Key Points

ICI before allogeneic transplantation in Hodgkin lymphoma improves OS when compared with chemotherapy (no-ICI).

ICI increases the risk of grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD, which may be abrogated by increasing immunosuppression.

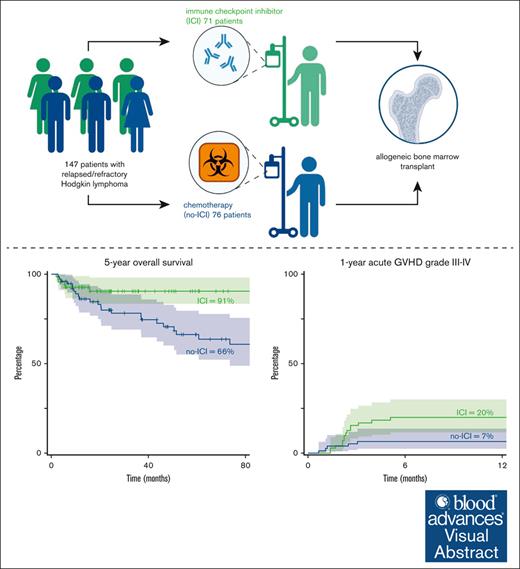

Visual Abstract

Patients with relapsed classic Hodgkin lymphomas (cHLs) receive salvage therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) or chemotherapy (no-ICI). Patients responding to therapy often undergo consolidation with allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation (alloBMT). We previously reported that relapsed patients with cHL treated with ICI followed by alloBMT experienced improved 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) compared with patients treated with salvage chemotherapy without ICI followed by alloBMT. In this retrospective analysis, we report the 5-year overall survival (OS), PFS, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) incidence in patients with cHL treated with ICI before alloBMT with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide GVHD prophylaxis. Among the 147 relapsed/refractory patients with cHL, 71 (48.3%) received ICIs and 76 (51.7%) received chemotherapy without ICIs (no-ICI) before alloBMT. We observed an improved 5-year estimated OS of 91% (ICI) vs 66% (no-ICI; hazard ratio [HR], 0.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16-0.98; P = .046) and a 5-year estimated PFS of 84% (ICI) vs 53% (no-ICI; HR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.2-0.81; P = .011). The 12-month cumulative incidence of grade 3 to 4 GVHD was 20% (ICI) and 7% (no-ICI; subdistribution hazard ratio (SDHR), 3.16; 95% CI, 1.13-8.81; P = .03). More frequent grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD was likely due to the higher incidence of grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD in the subset of patients with pretransplant exposure to ICI and shortened duration (60 days) of immunosuppression vs patients with long immunosuppression (day 180). These data suggest that patients with cHL treated with ICI and alloBMT experience improved OS, and the GVHD risk can be mitigated by immunosuppression until day 180.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, are associated with high response rates in patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL).1,2 Patients responding to ICI often undergo consolidation with an autologous3 or allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation (BMT; alloBMT).4,5 alloBMT carries significant and well-recognized risks of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and treatment-related mortality. It is also now well recognized that prior ICI treatment increases morbidity and mortality, particularly GVHD, associated with alloBMT.6,7 Even before posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) became the standard of care for GVHD prophylaxis after alloBMT,8 it was recognized that PTCy appeared to decrease GVHD, particularly in the setting of pretransplant ICI therapy.4,7 Our previous report demonstrated that patients with cHL who received ICIs before alloBMT with PTCy prophylaxis experienced improved 3-year progression-free survival (PFS), with limited toxicity, compared with salvage chemotherapy without ICI before alloBMT.5 However, the short duration of follow-up was inadequate to ascertain differences in overall survival (OS). Hence, an updated analysis of the long-term survival of patients with cHL undergoing alloBMT is warranted. Here, we report alloBMT outcomes of 147 patients with R/R cHL receiving ICI or chemotherapy before alloBMT with PTCy at the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center (SKCCC).

Methods

Patients

After Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board approval, we queried the SKCCC transplantation database for patients with cHL who received nonmyeloablative (NMA) conditioning alloBMT with PTCy GVHD prophylaxis between November 2004 and August 2023. We reviewed medical records including clinical notes and pathology, radiology, and laboratory reports. Data were locked in December 2023. The decision for salvage therapy with ICI or with chemotherapy and the decision for alloBMT treatment were at the discretion of the treating physician and patient. AlloBMT was generally preferred for patients with either primary refractory disease or first remission lasting <12 months or patients failing prior autologous transplantations.

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board.

alloBMT with PTCy

Patients undergoing NMA alloBMT at Johns Hopkins receive conditioning with 30 mg/m2 fludarabine IV on days –6 through –2, cyclophosphamide 14.5 mg/kg IV on days –6 and –5, and total body irradiation as a single fraction at a dose of 200 cGy on day –1. Three patients received conditioning with pentostatin and low-dose cyclophosphamide along with total body irradiation as a single fraction at a dose of 400 cGy on day –1 during fludarabine shortage. Donors underwent bone marrow harvest on day 0 or peripheral blood mobilization by subcutaneous granulocyte stimulating factor at 10 mg/kg per day for 5 days. Patients received PTCy (IV 50 mg/kg per day) on days +3 and +4, along with mycophenolate mofetil between days +5 and +35 and tacrolimus or sirolimus between days +5 and +180 (n = 83 patients) or between days +5 and +60 (n = 64 patients), for GVHD prophylaxis. GVHD was treated per institutional guidelines and as described before.9-12 Our review did include patients receiving alloBMT as part of research protocols or standard of care. T-cell chimerism was obtained at day +60.

Disease status and clinical outcome definitions

OS was calculated as the time from alloBMT until death, with censoring at the last follow-up date. Similarly, PFS was calculated as the time from alloBMT to disease relapse/progression or death, with censoring at the last follow-up date for relapse-free patients. Nonrelapse mortality (NRM) was defined as death from causes not related to disease relapse. NRM was a competing event when estimating the cumulative incidence (CuI) of relapse and vice versa. Relapse, graft failure, and death were competing events for CuI of acute GVHD (aGVHD) and chronic GVHD (cGVHD). Neutrophil and platelet recovery time was the interval between allograft infusion and the first of 3 consecutive days with neutrophils >0.5 ×103/μL and the first of 3 consecutive days with platelets >20 ×103/μL, respectively. Patients were classified as donor T-cell engrafted if ≥5% donor cells were detected after day +60. Engraftment failure was defined as <5% donor chimerism at any point beyond day +60. In engrafted patients, full engraftment was defined as ≥95% donor T cells, whereas ≥5% to 94% donor T cells were designated mixed chimeras. Modified Keystone criteria and National Institutes of Health Consensus Criteria were used to diagnose and score aGVHD and cGVHD.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics and clinical variables were summarized via descriptive statistics. Median follow-up was reported using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. OS, PFS, and median follow-up are reported using the Kaplan-Meier estimator. The CuI of aGVHD and cGVHD, relapse, and NRM outcomes are assessed with the proportional subdistribution hazard regression model for competing risks. Statistical analyses are performed using R version 4.3.1.

Results

Patient and alloBMT characteristics

From November 2004 to August 2023, a total of 147 consecutive relapsed patients with cHL underwent alloBMT at SKCCC, and the alloBMT characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Seventy-one patients (48.3%) received ICIs; the characteristics are summarized in supplemental Table 1. Seventy-six patients (51.7%) received chemotherapy without ICIs before alloBMT. ICI patients received a median of 3 lines of treatments (range, 2-13). Patients receiving chemotherapy without ICI (no-ICI) also received a median of 3 lines of treatments (range, 1-7). Within the ICI cohort, 47 patients (66.2%) received ICI as the last therapy before alloBMT, whereas the remaining patients received additional therapy before alloBMT. At the time of alloBMT, 32 patients (45%) and 37 patients (52%) were in complete remission (CR) and partial remission in the ICI cohort, respectively, whereas 41 (54%) and 22 patients (29%) were in CR and partial remission in the no-ICI cohort, respectively. Forty-eight patients (68%) in the ICI subgroup and 70 patients (92%) in the no-ICI subgroup received alloBMT from haploidentical donors.

Patient characteristics

| . | ICIs . | No-ICIs . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 71 (48.3) | 76 (51.7) | |

| Median age at alloBMT (IQR), y | 32 (26-40) | 36 (28-45) | P = .2 |

| Sex, n (%) | P = .8 | ||

| Male | 39 (55) | 40 (53) | |

| Female | 32 (45) | 36 (47) | |

| Median prior treatments, n (range) | 3 (2-13) | 3 (1-7) | P = .4 |

| ICI as the last therapy before, n (%) | 47 (66.2) | N/A | |

| Median time from ICI to alloBMT (IQR), d | 61 (43-145) | N/A | |

| Ann Arbor stage at diagnosis, n (%) | P = .2 | ||

| Stage I-II | 28 (39%) | 38 (50%) | |

| Stage III-IV | 43 (61%) | 38 (50%) | |

| Prior ASCT | 12 (17%) | 27 (35%) | |

| Pre-alloBMT remission status, n (%) | P = .02 | ||

| CR | 32 (45%) | 41 (54%) | |

| Partial remission | 37 (52%) | 22 (29%) | |

| Stable disease | 2 (3%) | 13 (17%) |

| . | ICIs . | No-ICIs . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 71 (48.3) | 76 (51.7) | |

| Median age at alloBMT (IQR), y | 32 (26-40) | 36 (28-45) | P = .2 |

| Sex, n (%) | P = .8 | ||

| Male | 39 (55) | 40 (53) | |

| Female | 32 (45) | 36 (47) | |

| Median prior treatments, n (range) | 3 (2-13) | 3 (1-7) | P = .4 |

| ICI as the last therapy before, n (%) | 47 (66.2) | N/A | |

| Median time from ICI to alloBMT (IQR), d | 61 (43-145) | N/A | |

| Ann Arbor stage at diagnosis, n (%) | P = .2 | ||

| Stage I-II | 28 (39%) | 38 (50%) | |

| Stage III-IV | 43 (61%) | 38 (50%) | |

| Prior ASCT | 12 (17%) | 27 (35%) | |

| Pre-alloBMT remission status, n (%) | P = .02 | ||

| CR | 32 (45%) | 41 (54%) | |

| Partial remission | 37 (52%) | 22 (29%) | |

| Stable disease | 2 (3%) | 13 (17%) |

IQR, interquartile range; N/A, not applicable.

Engraftment and GVHD

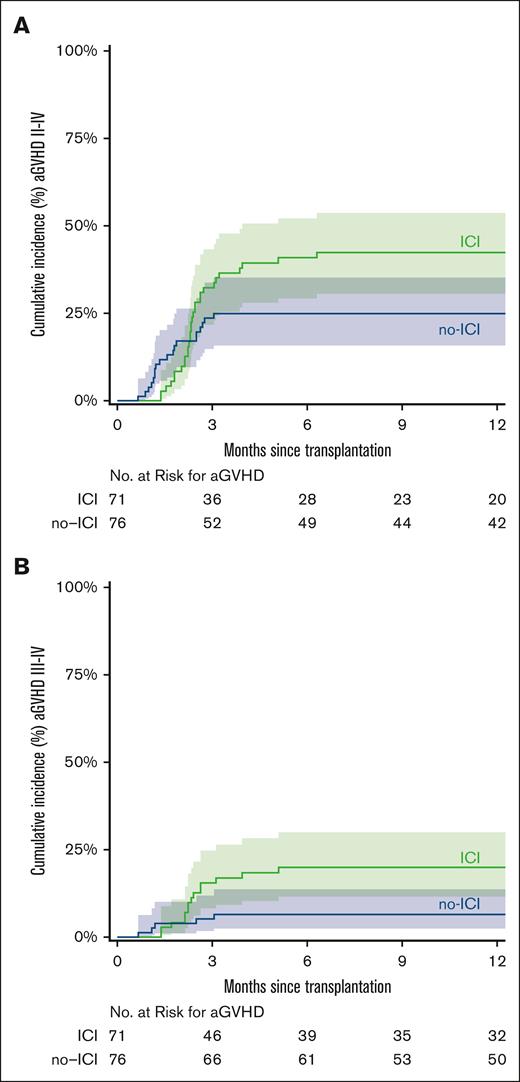

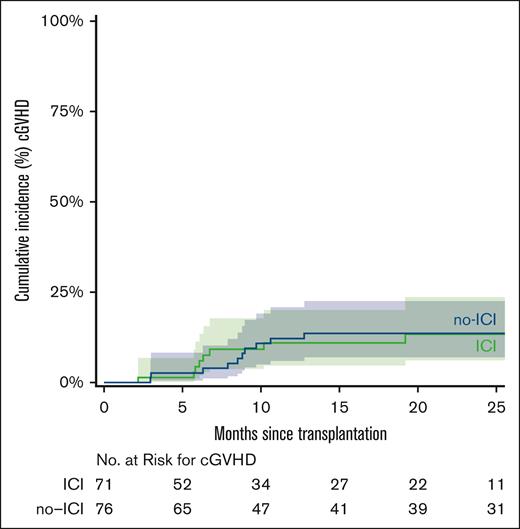

The median time to neutrophil recovery was 17 days in the ICI cohort and 16 days in the no-ICI cohort. The median time to platelet recovery was 25 days in ICI patients and 24 days in no-ICI patients (Table 2). Day 60 chimerism analysis showed that full donor chimerism (≥95% donor) was achieved in 43 (60.5%) vs 64 patients (84.2%) in the ICI and no-ICI groups, respectively (Table 2). Graft failure (<5% donor) occurred in 12 ICI patients (16.9%) and 4 no-ICI patients (5.3%; χ2 = 5; P = .03). Sixteen ICI (22.5%) vs 8 no-ICI patients (10.5 %) exhibited mixed chimerism (5%-94% donor). The 12-month CuI of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD was 42% (ICI) and 25% (no-ICI; subdistribution hazard ratio (SDHR), 1.73; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.96-3.09; P = .07) and grade 3 to 4 GVHD was 20% (ICI) and 7% (no-ICI; SDHR, 3.16; 95% CI, 1.13-8.81; P = .03; Figure 1). The 24-month CuI of cGVHD was 13% (ICI) and 14% (no-ICI; SDHR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.38-2.41; P = .92; Figure 2).

Transplant characteristics

| . | ICIs . | No-ICIs . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor type, n (%) | P < .001 | ||

| HLA haploidentical | 48 (68%) | 70 (92%) | |

| HLA matched | 7 (10%) | 2 (3%) | |

| HLA mismatched | 16 (22%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Median donor age, (IQR), y | 28 (23-38) | 41 (26-54) | P < .001 |

| Allograft source, n (%) | P = .03 | ||

| Bone marrow | 53 (75%) | 69 (91%) | |

| Peripheral blood | 17 (24%) | 6 (8%) | |

| Cord blood | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Count recovery time, median (range), d | |||

| Days to neutrophil count recovery | 17 (12-54) | 16 (7-64) | P = .21 |

| Days to platelet count recovery | 25 (11-133) | 24 (11-79) | P = .04 |

| Engraftment/chimerism at day +60 | P = .005 | ||

| Full donor chimerism (<5% patient) | 43 (60.5%) | 64 (84.2%) | |

| Mixed chimerism (5%-94% patient) | 16 (22.5%) | 8 (10.5%) | |

| Graft failure | 12 (16.9%) | 4 (5.3%) |

| . | ICIs . | No-ICIs . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor type, n (%) | P < .001 | ||

| HLA haploidentical | 48 (68%) | 70 (92%) | |

| HLA matched | 7 (10%) | 2 (3%) | |

| HLA mismatched | 16 (22%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Median donor age, (IQR), y | 28 (23-38) | 41 (26-54) | P < .001 |

| Allograft source, n (%) | P = .03 | ||

| Bone marrow | 53 (75%) | 69 (91%) | |

| Peripheral blood | 17 (24%) | 6 (8%) | |

| Cord blood | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Count recovery time, median (range), d | |||

| Days to neutrophil count recovery | 17 (12-54) | 16 (7-64) | P = .21 |

| Days to platelet count recovery | 25 (11-133) | 24 (11-79) | P = .04 |

| Engraftment/chimerism at day +60 | P = .005 | ||

| Full donor chimerism (<5% patient) | 43 (60.5%) | 64 (84.2%) | |

| Mixed chimerism (5%-94% patient) | 16 (22.5%) | 8 (10.5%) | |

| Graft failure | 12 (16.9%) | 4 (5.3%) |

IQR, interquartile range.

CuI of aGVHD. CuI of aGVHD grade 2 to 4 (A) and grade 3 to 4 (B). The curves were truncated at 12 months. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

CuI of aGVHD. CuI of aGVHD grade 2 to 4 (A) and grade 3 to 4 (B). The curves were truncated at 12 months. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

CuI of cGVHD. The curves were truncated at 24 months. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

CuI of cGVHD. The curves were truncated at 24 months. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

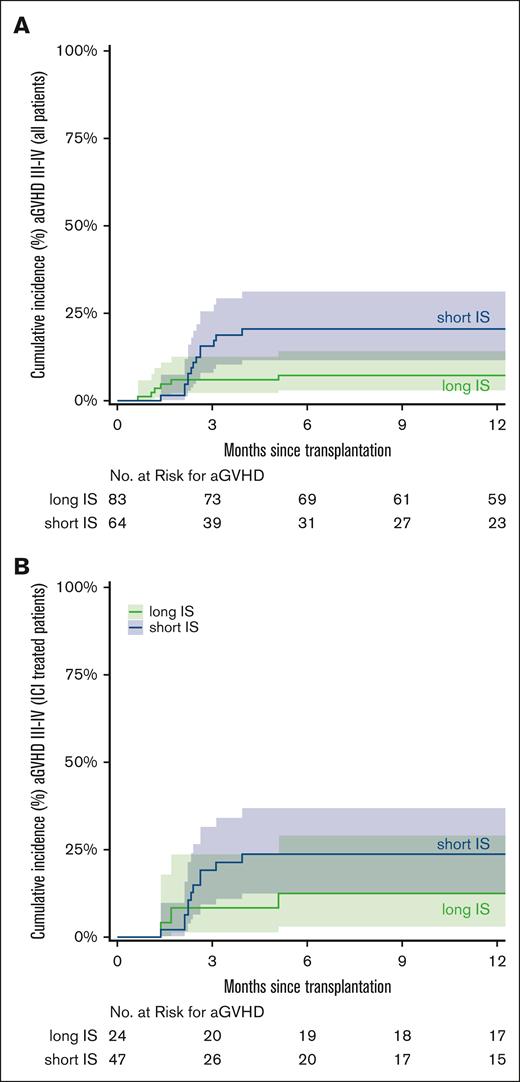

Since 2020, all patients undergoing alloBMT at Johns Hopkins received short immunosuppression (short IS) with tacrolimus till day +60, instead of long immunosuppression (long IS) with tacrolimus till day +180. This short duration of immunosuppression was based on our report that such therapy may reduce the risk of relapse while not increasing the incidence of GVHD.13 However, the report did not include patients with cHL who received ICI before alloBMT. Thus, we investigated whether the increased incidence of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD observed in the ICI cohort was driven by the short duration of immunosuppression. The CuI of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD was 21% in patients with short IS and 7% in patients with long IS (hazard ratio [HR], 2.92; 95% CI, 1.1-7.7; P = .03; Figure 3A). In the ICI cohort (n = 71 patients), we observed a CuI of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD in 11 of 47 patients (24%) with short IS and 3 of 24 patients (12%) with long IS (SDHR, 1.98; 95% CI, 0.55-7.07; P = .29; Figure 3B). CuI of aGVHD (grade 2-4) in all patients stratified by ICI exposure (ICI vs no-ICI) and duration of immunosuppression (short vs long) is shown in supplemental Figure 1.

CuI of aGVHD stratified by short vs long immunosuppression (IS). CuI of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD in short vs long IS in all 147 patients (A) and the 71 patients who received ICI (B). The curves were truncated at 12 months. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

CuI of aGVHD stratified by short vs long immunosuppression (IS). CuI of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD in short vs long IS in all 147 patients (A) and the 71 patients who received ICI (B). The curves were truncated at 12 months. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

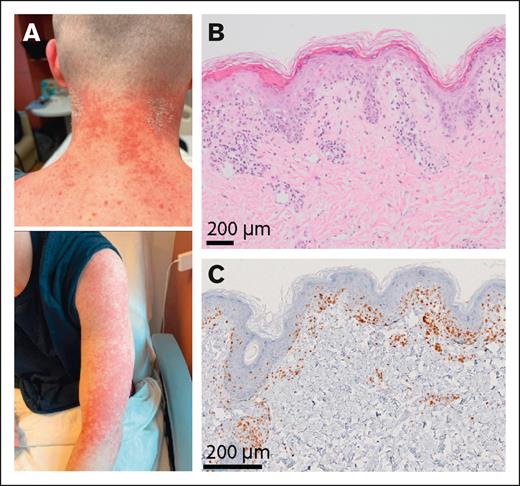

Of note, among the 14 ICI-treated patients with grade 3 to 4 aGVHD, 1 patient had graft failure, and 3 patients were mixed chimeras (Figure 4A-B). Among the 14 ICI-treated patients with grade 3 to 4 aGVHD, 4 received corticosteroids, whereas 7 required the addition of ruxolitinib. Three patients were refractory to all agents and required vedolizumab. Twelve of the 14 patients responded to therapy, and 2 patients died from aGVHD.

aGVHD in an ICI-treated patient with mixed chimera. (A) Photographs of an ICI-treated patient with mixed chimera after alloBMT who developed erythematous maculopapular skin lesions. (B) Skin sampling revealed lymphocytic exocytosis and scattered intraepidermal dyskeratotic cells, overlying a scant dermal perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes with vacuolar interface dermatitis including vacuolar changes of basal keratinocytes. (C) Immunohistochemistry using an anti-CD3 antibody showed T-cell infiltrate involving the epidermis and superficial dermis.

aGVHD in an ICI-treated patient with mixed chimera. (A) Photographs of an ICI-treated patient with mixed chimera after alloBMT who developed erythematous maculopapular skin lesions. (B) Skin sampling revealed lymphocytic exocytosis and scattered intraepidermal dyskeratotic cells, overlying a scant dermal perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes with vacuolar interface dermatitis including vacuolar changes of basal keratinocytes. (C) Immunohistochemistry using an anti-CD3 antibody showed T-cell infiltrate involving the epidermis and superficial dermis.

Relapse and NRM

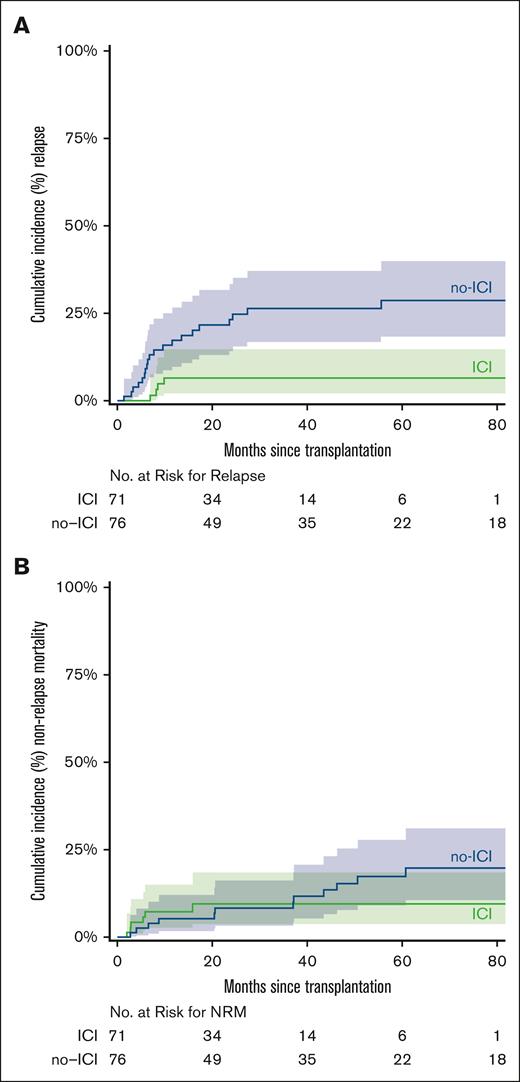

The CuI of relapse at 3 years was 7% (95% CI, 0-13) in ICI vs 26% (95% CI, 16-37) in no-ICI (SDHR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.08-0.68; P = .01; Figure 5A). The NRM at 5 years was 9% in ICI (95% CI, 2-17) vs 17% in no-ICI (95% CI, 8-27; SDHR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.32-2.03; P = .65; Figure 5B). The CuI of relapse in patients who progressed after autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) and received salvage ICI followed by alloBMT (n = 12 patients) was 17% vs 27% in those with salvage chemotherapy followed by alloBMT (n = 27 patients) at 3 years (SDHR, 0.56; P = .43). Long IS did not increase the risk of relapse compared with short IS. The CuI of relapse at 3 years was 21% for long IS vs 15% for short IS (SDHR, 0.63; P = .3; supplemental Figure 2).

CuI of relpase and NRM stratified by ICI vs no-ICI. CuI of relapse (A) and NRM (B) after alloBMT with PTCy. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

CuI of relpase and NRM stratified by ICI vs no-ICI. CuI of relapse (A) and NRM (B) after alloBMT with PTCy. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

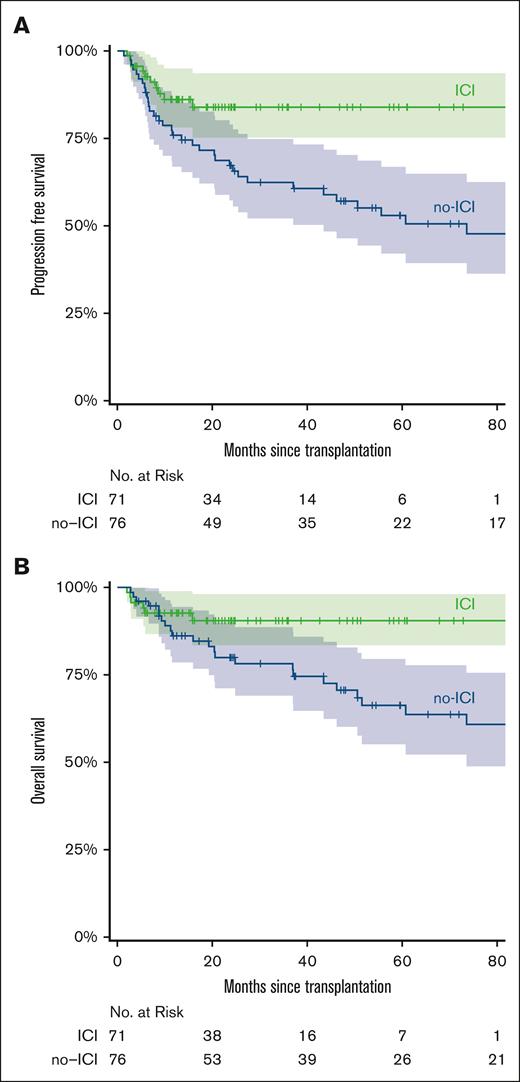

Survival

The median patient follow-up was 22.7 months (range, 2.6-86.6) and 65.4 months (range, 4.5-206.9) for the ICI and no-ICI cohorts, respectively. The 5-year estimated PFS for the ICI and no-ICI cohorts was 84% and 53%, respectively (HR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.2-0.81; P = .011; Figure 6A). The 5-year estimated OS was 91% (ICI) vs 66% (no-ICI; HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.16-0.98; P = .046; Figure 6B). The 12 ICI patients with graft failures continued to be in CR, did not require additional treatment, and were disease free at the last follow-up (median, 19 months [range, 4.1-70.8]). Fourteen of the 16 ICI-treated patients with mixed chimerism were disease free at the last follow-up. Patients received ICI from 2015 onward. To account for time bias, we performed a subgroup analysis of patients undergoing alloBMT between 2015 and 2023. Within this subgroup, we found a significant difference in PFS between the no-ICI vs ICI cohorts (median survival, 46.2 months vs not reached; HR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.17-0.89; P = .025). However, median OS was not reached in both no-ICI and ICI cohorts due to the limited number of events between 2015 and 2023 (supplemental Figure 3).

Survival stratified by ICI vs no-ICI. Kaplan-Meier curve for PFS (A) and OS (B) in ICI or no-ICI pretreated alloBMT patients. The curves are truncated at 80 months. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

Survival stratified by ICI vs no-ICI. Kaplan-Meier curve for PFS (A) and OS (B) in ICI or no-ICI pretreated alloBMT patients. The curves are truncated at 80 months. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI.

Discussion

ICIs enhance T-cell killing by blocking the pathways that downregulate T cells.14 Currently, ICIs are approved for the treatment of adult patients with R/R cHL and pediatric patients who have relapsed after ≥2 lines of therapy.15 A recent phase 3 clinical trial (SWOG S1826) demonstrated that first-line ICI in combination with chemotherapy in cHL improves PFS compared with brentuximab with chemotherapy. Thus, it is expected that ICI in combination with chemotherapy may soon be the standard first-line therapy in cHL.16 As a result, the vast majority of patients with cHL who relapse after initial treatment will be exposed to ICI. Such relapsed patients with cHL often require consolidation with autologous BMT or alloBMT. Prior reports, including our own, were only able to demonstrate a PFS benefit in ICI cohorts with consolidation alloBMT.5,17 Our current report indicates that patients who received ICI experienced improved 5-year OS compared with salvage chemotherapy, despite a lower number of patients in the ICI cohort entering alloBMT in CR. The improvement in OS was driven by a reduced incidence of relapse in the ICI cohort. This is congruent with prior reports of ICIs improving survival by sensitizing patients to subsequent therapies in cHL,18,19 but the underlying mechanisms that drive this phenomenon remain unclear.

Exposure to ICIs was associated with an increased risk of graft failure. ICIs are known to increase the risk of rejection in patients with solid organ transplants.20,21 Thus, a similar mechanism of host T-cell–mediated rejection of the donor blood or marrow graft may be driving graft rejection. However, consistent with our prior report, none of the 12 patients with graft failure experienced disease relapse.5,9,22 Several reports have documented tumor regressions and durable remissions in a variety of hematologic malignancies after NMA alloBMT after unintentional rejection of (usually mismatched) donor allografts.23-25 Potential mechanisms for an antitumor effect associated with graft loss include an effect of conditioning, although the relatively low doses may make this unlikely, a transient graft-versus-host reaction by donor T or natural killer cells, or an abrogation of host tolerance to tumor by either the graft-versus-host or host-versus-graft reactions. ICI could augment any of these mechanisms.

ICI treatment was also associated with an increase in the CuI of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD compared with patients treated with salvage chemotherapy. Within the ICI cohort, we also observed a trend toward increased CuI of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD in patients who received short IS compared with patients who received long IS. Similarly, short IS was associated with a statistically significant increase in grade 3 to 4 aGVHD when evaluating all patients who underwent alloBMT. Thus, the increase in grade 3 to 4 aGVHD in ICI patients was likely due to the very high incidence of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD in the subset of patients who received short IS. Interestingly, 4 ICI-treated patients developed grade 3 to 4 aGVHD after graft failure or in the setting of mixed chimerism. Thus, these patients are likely better categorized as experiencing ICI toxicity rather than true GVHD. Steroid and ruxolitinib refractory aGVHD requiring therapy with vedolizumab is associated with a high risk of GVHD-related mortality.26 However, in our cohort, the majority of patients responded to a combination of agents including ruxolitinib and vedolizumab.

Most patients treated with ICI experience excellent outcomes after ASCT.3 However, survival is less favorable for patients with poor response to ICI and patients with residual PET-positive disease before ASCT.3 In patients who progressed after ASCT, we noticed a trend toward lower relapse in patients treated with ICI vs no-ICI followed by alloBMT (17% vs 27%; P = .43). Thus, alloBMT remains a viable option for such patients who progress after ASCT or have a poor response to salvage ICI with residual positron emission tomography PET-positive disease. Limitations of the study include its retrospective nature and time bias because the ICI cohort received treatment after 2015 and may have benefited from advancements in supportive care. Our post-2015 analysis also demonstrated improved PFS in the ICI cohort, which suggests that the survival difference was not likely due to time bias. Overall, our findings suggest that ICI before alloBMT with PTCy GVHD prophylaxis in cHL is a safe and effective treatment option that reduces disease relapse and improves OS. To reduce the risk of aGVHD, we now use long IS (till day +180) in patients with cHL who received ICI before alloBMT.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the exceptional clinical care provided by nurses, physicians, and staff at the bone marrow transplant coordinator’s office and the cell therapy laboratory. The visual abstract was generated by BioRender.com.

S.P. was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI; grant K08CA270403), the Leukemia Lymphoma Society Translation Research Program award (grant 6666-23), the American Society of Hematology Scholar award, and the Swim Across America Translational Cancer Research award. R.V, M.Z, and this study were supported by the National Institutes of Health, NCI (grants PO1 CA225618 and P30 CA06973).

Authorship

Contribution: N.T., M.Z., R.V., and S.P. conceptualized the study; N.T. and I.M.T. collected data; M.Z. and R.V. performed statistical analysis; R.V. and S.P. supervised the study; C.H.S., J.B.-M., L.J.S., N.W.-J., R.F.A., E.J.F., and R.J.J. contributed patients and analyzed data; N.T., M.Z., R.V., and S.P. wrote the manuscript; and all the authors participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.P. is a consultant to Merck; owns equity in Gilead; and received payment from IQVIA and Curio Science. J.B.-M. has received honoraria from Incyte Corporation as a member of their data monitoring committee. C.H.S. has received honoraria from Medical Logix and Haymarket Medical Education; and participates in advisory boards or provides consulting for Kyowa Kirin and Acrotech Biopharma. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Suman Paul, Department of Oncology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, CRB1, Rm 3M90, 1650 Orleans St, Baltimore, MD 21287; email: spaul19@jhmi.edu; and Ravi Varadhan, Department of Oncology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Rm 1103-C, 550 N Broadway, Baltimore MD 21287; email: ravi.varadhan@jhmi.edu.

References

Author notes

N.T. and M.Z. contributed equally to this study.

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Suman Paul (spaul19@jhmi.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.