Key Points

B-cell maturation antigen–directed CAR-T therapy in patients with MM and CNS involvement is feasible without excess neurotoxicity.

Data support CNS myeloma screening, optimized bridging, and CNS-targeted treatment before CAR-T therapy in high-risk patients.

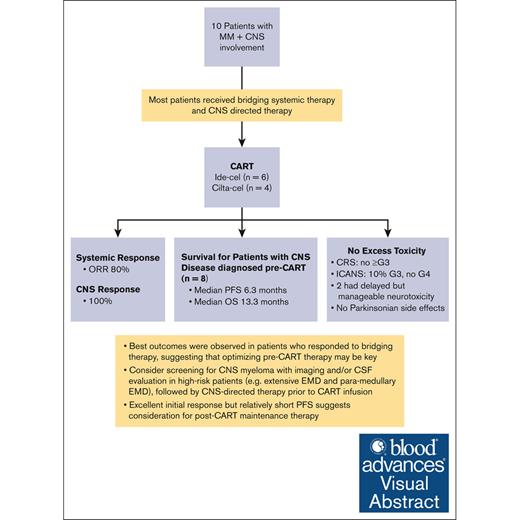

Visual Abstract

We investigated B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM) and central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Ten patients received either idecabtagene vicleucel (n = 6) or ciltacabtagene autoleucel (n = 4), where brain/cranial nerve and/or spinal cord involvement/leptomeningeal disease were evident on either magnetic resonance imaging (100%) and/or cerebrospinal fluid (40%). Eight patients had their CNS diagnosis before CAR-T therapy, and two were diagnosed within 14 days post-infusion. Seven received CNS-directed therapy during bridging before CAR-T therapy. There were no excess toxicities: no cytokine release syndrome grade ≥3; 10% immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) grade 3; and no ICANS grade 4. Two patients experienced delayed but treatable neurotoxicity, with no reported parkinsonian side effects. The best overall response rate was 80% (≥70% very good partial response) and a 100% CNS response. With a median follow-up of 381 days, patients with CNS myeloma diagnosed before CAR-T therapy (n = 8) had a median overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS) of 13.3 and 6.3 months, respectively. Best outcomes were observed in 4 patients who had a response to bridging therapy, suggesting that optimizing pre-CAR-T therapy may be key for improved outcomes. Our study suggests that CAR-T therapy in patients with CNS MM is safe and feasible, and screening for CNS involvement before CAR-T therapy could be warranted in high-risk patients. The excellent initial response but relatively short PFS suggests consideration for post-CAR-T maintenance. Larger studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a breakthrough in the therapeutic armamentarium available for patients with hematologic malignancies, including relapsed or refractory (R/R) multiple myeloma (MM). B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) is a protein that belongs to the tumor necrosis factor superfamily and has become an attractive therapeutic target given its expression on the surface of myeloma cells and downstream signaling role in supporting malignant cell survival and proliferation.1 After the success of CD19 CAR T-cell therapy in B-cell malignancies,2-4 BCMA CAR T-cell therapy was explored in patients with R/R MM in the KarMMa, LEGEND-2, and CARTITUDE clinical trials.5-7 The outcomes revolutionized the MM therapeutic landscape, with unparalleled outcomes in a heavily pretreated population. Currently, 2 US Food and Drug Administration–approved CAR T-cell therapy products are approved in the United States, idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel). Ide-cel was evaluated in the KarMMa clinical trial, in which 128 patients with R/R MM received the product, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 73%, median progression-free survival (PFS) of 8.8 months, and overall survival (OS) of 19.4 months.5 Moreover, 97 patients received cilta-cel on the CARTITUDE clinical trial, demonstrating an ORR of 97%, 12-month PFS of 77%, and 12-month OS of 89%.6

Patients with MM and central nervous system (CNS) involvement have historically had a poor prognosis, with limited therapeutic options. Despite the remarkable advances in CAR T-cell therapy, patients with CNS disease have been excluded from the pivotal clinical trials of the currently approved BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapies, ide-cel and cilta-cel.5,6 These patients can now receive commercially available BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapies; however, the clinical experience has remained limited with the concern that such therapy may potentially increase the incidence or severity of neurotoxicity or immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). Scarce data questioned whether BCMA expression on neural tissue such as the substantia nigra could be implicated in the pathophysiology of parkinsonian-like effects and delayed neurotoxicity that developed in a few patients after BCMA CAR T-cell therapy,8,9 further limiting the use of CAR T-cell therapy in this patient population to large academic centers, with very few patients having received it.

Previously, CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy has been shown to be effective and safe in the treatment of patients with CNS lymphoma, without excess toxicity or the development of excess ICANS.10-12 Importantly, data showed that CAR+ T cells were able to successfully cross the blood-brain barrier into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).10,13,14 Given the dire need for new therapies for patients with CNS MM and that there seems to be sufficient evidence from other CAR T-cell products in B-cell malignancies that CAR T cells can migrate into the CSF and exert antitumor activity, we conducted this study to investigate the safety and efficacy of BCMA-directed therapies in patients with MM and CNS involvement.

Methods

Participants

This study is a multicenter, retrospective analysis from 5 major US academic cancer centers including patients with MM with CNS involvement who received BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy, either ide-cel or cilta-cel. Ten patients with MM and CNS involvement who received BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy were included in this analysis, with 6 and 4 patients receiving ide-cel and cilta-cel, respectively.

Patients were eligible if they were adults diagnosed with MM according to the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria and exhibited CNS involvement confirmed by positive findings on brain or spinal cord imaging or by CSF studies. The study included those who received prior CNS-directed radiation or intrathecal (IT) chemotherapy, regardless of the timeline in relation to CAR T-cell therapy, as well as those who had not received any prior CNS-directed therapy. Additionally, the study included patients who were diagnosed with CNS involvement within 14 days after receiving the CAR T-cell infusion. The study was conducted after institutional review board approval and according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines.

Objectives, end points, and statistical methods

The objectives were to assess the safety and efficacy of both ide-cel and cilta-cel therapy in patients with MM with CNS involvement. The primary end points were the incidence rates of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and ICANS. Secondary end points were the best response rates and CNS response after CAR T-cell therapy. We used descriptive statistics in reporting our data, in which categorical covariates were summarized with frequencies and percentages, and continuous covariates were assessed using medians and ranges. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the OS and PFS using IBM SPSS statistics 24.

Evaluation of responses and CNS disease

Diagnosis of MM, responses to therapies, and progression were determined according to the IMWG criteria and per investigator discretion.15,16 CNS disease was evaluated using brain imaging, spine imaging, and CSF evaluation. Positive CNS disease was established if a patient had either positive findings on imaging of brain or spinal cord or if the CSF was positive for malignant plasma cells. CNS response was determined by an improvement on subsequent imaging and/or clearance of malignant plasma cells from the CSF after CAR T-cell infusion. Response assessments were conducted at regular intervals after CAR T-cell therapy, and the best response rates achieved were determined. Minimal/measurable residual disease (MRD) assessment varied based on institutional standards, in which both flow cytometry and next-generation sequencing (eg, clonoSEQ) were acceptable methods for assessment. The flow cytometry sensitivity varied per institution, with 105 as the minimum sensitivity required per IMWG consensus definition of MRD negativity.

Results

Patient and disease characteristics

Our study included 10 patients with MM and CNS involvement who received either ide-cel (n = 6) or cilta-cel (n = 4). Patients had a median age of 58 years (range, 36-71), 70% were male, 20% were Black, and 40% had high-risk (HR) cytogenetics (Table 1). The median number of prior lines of therapy was 6 (range, 4-10), with the majority of patients being triple-class refractory (80%) and penta-class refractory (70%). Three patients (30%) had prior BCMA-directed therapy.

Patient and disease characteristics

| Characteristic . | Value (n = 10) . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 58 (36-71) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 3 | 30 |

| Male | 7 | 70 |

| Race | ||

| White | 3 | 30 |

| Black | 2 | 20 |

| Caucasian | 3 | 30 |

| Asian | 1 | 10 |

| Others | 1 | 10 |

| MM subtype | ||

| IgG | 7 | 70 |

| IgA | 1 | 10 |

| Light chain only | 2 | 20 |

| Light chain | ||

| Kappa | 6 | 60 |

| Lambda | 4 | 40 |

| HR FISH/CG | ||

| Yes | 4 | 40 |

| No | 4 | 40 |

| Unknown | 2 | 20 |

| t(4,14) | ||

| Yes | 1 | 10 |

| No | 7 | 70 |

| Unknown | 2 | 20 |

| t(4,16) | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 8 | 80 |

| Unknown | 2 | 20 |

| del(17p) | ||

| Yes | 1 | 10 |

| No | 7 | 70 |

| Unknown | 2 | 20 |

| 1q21 gain/amp | ||

| Yes | 4 | 40 |

| No | 5 | 50 |

| Unknown | 1 | 10 |

| R-ISS | ||

| I | 1 | 10 |

| II | 4 | 40 |

| III | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 5 | 50 |

| ECOG | ||

| 0 | 1 | 10 |

| 1 | 6 | 60 |

| 2 | 3 | 30 |

| 3-4 | 0 | 0 |

| Extramedullary disease | ||

| CNS EMD | 10 | 100 |

| Non-CNS extraosseous EMD | 6 | 60 |

| Para-medullary EMD | 3 | 30 |

| Number of prior lines of therapy, median (range) | 6 (4-10) | |

| Prior ASCT | ||

| Yes | 9 | 90 |

| No | 1 | 10 |

| Triple-class refractory∗ | ||

| Yes | 8 | 80 |

| No | 2 | 20 |

| Penta-class refractory† | ||

| Yes | 7 | 70 |

| No | 3 | 30 |

| Prior BCMA-directed therapy | ||

| Yes | 3 | 30 |

| No | 7 | 70 |

| Characteristic . | Value (n = 10) . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 58 (36-71) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 3 | 30 |

| Male | 7 | 70 |

| Race | ||

| White | 3 | 30 |

| Black | 2 | 20 |

| Caucasian | 3 | 30 |

| Asian | 1 | 10 |

| Others | 1 | 10 |

| MM subtype | ||

| IgG | 7 | 70 |

| IgA | 1 | 10 |

| Light chain only | 2 | 20 |

| Light chain | ||

| Kappa | 6 | 60 |

| Lambda | 4 | 40 |

| HR FISH/CG | ||

| Yes | 4 | 40 |

| No | 4 | 40 |

| Unknown | 2 | 20 |

| t(4,14) | ||

| Yes | 1 | 10 |

| No | 7 | 70 |

| Unknown | 2 | 20 |

| t(4,16) | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 8 | 80 |

| Unknown | 2 | 20 |

| del(17p) | ||

| Yes | 1 | 10 |

| No | 7 | 70 |

| Unknown | 2 | 20 |

| 1q21 gain/amp | ||

| Yes | 4 | 40 |

| No | 5 | 50 |

| Unknown | 1 | 10 |

| R-ISS | ||

| I | 1 | 10 |

| II | 4 | 40 |

| III | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 5 | 50 |

| ECOG | ||

| 0 | 1 | 10 |

| 1 | 6 | 60 |

| 2 | 3 | 30 |

| 3-4 | 0 | 0 |

| Extramedullary disease | ||

| CNS EMD | 10 | 100 |

| Non-CNS extraosseous EMD | 6 | 60 |

| Para-medullary EMD | 3 | 30 |

| Number of prior lines of therapy, median (range) | 6 (4-10) | |

| Prior ASCT | ||

| Yes | 9 | 90 |

| No | 1 | 10 |

| Triple-class refractory∗ | ||

| Yes | 8 | 80 |

| No | 2 | 20 |

| Penta-class refractory† | ||

| Yes | 7 | 70 |

| No | 3 | 30 |

| Prior BCMA-directed therapy | ||

| Yes | 3 | 30 |

| No | 7 | 70 |

Amp, amplification; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; CG, Cytogenetics; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; R-ISS, Revised Multiple Myeloma International Staging System.

Triple-class refractory was defined as MM refractory to an immunomodulatory (IMiD) drug, a proteosome inhibitor (PI), and an anti-CD38 antibody.

Penta-class refractory was defined as MM refractory to 2 IMiDs, 2 PIs, and an anti-CD38 antibody.

Four patients (40%) had brain and/or cranial nerve involvement only, and 6 patients (60%) had both brain/cranial nerve and spinal cord involvement/leptomeningeal disease (Table 2). CNS disease was evident on magnetic resonance imaging brain or spinal cord in all the patients. Four patients (40%) had positive malignant cells on CSF evaluation, 2 patients had negative CSF results, and 4 patients did not have CSF evaluation data available.

CNS disease characteristics and treatments

| Characteristic . | Value (n = 10) . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| CNS disease | ||

| Brain/cranial nerve involvement only | 4 | 40 |

| Both brain/cranial nerve and spinal cord involvement | 6 | 60 |

| MRI abnormalities at diagnosis of CNS disease | ||

| Yes | 10 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 |

| CSF abnormal at diagnosis of CNS disease | ||

| Yes | 4 | 40 |

| No | 2 | 20 |

| N/A | 4 | 40 |

| No. of days between CNS disease diagnosis to CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| ≤30 d, n, median (range) | 2, 26 (21-30) | 20 |

| 31-60 d, n, median (range) | 3, 42 (34-56) | 30 |

| >300 d, n, median (range) | 3, 587 (344-710) | 30 |

| Diagnosed soon after CAR T-cell therapy, n, median (range) | 2∗ | 20 |

| CNS-directed therapy | ||

| Part of bridging therapy before CAR T-cell therapy† | ||

| RT (brain and/or spine) | 2 | 20 |

| IT chemotherapy | 1 | 10 |

| RT + IT chemotherapy | 3 | 30 |

| Surgery + RT | 1 | 10 |

| Post-CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| RT after CAR T-cell therapy | 2 | 20 |

| None (due to recent DCEP chemotherapy) | 1 | 10 |

| No. of days between last RT session and CAR T-cell infusion | ||

| Median (range) | 14.5 (9-39) | |

| Systemic bridging therapy‡ | ||

| mCBAD | 1 | 10 |

| KCd (±RT) | 2 | 20 |

| Vd (±revlimid ± RT) | 2 | 20 |

| DCEP (±RT) | 2 | 20 |

| PXd (+RT) | 1 | 10 |

| VD-CE (+IT chemotherapy and RT) | 1 | 10 |

| Dara-Pom-Dex+Seli (+IT chemotherapy and RT) | 1 | 10 |

| Treated vs untreated known CNS disease at time of LDC (n = 8)§ | ||

| Treated | 7/8 | 87.5 |

| Untreated | 1/8 | 12.5 |

| CAR T-cell product | ||

| Ide-cel | 6 | 60 |

| Cilta-cel | 4 | 40 |

| CAR T-cell dose | ||

| Ide-cel median (range) million cells | 427 (154-447) | |

| Cilta-cel | ||

| Median (range) dose, ×106 CAR+ per kg | 0.7 (0.6-0.7) | |

| Median (range) million cells | 54 (47-61) | |

| CAR T-cell manufacturing | ||

| Out-of-specification products | 0 | 0 |

| Successful manufacturing on first attempt | 9 | 90 |

| Successful manufacturing on second attempt | 1 | 10 |

| Lymphodepletion received before CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| Fludarabine and cyclophosphamide | 10 | 100 |

| Treatments after CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| CNS-directed RT | 2 | 20 |

| For 2 patients with CNS disease diagnosed after CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| In one of them this was followed by Elo-Pom-Dex, VD-AC, and teclistamab | ||

| Pomalidomide-based therapy | ||

| Daratumumab-pomalidomide-dexamethasone | 1 | 10 |

| Selinexor-pomalidomide-dexamethasone ± IT chemotherapy ± RT | 2 | 20 |

| Isatuximab-carfilzomib-dexamethasone | 2 | 20 |

| BCMA-directed bispecific therapy (teclistamab) | 1 | 10 |

| None or N/A | 2 | 20 |

| Characteristic . | Value (n = 10) . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| CNS disease | ||

| Brain/cranial nerve involvement only | 4 | 40 |

| Both brain/cranial nerve and spinal cord involvement | 6 | 60 |

| MRI abnormalities at diagnosis of CNS disease | ||

| Yes | 10 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 |

| CSF abnormal at diagnosis of CNS disease | ||

| Yes | 4 | 40 |

| No | 2 | 20 |

| N/A | 4 | 40 |

| No. of days between CNS disease diagnosis to CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| ≤30 d, n, median (range) | 2, 26 (21-30) | 20 |

| 31-60 d, n, median (range) | 3, 42 (34-56) | 30 |

| >300 d, n, median (range) | 3, 587 (344-710) | 30 |

| Diagnosed soon after CAR T-cell therapy, n, median (range) | 2∗ | 20 |

| CNS-directed therapy | ||

| Part of bridging therapy before CAR T-cell therapy† | ||

| RT (brain and/or spine) | 2 | 20 |

| IT chemotherapy | 1 | 10 |

| RT + IT chemotherapy | 3 | 30 |

| Surgery + RT | 1 | 10 |

| Post-CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| RT after CAR T-cell therapy | 2 | 20 |

| None (due to recent DCEP chemotherapy) | 1 | 10 |

| No. of days between last RT session and CAR T-cell infusion | ||

| Median (range) | 14.5 (9-39) | |

| Systemic bridging therapy‡ | ||

| mCBAD | 1 | 10 |

| KCd (±RT) | 2 | 20 |

| Vd (±revlimid ± RT) | 2 | 20 |

| DCEP (±RT) | 2 | 20 |

| PXd (+RT) | 1 | 10 |

| VD-CE (+IT chemotherapy and RT) | 1 | 10 |

| Dara-Pom-Dex+Seli (+IT chemotherapy and RT) | 1 | 10 |

| Treated vs untreated known CNS disease at time of LDC (n = 8)§ | ||

| Treated | 7/8 | 87.5 |

| Untreated | 1/8 | 12.5 |

| CAR T-cell product | ||

| Ide-cel | 6 | 60 |

| Cilta-cel | 4 | 40 |

| CAR T-cell dose | ||

| Ide-cel median (range) million cells | 427 (154-447) | |

| Cilta-cel | ||

| Median (range) dose, ×106 CAR+ per kg | 0.7 (0.6-0.7) | |

| Median (range) million cells | 54 (47-61) | |

| CAR T-cell manufacturing | ||

| Out-of-specification products | 0 | 0 |

| Successful manufacturing on first attempt | 9 | 90 |

| Successful manufacturing on second attempt | 1 | 10 |

| Lymphodepletion received before CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| Fludarabine and cyclophosphamide | 10 | 100 |

| Treatments after CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| CNS-directed RT | 2 | 20 |

| For 2 patients with CNS disease diagnosed after CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| In one of them this was followed by Elo-Pom-Dex, VD-AC, and teclistamab | ||

| Pomalidomide-based therapy | ||

| Daratumumab-pomalidomide-dexamethasone | 1 | 10 |

| Selinexor-pomalidomide-dexamethasone ± IT chemotherapy ± RT | 2 | 20 |

| Isatuximab-carfilzomib-dexamethasone | 2 | 20 |

| BCMA-directed bispecific therapy (teclistamab) | 1 | 10 |

| None or N/A | 2 | 20 |

Dara PXd, Daratumumab Pomalidomide Selinexor Dexamethasone; Dara-Pom-Dex+Seli; Daratumumab, Pomalidomide, Dexamethasone, Selinexor; DCEP, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and cisplatin; Elo-Pom-Dex, Elotuzumab, Pomalidomide, Dexamethasone; KCd, carfilzomib cyclophosphamide dexamethasone; LDC, lymphodepleting chemotherapy; mCBAD, modified dosing cyclophosphamide bortezomib doxorubicin dexamethasone; N/A, not available; PXd, pomalidomide selinexor dexamethasone; RT, radiotherapy; Vd, bortezomib-dexamethasone; VD-AC, bortezomib-dexamethasone-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide; VD-CE: bortezomib-dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide-etoposide.

For those 2 patients, CNS disease was diagnosed at days 11 and 14 after CAR T-cell therapy.

IT chemotherapy varied per institutional preference and included either IT cytarabine or IT methotrexate.

Systemic bridging therapies included mCBAD, KCd, Vd, DCEP, PXd, VD-CE, VD-AC, Dara-PXd, and RT.

Of 10 patients, 8 had known CNS disease before CAR T-cell therapy, of which 7 received CNS disease–directed therapy before CAR T-cell infusion. Two patients had their CNS disease discovered after CAR T-cell therapy so did not receive CNS-directed therapy before CAR T-cell therapy but did receive RT after CAR T-cell therapy.

The median duration between the diagnosis of CNS myelomatous involvement and CAR T-cell therapy was 53 days (range, 21-710). The time between CNS diagnosis and CAR T-cell therapy was ≤60 days in 5 patients and >300 days in 3 patients. Two patients had their CNS disease diagnosed within 14 days after CAR T-cell infusion (days 11 and 14) and subsequently underwent post–CAR T-cell radiotherapy (RT). Those 2 patients were included in our study because their CNS disease was diagnosed within the window of CRS/ICANS and, with the lack of pre-CAR T-cell brain imaging, were thought to most likely have had their CNS disease within the preceding few weeks. The 3 patients who exhibited CNS involvement that started >300 days before CAR T-cell infusion continued to have active CNS disease before CAR T-cell therapy, requiring CNS-directed therapy during bridging (Table 2).

Treatments

There were no significant issues encountered during CAR T-cell manufacturing for the majority of patients, with 9 patients (90%) having a successful first manufacturing attempt and 1 patient (10%) having a successful second manufacturing attempt. Notably, this patient had required heavy treatment with intense chemotherapy, including cyclophosphamide, before CAR T-cell therapy. All patients received a CAR T-cell therapy product that met manufacturer specifications. All patients received standard-of-care fludarabine and cyclophosphamide as lymphodepletion before CAR T-cell therapy.

Seven patients (70%) received CNS-directed therapy (CNS-Tx) as part of bridging before lymphodepleting chemotherapy as follows: 2 patients received RT alone, 3 received RT plus IT chemotherapy, 1 received IT chemotherapy only, and 1 received surgery plus RT (Table 2). IT chemotherapy varied per institutional preference and included either IT cytarabine or IT methotrexate. The median duration between the last dose of RT and CAR T-cell infusion was 14.5 days (range, 9- 39). Conversely, 3 patients (30%) did not receive CNS-Tx as part of bridging for the following reasons: 2 were diagnosed within 14 days after CAR T-cell therapy and received subsequent RT; and 1 had recent DCEP (dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and cisplatin) chemotherapy.

Systemic bridging therapies varied widely in the form of the following regimens: mCBAD (modified dosing cyclophosphamide-bortezomib-doxorubicin-dexamethasone; n = 1); KCd (carfilzomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone) ± RT (n = 2); bortezomib-dexamethasone ± revlimid ± RT (n = 2); DCEP ± RT (n = 2); PXd (pomalidomide-selinexor-dexamethasone) + RT (n = 1); VD-CE (bortezomib-dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide-etoposide) + IT chemotherapy + RT (n = 1); and Dara-PXd (daratumumab-PXd) + IT chemotherapy + RT (n = 1; Table 2).

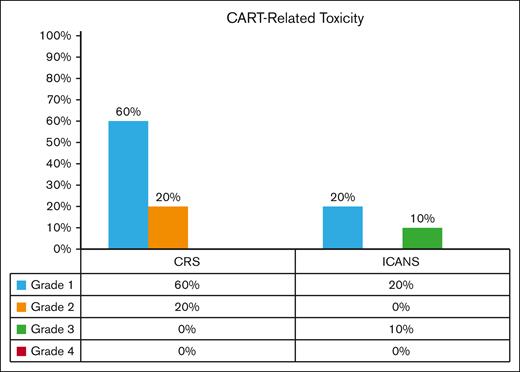

Safety

Most patients had grade 1 to 2 CRS (80%), and none had severe CRS (grade ≥3). Two patients (20%) had grade 1 ICANS; 1 patient (10%) had grade 3 ICANS; and none had grade 4 ICANS (Figure 1). Two patients experienced delayed neurotoxicity after ide-cel: 1 with delayed lethargy that was treated with steroids; and the other with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy due to JC virus, which was treated with steroids plus pembrolizumab,17 with an initial response followed by relapse, for which he received investigational therapy on a clinical trial and achieved partial response (PR). Notably, none exhibited delayed parkinsonian side effects (Table 3).

BCMA CAR T-cell therapy recipients with CRS and ICANS. CRS grade 1 and 2 were 60% and 20%, respectively. No grade 3 to 4 CRS was observed. ICANS grade 1 and 3 were 20% and 10%, respectively, all of which reversed. No grade 4 ICANS was observed.

BCMA CAR T-cell therapy recipients with CRS and ICANS. CRS grade 1 and 2 were 60% and 20%, respectively. No grade 3 to 4 CRS was observed. ICANS grade 1 and 3 were 20% and 10%, respectively, all of which reversed. No grade 4 ICANS was observed.

Toxicities

| Characteristic . | Value (n = 10) . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicities | ||

| Maximum grade CRS | ||

| 0 | 2 | 20 |

| 1 | 6 | 60 |

| 2 | 2 | 20 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Maximum grade ICANS | ||

| 0 | 7 | 70 |

| 1 | 2 | 20 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 10 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| HLH | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 10 | 100 |

| Tocilizumab | ||

| Yes | 5 | 50 |

| No | 5 | 50 |

| Steroid use | ||

| Yes | 5 | 50 |

| No | 5 | 50 |

| Anakinra | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 10 | 100 |

| Delayed Parkinsonian neurotoxicity | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 10 | 100 |

| Delayed non-Parkinsonian neurotoxicity | ||

| Yes∗ | 2 | 20 |

| No | 8 | 80 |

| Treatment of delayed neurotoxicity | ||

| Steroids | 1 | 10 |

| Steroids followed by pembrolizumab (PML due to JC virus),17 followed by investigational therapy on clinical trial | 1 | 10 |

| Infections | ||

| Yes | 5 | 50 |

| No | 5 | 50 |

| Characteristic . | Value (n = 10) . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicities | ||

| Maximum grade CRS | ||

| 0 | 2 | 20 |

| 1 | 6 | 60 |

| 2 | 2 | 20 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Maximum grade ICANS | ||

| 0 | 7 | 70 |

| 1 | 2 | 20 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 10 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| HLH | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 10 | 100 |

| Tocilizumab | ||

| Yes | 5 | 50 |

| No | 5 | 50 |

| Steroid use | ||

| Yes | 5 | 50 |

| No | 5 | 50 |

| Anakinra | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 10 | 100 |

| Delayed Parkinsonian neurotoxicity | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 10 | 100 |

| Delayed non-Parkinsonian neurotoxicity | ||

| Yes∗ | 2 | 20 |

| No | 8 | 80 |

| Treatment of delayed neurotoxicity | ||

| Steroids | 1 | 10 |

| Steroids followed by pembrolizumab (PML due to JC virus),17 followed by investigational therapy on clinical trial | 1 | 10 |

| Infections | ||

| Yes | 5 | 50 |

| No | 5 | 50 |

HLH, Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; PML, Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy.

One patient had delayed lethargy and another patient had progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Refer to text regarding their management and outcome.

Cytopenias were common as would be expected after CAR T-cell therapy. At day 90, 6 patients (60%) had some degree of cytopenia, with severity as follows: 3 (30%) had absolute neutrophil count <1 x 103/μL; 2 (20%) had hemoglobin <8 g/dL; and 4 (40%) had platelets <50 x 103/μL. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) and Thrombopoietin (TPO) agonists were ongoing in 7 patients (70%) and 2 patients (20%), respectively, by day 90. None of the patients required utilization of a stem cell boost.

After CAR T-cell therapy, infections developed in 5 patients (50%), including 1 with cytomegalovirus viremia and Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6) viremia, 1 with adenovirus and norovirus infection, 2 with bacterial infections, and 1 with clostridium difficile infection. They were all successfully managed, with 1 patient requiring intensive care unit admission. At follow-up beyond 6 months, 1 patient who achieved complete response (CR) developed fatal sepsis without disease progression.

Responses, survival, and nonrelapse mortality

After systemic bridging therapy, the majority of patients had either progressive disease (n = 3) or stable disease (n = 3), with only 2 patients with PR, 1 patient with very good PR, and 1 patient with CR. After CAR T-cell therapy, the best responses achieved were an ORR of 80%, which included 60% CR/stringent complete response (sCR), 10% very good PR, and 10% PR (Table 4). The best response was achieved by day 30 in 5 patients (50%), by day 90 in 2 patients (20%), and by 6 months in 2 patients (20%), whereas 1 patient (10%) had progressive disease (PD) by day 30. The MRD response assessment showed that 4 patients (40%) achieved MRD negativity within the first 90 days after CAR T-cell infusion. Systemic response in the 2 patients who had their CNS disease treated after CAR T-cell therapy was CR and PD. All patients were evaluable for CNS responses by day 90, with a 100% CNS response rate, defined by improvement of imaging findings and/or clearance of CSF involvement.

Response outcomes and manner of progression after CAR T-cell therapy

| Response . | Value (n = 10) . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Best systemic response | ||

| ORR | 8 | 80 |

| CR/sCR | 6 | 60 |

| VGPR | 1 | 10 |

| PR | 1 | 10 |

| SD | 1 | 10 |

| PD | 1 | 10 |

| Best MRD response | ||

| MRD negative | 4 | 40 |

| MRD positive | 2 | 20 |

| Not tested | 4 | 40 |

| CNS response by day 90 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 |

| Manner of progression after CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| CNS progression∗ | 4 | 40 |

| Systemic progression | 8 | 80 |

| Manner of identification of progression | ||

| Asymptomatic† | 5 | 50 |

| Symptomatic | 5 | 50 |

| Response . | Value (n = 10) . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Best systemic response | ||

| ORR | 8 | 80 |

| CR/sCR | 6 | 60 |

| VGPR | 1 | 10 |

| PR | 1 | 10 |

| SD | 1 | 10 |

| PD | 1 | 10 |

| Best MRD response | ||

| MRD negative | 4 | 40 |

| MRD positive | 2 | 20 |

| Not tested | 4 | 40 |

| CNS response by day 90 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 |

| Manner of progression after CAR T-cell therapy | ||

| CNS progression∗ | 4 | 40 |

| Systemic progression | 8 | 80 |

| Manner of identification of progression | ||

| Asymptomatic† | 5 | 50 |

| Symptomatic | 5 | 50 |

PD, progressive disease; sCR, stringent complete respo; SD, stable disease; VGPR, very good PR.

Patients who had CNS progression after initial CNS response.

Asymptomatic patients for whom progression was identified on routine testing.

With a median follow-up of 381 days after CAR T-cell infusion, for patients diagnosed with CNS myeloma before CAR T-cell infusion (n = 8), the median PFS was 6.3 months (95% confidence interval, 1.9-10.7), and PFS at 6 months was 62.5%. The median OS was 13.3 months, whereas at 6 months and 1 year, the OS was 87.5% and 75%, respectively (Figure 2). For the entire cohort, including those with CNS myeloma identified before and after CAR T-cell therapy (n = 10), PFS analysis was not conducted because PFS was not calculable for 2 patients who were diagnosed with CNS myeloma after CAR T-cell therapy, but OS analysis showed similar outcomes with a median OS of 13.5 months (95% confidence interval, 6.0-21.1), OS at 6 months of 90%, and OS at 1 year of 70% (Figure 2). Notably, for 2 patients who had their CNS identified shortly after CAR T-cell infusion, 1 patient achieved sustained CR but unfortunately had nonrelapse mortality from sepsis at 6.3 months after returning to his home country outside the United States. The second patient had early systemic progression/refractoriness by day 30, an initial CNS disease response followed by CNS progression, and died 13.5 months after CAR T-cell infusion. Table 4 describes the manner of progression after CAR T-cell therapy, in which 80% had systemic progression, and 40% had CNS progression. Notably, patients who had a response to bridging (n = 4) had better outcomes after CAR T-cell therapy, as outlined in Table 5. All 4 patients achieved CR within 6 months, had a CNS response, and had relatively better survival than the rest of the cohort, with the exception of 1 patient who died without relapse at 6.3 months from fatal sepsis.

PFS and OS for patients with MM with CNS involvement treated with CAR T-cell therapy. (A) PFS analysis of patients diagnosed with CNS myeloma before CAR T-cell therapy (n = 8): the median PFS was 6.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9-10.7), and PFS at 6 months was 62.5%. PFS was not calculable for the 2 patients who were diagnosed with CNS myeloma after CAR T-cell therapy, so they were excluded from this analysis. (B) OS analysis. (Bi) OS of patients diagnosed with CNS myeloma before CAR T-cell therapy (n = 8): the median OS was 13.3 months; OS at 6 months and 1 year was 87.5% and 75%, respectively. (Bii) OS of patients with CNS myeloma diagnosed before CAR T-cell therapy or after CAR T-cell therapy (n = 10): the median OS was 13.5 months (95% CI, 6.0-21.1); OS at 6 months and 1 year was 90% and 70%, respectively.

PFS and OS for patients with MM with CNS involvement treated with CAR T-cell therapy. (A) PFS analysis of patients diagnosed with CNS myeloma before CAR T-cell therapy (n = 8): the median PFS was 6.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9-10.7), and PFS at 6 months was 62.5%. PFS was not calculable for the 2 patients who were diagnosed with CNS myeloma after CAR T-cell therapy, so they were excluded from this analysis. (B) OS analysis. (Bi) OS of patients diagnosed with CNS myeloma before CAR T-cell therapy (n = 8): the median OS was 13.3 months; OS at 6 months and 1 year was 87.5% and 75%, respectively. (Bii) OS of patients with CNS myeloma diagnosed before CAR T-cell therapy or after CAR T-cell therapy (n = 10): the median OS was 13.5 months (95% CI, 6.0-21.1); OS at 6 months and 1 year was 90% and 70%, respectively.

Outcomes of patients who responded to bridging therapy

| Response to bridging . | Patient number . | Systemic response . | CNS response . | PFS, mo . | OS, mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | Patient 10 | CR (day 30) | Yes (day 30) | 9.7 | 12.1 |

| VGPR | Patient 7 | VGPR (day 30) sCR (6 mo) | Yes (day 30) | 6.3 | 13.3 |

| PR | Patient 8 | VGPR (day 30) sCR (6 mo) | Yes (day 30) | 8 | 33.4 |

| PR | Patient 2 | CR (day 30) | Yes (day 90)∗ | 6.3† | 6.3† |

| Response to bridging . | Patient number . | Systemic response . | CNS response . | PFS, mo . | OS, mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | Patient 10 | CR (day 30) | Yes (day 30) | 9.7 | 12.1 |

| VGPR | Patient 7 | VGPR (day 30) sCR (6 mo) | Yes (day 30) | 6.3 | 13.3 |

| PR | Patient 8 | VGPR (day 30) sCR (6 mo) | Yes (day 30) | 8 | 33.4 |

| PR | Patient 2 | CR (day 30) | Yes (day 90)∗ | 6.3† | 6.3† |

First CNS response assessment after CAR T-cell therapy was done at day 90, with no available data at day 30.

Patient achieved CR but died without progression at 6.3 months due to fatal sepsis.

Discussion

Our study evaluated the use of CAR T-cell therapy in patients with MM with CNS involvement. Previously, theoretical concerns about exacerbation of immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity may have prevented clinicians from considering CAR T-cell therapy for patients with CNS involvement. However, our findings demonstrated that BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy is indeed feasible in this patient population without encountering excessive neurotoxicity. These early data suggest that CNS myeloma should not be a barrier to considering CAR T-cell therapy as a treatment option for eligible patients.

In our study, the majority of patients (80%) had grade 1/2 CRS, and there was no observed incidence of grade ≥3 CRS. The rates of ICANS were also not in excess, with 20% having grade 1 and 10% having grade 3 ICANS. Two patients experienced delayed but treatable neurotoxicity (excessive fatigue and Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy [PML] due to JC virus) after ide-cel, with no reported parkinsonian side effects. These outcomes are consistent with those observed in clinical trials and real-world outcomes (RWOs). For patients with MM without CNS involvement who received ide-cel in the KarMMa-1 and KarMMa-3 clinical trials, CRS rates ranged from 84% to 88%, with 5% classified as grade ≥3, and ICANS/neurotoxicity rates were between 15% and 18%, with 3% classified as grade ≥3.5,18 Similarly, for cilta-cel, patients with MM without CNS involvement in the CARTITUDE-1 trial had CRS rates of 95%, with 4% classified as grade ≥3, and ICANS/neurotoxicity rates of 21%, with 9% classified as grade ≥3.6 In the real-world setting, patients with MM who received ide-cel had CRS rates of 81% to 82%, with 3% to 4% having grade ≥3, and ICANs/neurotoxicity rates of 15% to 27%, with 4% to 5% having grade ≥3.19,20 RWOs for patients treated with cilta-cel showed CRS rates of 81%, with 7% as grade ≥3, and ICANS/neurotoxicity rates of 22%, with 8% as grade ≥3.21 Delayed neurotoxicity occurred in 9% in the form of cranial nerve palsy, parkinsonism, and others.21 With the caveat of cross-study comparisons, our CRS and ICANS outcomes appear to be similar to those reported in clinical trials and RWOs, suggesting that there is no evidence of excess neurotoxicity/ICANS or CRS with this approach.

Additionally, our study demonstrated an ORR of 80%, which aligns with reported outcomes of both ide-cel and cilta-cel in clinical trials and RWO studies. In the KarMMa-1 and KarMMa-3 trials, ide-cel showed an ORR of 71% to 73%, whereas cilta-cel in the CARTITUDE-1 trial demonstrated an ORR of 97%. RWO data indicated ORRs of 71% and 80% (including expanded access protocol) for ide-cel and cilta-cel, respectively.19,21 Remarkably, 100% of our patient cohort achieved a CNS response by day 90. However, it is worth noting that this is reflective of both the CNS-directed therapy received during bridging and possibly the CAR T-cell therapy itself. Given the retrospective nature of our study, we cannot determine which intervention had the most significant impact on achieving CNS response. Remarkably, patients who had a response to bridging therapy (Table 5) seem to have had better outcomes than the rest of the cohort. All 4 patients achieved CR within 6 months, had a CNS response, and had relatively better survival, except 1 patient who died without progression at 6.3 months. This highlights that optimizing bridging before CAR T-cell therapy may be key to achieving better outcomes after infusion (Table 5).

Despite the initial excellent outcomes of this approach in terms of 100% CNS response rate and 80% ORR, the durability of response was relatively short, with a median PFS and OS of 6.3 and 13.3 months, respectively, which is reflective of the aggressive nature of this disease entity. As a future direction, in our opinion, this may suggest exploring maintenance therapies after CAR T-cell therapy when this approach is implemented. There are currently limited data on what the optimal maintenance therapy may be; however, the choice of maintenance therapy will likely need to be tailored for each patient depending on prior therapies received. Candidates for such therapies include immunomodulatory agents such as pomalidomide or CELMoDs when available.22,23 It may also be feasible to pursue sustained BCMA targeting after CAR T-cell therapy, with agents such as bispecific T-cell engagers or belantamab mafodotin. Early data suggest both can be used for post–BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy relapse24 and are currently being explored in clinical trials for use as maintenance after autologous stem cell transplantation.25-30 In addition, belantamab mafodotin is being specifically evaluated in a clinical trial for use as maintenance after BCMA CAR T-cell therapy.31 Results of those ongoing clinical trials may provide insights into which maintenance strategy would be the most feasible. Although our study’s limited sample size precludes definitive conclusions, our study suggests that the preferred sequence of management would be to incorporate CNS-directed therapy, including radiotherapy (RT) and IT chemotherapy, during bridging therapy before CAR T-cell infusion. In our study, the median number of days between the last session of RT and CAR T-cell therapy was 14.5 days (range, 9-39). Our data suggest that it may be beneficial to screen for CNS myeloma in HR individuals, followed by CNS-directed therapy before CAR T-cell therapy. In our cohort, 60% had non-CNS EMD, and 30% had para-medullary EMD, which is consistent with prior studies that showed extensive EMD may pose a risk factor for developing CNS myeloma.32 Other risk factors may include plasma cell leukemia, plasmablastic morphology, bulky tumor burden, new neurological symptoms, and a history of prior CNS disease.32 We suggest that patients with those risk factors could be considered HR for CNS myeloma, for whom incorporating imaging and/or CSF evaluation in the pre-CAR T-cell workup may be warranted.

Importantly, most patients (90%) successfully had their CAR T-cell product manufactured on the first attempt. One patient with a manufacturing failure on first attempt had successful manufacturing with the second attempt, and there were no nonconforming products. Upon careful review of this patient’s disease and treatment characteristics, the only factor identified that could have contributed to the manufacturing challenges is that he was heavily treated with intense chemotherapy, including cyclophosphamide (DCEP followed by ixazomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone), before CAR T-cell therapy. It is also worth mentioning that during that period the manufacturing challenges were relatively high for cilta-cel, which is the product that this patient received.

The pathophysiology underlying the rare but serious movement and neurocognitive toxicities underlying BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy is not fully understood.33 Few data have suggested that neurocognitive and hypokinetic movement disorders with features of parkinsonism can rarely occur after BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy and may be linked to BCMA expression on the healthy neural tissue within the basal ganglia and caudate, representing an on-target, off-tumor effect.8,9,34 Our data suggest that BCMA targeting of CNS myeloma tumor cells does not appear to increase this risk. Together, these may suggest that, if implicated, it is the excessive BCMA expression on healthy neural tissue within the CNS and not the BCMA expression on tumor cells that may be implicated. Further correlative studies are necessary for a deeper understanding and evaluation.

Our study has several limitations, including its retrospective nature, variability of data and methods used per the different institutional guidelines, variation in MRD testing techniques, and lack of correlative laboratory data. Our study has a small sample size; however, given the rarity of patients with CNS myeloma involvement who go on to receive CAR T-cell therapy successfully, we believe it provides valuable practice-informing insights, including the feasibility of this approach without excess toxicity. Furthermore, although not addressed in our study, previous research on different CAR T-cell products in lymphoma with CNS involvement has demonstrated the ability of these products to cross into the CSF without causing excess neurotoxicity.10

In conclusion, this study suggests that BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy, either ide-cel or cilta-cel, in patients with MM and CNS involvement is safe and feasible, with a 100% CNS response rate. Screening for CNS involvement in patients at HR could be considered before CAR T-cell therapy, to allow for CNS-directed therapy during the bridging period. Additionally, optimizing bridging therapy may be key to improve outcomes after CAR T-cell therapy. Despite the initial excellent ORR, PFS was relatively short, suggesting that maintenance strategies after CAR T-cell therapy in this patient population could be explored. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Authorship

Contributions: M.R.G. contributed to project development, data preparation, statistical analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript writing; D.K.H. and K.K.P. contributed to project development, supervision, study design, interpretation of data, and manuscript writing; and O.C.P., A. Cohen, D.V., A. Chung, C.J.F., and P.V. contributed to data contribution from participating cancer centers, critical review of the manuscript, and editing the final draft.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.R.G. reports consulting or advisory role fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Boxer Capital LLC, and Arcellx. O.C.P. reports consulting or advisory role fees from Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene/Juno and Legend Biotech. A. Cohen reports consulting or advisory role fees from AbbVie, Arcellx, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Ichnos Sciences, ITeos Therapeutics, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, and Takeda; research funding from Genentech/Roche (institutional), GlaxoSmithKline (institutional), Janssen Oncology (institutional), and Novartis (institutional); patents, royalties, other intellectual property with patents related to CAR T cells and biomarkers of cytokine release syndrome; and travel, accommodations, and expenses paid by AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ichnos Sciences, and Janssen Oncology. D.V. reports consulting or advisory role fees from Celgene, CSL Behring, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Oncopeptides, Sanofi, and Takeda; research funding from Active Biotech (institutional) and Takeda (institutional); and travel, accommodations, and expenses paid by Karyopharm Therapeutics and Takeda. A. Chung reports consulting or advisory role fees from Janssen; and research funding from AbbVie (institutional), Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene (institutional), Caelum Biosciences (institutional), Cellectis (institutional), Janssen (institutional), k36 Therapeutics (institutional), and Merck (institutional). C.J.F. reports stock and other ownership interests in Affimed (AFMD). P.V. reports consulting or advisory role fees from AbbVie/Genentech, Bristol Myers Squibb (Mexico), GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Sanofi; research funding from AbbVie (institutional), GlaxoSmithKline (institutional), Janssen (institutional), and Teneobio (institutional); travel, accommodations, and expenses from Sanofi; and uncompensated relationships with GlaxoSmithKline. D.K.H. reports consulting or advisory role fees from Bristol Myers Squibb; and research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene. K.K.P. reports consulting or advisory role fees from AbbVie, Arcellx, Bristol Myers Squibb, Caribou Biosciences, Celgene, Cellectis, Janssen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Merck, Pfizer, and Takeda; research funding from AbbVie/Genentech, Allogene Therapeutics, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellectis, Janssen, Nektar, Precision Biosciences, and Takeda; and travel, accommodations, and expenses from Bristol Myers Squibb.

Correspondence: Krina K. Patel, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Department of Lymphoma and Myeloma, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030; email: kpatel1@mdanderson.org.

References

Author notes

The underlying data that support the results in this manuscript are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Krina K. Patel (kpatel1@mdanderson.org).

![PFS and OS for patients with MM with CNS involvement treated with CAR T-cell therapy. (A) PFS analysis of patients diagnosed with CNS myeloma before CAR T-cell therapy (n = 8): the median PFS was 6.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9-10.7), and PFS at 6 months was 62.5%. PFS was not calculable for the 2 patients who were diagnosed with CNS myeloma after CAR T-cell therapy, so they were excluded from this analysis. (B) OS analysis. (Bi) OS of patients diagnosed with CNS myeloma before CAR T-cell therapy (n = 8): the median OS was 13.3 months; OS at 6 months and 1 year was 87.5% and 75%, respectively. (Bii) OS of patients with CNS myeloma diagnosed before CAR T-cell therapy or after CAR T-cell therapy (n = 10): the median OS was 13.5 months (95% CI, 6.0-21.1); OS at 6 months and 1 year was 90% and 70%, respectively.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/5/10.1182_bloodadvances.2024014345/5/m_blooda_adv-2024-014345-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1763473283&Signature=RI76qzJbKss8kPfBIIlguwD91otPU~FZT420x4fKiJ3EhilX9C~DKJZKlO2z3-RNm4Rly-8SxlL8uhe7Yo3mwA9PuzIDwm0gYh3WD0kH8jSAxHiKNLML7OI562Xd0xN9j7enj3d760koqT2HiGbHnq484uRe2JePCENrKLXgrspbVUms9KZeitRfFmghsZCPH7IZts33b~5r0yZxOLSkKUfkAYo~QUEEIo2ac12KotsabJ2gkNNe3S7niiI-8HZUdQpeTitnaPFBlGu0FK1LYBQZJO23O44bxN~QZfVMoAXteHch2l49esHi~F5RbrL2BsjCDChDyHbj5-xwNID0Vg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)