin A/G; Nivo, nivolumab; Pd, pomalidomide-dexamethasone; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; Rd, lenalidomide-dexamethasone; SD, stable disease; SR, cytogenetic standard risk (all aberrations except from HR); Tec, teclistamab; TTNT, time-to-next treatment; VGPR, very good partial response.

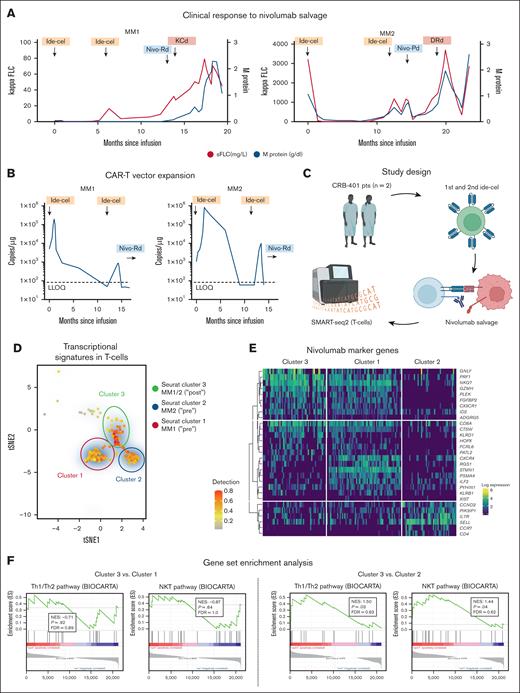

To more closely investigate patterns of response to ide-cel, we dissected the cases of the following 2 patients: MM1, a 40-year-old man with immunoglobulin A kappa MM and a complete response to ide-cel with a PFS of 13.6 months, and MM2, a 55-year-old man with immunoglobulin G kappa MM who also achieved complete response to first ide-cel infusion with a PFS of 11.7 months (Figure 1A). At relapse to first CAR-T infusion, a second ide-cel dose was given as part of the CRB-401 trial protocol but remained ineffective in MM1 and MM2 despite reexpansion of the CAR-T vector (Figure 1B). Strikingly, the efficacy of a subsequent nivolumab-based salvage therapy differed remarkably between both patients. Although nivolumab remained without benefit in MM1, it led to a partial response and clinically meaningful PFS of 3.4 months in MM2 (Table 1). As no antidrug antibodies were detected in both patients, this observation pointed toward a different mode of nivolumab efficacy in MM2. To better elucidate the T-cell state, we next investigated the transcriptional heterogeneity of non–CAR CD3+ T cells from the peripheral blood of MM1 and MM2 at single-cell resolution using full-length single-cell RNA sequencing before and after salvage therapy with nivolumab (Figure 1C). A total of 1047 cells were analyzed and underwent quality control filtering (supplemental Figure 1). Profiling of these non–CAR-T subsets by single-cell RNA sequencing revealed rapid cellular state changes in response to PD-1 inhibition (Figure 1D). PAGODA2 clustering and t-Stochastic Neighbor Embedding identified a diverging composition of populations with a deranged T-cell fitness state in cluster 2 (enriched for MM2 before nivolumab; supplemental Figure 2) which was characterized by the absence of CD8A, ILF2, CTSW, PRF1, and GZMH, along with deficient T helper 1 cells/T helper 2 cells and natural killer T cell pathway signaling (Figure 1E-F). Opposingly, the transcriptional signature in cluster 1 (enriched for baseline T cells from MM1; supplemental Figure 2) was indicative of intact T-cell fitness with high expression of CXCR4, NKG7, and ILF2. In both patients, nivolumab led to rapid changes toward more effective T-cell states (cluster 3). Yet, these state changes only translated into a clinical benefit in MM2, who had a more susceptible, hyporesponsive T-cell state at entry point, whereas no significant amelioration of transcriptional T-cell activity nor clinical benefit to nivolumab could be noted in MM1.

Nivolumab to salvage T-cell fitness in CAR-T refractory MM. (A) The serologic response to ide-cel and nivolumab-based salvage therapy in MM1 (left panel) and MM2 (right panel). (B) CAR-T vector expansion over time indicating the time of first and second ide-cel infusion. (C) Study design for correlative T-cell assessment. (D) A tSNE plot of single CD3+ non–CAR-Ts, showing 3 distinct clusters relating to treatment with nivolumab-based salvage therapy. (E) The heat map in panel E visualizes cluster characterization by marker gene expression for clusters 1, 2, and 3. (F) Gene set enrichment plots show expressed gene sets derived from the BIOCARTA T helper 1 cells/T helper 2 cells and BIOCARTA natural killer T cell pathway in MM1 (cluster 3 vs 1) and MM2 (cluster 3 vs 2). DRd, daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; FDR, false discovery rate; FLC, free light chain; KCd, carfilzomib-cyclophosphamide(-dexamethasone); NES, normalized enrichment score; Nivo, nivolumab; Pd, pomalidomide-dexamethasone; pts, patients; Rd, lenalidomide-dexamethasone; sFLC, serum-free light chain; tSNE, t-stochastic network embedding. Figure panel C created with BioRender (https://BioRender.com/i46u828#).

Nivolumab to salvage T-cell fitness in CAR-T refractory MM. (A) The serologic response to ide-cel and nivolumab-based salvage therapy in MM1 (left panel) and MM2 (right panel). (B) CAR-T vector expansion over time indicating the time of first and second ide-cel infusion. (C) Study design for correlative T-cell assessment. (D) A tSNE plot of single CD3+ non–CAR-Ts, showing 3 distinct clusters relating to treatment with nivolumab-based salvage therapy. (E) The heat map in panel E visualizes cluster characterization by marker gene expression for clusters 1, 2, and 3. (F) Gene set enrichment plots show expressed gene sets derived from the BIOCARTA T helper 1 cells/T helper 2 cells and BIOCARTA natural killer T cell pathway in MM1 (cluster 3 vs 1) and MM2 (cluster 3 vs 2). DRd, daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; FDR, false discovery rate; FLC, free light chain; KCd, carfilzomib-cyclophosphamide(-dexamethasone); NES, normalized enrichment score; Nivo, nivolumab; Pd, pomalidomide-dexamethasone; pts, patients; Rd, lenalidomide-dexamethasone; sFLC, serum-free light chain; tSNE, t-stochastic network embedding. Figure panel C created with BioRender (https://BioRender.com/i46u828#).

These results add to the current understanding of cellular therapies in hematologic malignancies. CAR-Ts do not act independently but rely on critical interaction with the tumor microenvironment, where hyporesponsive T-cell states in the non-CAR population may foster suboptimal efficacy and longevity.9-11 T-cell activation and expansion initiate on antigen stimulation, but tonic signaling may also negatively affect CAR-T persistence and fitness.12 Antibodies targeting the immune checkpoint PD-1 have revolutionized the treatment of many cancers. However, in light of worse outcomes in KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185,13,14 checkpoint inhibition is being less actively pursued in MM.15

In spite of the small number of patients in this case study, our data redefine the role of checkpoint inhibition in the context of cellular therapies in MM as it demonstrates the feasibility and efficacy of nivolumab to reinduce treatment responses to CAR-Ts. On the basis of our findings and previous data,16,17 this therapeutic approach, however, seems warranted only in a well-selected subgroup of patients, given that the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors as a way to resurrect CAR-Ts is very dependent on the state of the T-cell microenvironment at the time of relapse to CAR-T. To this end, testing of the T-cell microenvironment may become an imperative prerequisite before giving checkpoint blockade after CAR-T.

In summary, we here provide a blueprint for real-time serial profiling of T-cell activation states in the non–CAR-T population in the course of CAR-T therapy. Our approach may provide patient-tailored molecular rationales for transcriptome-driven therapeutic concepts in the context of CAR-T therapy for MM. In parallel, antigen escape strategies, including phenotypic and/or genomic loss of the BCMA-coding gene TNFRSF17, may depict alternative drivers of CAR-T resistance18-20 and could equally be monitored by serial profiling in a similar platform.

The ideal timing of checkpoint inhibition still requires further exploration, as it may be even more beneficial as a preemptive consolidation strategy after CAR-T to improve early vector expansion in vivo. Although the concept of combined CAR-T and checkpoint inhibition is not being pursued in current clinical trials for MM, armored CAR-Ts, secreting checkpoint inhibitors to avoid immunosuppression, are being investigated in solid cancers. In MM, the TRIMM-3 trial platform evaluates the potential of the anti–PD-1 antibody cemiplimab in combination with the anti–BCMA bispecific antibody teclistamab and the anti–GPRC5D bispecific antibody talquetamab (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05338775).

Outcomes for this trial have not been reported yet but are eagerly awaited to demonstrate the feasibility and safety of PD-1 inhibition as resensitizing strategy in the context of T-cell–based immunotherapies for MM.

Acknowledgments: J.M.W. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship of Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (391926441) and a research grant from the Germany Federal Ministry of Education and Research. N.S.R. is supported by a grant from the Paula and Rodger Riney Foundation. J.G.L. is supported by National Cancer Institute grant R37CA276044.

Contribution: J.M.W., J.G.L., and N.S.R. designed the research design and wrote the manuscript; J.M.W., N.S., S.A., T.V., P.A., and H.S. performed research and statistical analysis; J.M.W. and S.A. collected data; J.M.W., N.S., S.A., T.V., B.K., J.G.L., and N.S.R. analyzed and interpreted data; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.M.W. has served as a consultant for Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Takeda, Pfizer, Oncopeptides, and Skyline Dx; received honoraria from Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), PharmaMar, and BeiGene; and has received research support from Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS). T.C., S.M.K., and X.Z. are current or past employees of BMS. K.C.A. has consulted for Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca, and is a founder and/or board member of C4 Therapeutics, Starton, Window, Dynamic Cell Therapies, and Predicta Biosciences. H.E. has consulted for BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Amgen, Takeda, Sanofi, GSK, and Novartis; discloses research funding from BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Amgen, GSK, and Sanofi; has received honoraria from BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Amgen, Takeda, Sanofi, GSK, and Novartis; and received travel support from BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Amgen, Takeda, Novartis, and Sanofi. A.J.Y. has consulted for AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Karyopharm, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Prothena, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sebia, and Takeda, and has received research funding to institution from Amgen, BMS, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, and Sanofi. N.S.R. has consulted for Amgen, BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Takeda, AstraZeneca, and C4 Therapeutics; has participated in advisory boards for Caribou and Immuneel; and received research funding from bluebird bio. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Noopur S. Raje, Center for Multiple Myeloma, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 55 Fruit St, Boston, MA 02114; email: nraje@mgh.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

J.M.W., N.S., S.A., and T.V. contributed equally as first authors.

B.K., J.G.L., and N.S.R. contributed equally as last authors.

Primary results were presented, in part, at the 64th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, New Orleans, LA, 10-13 December 2022.

Sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE286237).

Codes used for all analyses are available on request from the corresponding author, Noopur S. Raje (nraje@mgh.harvard.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.