Visual Abstract

Over the past decade, treatment recommendations for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) have shifted from traditional chemoimmunotherapy to targeted therapies. Multiple new therapies are commercially available, and, in many cases, a lack of randomized clinical trial data makes selection of the optimal treatment for each patient challenging. Additionally, many patients continue to receive chemoimmunotherapy in the United States, suggesting a gap between guidelines and real-world practice. The Lymphoma Research Foundation convened a workshop comprising a panel of CLL/SLL experts in the United States to develop consensus recommendations for selection and sequencing of therapies for patients with CLL/SLL in the United States. Herein, the recommendations are compiled for use as a practical clinical guide for treating providers caring for patients with CLL/SLL, which complement existing guidelines by providing a nuanced discussion relating how our panel of CLL/SLL experts in the United States care for patients in a real-world environment.

Introduction

Therapeutic advances in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) have led to a paradigm shift from chemoimmunotherapy to targeted therapies and improved patient outcomes. However, treatment selection is increasingly complex, and many patients in the United States (US) continue to receive chemoimmunotherapy, suggesting a gap between guidelines and real-world practice.1,2 Therefore, the Lymphoma Research Foundation (LRF) convened a working group to develop practical recommendations for treatment selection and therapeutic sequencing for patients with CLL/SLL, focusing on US providers and patients.

Methodology

An adapted Delphi method was used to develop consensus. The working group reviewed the objectives, providing initial feedback to J.D.S. and D.M.S. who developed the program. Workshops were moderated by J.D.S./D.M.S. (10 January 2024, 29 January 2024, and 25 March 2024). The working group members were selected to ensure broad representation by geography and institutions, and LRF scholar award recipients with a career interest in CLL/SLL were included. Relevant literature was reviewed, and the panel completed ad hoc anonymous questionnaires before/after each conference, which served as the basis for consensus. Areas of disagreement/alignment were discussed until consensus was reached (unanimous agreement attempted; ≤1 dissent permitted). J.D.S./D.M.S. wrote the manuscript, which panel members edited to ensure it reflected consensus. Equivalent options were listed alphabetically. Nonbinding/noniterative feedback was solicited from industry (supplemental table 9). Although for some therapies’ high copayments can be prohibitive, copayment assistance programs are available through foundations, and free drug programs are available through pharmaceutical companies, thus the panel provided a reference to the LRF Patient Assistance Program but did not consider cost/access in consensus development. English and Spanish patient materials incorporated feedback from individuals without medical training. The LRF and cochairs (J.D.S./D.M.S.) will meet annually and on an ad hoc basis after major advances in CLL/SLL to determine whether to convene a LRF workshop to update consensus recommendations.

Consensus recommendations

Decision to initiate therapy

Our approach adheres to International Workshop (iwCLL) on CLL guidelines 2018 for initiation of therapy for CLL/SLL.

iwCLL criteria for therapy initiation are summarized in supplemental Table 1.3 Several randomized trials have evaluated early treatment in asymptomatic patients with CLL/SLL, uniformly demonstrating that early treatment increases toxicity without improving overall survival (OS; supplemental Table 2).4-7 Although most evaluated early traditional chemotherapy, this also includes the CLL12 trial comparing ibrutinib vs placebo, which demonstrated no OS difference.7,8 We await results from the S1925 trial, which is evaluating early fixed-duration venetoclax-obinutuzumab (Ven-O) in asymptomatic patients with high-/very high-risk CLL/SLL using the CLL International Prognostic Index compared with initiation of Ven-O at the time of meeting traditional iwCLL criteria, in which the primary end point is OS (Table 1).21

Pretreatment patient and disease assessments in CLL or SLL

| Assessment . | Description and role in prognosis and treatment selection . |

|---|---|

| Patient preference | |

| Shared decision-making discussion | As there are frequently multiple reasonable treatment options for patients with CLL/SLL, patients should be engaged in treatment discussions at all lines of therapy. This is especially crucial in the frontline setting, when deciding between a cBTKi and Ven-O (Section 4.2; Figure 1A) and in the third-line setting for patients with prior Ven and a cBTKi, when deciding between pirtobrutinib and liso-cel (Section 6.1). |

| Performance status and physical examination | |

| ECOG performance status | We assess performance status before each line of therapy (supplemental Table 12). |

| Physical examination | We evaluate for distribution and size of lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, in addition to a complete physical examination (eg, skin, head/neck, heart, lungs, and abdomen). |

| Feasibility | |

| Transportation to medical center | Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb: frequent visits are required during the ramp-up. |

| Resources at treating facility | Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb: facility must have ability to perform STAT laboratory testing and interventions if needed based on results during the ramp-up. Liso-cel: facility must be accredited for CAR T-cell therapy administration. |

| Financial implications | High copayments for oral therapies: high copayments can be prohibitive for some patients, although copayment assistance programs are available through foundations and free drug programs are available through pharmaceutical companies to address this. Refer to LRF patient assistance. Liso-cel: patient must have companion and remain within 2 h of the facility for 1 mo from cell infusion, which may require temporary leave from work for patient and companion. |

| Comorbidities | |

| AF | We evaluate for past medical history, active comorbidities, and concomitant medications that can influence treatment selection between a second-generation cBTKi vs Ven-O for previously untreated patients with CLL/SLL (Table 3; Figure 1). Additional workup w/wo referral to relevant consultants, for example, cardio-oncology, may be helpful based on initial evaluation. |

| Heart failure | |

| Hypertension | |

| Major bleeding | |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | |

| Concomitant medications | |

| Anticoagulation | Careful review of medications is necessary before each therapy, as concomitant administration of warfarin, a nonwarfarin anticoagulant, single or dual antiplatelet therapy, may influence treatment selection or require modification (Section 4.3; Figure 1). Additionally, we recommend screening patient medications for potential interactions with the therapies under consideration. When interactions exist, we work with prescribing providers to determine whether there are acceptable alternatives, and with oncology pharmacy colleagues to determine impact on dosing. |

| Warfarin | |

| LMWH, DOACs | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | |

| Single antiplatelet therapy | |

| Drug interactions | |

| Organ function | |

| Kidney and liver function | We obtain a comprehensive metabolic panel to assess for kidney and liver dysfunction and follow the treatment package inserts for dosing.9-12 Kidney dysfunction can also increase TLS risk. |

| Disease burden | |

| Hematologic function | In patients with significant neutropenia, anemia, or thrombocytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy with aspirate is useful to determine the direct cause, such as CLL/SLL-related causes (eg, marrow infiltration, splenic sequestration, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, or immune thrombocytopenia) vs other causes (eg, myelosuppression or myelodysplasia from prior treatment, or alternative causes). |

| CT imaging | Baseline CT scan may be useful at diagnosis for patients with palpable lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly, or if warranted clinically based on symptoms. Pretreatment CT imaging should be obtained in patients considering treatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb to assess TLS risk. CT imaging is usually not required for diagnosis, serial monitoring, surveillance, routine monitoring of treatment response, or progression. |

| TLS risk | Greater disease burden measured by CT imaging (eg, LN ≥ 10 cm or LN ≥ 5 cm with ALC ≥ 25 000/μL as defined in the Ven package insert), and presence of significant kidney dysfunction, may increase TLS risk. We follow treatment package inserts for TLS monitoring and preventive measures. |

| Related conditions | |

| Autoimmune complications | Presence of clinically significant autoimmune complications can influence treatment selection toward a therapy that includes an anti-CD20 mAb (Section 3). |

| Molecular testing | |

| IGHV mutation status | Diagnosis: we assess IGHV mutation status at diagnosis given association with time to initial therapy. Because IGHV mutation status is a fixed risk factor, this is assessed once, and not repeated with subsequent therapies. |

| Testing for mutations in TP53 | Diagnosis: although we often perform TP53 mutation testing at diagnosis, we acknowledge a TP53 mutation would not affect management for a patient who does not meet iwCLL 2018 criteria to initiate therapy. Prior to each line of therapy: we perform TP53 mutation testing before each line of therapy, as presence of a TP53 mutation can influence treatment selection (Section 4.4; Figure 1C). Some panels include additional genes ATM, NOTCH1, SF3B1, and RAS/RAF mutations, which provide additional biological information about a patient’s disease, but these do not affect patient management. Previously treated with a BTKi: for patients who were previously treated with a BTKi, detecting mutations in BTK and/or PLCG2 associated with resistance to BTKis may provide biological information about a patient’s disease and potential emerging resistance, but patients may continue to respond to BTKis despite the detection of these mutations (Section 11). |

| FISH for 17p del, 11q del, +12, and 13q del, and for t(11;14), if applicable | Diagnosis: although we often obtain FISH to assess for 17p deletion, 11q deletion, 13q deletion, and trisomy 12, before each line of therapy, we acknowledge a 17p deletion would not affect management for a patient who does not meet iwCLL 2018 criteria to initiate therapy. Before each line of therapy: we obtain FISH to assess for 17p deletion, 11q deletion, 13q deletion, and trisomy 12, before each line of therapy, as presence of 17p deletion can influence treatment selection (Section 4.4; Figure 1C). Although an 11q deletion carried a negative prognosis with traditional chemoimmunotherapy, this does not appear so with modern therapies.13 Note regarding t(11;14): FISH for t(11;14) may be necessary to evaluate for mantle cell lymphoma, if CLL is otherwise diagnosed in peripheral blood only. FISH for t(11;14) is typically sufficient to rule out mantle cell lymphoma, although in some cases (eg, when circulating disease immunophenotype is otherwise typical of mantle cell lymphoma [eg, CD200− and CD23−] histologic confirmation may be necessary). |

| CpG-stimulated karyotype | Diagnosis: we obtain CpG-stimulated metaphase karyotype or SNP array to assess for karyotypic complexity at diagnosis. However, these results would not affect management for a patient who does not meet iwCLL 2018 criteria to initiate therapy. Before each line of therapy: we obtain CpG-stimulated metaphase karyotype or SNP array to assess for karyotypic complexity, as this is relevant to understanding prognosis. However, this does not currently affect treatment selection (Section 4.4). |

| Prognostic systems | |

| CLL-IPI score | The CLL-IPI is a validated prognostic model for patients with CLL/SLL receiving frontline therapy, for whom it predicts PFS (targeted therapies or traditional chemotherapy) w/wo OS (traditional chemotherapy), as well as for treatment-naïve patients on active surveillance, for whom it predicts time to initial therapy.14-16 The risk score is available on Calculate by QxMD. |

| BALL risk score | The BALL score was derived in patients with R/R CLL/SLL receiving cBTKis, and has been validated for patients with R/R CLL/SLL on a cBTKi, PI3Kδ, or Ven-based therapy, for whom it is prognostic for OS.17,18 Additionally, a low-risk BALL score (0-1) is associated with a higher likelihood of achieving response to liso-cel.19 The risk score is available on Calculate by QxMD. |

| 4-Factor model | The 4-factor model was derived and validated in patients with CLL/SLL receiving ibrutinib, for whom it is prognostic for PFS, OS, and cumulative incidence of BTK and PLCG2 mutations.20 |

| Suspicion for Richter transformation | |

| Assess for clinical suspicion of Richter transformation to DLBCL or HL. | Richter transformation should be considered in patients with B-symptoms, rapid progression, asymmetric progression, or significantly elevated lactate dehydrogenase without an alternative cause (eg, presence of hemolysis). |

| FDG-PET/CT imaging to direct biopsy | FDG-PET imaging should be obtained if Richter transformation is suspected. Because CLL/SLL is typically not hypermetabolic on FDG-PET imaging, we use FDG-PET/CT imaging to identify more FDG-avid sites of disease for biopsy to exclude Richter transformation (excisional biopsy preferred when feasible). |

| Assessment . | Description and role in prognosis and treatment selection . |

|---|---|

| Patient preference | |

| Shared decision-making discussion | As there are frequently multiple reasonable treatment options for patients with CLL/SLL, patients should be engaged in treatment discussions at all lines of therapy. This is especially crucial in the frontline setting, when deciding between a cBTKi and Ven-O (Section 4.2; Figure 1A) and in the third-line setting for patients with prior Ven and a cBTKi, when deciding between pirtobrutinib and liso-cel (Section 6.1). |

| Performance status and physical examination | |

| ECOG performance status | We assess performance status before each line of therapy (supplemental Table 12). |

| Physical examination | We evaluate for distribution and size of lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, in addition to a complete physical examination (eg, skin, head/neck, heart, lungs, and abdomen). |

| Feasibility | |

| Transportation to medical center | Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb: frequent visits are required during the ramp-up. |

| Resources at treating facility | Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb: facility must have ability to perform STAT laboratory testing and interventions if needed based on results during the ramp-up. Liso-cel: facility must be accredited for CAR T-cell therapy administration. |

| Financial implications | High copayments for oral therapies: high copayments can be prohibitive for some patients, although copayment assistance programs are available through foundations and free drug programs are available through pharmaceutical companies to address this. Refer to LRF patient assistance. Liso-cel: patient must have companion and remain within 2 h of the facility for 1 mo from cell infusion, which may require temporary leave from work for patient and companion. |

| Comorbidities | |

| AF | We evaluate for past medical history, active comorbidities, and concomitant medications that can influence treatment selection between a second-generation cBTKi vs Ven-O for previously untreated patients with CLL/SLL (Table 3; Figure 1). Additional workup w/wo referral to relevant consultants, for example, cardio-oncology, may be helpful based on initial evaluation. |

| Heart failure | |

| Hypertension | |

| Major bleeding | |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | |

| Concomitant medications | |

| Anticoagulation | Careful review of medications is necessary before each therapy, as concomitant administration of warfarin, a nonwarfarin anticoagulant, single or dual antiplatelet therapy, may influence treatment selection or require modification (Section 4.3; Figure 1). Additionally, we recommend screening patient medications for potential interactions with the therapies under consideration. When interactions exist, we work with prescribing providers to determine whether there are acceptable alternatives, and with oncology pharmacy colleagues to determine impact on dosing. |

| Warfarin | |

| LMWH, DOACs | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | |

| Single antiplatelet therapy | |

| Drug interactions | |

| Organ function | |

| Kidney and liver function | We obtain a comprehensive metabolic panel to assess for kidney and liver dysfunction and follow the treatment package inserts for dosing.9-12 Kidney dysfunction can also increase TLS risk. |

| Disease burden | |

| Hematologic function | In patients with significant neutropenia, anemia, or thrombocytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy with aspirate is useful to determine the direct cause, such as CLL/SLL-related causes (eg, marrow infiltration, splenic sequestration, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, or immune thrombocytopenia) vs other causes (eg, myelosuppression or myelodysplasia from prior treatment, or alternative causes). |

| CT imaging | Baseline CT scan may be useful at diagnosis for patients with palpable lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly, or if warranted clinically based on symptoms. Pretreatment CT imaging should be obtained in patients considering treatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb to assess TLS risk. CT imaging is usually not required for diagnosis, serial monitoring, surveillance, routine monitoring of treatment response, or progression. |

| TLS risk | Greater disease burden measured by CT imaging (eg, LN ≥ 10 cm or LN ≥ 5 cm with ALC ≥ 25 000/μL as defined in the Ven package insert), and presence of significant kidney dysfunction, may increase TLS risk. We follow treatment package inserts for TLS monitoring and preventive measures. |

| Related conditions | |

| Autoimmune complications | Presence of clinically significant autoimmune complications can influence treatment selection toward a therapy that includes an anti-CD20 mAb (Section 3). |

| Molecular testing | |

| IGHV mutation status | Diagnosis: we assess IGHV mutation status at diagnosis given association with time to initial therapy. Because IGHV mutation status is a fixed risk factor, this is assessed once, and not repeated with subsequent therapies. |

| Testing for mutations in TP53 | Diagnosis: although we often perform TP53 mutation testing at diagnosis, we acknowledge a TP53 mutation would not affect management for a patient who does not meet iwCLL 2018 criteria to initiate therapy. Prior to each line of therapy: we perform TP53 mutation testing before each line of therapy, as presence of a TP53 mutation can influence treatment selection (Section 4.4; Figure 1C). Some panels include additional genes ATM, NOTCH1, SF3B1, and RAS/RAF mutations, which provide additional biological information about a patient’s disease, but these do not affect patient management. Previously treated with a BTKi: for patients who were previously treated with a BTKi, detecting mutations in BTK and/or PLCG2 associated with resistance to BTKis may provide biological information about a patient’s disease and potential emerging resistance, but patients may continue to respond to BTKis despite the detection of these mutations (Section 11). |

| FISH for 17p del, 11q del, +12, and 13q del, and for t(11;14), if applicable | Diagnosis: although we often obtain FISH to assess for 17p deletion, 11q deletion, 13q deletion, and trisomy 12, before each line of therapy, we acknowledge a 17p deletion would not affect management for a patient who does not meet iwCLL 2018 criteria to initiate therapy. Before each line of therapy: we obtain FISH to assess for 17p deletion, 11q deletion, 13q deletion, and trisomy 12, before each line of therapy, as presence of 17p deletion can influence treatment selection (Section 4.4; Figure 1C). Although an 11q deletion carried a negative prognosis with traditional chemoimmunotherapy, this does not appear so with modern therapies.13 Note regarding t(11;14): FISH for t(11;14) may be necessary to evaluate for mantle cell lymphoma, if CLL is otherwise diagnosed in peripheral blood only. FISH for t(11;14) is typically sufficient to rule out mantle cell lymphoma, although in some cases (eg, when circulating disease immunophenotype is otherwise typical of mantle cell lymphoma [eg, CD200− and CD23−] histologic confirmation may be necessary). |

| CpG-stimulated karyotype | Diagnosis: we obtain CpG-stimulated metaphase karyotype or SNP array to assess for karyotypic complexity at diagnosis. However, these results would not affect management for a patient who does not meet iwCLL 2018 criteria to initiate therapy. Before each line of therapy: we obtain CpG-stimulated metaphase karyotype or SNP array to assess for karyotypic complexity, as this is relevant to understanding prognosis. However, this does not currently affect treatment selection (Section 4.4). |

| Prognostic systems | |

| CLL-IPI score | The CLL-IPI is a validated prognostic model for patients with CLL/SLL receiving frontline therapy, for whom it predicts PFS (targeted therapies or traditional chemotherapy) w/wo OS (traditional chemotherapy), as well as for treatment-naïve patients on active surveillance, for whom it predicts time to initial therapy.14-16 The risk score is available on Calculate by QxMD. |

| BALL risk score | The BALL score was derived in patients with R/R CLL/SLL receiving cBTKis, and has been validated for patients with R/R CLL/SLL on a cBTKi, PI3Kδ, or Ven-based therapy, for whom it is prognostic for OS.17,18 Additionally, a low-risk BALL score (0-1) is associated with a higher likelihood of achieving response to liso-cel.19 The risk score is available on Calculate by QxMD. |

| 4-Factor model | The 4-factor model was derived and validated in patients with CLL/SLL receiving ibrutinib, for whom it is prognostic for PFS, OS, and cumulative incidence of BTK and PLCG2 mutations.20 |

| Suspicion for Richter transformation | |

| Assess for clinical suspicion of Richter transformation to DLBCL or HL. | Richter transformation should be considered in patients with B-symptoms, rapid progression, asymmetric progression, or significantly elevated lactate dehydrogenase without an alternative cause (eg, presence of hemolysis). |

| FDG-PET/CT imaging to direct biopsy | FDG-PET imaging should be obtained if Richter transformation is suspected. Because CLL/SLL is typically not hypermetabolic on FDG-PET imaging, we use FDG-PET/CT imaging to identify more FDG-avid sites of disease for biopsy to exclude Richter transformation (excisional biopsy preferred when feasible). |

ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; BALL, β2-microglobulin (≥5mg/dL), Anemia (HGB <12 g/dL for men or <11 g/dL for women), LDH (above upper limit of normal), and Last therapy (time from initiation of last therapy ≥24 months); CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CLL-IPI; CLL-International Prognostic Index; CpG, cytidine monophosphate guanosine oligodeoxynucleotide; CT, computed tomography; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FDG-PET, fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; LMHW, low molecular weight heparin; LN, lymph node; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; STAT, statim (Latin for “immediate”); TLS, tumor lysis syndrome.

Recommended frontline therapeutic options

This section describes the frontline therapies we recommend for patients with CLL/SLL.

When initial treatment of CLL/SLL is advised, we advise against the use of traditional chemotherapy agents such as fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, bendamustine, and chlorambucil

We advise against traditional chemoimmunotherapy in CLL/SLL because randomized phase 3 trials have consistently demonstrated that use of targeted therapy (1) prolongs progression-free survival (PFS), and, in some cases, OS; and (2) demonstrates a favorable safety profile compared with chemoimmunotherapy (supplemental Table 4).22-38

Historically, we considered fludarabine, cyclophosphamide plus rituximab (FCR) for young, fit patients with low-risk CLL/SLL (immunoglobulin heavy chain [IGHV] mutated; absence of del(17p)/del(11q)), for whom there is potential for functional cure (54% progression free without recurrences at >12 years).39 However, we do not recommend FCR given the availability of alternative effective treatment options, as well as prolonged immunosuppression and secondary cancers associated with FCR, with secondary myelodysplasia/acute myeloid leukemia occurring in ∼5% of patients.

When initial treatment of CLL/SLL is advised, we recommend targeted agents such as Ven-O, acalabrutinib w/wo obinutuzumab, or zanubrutinib

Prospective data directly comparing Ven-O, acalabrutinib with/without (w/wo) obinutuzumab, and zanubrutinib for the frontline treatment of CLL/SLL are unavailable to determine a single, standard initial treatment in CLL/SLL. Section 4 describes how to develop an individualized treatment plan. Supplemental Table 3 summarizes dose/administration recommendations.

Differences in treatment duration limit direct comparisons of these regimens, with covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (cBTKis) administered continuously until progression/intolerance, and Ven-O administered over 12 months.9-11,32-38 We await results from the CLL17 trial, which randomizes patients with CLL/SLL requiring frontline therapy to receive ibrutinib (continuous), Ven-O (12 months), or Ven-ibrutinib (15 months), which may start to address this knowledge gap.40

Fixed-duration therapy with ibrutinib and Ven (I-Ven) is available in Europe and the United Kingdom based on the GLOW trial.41 I-Ven has not been approved in the United States and was not included as a preferred frontline therapy by our panel. As of the date of this publication, results from the AMPLIFY phase 3 trial of acalabrutinib and Ven w/wo obinutuzumab vs chemoimmunotherapy in treatment-naïve CLL/SLL are expected soon. As a result, acalabrutinib and Ven might emerge as an attractive option for patients who favor time-limited therapy and prefer oral therapy alone, and whose past medical history, active comorbidities, and concomitant medications make them good candidates for cBTKi-based therapy (see Section 4).

Choice of cBTKi in CLL/SLL

When a cBTKi is used in CLL/SLL, we recommend use of a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) over ibrutinib. We refrain from singling out acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib as the preferred second-generation cBTKi. This choice can be individualized based on review of patient comorbidities and the safety profiles of acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib.

We recommend use of a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) over ibrutinib based on the ELEVATE-RR and ALPINE trials in patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) CLL/SLL.42,43 Acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib were at least as effective, and better tolerated, compared with ibrutinib (supplemental Table 5). These data have been extrapolated to the frontline setting in which direct head-to-head comparisons are unavailable. Ibrutinib dose optimization studies to improve safety are ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05963074). Without randomized data demonstrating comparable safety and efficacy, these data would not affect our recommendation to use a second-generation cBTKi.

Acalabrutinib vs ibrutinib

In ELEVATE-RR, 533 patients with R/R CLL with del(17p) or del (11q) were randomized to receive acalabrutinib at 100 mg orally twice daily or ibrutinib at 420 mg orally daily, continuously until progression or intolerance.42,44 ELEVATE-RR met its primary end point, demonstrating that the PFS for acalabrutinib was noninferior to ibrutinib, with both arms achieving a median PFS of 38.4 months. Rates of atrial fibrillation/flutter (AF) and hypertension were lower with acalabrutinib, whereas rate of headache was higher.

Zanubrutinib vs ibrutinib

In ALPINE, 652 patients with R/R CLL (all risk) were randomized to receive zanubrutinib at 160 mg orally twice a day vs ibrutinib at 420 mg orally once a day until progression or intolerance.43 ALPINE was designed to determine superiority of zanubrutinib for overall response rate (ORR; primary end point). PFS was a secondary end point. ALPINE met its primary end point, with zanubrutinib resulting in higher ORR (85% vs 74%) and improved PFS (3-year PFS, 65% vs 55%). Rates of AF were lower with zanubrutinib, whereas rates of hypertension were similar.

Acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib

In the absence of randomized data directly comparing acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, despite differences in PFS outcomes between the ALPINE and ELEVATE-RR trials, our panel cannot single out either as the preferred agent. Differences between the ALPINE and ELEVATE-RR patient populations limit cross-trial comparisons. cBTKi selection is tailored to the individual patient and is often based on comorbidities and possible differences in safety profiles. For instance, acalabrutinib may be preferred in a patient with uncontrolled hypertension whereas zanubrutinib may be preferred in a patient with chronic/severe headaches.

Dosing of cBTKi

Acalabrutinib is administered at 100 mg orally twice daily.10 The majority of data supporting zanubrutinib in CLL/SLL used a dose of 160 mg orally twice daily, informed by phase 1 data demonstrating near-complete (>95%) nodal BTK occupancy in 89% at 160 mg twice daily vs 50% at 320 mg daily (P = .03).45 Although the zanubrutinib label was also approved with alternate dose of 320 mg orally daily, a consideration for patients with poor adherence or strong preference for daily dosing, the panel recommends administering zanubrutinib at 160 mg twice daily as in its CLL/SLL registration trials.

When to add obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib in treatment-naïve CLL/SLL

Although the addition of obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib for frontline treatment of CLL/SLL may be associated with a longer PFS compared with acalabrutinib alone, the majority of the panel does not routinely add obinutuzumab. In previously untreated patients with CLL/SLL, the addition of obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib was associated with longer PFS (6-year PFS of 78% vs 62%), making this a reasonable option.46 Despite this PFS benefit, among patients who select a cBTKi over Ven-O, many do so to avoid intravenous infusion therapy. Addition of acalabrutinib is also associated with increased toxicity. Therefore, the panel reported that they add obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib in a minority of patients, and the most common reason provided was the presence of uncontrolled autoimmune cytopenias. Although most of the evidence for an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb) in refractory autoimmune cytopenias was with rituximab, small case series have demonstrated that obinutuzumab can be effective in this setting, which is consistent with our clinical experience.47,48

Selection of initial therapy

This section describes how to choose between a cBTKi or Ven-O for frontline treatment of CLL/SLL. See Section 3 for recommendations regarding when to add obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib.

Our specific treatment recommendations should be tailored to each individual patient

Routine pretreatment assessments and their roles in estimating prognosis and selecting therapy are shown in Table 1. We individualize recommendations for each patient after considering relevant pretreatment factors (Figure 1).

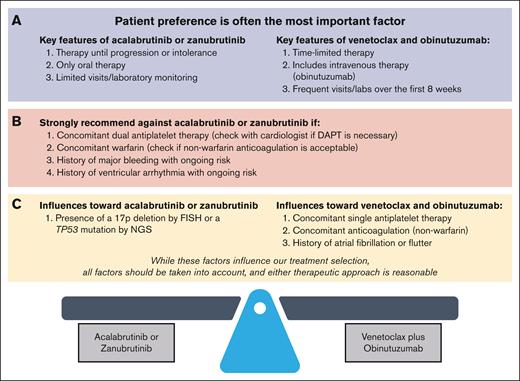

When to use a cBTKi vs Ven-O in CLL or SLL. We individualize treatment recommendations for each patient after considering relevant pretreatment factors. (A) Patient preference is a very important factor when selecting between a cBTKi and Ven-O as initial therapy. Key differences affecting patient preference include: (1) therapy until progression or intolerance vs time-limited therapy, (2) oral therapy alone vs addition of intravenous obinutuzumab, and (3) limited vs frequent visits/laboratory testing over the first 8 weeks on therapy (refer to Section 4.2). (B) For patients with concomitant warfarin or dual antiplatelet therapy, or a history of major bleeding with ongoing bleeding risk, or a history of ventricular arrhythmias with ongoing ventricular arrhythmia risk, we strongly recommend Ven-O over a cBTKi. Although concomitant use of a nonwarfarin anticoagulation or single antiplatelet therapy, or a history of AF, influences treatment selection toward Ven-O, a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) remains a reasonable option (refer to Section 4.3). (C) When considering these molecular risk factors, the most impactful for treatment selection is 17p deletion or TP53 mutation (del(17p)/TP53M), which influences treatment selection toward a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib). Given the lack of direct comparison of a cBTKi and Ven-O in this population, and taking other factors including patient preference into account, Ven-O remains a reasonable option for patients with CLL/SLL with del(17p)/TP53M (refer to Section 4.4). DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy.

When to use a cBTKi vs Ven-O in CLL or SLL. We individualize treatment recommendations for each patient after considering relevant pretreatment factors. (A) Patient preference is a very important factor when selecting between a cBTKi and Ven-O as initial therapy. Key differences affecting patient preference include: (1) therapy until progression or intolerance vs time-limited therapy, (2) oral therapy alone vs addition of intravenous obinutuzumab, and (3) limited vs frequent visits/laboratory testing over the first 8 weeks on therapy (refer to Section 4.2). (B) For patients with concomitant warfarin or dual antiplatelet therapy, or a history of major bleeding with ongoing bleeding risk, or a history of ventricular arrhythmias with ongoing ventricular arrhythmia risk, we strongly recommend Ven-O over a cBTKi. Although concomitant use of a nonwarfarin anticoagulation or single antiplatelet therapy, or a history of AF, influences treatment selection toward Ven-O, a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) remains a reasonable option (refer to Section 4.3). (C) When considering these molecular risk factors, the most impactful for treatment selection is 17p deletion or TP53 mutation (del(17p)/TP53M), which influences treatment selection toward a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib). Given the lack of direct comparison of a cBTKi and Ven-O in this population, and taking other factors including patient preference into account, Ven-O remains a reasonable option for patients with CLL/SLL with del(17p)/TP53M (refer to Section 4.4). DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy.

Patient preference is a very important factor when selecting between a second-generation cBTKi and Ven-O as initial therapy. Key differences affecting patient preference include: (1) therapy until progression or intolerance vs time-limited therapy, (2) oral therapy alone vs addition of intravenous obinutuzumab, and (3) limited vs frequent visits/laboratories over the first 8 weeks on therapy

Most patients with CLL/SLL do not have a definitive indication for a specific frontline therapy (Figure 1B), making either a second-generation cBTKi or Ven-O reasonable options. In such cases, selection of initial therapy should be driven by patient preference, informed by understanding the treatments themselves (Figure 1A) and other patient and disease-related factors (Figure 1C).

Patients who prioritize all-oral medication without intravenous therapy or wish to avoid frequent visits and laboratory testing required over the first 8 weeks of Ven-O may prefer a second-generation cBTKi. Others place greater value on fixed-duration therapy to maximize time off therapy and may prefer Ven-O. We developed an educational tool, which can be shared with patients and their advocates to assist with treatment discussions.

Despite evidence that most patients with CLL/SLL want to participate in discussions regarding treatment selection, many report not having this opportunity.49 Although other factors may supersede preference and drive treatment selection for some, we strongly encourage engaging patients in treatment selection (shared decision-making).

For patients with concomitant warfarin or dual antiplatelet therapy, a history of major bleeding with ongoing bleeding risk, or a history of ventricular arrhythmias with ongoing ventricular arrhythmia risk, we strongly recommend Ven-O over a cBTKi. Although concomitant use of a nonwarfarin anticoagulant or single antiplatelet therapy, or a history of AF, influences treatment selection toward Ven-O, a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) remains a reasonable option

We recommend assessment of past medical history, active comorbidities, and concomitant medications that may influence treatment selection between a second-generation cBTKi vs Ven-O for previously untreated CLL/SLL (Table 2; Figure 1).

Past medical history, active comorbidities and concomitant medications, and therapy selection

| Nonwarfarin anticoagulant and/or single antiplatelet therapy |

| Although bleeding risk appears lower with acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib than ibrutinib, major bleeding still occurs in 3%-5% of patients.10,11,50 Bleeding risk is increased with coadministration of a nonwarfarin anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy, which influences treatment selection toward Ven-O, but the absolute difference in major bleeding risk is low (<1%-2%) and a second-generation cBTKi remains a reasonable option.10,50 It is also important to clarify the indication for anticoagulation/antiplatelet therapy, and whether its continued use is needed. |

| Warfarin anticoagulant |

| Our recommendation against concomitant warfarin with cBTKi comes from early phase 1 trials of ibrutinib, which reported subdural hematomas in patients receiving warfarin, leading subsequent trials to exclude concomitant warfarin.51 When a cBTKi is being considered in a patient on warfarin, which we consider a contraindication, use of an alternative anticoagulant is often acceptable, and even preferable for many indications. |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy |

| Data regarding safety of concurrent dual antiplatelet therapy and cBTKi is limited, as dual antiplatelet therapy use was very rare in cBTKi trials. However, major bleeding risk may already be increased up to approximately twofold with dual antiplatelet therapy vs aspirin, without addition of a cBTKi, which leads to additional antiplatelet effect.52 Therefore, we strongly recommend Ven-O over a cBTKi in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy. |

| Bleeding history |

| A history of major bleeding who have ongoing risk, eg, because of an underlying bleeding disorder or uncontrolled bleeding source, have generally been excluded from clinical trials of cBTKis. Therefore, we strongly recommend use of Ven-O over a cBTKi in these patients.22-34,42-44 Preexisting bruising or petechiae alone does not predict major bleeding and should not influence treatment selection. |

| AF history |

| AF risk is lower with acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib than ibrutinib (2% vs 9% cumulative incidence at 12 mo).42-44,53 Patients with persistent or paroxysmal AF may be safely treated with a second-generation cBTKi, although this can occasionally precipitate recurrent AF, and use of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy for AF stroke reduction increases bleeding risk. |

| Ventricular arrhythmia history |

| Ventricular arrhythmias are very rare, 6-8 per 1000 person-years with ibrutinib, and occurring less frequently with acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib.54-56 Risk factors for cBTKi-related ventricular arrhythmias are largely unknown, and ventricular arrhythmias can occur in patients without known cardiac disease. We strongly recommend against cBTKi use in patients with a history of ventricular arrhythmias unless the underlying cause is addressed. |

| Hypertension |

| Hypertension does not influence our treatment selection toward Ven-O or a cBTKi, in part because acalabrutinib has a lower incidence of hypertension compared with ibrutinib, making it an appealing cBTKi option for patients with uncontrolled or difficult-to-manage hypertension.42,44 |

| Heart failure |

| Heart failure is not a single disease and can have heterogeneous clinical manifestations, each interacting differently with treatment risks. For example, although the presence of volume overload may complicate intravenous fluid administration for Ven-treated patients with higher risk of tumor lysis syndrome, this short-term risk may be preferred as baseline heart failure increases cardiovascular risks associated with BTKis. |

| Nonwarfarin anticoagulant and/or single antiplatelet therapy |

| Although bleeding risk appears lower with acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib than ibrutinib, major bleeding still occurs in 3%-5% of patients.10,11,50 Bleeding risk is increased with coadministration of a nonwarfarin anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy, which influences treatment selection toward Ven-O, but the absolute difference in major bleeding risk is low (<1%-2%) and a second-generation cBTKi remains a reasonable option.10,50 It is also important to clarify the indication for anticoagulation/antiplatelet therapy, and whether its continued use is needed. |

| Warfarin anticoagulant |

| Our recommendation against concomitant warfarin with cBTKi comes from early phase 1 trials of ibrutinib, which reported subdural hematomas in patients receiving warfarin, leading subsequent trials to exclude concomitant warfarin.51 When a cBTKi is being considered in a patient on warfarin, which we consider a contraindication, use of an alternative anticoagulant is often acceptable, and even preferable for many indications. |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy |

| Data regarding safety of concurrent dual antiplatelet therapy and cBTKi is limited, as dual antiplatelet therapy use was very rare in cBTKi trials. However, major bleeding risk may already be increased up to approximately twofold with dual antiplatelet therapy vs aspirin, without addition of a cBTKi, which leads to additional antiplatelet effect.52 Therefore, we strongly recommend Ven-O over a cBTKi in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy. |

| Bleeding history |

| A history of major bleeding who have ongoing risk, eg, because of an underlying bleeding disorder or uncontrolled bleeding source, have generally been excluded from clinical trials of cBTKis. Therefore, we strongly recommend use of Ven-O over a cBTKi in these patients.22-34,42-44 Preexisting bruising or petechiae alone does not predict major bleeding and should not influence treatment selection. |

| AF history |

| AF risk is lower with acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib than ibrutinib (2% vs 9% cumulative incidence at 12 mo).42-44,53 Patients with persistent or paroxysmal AF may be safely treated with a second-generation cBTKi, although this can occasionally precipitate recurrent AF, and use of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy for AF stroke reduction increases bleeding risk. |

| Ventricular arrhythmia history |

| Ventricular arrhythmias are very rare, 6-8 per 1000 person-years with ibrutinib, and occurring less frequently with acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib.54-56 Risk factors for cBTKi-related ventricular arrhythmias are largely unknown, and ventricular arrhythmias can occur in patients without known cardiac disease. We strongly recommend against cBTKi use in patients with a history of ventricular arrhythmias unless the underlying cause is addressed. |

| Hypertension |

| Hypertension does not influence our treatment selection toward Ven-O or a cBTKi, in part because acalabrutinib has a lower incidence of hypertension compared with ibrutinib, making it an appealing cBTKi option for patients with uncontrolled or difficult-to-manage hypertension.42,44 |

| Heart failure |

| Heart failure is not a single disease and can have heterogeneous clinical manifestations, each interacting differently with treatment risks. For example, although the presence of volume overload may complicate intravenous fluid administration for Ven-treated patients with higher risk of tumor lysis syndrome, this short-term risk may be preferred as baseline heart failure increases cardiovascular risks associated with BTKis. |

When considering molecular risk factors, the most impactful for treatment selection is del(17p) or TP53 mutation (TP53M), which influences treatment selection toward a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib). Given the lack of direct comparison of a cBTKi and Ven-O in this population, and taking other factors including patient preference into account, Ven-O remains a reasonable option for patients with CLL/SLL with del(17p)/TP53M

We strongly recommend assessment of cytogenetic and molecular risk factors, including molecular analysis to assess IGHV mutation status; sequencing to assess TP53 mutation status; fluorescence in situ hybridization to assess 17p deletion, 11q deletion, 13q deletion, and trisomy 12; and cytidine monophosphate guanosine oligodeoxynucleotide–stimulated metaphase karyotype or single-nucleotide polymorphism array to assess for karyotypic complexity, which are crucial for understanding each patient’s prognosis (Table 1).14,15,57-64

That del(17p)/TP53M influences treatment selection toward a second-generation cBTKi (Figure 1C) is based on prospective trials of cBTKi in del(17p) CLL/SLL, as well as subgroup analyses of other cBTKi trials, which demonstrate durable PFS (2-year PFS of ∼85%-90%; supplemental Table 6).30,46,65-68 Durability of response to time-limited therapy with Ven-O in this population is less well established. In CLL14, only 25 patients with a del(17p) or TP53M received Ven-O.37 Nevertheless, the median PFS in this subgroup was 52 months, which is encouraging but less than seen with cBTKi, albeit with potential to extend benefit with retreatment. Therefore, Ven-O remains a reasonable option for patients with CLL/SLL and del(17p)/TP53M.

We acknowledge that direct comparisons of a cBTKi and Ven-O are not available in any molecular risk group (for example, del(17p)/TP53M, unmutated IGHV, or increased karyotypic complexity), and these cross-trial comparisons come from small subgroup analyses in most cases. Additionally, it is particularly challenging to interpret PFS between continuous administration of a cBTKi and time-limited therapy with Ven-O with which there is the potential for retreatment at progression to extend benefit. For these reasons, when the impact of a molecular risk factor on prognosis is different between a second-generation cBTKi and Ven-O, this does not establish a predictive role for guiding selection of therapy. The ongoing CLL17 study will compare the impact of Ven-O vs ibrutinib in the frontline setting but is not restricted to patients with del(17p)/TP53M.

Second-line therapy after a frontline cBTKi

This section describes panel recommendations for selecting second-line therapy after initial cBTKi. Figure 2A graphically summarizes recommendations.

Treatment algorithms for CLL or SLL. (1) Our approach adheres to the iwCLL guidelines 2018 for the initiation of therapy for CLL/SLL (refer to Section 1; supplemental Table 1); (2) for patients with CLL/SLL who discontinue therapy for intolerance, a treatment holiday can be considered (refer to Table 3); (3) when initial treatment of CLL/SLL is advised, we recommend targeted agents such as Ven with obinutuzumab, acalabrutinib w/wo obinutuzumab, or zanubrutinib (refer to Section 2); (4) for patients who are previously treated with Ven and an anti-CD20 mAb and later progress and require therapy, retreatment with Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb can be considered in patients who tolerated Ven well and whose disease did not progress within 1 year of stopping Ven (refer to Section 6.2); (5) for patients who require second-line treatment after frontline Ven and obinutuzumab, when retreatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb is not preferred, we recommend a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib; refer to Section 6.1); (6) for patients who discontinue a cBTKi because of intolerance and require further CLL/SLL treatment, an alternative second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) can be considered unless the reason for intolerance was a life- or organ-threatening condition (refer to Section 5.2); (7) for patients with CLL/SLL and 2 prior therapies including a cBTKi and Ven, when retreatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb or transitioning to an alternate cBTKi is not preferred, we recommend pirtobrutinib in most cases. In patients who are deemed good candidates, liso-cel should also be considered for this line or subsequent lines of therapy (refer to Section 8.1). See also Special Situations regarding use of pirtobrutinib for patients who require treatment after prior cBTKi with medical contraindication to Ven-based therapy (refer to Table 3). (8) For patients with CLL/SLL that is refractory to 3 prior therapies including Ven, a cBTKi, and pirtobrutinib, when treatment with liso-cel or participation in a clinical trial is not feasible or preferred, a PI3Kδ inhibitor should be considered (refer to Section 8.2); (9) referral to a CLL expert to discuss whether to pursue allogeneic stem cell transplant may be considered for patients with CLL/SLL who are refractory to at least 2 prior therapies including Ven and a cBTKi and obtained a remission to a subsequent therapy (refer to Section 8.3). (10) Clinical trials should be considered for all patients with CLL/SLL, when clinical trial participation is feasible and when the study objectives are well suited to the patient’s priorities (refer to Section 9). (11) Although the addition of obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib for frontline treatment of CLL/SLL may be associated with a longer PFS than acalabrutinib alone, the majority of the panel does not routinely add obinutuzumab because of potential added toxicity and the requirement for patients to receive intravenous infusion therapy; currently, the most common reason our panel adds obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib is the presence of uncontrolled autoimmune cytopenias (refer to Section 3). (12) Although rituximab with Ven is approved for patients with R/R CLL/SLL, the majority of the panel recommends obinutuzumab with Ven in this setting (refer to Section 5.1). ∗For patients previously treated with ibrutinib in place of acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, follow guidance as if they received a second-generation cBTKi.

Treatment algorithms for CLL or SLL. (1) Our approach adheres to the iwCLL guidelines 2018 for the initiation of therapy for CLL/SLL (refer to Section 1; supplemental Table 1); (2) for patients with CLL/SLL who discontinue therapy for intolerance, a treatment holiday can be considered (refer to Table 3); (3) when initial treatment of CLL/SLL is advised, we recommend targeted agents such as Ven with obinutuzumab, acalabrutinib w/wo obinutuzumab, or zanubrutinib (refer to Section 2); (4) for patients who are previously treated with Ven and an anti-CD20 mAb and later progress and require therapy, retreatment with Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb can be considered in patients who tolerated Ven well and whose disease did not progress within 1 year of stopping Ven (refer to Section 6.2); (5) for patients who require second-line treatment after frontline Ven and obinutuzumab, when retreatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb is not preferred, we recommend a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib; refer to Section 6.1); (6) for patients who discontinue a cBTKi because of intolerance and require further CLL/SLL treatment, an alternative second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) can be considered unless the reason for intolerance was a life- or organ-threatening condition (refer to Section 5.2); (7) for patients with CLL/SLL and 2 prior therapies including a cBTKi and Ven, when retreatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb or transitioning to an alternate cBTKi is not preferred, we recommend pirtobrutinib in most cases. In patients who are deemed good candidates, liso-cel should also be considered for this line or subsequent lines of therapy (refer to Section 8.1). See also Special Situations regarding use of pirtobrutinib for patients who require treatment after prior cBTKi with medical contraindication to Ven-based therapy (refer to Table 3). (8) For patients with CLL/SLL that is refractory to 3 prior therapies including Ven, a cBTKi, and pirtobrutinib, when treatment with liso-cel or participation in a clinical trial is not feasible or preferred, a PI3Kδ inhibitor should be considered (refer to Section 8.2); (9) referral to a CLL expert to discuss whether to pursue allogeneic stem cell transplant may be considered for patients with CLL/SLL who are refractory to at least 2 prior therapies including Ven and a cBTKi and obtained a remission to a subsequent therapy (refer to Section 8.3). (10) Clinical trials should be considered for all patients with CLL/SLL, when clinical trial participation is feasible and when the study objectives are well suited to the patient’s priorities (refer to Section 9). (11) Although the addition of obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib for frontline treatment of CLL/SLL may be associated with a longer PFS than acalabrutinib alone, the majority of the panel does not routinely add obinutuzumab because of potential added toxicity and the requirement for patients to receive intravenous infusion therapy; currently, the most common reason our panel adds obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib is the presence of uncontrolled autoimmune cytopenias (refer to Section 3). (12) Although rituximab with Ven is approved for patients with R/R CLL/SLL, the majority of the panel recommends obinutuzumab with Ven in this setting (refer to Section 5.1). ∗For patients previously treated with ibrutinib in place of acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, follow guidance as if they received a second-generation cBTKi.

For patients who require second-line treatment after frontline cBTKi, when use of an alternative cBTKi is not appropriate or preferred, we recommend Ven with an anti-CD20 mAb. Although rituximab with Ven is approved for patients with R/R CLL/SLL, the majority of the panel recommends obinutuzumab with Ven in this setting

Ven-rituximab is approved for R/R CLL/SLL based on the MURANO phase 3 trial of Ven plus rituximab vs bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) in R/R CLL/SLL, which demonstrated superior PFS compared with bendamustine-rituximab (54.7 vs 17.9 months; P < .0001).69,70 In MURANO, Ven is stopped after 2 years, with rituximab administered concurrently during the first 6 months. Importantly, MURANO included very few patients with prior cBTKi, and >95% were previously treated with chemoimmunotherapy. Single-arm prospective trials and real-world data sets have confirmed that Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb is effective after a cBTKi.71-75

The majority of the panel recommends Ven-O for R/R CLL/SLL with an obinutuzumab lead-in before the Ven ramp-up (CLL14 schedule) and 2 years of Ven (off-label; supplemental Table 3). This is based on extrapolations from the frontline setting, in which obinutuzumab is more effective than rituximab (supplemental Table 8).35,38,76 In CLL13, Ven-O was associated with higher rates of undetectable measurable residual disease (MRD) with a cutoff of ≤10−4 (MRD4) compared with FCR or bendamustine-rituximab in fit patients with CLL/SLL without del(17p)/TP53M, but Ven-rituximab was not.38 In CLL11, in which patients with CLL/SLL and coexisting conditions were randomized to receive chlorambucil alone, or chlorambucil with either obinutuzumab or rituximab, obinutuzumab was associated with prolonged OS compared with chlorambucil alone or chlorambucil with rituximab.76

When patients have disease progression on a cBTKi, abrupt discontinuation may precipitate rapid progression.77 Therefore, for patients with progression on a cBTKi, when Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb is started, we continue the cBTKi until there is evidence of clinical/laboratory evidence of response (may range from 1 week to 2 months; Table 3).

Special treatment situations

| Topic . | Consensus statement . | Justification and supporting literature . |

|---|---|---|

| When to consider a treatment holiday | For patients with CLL/SLL who discontinue therapy for intolerance, a treatment holiday can be considered. | This recommendation is based on the observation that among patients with CLL/SLL whose disease is responding to therapy, and who discontinue therapy for intolerance, some have durable treatment-free remissions. Little data exist to guide selection of patients for a treatment holiday. Our panel considers several factors, for example, duration of therapy and quality of response, in an effort to predict which patients will remain progression-free off therapy. In a single-arm study of elective ibrutinib discontinuation after ≥6 y of continuous therapy, most had decreased or stable disease after a ≥1-y treatment-free interval.78 The panel is also more inclined to consider a treatment holiday in patients without high-risk molecular features, based on posttreatment MRD kinetics data from MURANO suggesting faster MRD doubling in the presence of high-risk molecular features.79 |

| How to transition from a cBTKi to Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb | In patients with progressive disease on a cBTKi who are recommended Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb, the panel recommends a period of overlapping therapy, with the cBTKi generally stopped once there is evidence of disease control, which can range from 1 wk to 2 mo. | When CLL becomes resistant to a cBTKi, there are often subclones of resistant CLL cells and subclones of cells that are still responsive to the cBTKi. As such, abrupt discontinuation of a cBTKi without transition to another therapy can lead to rapid progression of CLL.77 Safety data are available for each approved cBTKi combined with Ven and an anti-CD20 mAb.80-82 We recommend initiating Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb before stopping the cBTKi, as a period of overlap can prevent rapid progression of disease. The cBTKi can be stopped once there is evidence of disease control (eg, reduction of lymphocyte count, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and/or CLL-related symptoms). This period of time can range from 1 wk to 2 mo. |

| How to administer Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb in the retreatment setting | When retreatment with Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb is recommended, the decision to add anti-CD20 and the optimal treatment length should be individualized to each patient. | Data are lacking regarding the best approach for Ven retreatment (Ven monotherapy or Ven combined with rituximab or obinutuzumab). In the largest series of Ven retreatment, Ven was administered as monotherapy (45.7%) or in combination with rituximab (28.2%), obinutuzumab (10.9%), ibrutinib (4.4%), or another agent (10.9%).83 When an anti-CD20 mAb is combined with Ven in the retreatment setting, the majority of the panel recommends obinutuzumab with Ven, which is initiated using a modified CLL14 schedule (refer to Section 5.2). Whether Ven should be stopped after 24 mo as in the MURANO trial or until progression or intolerance is unknown.69,70 An ongoing prospective study evaluating retreatment with Ven plus obinutuzumab after frontline treatment with the same regimen will provide prospective data using this strategy (ReVenG; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04895436). |

| When to consider off-label pirtobrutinib in Ven-naïve patients after a cBTKi | In a patient with a medical contraindication to Ven-based therapy, pirtobrutinib (off-label) may be considered in Ven-naïve patients after a cBTKi. | Pirtobrutinib is FDA approved for patients with CLL/SLL and ≥2 prior therapies including a cBTKi and Ven based on the BRUIN study.84,85 Importantly, the BRUIN study included Ven-naïve patients (n = 154) and a post hoc analysis demonstrated a 2-y PFS of 83.1%. Therefore, in the setting of a medical contraindication to Ven-based therapy, pirtobrutinib may be considered in Ven-naïve patients after a cBTKi. |

| Topic . | Consensus statement . | Justification and supporting literature . |

|---|---|---|

| When to consider a treatment holiday | For patients with CLL/SLL who discontinue therapy for intolerance, a treatment holiday can be considered. | This recommendation is based on the observation that among patients with CLL/SLL whose disease is responding to therapy, and who discontinue therapy for intolerance, some have durable treatment-free remissions. Little data exist to guide selection of patients for a treatment holiday. Our panel considers several factors, for example, duration of therapy and quality of response, in an effort to predict which patients will remain progression-free off therapy. In a single-arm study of elective ibrutinib discontinuation after ≥6 y of continuous therapy, most had decreased or stable disease after a ≥1-y treatment-free interval.78 The panel is also more inclined to consider a treatment holiday in patients without high-risk molecular features, based on posttreatment MRD kinetics data from MURANO suggesting faster MRD doubling in the presence of high-risk molecular features.79 |

| How to transition from a cBTKi to Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb | In patients with progressive disease on a cBTKi who are recommended Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb, the panel recommends a period of overlapping therapy, with the cBTKi generally stopped once there is evidence of disease control, which can range from 1 wk to 2 mo. | When CLL becomes resistant to a cBTKi, there are often subclones of resistant CLL cells and subclones of cells that are still responsive to the cBTKi. As such, abrupt discontinuation of a cBTKi without transition to another therapy can lead to rapid progression of CLL.77 Safety data are available for each approved cBTKi combined with Ven and an anti-CD20 mAb.80-82 We recommend initiating Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb before stopping the cBTKi, as a period of overlap can prevent rapid progression of disease. The cBTKi can be stopped once there is evidence of disease control (eg, reduction of lymphocyte count, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and/or CLL-related symptoms). This period of time can range from 1 wk to 2 mo. |

| How to administer Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb in the retreatment setting | When retreatment with Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb is recommended, the decision to add anti-CD20 and the optimal treatment length should be individualized to each patient. | Data are lacking regarding the best approach for Ven retreatment (Ven monotherapy or Ven combined with rituximab or obinutuzumab). In the largest series of Ven retreatment, Ven was administered as monotherapy (45.7%) or in combination with rituximab (28.2%), obinutuzumab (10.9%), ibrutinib (4.4%), or another agent (10.9%).83 When an anti-CD20 mAb is combined with Ven in the retreatment setting, the majority of the panel recommends obinutuzumab with Ven, which is initiated using a modified CLL14 schedule (refer to Section 5.2). Whether Ven should be stopped after 24 mo as in the MURANO trial or until progression or intolerance is unknown.69,70 An ongoing prospective study evaluating retreatment with Ven plus obinutuzumab after frontline treatment with the same regimen will provide prospective data using this strategy (ReVenG; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04895436). |

| When to consider off-label pirtobrutinib in Ven-naïve patients after a cBTKi | In a patient with a medical contraindication to Ven-based therapy, pirtobrutinib (off-label) may be considered in Ven-naïve patients after a cBTKi. | Pirtobrutinib is FDA approved for patients with CLL/SLL and ≥2 prior therapies including a cBTKi and Ven based on the BRUIN study.84,85 Importantly, the BRUIN study included Ven-naïve patients (n = 154) and a post hoc analysis demonstrated a 2-y PFS of 83.1%. Therefore, in the setting of a medical contraindication to Ven-based therapy, pirtobrutinib may be considered in Ven-naïve patients after a cBTKi. |

For patients who discontinue a cBTKi because of intolerance and require further CLL/SLL treatment, an alternative second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) can be considered unless the reason for intolerance was a life- or organ-threatening condition

Acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib have been evaluated in patients who are intolerant to a previous cBTKi, including in two prospective phase 2 trials (supplemental Table 7).86-88 In the acalabrutinib study, 30% of patients experienced recurrence of the intolerance event leading to ibrutinib discontinuation. In the zanubrutinib study, 40% experienced recurrence of the intolerance event leading to ibrutinib/acalabrutinib discontinuation. Recurrence of the same intolerance event led to discontinuation in just 1 patient (grade 2 diarrhea). When the same intolerance event recurred, most were with lower severity (67%-79%) and only 1 recurred with worse severity (increased liver function test; grade 2 on ibrutinib, then grade 3 on acalabrutinib). Importantly, because 21% to 30% of intolerance events recurred with unchanged severity after switching to acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, we do not advise an alternative second-generation cBTKi after life- or organ-threatening intolerance.

Second-line therapy after frontline Ven-O

This section describes panel recommendations for selecting second-line therapy after initial Ven-O. Figure 2B graphically summarizes recommendations.

For patients who require second-line treatment after frontline Ven-O, when retreatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb is not preferred, we recommend a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib)

Our panel recommends a second-generation cBTKi in the second-line setting after frontline Ven-O. Given the earlier introduction of cBTKi in frontline treatment of CLL/SLL, very few patients in the R/R cBTKi trials had prior Ven. Among patients enrolled in the ELEVATE-RR and ALPINE trials (Section 3), <3% patients received prior Ven.42,43 Limited data exist to estimate cBTKi efficacy after frontline Ven-O, drawn mostly from small retrospective series. In one study, among 44 patients who were BTKi naïve and previously received Ven in the frontline (4%) or R/R (96%) setting, cBTKi had an ORR of 84% and median PFS of 32 months.89 In another series of 23 patients who previously received Ven, cBTKi therapy had an ORR of 91% and median PFS of 34 months.90 These data support the use of BTKi after Ven-based therapy, and the panel recommends use of a second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) over ibrutinib (Section 3).

For patients previously treated with Ven and an anti-CD20 mAb and who later have disease progression and require therapy, retreatment with Ven w/wo anti-CD20 mAb can be considered in patients who tolerated Ven well and whose disease did not progress within 1 year of stopping Ven

Because Ven with obinutuzumab or rituximab are time-limited regimens, most patients with CLL/SLL discontinue Ven because of completion of planned therapy and are not resistant to Ven. In patients with subsequent disease progression who require therapy, if Ven was previously well tolerated, retreatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb can be considered. Whether to add an anti-CD20 mAb, and the optimal treatment length, should be individualized to each patient, as described in Table 3.

Venetoclax retreatment is supported by small data sets demonstrating frequent responses in patients requiring subsequent therapy.79,83,91 The largest is a retrospective multicenter analysis of 46 patients previously treated with Ven-based therapy, who later had disease progression and received a second course of Ven.83 Venetoclax retreatment was associated with an ORR of 80% and median PFS of 25 months. Notably, only 9% (4/46) received Ven retreatment after frontline Ven-based therapy, and the most common retreatment approach was Ven monotherapy (45.7%), thus these data might underestimate its efficacy. We await long-term follow-up and retreatment data from the frontline CLL14 and CLL13 studies and the ongoing ReVenG trial to refine this strategy, which includes cohorts who experienced 1 to 2 years and ≥2 years treatment-free intervals to identify the optimal duration of remission after treatment cessation when considering Ven retreatment.92

Although there are no clear data guiding patient selection for Ven retreatment, previous Ven tolerability and the length of time from completing prior Ven are likely important. We reserve Ven retreatment for patients with ≥1 year duration of response off treatment after prior Ven. This recommendation is based on MRD analyses in patients receiving frontline Ven-O, which suggested that (1) progression occurred earlier in patients with end-of-treatment detectable MRD (MRD4); and (2) among patients with detectable MRD4, 50% already had a rising CLL cell count.37 These data suggest an association between early progression and subclinical resistance to Ven, and that patients with longer treatment-free remissions, that is, ≥1- to 2-year duration of response after discontinuing Ven, are more likely to benefit from Ven retreatment.

Second-line therapy after other therapies

Prior cytotoxic chemotherapy

Although we advise against traditional chemoimmunotherapy in CLL/SLL, we continue to see patients who require treatment for relapsed CLL/SLL who have only received prior chemoimmunotherapy. When a patient with CLL/SLL has only received prior chemoimmunotherapy and requires subsequent therapy, we recommend use of second-generation cBTKi (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) or Ven with an anti-CD20 mAb as described in Sections 6.1 and 5.1, respectively. Section 4 describes how to choose between a cBTKi or Ven-O for treatment-naïve patients with CLL/SLL and can be extrapolated here.

Prior therapy with a cBTKi and BCL2i w/wo obinutuzumab

Ibrutinib-Ven is approved in Europe and the United Kingdom based on the GLOW trial41 and others have received initial therapy with a cBTKi and B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor (BCL2i) w/wo obinutuzumab through participation in clinical trials. The optimal second-line therapy approach for these patients is undefined. However, in the CAPTIVATE phase 2 trial of fixed-duration ibrutinib-Ven in patients with treatment-naïve CLL, ibrutinib retreatment had an ORR of 86% (19/22) and remissions appeared durable.93 Given these limited data, if the cBTKi-BCL2i regimen was stopped in an ongoing response, second-line therapy options include either a second-generation cBTKi, or treatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb (as described in Section 6.2). Alternatively, in patients who are primary refractory to a cBTKi-BCL2i combination, additional workup may be necessary to exclude Richter transformation (Table 1) before considering subsequent treatment of CLL/SLL (see Section 8).

Treatment sequencing after ≥2 therapies including Ven and a cBTKi

This section describes panel recommendations for therapy selection in patients with ≥2 prior therapies including Ven and a cBTKi. Transitioning to an alternate second-generation cBTKi (Section 6.2) or retreatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb (Section 5.2) may also be reconsidered. Figure 2 graphically summarizes panel recommendations.

For patients with CLL/SLL and ≥2 prior therapies including a cBTKi and Ven, when retreatment with Ven w/wo an anti-CD20 mAb or transitioning to an alternate cBTKi is not preferred, we recommend pirtobrutinib in most cases. In patients who are deemed good candidates, lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) should also be considered for this line or subsequent lines of therapy

Pirtobrutinib

The noncovalent BTKi pirtobrutinib is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for patients with CLL/SLL and ≥2 prior therapies including a cBTKi and Ven based on the BRUIN study.84,85 In this study, patients with prior cBTKi and Ven treatment (n = 128) who received the recommended dose of pirtobrutinib at 200 mg orally daily until progression or intolerance had an ORR of 80% (complete response rate of 0%) with a median PFS of 16 months, without a plateau in the PFS curve.84,94 Notably, pirtobrutinib was very well tolerated with reported rates of any grade diarrhea, fatigue, cough, and contusion as 37%, 28%, 27%, and 26%, respectively. Grade ≥3 adverse events were limited, with the most common being neutropenia in 28%, and it should be noted that many patients were neutropenic at baseline and there were very limited cases of febrile neutropenia. Nonhematologic grade ≥3 adverse events were rare, including typical BTKi adverse events such as hypertension (4%) and atrial fibrillation (2%). Given that CLL is most commonly diagnosed during the seventh decade and many patients have additional medical comorbidities, the limited toxicity and ease of administration are key considerations in recommending pirtobrutinib therapy in most cases in which patients need additional treatment after cBTKi and Ven.

Liso-cel

The anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, liso-cel, is FDA approved for patients with CLL/SLL and ≥2 prior therapies including a cBTKi and Ven based on the TRANSCEND-CLL 004 phase 1-2 trial of liso-cel in R/R CLL/SLL.95,96 In this study, patients with prior cBTKi and Ven treatment (n = 50) who received liso-cel had an ORR of 44% (complete response rate of 20%) and the median PFS was 11.9 months. In patients who achieved complete remission (CR; 20%), the median PFS was not reached with no relapses detected after 2 years of follow-up, albeit with very small sample size. In patients who achieved partial remission (PR; 24%), the median PFS was 26 months. There are limited data available to help predict which patients are most likely to achieve CR/PR. In an exploratory analysis from the TRANSCEND-CLL 004 trial, del(17p) or TP53M, unmutated IGHV, and increased karyotypic complexity were not associated with the likelihood of achieving response to liso-cel. Rather, response to liso-cel was associated with pretreatment variables indicating lower pretreatment disease burden (ie, lower tumor measurements, β2-microglobulin, and BALL score [includes β2-microglobulin, hemoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase, and time from initiation of prior therapy]).19

Logistically, patients are instructed to stay in close proximity of the chimeric antigen receptor T-cell treatment center for 30 days, and many require inpatient hospitalization. Cytokine release syndrome and neurological events occurred in 85% (8% grade ≥3) and 45% (19% grade ≥3) of patients, respectively. Although cytokine release syndrome/neurological events typically occur within the first 1 to 4 weeks, long-term toxicities including prolonged cytopenias (54%), grade ≥3 infections (18%), and hypogammaglobulinemia (15%) were frequent, albeit in a population enriched for prior traditional chemoimmunotherapy (89%). Liso-cel is a relatively higher-risk, higher-reward option, with long-term remissions observed in 20% of patients. This must be balanced against significant associated toxicities, which are typically seen during the first few weeks after liso-cel infusion. Although liso-cel can be administered to older patients, ideal candidates are younger and medically fit enough to tolerate the upfront toxicity of the regimen, and for those who prefer aggressive and potentially definitive, time-limited therapy.

Pirtobrutinib vs liso-cel

Pirtobrutinib and liso-cel are FDA approved in the same population (CLL/SLL with 2 prior therapies including a cBTKi and Ven). Randomized data are needed to determine whether pirtobrutinib or liso-cel is preferred. We recommend pirtobrutinib in most cases, given its ease of administration and favorable toxicity profile, and because we currently cannot predict patients with CLL/SLL who will achieve durable remissions with liso-cel. However, some patients will prioritize a potentially definitive, time-limited therapy, especially those who are younger and medically fit, and these patients may prefer liso-cel. Finally, we recognize that pirtobrutinib has a median PFS of only 16 months, making the selection of pirtobrutinib or liso-cel one of treatment sequencing for most patients.

Bridging therapy before liso-cel

Although liso-cel is administered to patients with active disease including those with high disease burden, bridging therapy is often necessary as a palliative measure during liso-cel manufacturing. In pirtobrutinib-naïve patients, pirtobrutinib is an excellent option for bridging therapy, which may reduce disease burden before liso-cel administration, so may be started in parallel with referral for liso-cel. In pirtobrutinib-exposed patients, other bridging therapies can be considered in consultation with a CLL expert and liso-cel provider.

For patients with CLL/SLL that is refractory to 3 prior therapies including Ven, a cBTKi, and pirtobrutinib, when treatment with liso-cel or participation in a clinical trial is not feasible or preferred, a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-δ (PI3Kδ) inhibitor should be considered

The PI3Kδ inhibitors duvelisib and idelalisib w/wo rituximab were FDA approved based on randomized trials showing prolonged PFS compared with an anti-CD20 mAb.97-99 PI3Kδ inhibitors have an unfavorable toxicity profile, including severe immune-mediated toxicities including colitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis, and severe infections. The approved PI3Kδ inhibitors also have limited efficacy in CLL/SLL. The pivotal trials were completed before wide availability of cBTKi and Ven. In a subsequent retrospective series, the median PFS with PI3Kδ inhibitor therapy was only 5 months among patients with prior cBTKi and Ven (n = 17).89 In rare instances that a PI3Kδ inhibitor is administered, we use the PI3Kδ inhibitor white paper on managing toxicity.100 We recommend engaging a provider experienced in monitoring for, and managing, PI3Kδ inhibitor toxicities.

Referral to a CLL expert to discuss whether to pursue allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-SCT) may be considered for patients with CLL/SLL who are refractory to at least 2 prior therapies including Ven and a cBTKi and who obtained a remission to a subsequent therapy