TO THE EDITOR:

Infections remain a significant concern in the treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM), particularly with the advancements in therapies targeting B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) on plasma cells.1 Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have shown the highest response rate and longest progression-free survival within the different BCMA-directed therapies. Currently, 2 BCMA-targeting CAR T-cell therapies are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, with many others are in development.2-6 As reported recently by Cordas dos Santos et al, among 1193 patients treated with BCMA CAR T cells including 457 outside of clinical trials, 95 nonrelapse deaths were observed (8%), with more than half attributed to infections.7 Only in one-third of these infection-related deaths the pathogen was reported.

Given the increasing use of BCMA CAR T cells, understanding the risk, nature, and timing of infectious complications is crucial, especially in a patient population already highly susceptible to infections. However, data on infections from clinical trials are often incompletely reported and real-world data are scarce. Recommendations from scientific societies rather reflect expert opinion extrapolated from other high-risk populations than evidence-based decisions.8,9

In this study, we performed a retrospective, multicenter real-world analysis to assess characteristics, incidence, and risk factors of infectious complications in BCMA-directed CAR T cells in RRMM. Data to assess infections in BCMA-targeting treatment recipients up to 200 days after CAR T-cell therapy were collected at 4 German university hospitals. We included adult patients with a diagnosis of RRMM treated with in-label BCMA-targeting CAR T cells outside of clinical trials. Prophylaxis with cotrimoxazole and valacyclovir was administered for 6 months after treatment in most patients (Table 1). No antibacterial or antifungal prophylaxis was used during neutropenia. Tocilizumab was administered in case of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) grade ≥2 or grade 1 with continuous fever. High-dose corticosteroids were used if any-grade immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) or CRS grade ≥2 occurred until resolution of symptoms. Immunoglobulin G levels were assessed monthly after CAR T-cell therapy. Patients received prophylactic substitution of monthly immunoglobulins if immunoglobulin G level was <4 g/L or as secondary prophylaxis in case of a major infection (requirement of antibiotic therapy). This was continued till immunoglobulin values recovered.

Patient characteristics

| . | Idecabtagene vicleucel (n = 42) . | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (n = 38) . | Overall (N = 80) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Mean (SD) | 65.8 (7.95) | 64.7 (7.92) | 65.3 (7.90) |

| Median (min, max) | 66.0 (41.0, 80.0) | 65.0 (43.0, 80.0) | 66.0 (41.0, 80.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 24 (57.1%) | 25 (65.8%) | 49 (61.3%) |

| Female | 18 (42.9%) | 13 (34.2%) | 31 (38.8%) |

| CRS | |||

| CRS 1 | 27 (64.3%) | 15 (39.5%) | 42 (52.5%) |

| CRS 2 | 8 (19.0%) | 17 (44.7%) | 25 (31.3%) |

| CRS 3 | 5 (11.9%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (6.3%) |

| None | 2 (4.8%) | 6 (15.8%) | 8 (10.0%) |

| ICANS | |||

| ICANS 1 | 7 (16.7%) | 3 (7.9%) | 10 (12.5%) |

| ICANS 2 | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| None | 35 (83.3%) | 34 (89.5%) | 69 (86.3%) |

| Tocilizumab | |||

| Yes | 38 (90.5%) | 31 (81.6%) | 69 (86.3%) |

| Dexamethasone | |||

| Yes | 20 (25.0%) | 21 (26.3%) | 41 (51.3%) |

| No. of prior therapies | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.14 (2.65) | 6.37 (2.99) | 6.78 (2.82) |

| Median (min, max) | 7.00 (2.00, 14.0) | 6.00 (2.00, 14.0) | 6.50 (2.00, 14.0) |

| Infection 30 d before CAR T cells | |||

| Yes | 14 (33.3%) | 4 (10.5%) | 18 (22.5%) |

| No | 28 (66.7%) | 34 (89.5%) | 62 (77.5%) |

| Antimicrobial prophylaxis | |||

| Double (valacyclovir/cotrimoxazole) | 37 (88.1%) | 29 (76.3%) | 66 (82.5%) |

| Single (valacyclovir) | 0 (0%) | 6 (15.8%) | 6 (7.5%) |

| Any infection after CAR T cells | |||

| Yes | 28 (66.7%) | 29 (76.3%) | 57 (71.3%) |

| . | Idecabtagene vicleucel (n = 42) . | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (n = 38) . | Overall (N = 80) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Mean (SD) | 65.8 (7.95) | 64.7 (7.92) | 65.3 (7.90) |

| Median (min, max) | 66.0 (41.0, 80.0) | 65.0 (43.0, 80.0) | 66.0 (41.0, 80.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 24 (57.1%) | 25 (65.8%) | 49 (61.3%) |

| Female | 18 (42.9%) | 13 (34.2%) | 31 (38.8%) |

| CRS | |||

| CRS 1 | 27 (64.3%) | 15 (39.5%) | 42 (52.5%) |

| CRS 2 | 8 (19.0%) | 17 (44.7%) | 25 (31.3%) |

| CRS 3 | 5 (11.9%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (6.3%) |

| None | 2 (4.8%) | 6 (15.8%) | 8 (10.0%) |

| ICANS | |||

| ICANS 1 | 7 (16.7%) | 3 (7.9%) | 10 (12.5%) |

| ICANS 2 | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| None | 35 (83.3%) | 34 (89.5%) | 69 (86.3%) |

| Tocilizumab | |||

| Yes | 38 (90.5%) | 31 (81.6%) | 69 (86.3%) |

| Dexamethasone | |||

| Yes | 20 (25.0%) | 21 (26.3%) | 41 (51.3%) |

| No. of prior therapies | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.14 (2.65) | 6.37 (2.99) | 6.78 (2.82) |

| Median (min, max) | 7.00 (2.00, 14.0) | 6.00 (2.00, 14.0) | 6.50 (2.00, 14.0) |

| Infection 30 d before CAR T cells | |||

| Yes | 14 (33.3%) | 4 (10.5%) | 18 (22.5%) |

| No | 28 (66.7%) | 34 (89.5%) | 62 (77.5%) |

| Antimicrobial prophylaxis | |||

| Double (valacyclovir/cotrimoxazole) | 37 (88.1%) | 29 (76.3%) | 66 (82.5%) |

| Single (valacyclovir) | 0 (0%) | 6 (15.8%) | 6 (7.5%) |

| Any infection after CAR T cells | |||

| Yes | 28 (66.7%) | 29 (76.3%) | 57 (71.3%) |

Max, maximum; min, minimum; SD, standard deviation.

This study was approved by the institutional ethics board of the University of Cologne registered under 24-1201-retro and approved by the institutional review board of University of Cologne. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. It was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients had an informed consent to the use of their anonymous data when admitted for CAR T-cell therapy.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Infections were reported in 57 patients (71.3%; Table 2). Most patients (82.5%) received anti-infective prophylaxis as described above.

Infections in BCMA-directed CAR T-cell recipients

| . | Idecabtagene vicleucel (n = 28) . | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (n = 29) . | Overall (n = 57) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade of infection | |||

| Outpatient | 10 (35.7%) | 8 (27.6%) | 18 (31.6%) |

| Inpatient | 11 (39.3%) | 8 (27.6%) | 19 (33.3%) |

| ICU | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Death | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.3%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| Type of infection | |||

| Bacterial | 10 (39.3%) | 9 (31.0%) | 19 (35.1%) |

| Viral | 17 (60.7%) | 19 (65.5%) | 36 (63.2%) |

| Fungal | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (3.4%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Pathogens: bacterial | |||

| Escherichia coli | 1 (3.6%) | 4 (13.8%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.5%) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (3.4%) | 2 (3.5%) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Ruminococcus gnavus | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (3.4%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Pathogens: viral | |||

| Adenovirus | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| CMV | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.3%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| HSV | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Influenza A | 3 (10.7%) | 1 (3.4%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| Norovirus | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Parainfluenza | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (6.9%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Rhinovirus | 2 (7.1%) | 3 (10.3%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| RSV | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Sapovirus | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 5 (17.9%) | 5 (17.2%) | 10 (17.5%) |

| Pathogens: fungal | |||

| Aspergillus spp. | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.5%) |

| Candida albicans | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Type of pathogen | |||

| Gram-negative bacteria | 6 (21.4%) | 6 (20.7%) | 12 (19.3%) |

| Gram-positive bacteria | 5 (17.9%) | 2 (6.9%) | 7 (12.3%) |

| Respiratory virus | 14 (50.0%) | 14 (48.3%) | 28 (49.1%) |

| Herpesviridae | 2 (7.1%) | 3 (10.3%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Other viruses | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Mold fungus | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Yeast fungus | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Unidentified pathogen | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Type of infection | |||

| Bloodstream infection | 3 (10.7%) | 4 (13.8%) | 7 (12.3%) |

| Diverticulitis | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Enteritis | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (3.4%) | 2 (3.5%) |

| Otitis | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Virus reactivation | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.3%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| Respiratory tract infection | 15 (53.6%) | 15 (51.7%) | 30 (52.6%) |

| Oral thrush | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Stomatitis | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 4 (14.3%) | 1 (3.4%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Disseminated infection | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Time from infusion to first infection, d | |||

| Mean (SD) | 50.4 (55.0) | 58.1 (55.4) | 54.3 (54.9) |

| Median (min, max) | 33.5 (1.00, 200) | 40.0 (0, 190) | 38.5 (0, 200) |

| Timing of first infection | |||

| Early (up to 30 d) | 15 (53.6%) | 13 (44.8%) | 28 (49.1%) |

| Late (after 30 d) | 15 (53.6%) | 17 (58.6%) | 32 (56.1%) |

| Duration of first infection | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.1 (16.6) | 13.3 (12.0) | 13.7 (14.4) |

| Median (min, max) | 9.50 (3.00, 92.0) | 10.0 (0, 60.0) | 10.0 (0, 92.0) |

| Neutropenia during first infection | |||

| No | 13 (46.4%) | 17 (58.6%) | 30 (52.6%) |

| Yes | 17 (60.7%) | 8 (27.6%) | 25 (43.9%) |

| Aplasia | 0 (0%) | 5 (17.2%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Hospitalization because of infection | |||

| Hospitalization | 8 (28.6%) | 8 (27.6%) | 16 (28.1%) |

| ICU | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.3%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| >1 infection episode | |||

| Yes | 3 (10.7%) | 4 (13.8%) | 7 (12.3%) |

| . | Idecabtagene vicleucel (n = 28) . | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (n = 29) . | Overall (n = 57) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade of infection | |||

| Outpatient | 10 (35.7%) | 8 (27.6%) | 18 (31.6%) |

| Inpatient | 11 (39.3%) | 8 (27.6%) | 19 (33.3%) |

| ICU | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Death | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.3%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| Type of infection | |||

| Bacterial | 10 (39.3%) | 9 (31.0%) | 19 (35.1%) |

| Viral | 17 (60.7%) | 19 (65.5%) | 36 (63.2%) |

| Fungal | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (3.4%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Pathogens: bacterial | |||

| Escherichia coli | 1 (3.6%) | 4 (13.8%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.5%) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (3.4%) | 2 (3.5%) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Ruminococcus gnavus | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (3.4%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Pathogens: viral | |||

| Adenovirus | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| CMV | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.3%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| HSV | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Influenza A | 3 (10.7%) | 1 (3.4%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| Norovirus | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Parainfluenza | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (6.9%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Rhinovirus | 2 (7.1%) | 3 (10.3%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| RSV | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Sapovirus | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 5 (17.9%) | 5 (17.2%) | 10 (17.5%) |

| Pathogens: fungal | |||

| Aspergillus spp. | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.5%) |

| Candida albicans | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Type of pathogen | |||

| Gram-negative bacteria | 6 (21.4%) | 6 (20.7%) | 12 (19.3%) |

| Gram-positive bacteria | 5 (17.9%) | 2 (6.9%) | 7 (12.3%) |

| Respiratory virus | 14 (50.0%) | 14 (48.3%) | 28 (49.1%) |

| Herpesviridae | 2 (7.1%) | 3 (10.3%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Other viruses | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Mold fungus | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Yeast fungus | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Unidentified pathogen | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (6.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Type of infection | |||

| Bloodstream infection | 3 (10.7%) | 4 (13.8%) | 7 (12.3%) |

| Diverticulitis | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Enteritis | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (3.4%) | 2 (3.5%) |

| Otitis | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Virus reactivation | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.3%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| Respiratory tract infection | 15 (53.6%) | 15 (51.7%) | 30 (52.6%) |

| Oral thrush | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Stomatitis | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 4 (14.3%) | 1 (3.4%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Disseminated infection | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Time from infusion to first infection, d | |||

| Mean (SD) | 50.4 (55.0) | 58.1 (55.4) | 54.3 (54.9) |

| Median (min, max) | 33.5 (1.00, 200) | 40.0 (0, 190) | 38.5 (0, 200) |

| Timing of first infection | |||

| Early (up to 30 d) | 15 (53.6%) | 13 (44.8%) | 28 (49.1%) |

| Late (after 30 d) | 15 (53.6%) | 17 (58.6%) | 32 (56.1%) |

| Duration of first infection | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.1 (16.6) | 13.3 (12.0) | 13.7 (14.4) |

| Median (min, max) | 9.50 (3.00, 92.0) | 10.0 (0, 60.0) | 10.0 (0, 92.0) |

| Neutropenia during first infection | |||

| No | 13 (46.4%) | 17 (58.6%) | 30 (52.6%) |

| Yes | 17 (60.7%) | 8 (27.6%) | 25 (43.9%) |

| Aplasia | 0 (0%) | 5 (17.2%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Hospitalization because of infection | |||

| Hospitalization | 8 (28.6%) | 8 (27.6%) | 16 (28.1%) |

| ICU | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.3%) | 4 (7.0%) |

| >1 infection episode | |||

| Yes | 3 (10.7%) | 4 (13.8%) | 7 (12.3%) |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; ICU, intensive care unit; max, maximum; min, minimum; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SD, standard deviation.

Among those who developed infections, 19 patients (33.3%) required hospitalization, 3 patients (5.3%) were admitted to the intensive care unit, and 4 patients (5.3%) died because of infection-related complications (Table 2). Neutropenia was present in 25 patients at the time of infection.

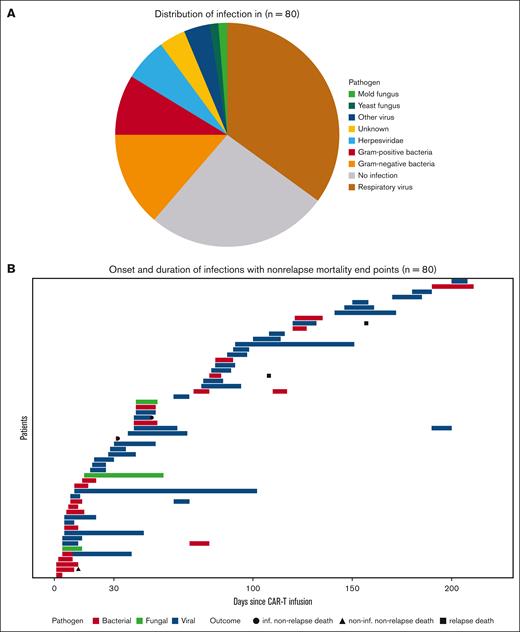

Viral infections were the most common (Figure 1A), comprising 45% of cases, with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (17.5%), parainfluenza (8.8%), rhinovirus (8.8%), and influenza A virus (7.0%) being the most frequent. Bacterial infections occurred in 35.1% of patients, with gram-negative pathogens in 11 cases and gram-positive in 7. Fungal infections were rare, with only 1 case of Candida albicans esophagitis and 2 cases of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (1 probable case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus spp. and 1 possible with unidentified fungal pathogen; classified along the current criteria of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism Expert Group on Nutrition in Cancer).10 The respiratory tract was the most frequent infection site (52.6%), followed by the bloodstream (12.3%) and urinary tract (8.8%). Infections were defined upon the combination of microbiological and clinical data (presence of fever).

Distribution and sequence of infections. (A) Pie chart showing the distribution of infections in treated patients (N = 80). (B) Swimmer plot showing onset, subtype, and duration of infections with nonrelapse mortality and relapse mortality as end points (N = 80).

Distribution and sequence of infections. (A) Pie chart showing the distribution of infections in treated patients (N = 80). (B) Swimmer plot showing onset, subtype, and duration of infections with nonrelapse mortality and relapse mortality as end points (N = 80).

As depicted in Figure 1B, 28 infection episodes occurred within the first 30 days after infusion, with 32 episodes occurring later. Bacterial infections predominantly occurred during the first 15 days, whereas viral infections presented later after CAR T-cell therapy. This difference was significant (Pearson χ2 test with Yates continuity correction: P = .02).

Infections remain a significant concern in this patient population, driven by the immunosuppressive effects of prior therapies, the CAR T-cell treatment itself, and the subsequent CRS and ICANS management, often involving corticosteroids and tocilizumab.11 Our data add to the growing body of literature on infection complications after CAR T-cell therapy.12 The overall infection rate of 71.3% observed in this cohort is consistent with published data.11,13 Bacterial infections were significantly higher early after treatment in our cohort. Especially those caused by gram-negative bacteria during neutropenia and associated with mucosal barrier damage 11 were identified in 25% of patients, higher than in previous studies.12 This emphasizes the early period as a high-risk window for infections in alignment with the nadir of neutrophils and lymphodepletion and the peak of CRS incidence entailing immunosuppressive treatment.11,13 The type of CAR T-cell product and its costimulatory domain also affect the risks of CRS, ICANS, and hematologic toxicity, indirectly affecting infection risks.

Beyond the initial 30 days after treatment, the risk of infection persists because of prolonged B-cell and plasma cell depletion caused by “on-target off-tumor” effects. Notably, viral infections were predominant, accounting for 45% of cases. Unlike bacterial infections, they were found to occur mainly beyond day 30 after infusion. Recent studies have highlighted viral infections as a leading cause of morbidity in immunosuppressed populations, particularly because of their susceptibility to community-acquired infections.14 Bacterial infections, primarily caused by gram-negative bacteria during periods of neutropenia and mucosal barrier damage, were identified in 25% of patients, a higher rate than previously reported. Fungal infections were rare, occurring at even lower rates than those reported in phase 3 clinical trials, suggesting that routine antifungal prophylaxis may not be necessary.15 The fact that 33.3% of patients with infections required hospitalization and 5.3% required intensive care unit care underlines the high impact of infections in this setting as shown previously.11,12 The 5% infection-related mortality (IRM) rate observed is within the range reported in the literature, emphasizing the lethal potential of infections in this vulnerable population. The overall nonrelapse mortality is 8.8% and in line with Cordas dos Santos et al who reported a nonrelapse mortality of 8.0% across all patients with myeloma, including patients enrolled in clinical trials who are considered to be less intensely pretreated and better monitored. We assume that improving diagnostic algorithms and management in case of infection as well as increasing experience with BCMA CAR T-cell therapy and its complications will contribute to lowering the mortality rate.

In total 31.6% of the occurring infections were vaccine preventable, at least regarding severity of disease, including infections by Haemophilus influenzae, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Given the profound immunosuppression associated with CAR T-cell therapy, vaccination strategies must be carefully considered. Vaccinations should ideally be given at least 2 weeks before CAR T-cell therapy to provide adequate time for an effective immune response.16,17 Among the vaccines recommended at this stage are the inactivated influenza vaccine, the pneumococcal vaccines (both PCV13 and PPSV23), hepatitis B vaccine, and the Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) vaccine. In contrast, live vaccines, such as the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine or varicella (chickenpox) vaccine, are generally contraindicated. After completing CAR T-cell therapy, vaccines can be administered earliest from day 42 on allowing time for immune reconstitution.18 Given very low vaccination rates in target groups in Germany,19 our data emphasize not only the need for promoting the development of optimized vaccines and vaccination schedules but also for rising awareness among patients and treating physicians.

This real-world data set comprises several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study, and some data were missing. Second, some infection prevention practices as well as diagnostic standards are heterogeneous at the participating centers and developed over the time of the inclusion period. Moreover, we included infections after CAR T-cell therapy only until the next treatment (in case of relapse of MM after CAR T-cell therapy, which occurred in 30% of patients). The first patients were treated during the COVID-19 pandemic under extraordinary circumstances. We did not evaluate the impact of immunoglobulin replacement in this study because of variations in IV immunoglobulin use over the study period.

Our data emphasize the critical need for comprehensive infection surveillance and management protocols in patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy. The observed infection patterns and outcomes reinforce the importance of prevention strategies and the need for interdisciplinary treatment by hematologists and infectious disease specialists.

IRM remains a major threat in patients receiving BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy despite the comparably low death rate in our cohort. In-depth reporting of infections in phase 3 trials for novel therapies in MM should be standardized and thoroughly included in the final analysis in order to adapt infection prevention strategies and diagnostic algorithms to mitigate IRM.

Contribution: T.R., S.C.M., and J.S. implemented the research, conducted collection and analysis of patient data, and authored the manuscript; D.S. performed statistical analyses, supervised by T.R., S.C.M., and J.S.; C.S., U.H., and O.A.C. supervised the project; and B.-N.B., M.C., T.A.W.H., F.S., M.H., C.S., U.H., G.K., and O.A.C. coauthored the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.S. reports grants or contracts from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research Medical Faculty of the University of Cologne, from Basilea and Noscendo (payments were made to his institution); received consulting fees from Gilead, Mundipharma, Alvea Vax, and Micron Research; received payments or honoraria for presentations, speaker's bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events by AbbVie, Hikma, Gilead, and Pfizer; and reports receipt of equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts, or other services payments made to the institution by Basilea. O.A.C. reports grants or contracts from Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, Cidara, Deutsches Zentrum für Infektionsforschung (DZIF), European Union-Directorate General for Research and Innovation, F2G, Gilead, Medpace, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma, Octapharma, Pfizer, and Scynexis; reports consulting fees from AbbVie, AiCuris, Basilea, Biocon, Boston Strategic Partners, Cidara, Seqirus, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, IQVIA, Janssen, Matinas, Medpace, Menarini, Molecular Partners, Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium, Mundipharma, Noxxon, Octapharma, Pardes, Partner Therapeutics, Pfizer, Pharmaceutical Solutions International, Scynexis, Seres, Shionogi, and Prime Meridian Group; reports speaker and lecture honoraria from Abbott, AbbVie, Akademie für Infektionsmedizin, Al-Jazeera Pharmaceuticals/Hikma, amedes, AstraZeneca, Deutscher Ärzteverlag, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Grupo Biotoscana/United Medical/Knight, Ipsen Pharma, Medscape/WebMD, MedUpdate, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Moderna, Mundipharma, Noscendo, Paul-Martini-Stiftung, Pfizer, Sandoz, Seqirus, Shionogi, STREAMED UP, Touch Independent, and Vitis; received payment for expert testimony for Cidara; and reports participation on a data review committee, data safety monitoring board, and advisory board for Cidara, IQVIA, Janssen, MedPace, Pharmaceutical Solutions International, Pulmocide, and Vedanta Biosciences. S.C.M. received research grants by DZIF and the University Hospital of Cologne; and received honoraria as a consultant by Octapharma and as a speaker by Pfizer (none of these involved in the work presented). M.H. received research funding by Roche (paid to institution), AbbVie (paid to institution), Janssen (paid to institution), AstraZeneca (paid to institution), BeiGene (paid to institution), and Lilly (paid to institution). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sibylle C. Mellinghoff, Department I of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Cologne, University of Cologne, Kerpener Str 62, 50931 Cologne, Germany; email: Sibylle.mellinghoff@uk-koeln.de.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Sibylle C. Mellinghoff (sibylle.mellinghoff@uk-koeln.de).