Key Points

rs2814778-CC is only reproducibly associated with changes in white blood cell count and not with any disease outcomes.

Race is not an accurate predictor of Duffy-null–associated benign neutropenia; genetic screening of rs2814778 is needed.

Visual Abstract

A wealth of research focused on African American populations has connected rs2814778-CC (“Duffy-null”) to decreased neutrophil (neutropenia) and leukocyte counts (leukopenia). Although it has been proposed that this variant is benign, prior studies have shown that the misinterpretation of Duffy-null–associated neutropenia and leukopenia can lead to unnecessary bone marrow biopsies, inequities in cytotoxic and chemotherapeutic treatment courses, underenrollment in clinical trials, and other disparities. To investigate the phenotypic correlates of Duffy-null status, we conducted a phenome-wide association study across >1400 clinical conditions in All of Us, the Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Biobank, and the Million Veteran Program. This reveals that Duffy-null status is only reproducibly associated with changes in white blood cell count and not with any disease outcomes. Moreover, we find that Duffy-null–associated neutropenia is on average less severe than other neutropenia cases in All of Us. We also show that this genotype is present in considerable frequencies in All of Us populations that are genetically similar to African (68%) and Middle Eastern (14%) 1000 Genomes/Human Genome Diversity Project reference populations as well as those who identify with >1 race (12%), as Pacific Islander (7%), and as Hispanic (5%). Furthermore, we find that race is not an accurate predictor of Duffy-null status or associated benign neutropenia. Our research suggests that broad genetic screening of rs2814778 across all populations could provide a more robust and accurate understanding of white blood cell count and mitigate resulting health disparities.

Introduction

It has been well documented that individuals with African ancestry have lower average white blood cell count (WBC).1-6 Although neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of <1.5 × 103/μL, this classification was developed in populations with predominantly European ancestry.7,8 Historically benign ethnic neutropenia (BEN) has been used to describe chronic neutropenia without any increased risk of infection and is common in individuals with African, Caribbean, Middle Eastern, and West Indian ancestry.9-15

A large proportion of BEN cases have been attributed to the homozygous T to C substitution, rs2814778-CC, in the promoter of the human atypical chemokine receptor 1 gene (ACKR1), which abolishes a GATA1 erythroid transcription factor binding site causing loss of the Duffy antigen on the surface of red blood cells.8,16-24 However, ACKR1 is still expressed in other tissues, such as venular endothelial cells and cerebellar neurons25,26 Multiple modes of evidence support the hypothesis that the loss of Duffy on the surface of red blood cells confers resistance to Plasmodium vivax malaria, including rs2814778-CC’s high allele frequency in populations with ancestry from regions in which malaria has historically been endemic.8,27-30 The allele frequency of rs2814778-C varies substantially by population, with it being >90% in individuals recruited from West and sub-Saharan Africa, >50% through the Arabian Peninsula, 5% to 20% across India, and nearly absent in Europe.8

Recent studies indicate that the reduction in neutrophils in Duffy-null individuals does not compromise neutrophil effector functions, supporting the hypothesis that Duffy status should not increase risk of infection.31 Although it is unclear whether the lowered circulating neutrophil counts resulting from the Duffy-null genotype directly confers health impacts, issues with accurate and equitable medical care have been identified for the Duffy phenotype.32-42 For instance, under-recognition of the phenotypic effects of the Duffy-null genotype has resulted in the misattribution of low neutrophil counts, which has led to disproportionate rates of unnecessary bone marrow biopsies in Duffy-null individuals.41

Despite its impact on ANC, most evidence suggests that the genetic variant rs2814778 does not directly cause any relevant health effects.6,10,15,43 Here, we perform a phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) in large population-based cohorts with linked electronic health records (EHRs) to explore potential disease associations related to this variant. PheWAS systematically tests whether specific genetic variants are associated with any of thousands of human phenotypes, with a focus on case control disease traits, correcting for multiple testing across a large number of phenotypes.44 The All of Us (AoU) research platform provides a wealth of electronic health-based data and is particularly powerful for studying populations underrepresented in research such as individuals with ancestries from malaria-endemic regions. We performed a PheWAS using the AoU platform to investigate potential disease associations with rs2814778. We then performed a meta-analysis with results from the Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Biobank (BioVU) and the Department of Veteran Affairs Million Veteran Program (MVP) to confirm our results. Our findings provide additional evidence supporting the notion that this single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is likely clinically benign, despite its impacts on ANC, and should be taken into consideration when interpreting clinical blood cell measurements.

Methods

Study participant selection

The AoU program addresses the critical need for increased diversity in research by enrolling historically underrepresented groups such as: racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with low socioeconomic status, individuals with disability, individuals with less than a high school education, those that live in rural areas, or those that identify as a sexual or gender minority.45 For genetic similarity clustering in AoU, the gnomAD version 3.1–provided reference panel (using the 1000 Genomes/Human Genome Diversity Project [1000G/HGDP]) was used to train a random forest classifier using the first 16 genetic principal components (PCs). In this report, we refer to genetic similarity clusters based on the continental ancestry group reference panel to which the individuals in AoU show highest genetic similarity. We use the suffix “-like” to emphasize that these groupings are contingent on the specific individuals included in the reference panels. For analysis of allele frequencies both by genetic similarity to reference populations and by self-report race and ethnicity, allele frequencies were calculated from all individuals in AoU with whole-genome sequencing data (n = 245 394). For subsequent analyses, only those with whole-genome sequencing data, demographic data for the self-reported race and ethnicity analysis and sex/gender, an EHR length of >3 years, and at least 3 visit dates in their EHR were used (n = 99 409; release version 7.1, September 2023). Individuals having undergone dialysis or having received a bone marrow transplant were excluded from the analysis (n = 1095). Except for the PheWAS, individuals with phecodes for a lymphoproliferative disorder, a myeloproliferative disorder, congenital anemia, aplastic anemia, a hemoglobinopathy, HIV, end-stage renal disease, cirrhosis, or having undergone chemotherapy or a splenectomy were also excluded from all other analyses (n = 10 202; supplemental Figure 1) This mirrors exclusions made in previous blood cell genetics reports to account for conditions that would cause large acute or chronic differences in blood cell traits.44

Adjusted R2 models

Because AoU data are manually entered by physicians across the United States, we excluded nonphysiological blood cell counts that likely reflected testing errors or misreporting: ANC and WBC of <0.01 × 103/μL and >100 × 103/μL, respectively. We then took the median of laboratory measurements and inverse normalized the counts before association analyses. When running the linear regression with the ANC and WBC residuals as the outcome variable, we controlled for age at measurement, sex at birth/gender (cisgender male, cisgender female, and sex and/or gender minority), 10 genetic PCs, and number of measured neutrophil values. We also ran models including White, Black, Asian, >1 race, Middle Eastern, and unknown races, and Hispanic/non-Hispanic ethnicity as covariates (race and ethnicity models).

PheWAS

In AoU, we adopted the PheWAS pipeline developed by Ramirez et al46 and hosted on AoU as a demonstration workspace (“Demo - PheWAS Smoking”). Duffy status was coded under the recessive model in which rs2814778-CT individuals were considered to have the same phenotype as rs2814778-TT individuals.16,18,21 We used age at last phecode, sex at birth/gender (cisgender male, cisgender female, and sex and/or gender minority), 10 genetic PCs, record depth, visit frequency, race (White, Black, Middle Eastern, >1 race, Asian, Unknown), and Hispanic ethnicity as covariates. Record depth and visit frequency were included as covariates to account for biases, with individuals with longer medical follow-up or more frequent visits potentially being more likely to be classified as cases, irrespective of their actual disease status. AoU generated the first 16 genetic PCs using the hwe_normalized_pca function in Hail at the high-quality variant sites. Record depth was approximated by adding the number of visits in which an observation or condition code was logged in the EHR. We ran different sensitivity analyses using the presence of 1 or 2 phecodes as indication of disease status, not including race or ethnicity as covariates, in just individuals self-identifying as Black to control for differential diagnostic rates because of medical racism, and in just participants with African-like genetic similarity to control for population structure (supplemental Table 2B-H). In the main analysis, race and ethnicity were included as covariates and 2 instances of a phecode were used to define a case in all ancestry groups. Individuals with 1 phecode were not included as controls. We incorporated race and ethnicity as covariates in 1 of our models with the aim of mitigating bias in the attribution of diagnostic codes based on race as a social construct, minimizing associations with health outcomes stemming directly from racial prejudice and underrepresentation in medical training, and to control for the association between the extent of health care records with race.46,47

For the BioVU and MVP PheWAS and the corresponding meta-analysis, refer to supplemental Methods for further details.

Results

Demographics of Duffy variant allele frequencies in AoU

The AoU research platform is, to our knowledge, the largest single collection of genomic and health-based records in diverse populations accessible to academic researchers. This ancestral diversity makes it a powerful tool for studying the health effects of genetic variants with variable frequency in different genetic ancestries that may have been overlooked in previous studies because of heavy Eurocentric research bias.49,50 The homozygous rs2814778-CC Duffy-null genotype is 1 such variant whose effects on outcomes may have been missed because of its low frequency (0.01%) in populations of European-like ancestry. However, it is extremely common (68.44%) in 1000G/HGDP African-like populations in AoU. Moreover, analysis of population-specific allele frequencies in our US-based cohort reveals that this genotype is also prevalent in populations with Middle Eastern–like (13.91%) and admixed American–like (1.96%) genetic similarity to 1000G/HGDP reference populations and in US populations that identify with >1 race (11.41%), as Pacific Islander (6.92%), and as Hispanic (4.54%; Figure 1; supplemental Table 1A-B).

Duffy allele frequencies. Bar charts showing 100% stacked Duffy allele frequencies by (A) genetic similarity to 1000G/HGDP reference populations and (B) self-reported race and ethnicity. The number of individuals in each group is included in the categorical labels. In the self-reported race and ethnicity chart, some individuals may appear twice because of the independent nature of race and ethnicity (eg, some individuals identify as Hispanic and as Black). The unknown category reflects individuals that answered “I prefer not to answer,” or “None of these,” or skipped the self-identified race question in the AoU demographics survey.

Duffy allele frequencies. Bar charts showing 100% stacked Duffy allele frequencies by (A) genetic similarity to 1000G/HGDP reference populations and (B) self-reported race and ethnicity. The number of individuals in each group is included in the categorical labels. In the self-reported race and ethnicity chart, some individuals may appear twice because of the independent nature of race and ethnicity (eg, some individuals identify as Hispanic and as Black). The unknown category reflects individuals that answered “I prefer not to answer,” or “None of these,” or skipped the self-identified race question in the AoU demographics survey.

Duffy variant status is associated with WBC and ANC

Previous observations of low WBC and ANC in African American individuals have largely been attributed to the Duffy-null variant.18-24 For each WBC trait, individuals with at least 2 measurements were characterized by their genotype at rs2814778 and then the mean (±standard deviation) and median were calculated for each genotype. In AoU, both WBC and ANC differ significantly by rs2814778 (P < .0001; Table 1). Significant differences (P < .0001) were observed for all other WBC traits. Although for most blood cell traits, the counts were lower in the rs2814778-CC genotype, the opposite trend was observed for lymphocytes. Notably, this leads to a decreased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in Duffy-null individuals (supplemental Table 1C). The increased ANC observed in the heterozygotes disappears when this analysis is stratified by genetic similarity to 1000G/HGDP populations (supplemental Table 1D-J). Moreover, associations with blood cell traits remain when adjusting for sex/gender, age, number of blood measurements, and 10 genetic PCs (supplemental Table 1K). The strength of blood cell associations is strongly, but incompletely, attenuated when limiting our analyses to non–Duffy-null individuals (supplemental Table 1L).

Comparison of WBC and ANC by rs2814778

| . | rs2814778-TT . | rs2814778-CT . | rs2814778-CC . |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | |||

| Mean (± SD) (×103/µl) | 7.27 (2.14) | 8.29 (2.36) | 6.63 (2.05) |

| Median (×103/µl) | 6.905 | 8 | 6.3 |

| Number of individuals | 45 527 | 5 974 | 8 377 |

| Number of measurements | 727 448 | 114 347 | 152 969 |

| Mean (±SD) number of measurements per individual | 15.98 (24.22) | 19.14 (28.38) | 18.26 (34.49) |

| Median number of measurements per individual | 8 | 11 | 9 |

| ANC | |||

| Mean (±SD) (×103/µl) | 4.76 (1.99) | 5.38 (2.18) | 3.88 (1.86) |

| Median (×103/µl) | 4.35 | 5 | 3.5 |

| Number of individuals | 36 188 | 4 931 | 7 003 |

| Number of measurements | 419 261 | 64 866 | 96 576 |

| Mean (± SD) number of measurements per individual | 11.59 (18.57) | 13.15 (20.42) | 13.79 (27.98) |

| Median number of measurements per individual | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| . | rs2814778-TT . | rs2814778-CT . | rs2814778-CC . |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | |||

| Mean (± SD) (×103/µl) | 7.27 (2.14) | 8.29 (2.36) | 6.63 (2.05) |

| Median (×103/µl) | 6.905 | 8 | 6.3 |

| Number of individuals | 45 527 | 5 974 | 8 377 |

| Number of measurements | 727 448 | 114 347 | 152 969 |

| Mean (±SD) number of measurements per individual | 15.98 (24.22) | 19.14 (28.38) | 18.26 (34.49) |

| Median number of measurements per individual | 8 | 11 | 9 |

| ANC | |||

| Mean (±SD) (×103/µl) | 4.76 (1.99) | 5.38 (2.18) | 3.88 (1.86) |

| Median (×103/µl) | 4.35 | 5 | 3.5 |

| Number of individuals | 36 188 | 4 931 | 7 003 |

| Number of measurements | 419 261 | 64 866 | 96 576 |

| Mean (± SD) number of measurements per individual | 11.59 (18.57) | 13.15 (20.42) | 13.79 (27.98) |

| Median number of measurements per individual | 6 | 7 | 6 |

Mean WBC and ANC compared across rs2814778 in AoU. The mean (±SD) and median of each individuals’ median value are reported. The number of individuals as well as the number of measurements considered in each mean are indicated in the table.

SD, standard deviation.

Duffy variant status explains a larger portion of variance in WBC and ANC than race and ethnicity

To validate that the Duffy-null variant is responsible for low ANC and WBC in self-identified Black adults, we analyzed a larger, more diverse cohort (AoU). We used linear regression models in the AoU data set to assess the associations between self-identified race and ethnicity, Duffy status, and ANC and WBC levels. In the base model, we adjusted for age at median blood cell count, number of blood cell measurements taken, sex/gender, and 10 genetic PCs. Adding race and ethnicity to this model decreased the adjusted R2 (Figure 2). However, adding Duffy to the model approximately doubled the proportion of variance explained by the model for both ANC and WBC. These results indicate that Duffy is a much stronger driver of observed differences in ANC and WBC in AoU than self-identified race or ethnicity.

Relative contribution of race and ethnicity (R&E) vs Duffy to variance in ANC and WBC. Results from a linear regression analysis performed in AoU looking at the association of R&E and/or Duffy status as a predictor of WBC and ANC. The base model included age at median blood cell count, number of blood cell measurements taken, sex/gender, and 10 genetic PCs. Adjusted R2 was used to account for the number of independent variables included in each model.

Relative contribution of race and ethnicity (R&E) vs Duffy to variance in ANC and WBC. Results from a linear regression analysis performed in AoU looking at the association of R&E and/or Duffy status as a predictor of WBC and ANC. The base model included age at median blood cell count, number of blood cell measurements taken, sex/gender, and 10 genetic PCs. Adjusted R2 was used to account for the number of independent variables included in each model.

Mild neutropenia in Duffy-null individuals

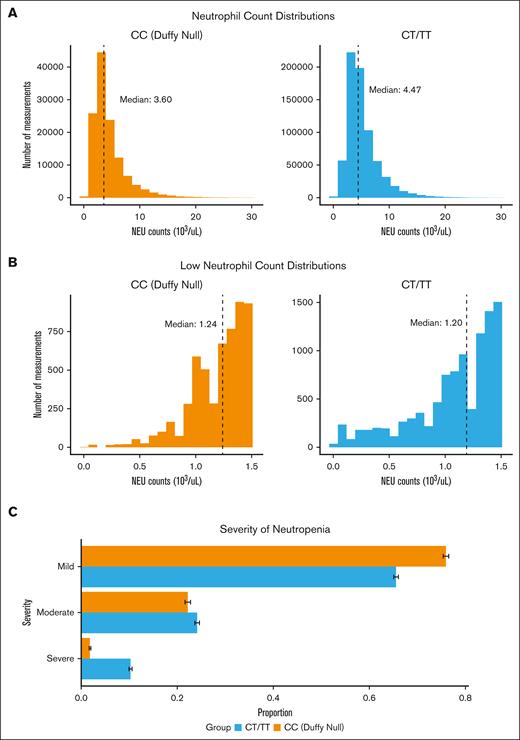

Duffy-null individuals have lower neutrophil counts on average, with 9.22% of Duffy-null individuals having at least 2 low ANCs compared with only 2.51% of non–Duffy-null individuals (Figure 3A). A recent report suggests that Duffy-null status may lead to more severe neutropenia than previously indicated; however, this study only included 66 Duffy-null individuals.51 Here, we examine the distribution of neutropenia severity by Duffy-null status in a much larger cohort. To this end, we compared histograms of low ANC (ANC < 1.5 × 103/μL) between non–Duffy-null individuals (n = 1783) and Duffy-null individuals (n = 1002; Figure 3B). Of the 2785 individuals with at least 2 low neutrophil counts, Duffy-null individuals had a significantly higher mean count (1.20 ± 0.26) than non–Duffy-null individuals (1.09 ± 0.38; P < .0001). Among these participants with low neutrophil counts, 10.3% of non–Duffy-null individuals had severe neutropenia (ANC < 0.5 × 103/μL), whereas only 1.8% of Duffy-null individuals had severe neutropenia (Figure 3C). The same trends are observed when restricting laboratory measurements to outpatient visits to control for acute changes due to illness and surgery (supplemental Figure 2). Although neutropenia was widely underdiagnosed (supplemental Figure 3), it is even more underdiagnosed in Duffy-null individuals (supplemental Table 1M).

Neutrophil (NEU) counts by Duffy status. (A) Histograms of ANC distributions for all NEU measurements. The ticked line indicates the median values for each group. (B) Histograms of ANC distributions for 2785 individuals with at least 2 low NEU counts (ANC < 1.5 × 103/μL) with and without the homozygous rs2814778-CT SNP. (C) Horizontal bar chart of low ANC binned by clinical classifications: mild (1.0 × 103/μL < ANC < 1.5 ×103/μL), moderate (0.5 × 103/μL < ANC < 1.0 × 103/μL), and severe (ANC < 0.5 × 103/μL).48

Neutrophil (NEU) counts by Duffy status. (A) Histograms of ANC distributions for all NEU measurements. The ticked line indicates the median values for each group. (B) Histograms of ANC distributions for 2785 individuals with at least 2 low NEU counts (ANC < 1.5 × 103/μL) with and without the homozygous rs2814778-CT SNP. (C) Horizontal bar chart of low ANC binned by clinical classifications: mild (1.0 × 103/μL < ANC < 1.5 ×103/μL), moderate (0.5 × 103/μL < ANC < 1.0 × 103/μL), and severe (ANC < 0.5 × 103/μL).48

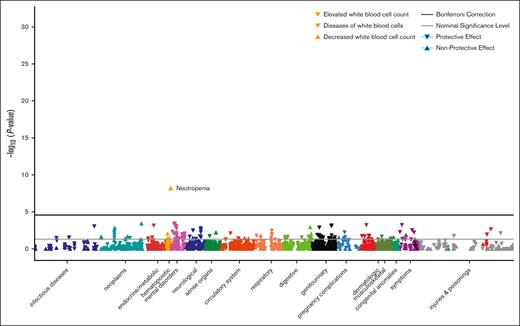

PheWAS of Duffy-null genotype

Although the Duffy-null genotype is associated with mildly decreased WBC and ANC, we wanted to assess whether it is associated with any diseases or conditions. Therefore, we ran a PheWAS testing for the association of this variant with the 1400 conditions that had at least 100 cases in AoU (Figure 4; supplemental Table 2A). This revealed that the homozygous rs2814778-CC genotype is only reproducibly associated with changes in WBC and a decrease in diseases of WBCs (supplemental Table 2B-H). These results align with recent findings in the MVP and AoU.52,53 Importantly, in AoU, we also find that the Duffy-null genotype was not associated with phenotypes associated with clinically significant neutropenia such as sepsis, pneumonia, abscesses, or diarrhea (supplemental Table 2A), or with infectious disease even when aggregating all of the phecodes in this category (P = .20; across 33 543 infectious disease cases and 65 856 controls).54 The absence of any other disease associations strengthens previous hypotheses that this variant is generally benign, at least for common diseases, which we are well-powered to assess for associations within a population-based cohort such as AoU (supplemental Table 2N). To confirm that the heterozygote genotype does not have phenotypic consequences, we also ran a PheWAS under the additive model and a PheWAS directly comparing rs2814778-CT and rs2814778-TT (supplemental Table 2I-J). We also performed more stringent analyses using REGENIE to confirm our results that met our significance threshold in AoU while controlling for potential statistical inflation due to unbalanced case-to-control ratios or cryptic relatedness (supplemental Table 2O).55

PheWAS of Duffy-null genotype. Manhattan plot of phenotype associations with the Duffy-null variant for individuals with demographic information, sufficient health records as defined in “Methods,” and at least 2 instances of the phecode. Phenotypes are colored by disease groups and are plotted as –log10 of the P value of the association. The black line represents the Bonferroni correction of significance.

PheWAS of Duffy-null genotype. Manhattan plot of phenotype associations with the Duffy-null variant for individuals with demographic information, sufficient health records as defined in “Methods,” and at least 2 instances of the phecode. Phenotypes are colored by disease groups and are plotted as –log10 of the P value of the association. The black line represents the Bonferroni correction of significance.

In addition to our PheWAS analysis in AoU, we conducted a meta-analysis incorporating data from the BioVU and MVP (supplemental Table 2M). The significant associations with WBC-related codes identified in the AoU PheWAS remained highly significant in this analysis, and a few nominally significant associations also emerged (supplemental Figure 4). Although sickle cell anemia was significant, it had discordant directions across BioVU and AoU and is a protected trait in MVP so could not be analyzed within that cohort. We believe the significance in the BioVU may be due, in part, to nonrandom sampling bias introduced by specialized care and patient recruitment. Specifically, Vanderbuilt University Medical Center, in alliance with Meharry Medical Center, leads a Center of Excellence in Sickle Cell Disease offering patients with sickle cell disease comprehensive specialized care. The causal variant for sickle cell anemia (rs334) also has a highly ancestry-differentiated allele frequency, driven by selective pressure from malaria, across reference populations in 1000G/HGDP. Residual confounding from population substructure with respect to genetic similarity may be occurring despite adjustment for genetic PCs. Diabetes mellitus and type 2 diabetes were also nominally significant within the meta-analysis. Effect sizes were driven by MVP and did not achieve significance in AoU or BioVU. We hypothesize that this observation may be because of residual confounding by G6PD variants, which are also high in frequency in 1000G/HGDP African-like AoU populations and are known to affect diabetes diagnostic rates. We suggest additional testing in future studies.

Discussion

A wealth of previous literature has connected the Duffy-null variant to decreased neutrophil counts.18-24 Our study extends these findings to a larger and more diverse cohort. For example, to our knowledge, ours is the first to show that this variant is also present in considerable frequencies in individuals self-identifying as Pacific Islander (Figure 1). Although it has been proposed that this variant does not contribute to negative health outcomes, our study is 1 of the first to systematically analyze its association with hundreds of diseases across multiple diverse cohorts.9-15 The results of our PheWAS indicate that this variant is likely not associated with increased incidence of common disease, based on the 1400 phecodes available for testing in AoU as well as the meta-analysis with BioVU and MVP (Figure 4). The low ANC associated with the Duffy-null genotype reflects the absolute number of circulating neutrophils, which only account for 4.5% of mature marrow neutrophils and 1.7% of total marrow granulocytes.8,43 Individuals with African ancestry, the majority of whom are Duffy-null, have comparable stem cell number and myeloid maturation with individuals with European ancestry but have a minor reduction in hematopoietic myeloid progenitors at steady-state and diminished neutrophil release.8,56-59 Despite these steady-state differences, individuals with African ancestry may mobilize peripheral blood stem cells better than those with European ancestry.8,60 Therefore, ANC likely does not properly reflect the ability of the bone marrow to produce functioning cells when needed, and minor reductions in these counts need not result in an increased risk of infection.8,10-12 Furthermore, although Duffy expression is absent on red blood cells in Duffy-null individuals, it is still expressed in other tissues, such as endothelial cells. As a result, it likely continues to play a role in immune system regulation by binding and scavenging inflammatory and homeostatic chemokines.25,26,61 Interestingly, our PheWAS reveals a lower risk of diseases of WBCs among Duffy-null individuals. This correlation is mirrored in our observations that Duffy-null individuals are less likely to have severe neutropenia (Figure 3) and is in line with previous suggestions that the alteration of cytokine concentrations/responses in Duffy-null individuals may lead to improved host defense, such as with malaria.62 However, this association could also be an artifact of how individuals with phecodes within the same group (ie, hematopoietic) are excluded as controls. For example, if an individual is classified as a case for “decreased WBC,” they will be excluded as a control for “diseases of WBCs.”

Although lacking clear disease associations, the link between this variant and underrecognized chronic benign neutropenia has contributed to health inequities within the United States that disproportionately affect Black patients, although impacts may also be seen in other minoritized racial and ethnic groups in the United States, given the appreciable percentage of Duffy-null individuals among the Hispanic, Middle Eastern, and Pacific Islander self-reported race and ethnicity groups within AoU (Figure 1). For instance, individuals with significant African admixture are more likely to be precluded from treatments involving cytotoxic drugs, are on average given lower doses, and their treatment is more likely to be discontinued because of undiagnosed BEN.32-36,63 Similar trends are seen for chemotherapy in which low WBC leads to delayed chemotherapy treatment and reduced dosages for African American women with breast cancer, potentially contributing to their decreased survival rates as compared with European American women, although there are, of course, many other factors that contribute to racial inequities in health and health care.37-40,42,64 Moreover, the use of WBC as clinical eligibility criteria contributes to an underrepresentation of African American individuals in clinical trials.65,66 Alternatively, Duffy-null individuals with mild infections may be overlooked for medical treatment if they still fall within the Eurocentric reference range.51 Such impacts on health care treatment because of misinterpretation of low WBC or ANC would not be reflected in our case/control PheWAS analysis of disease prevalence but would be expected to affect appropriate clinical care and potentially disease outcomes.

Despite emerging evidence of the role of Duffy-null status in appropriate interpretation of blood count values, and subsequent treatment decisions, this variant is rarely screened for in clinical care. Previous work has suggested that race be taken into consideration when interpreting blood cell counts, but our work, and that of others, demonstrate that genotyping for the Duffy-null variant is far more accurate for diagnosing benign neutropenia than using self-identified race (Figure 2).2,67 Similarly, the presence of the homozygous rs2814778-C SNP is a better predictor of the discontinuation of azathioprine attributed to hematopoietic toxicity than race.34 Moreover, Duffy-null individuals [Fy(a−b−)] can develop antibodies, such as anti-Fya or Fy3-6, if exposed to Duffy-positive blood during transfusions, pregnancy. or transplantation, potentially leading to hemolytic reactions or disease.68 Therefore, genotyping (or alternative assessment of Duffy blood group system) is crucial for accurate interpretation of clinical tests and risk assessment during blood transfusions and pregnancies, especially as populations become more admixed, increasing the number of individuals who may not self-identify as Black or African American but are Duffy-null, which may be poorly recognized by clinicians and health systems.69-71

Because of the intrinsic challenges presented by using EHR, there are some limitations to our analysis. For example, volunteer bias likely leads to an overrepresentation of healthy and socioeconomically advantaged participants.72,73 EHR data are also often incomplete, contains inconsistencies in data entry and documentation practices across sites, and phecodes are entered for insurance purposes rather than research purposes.74-77 Although we applied additional data cleaning steps and control variables, heterogeneity in data entry across institutions cannot be fully mitigated. Additionally, although we excluded individuals undergoing chemotherapy because of its effects on blood cell indices, we did not comprehensively exclude all drugs with potential idiosyncratic reactions leading to neutropenia; however, use of median values should limit the impact of such drugs on our results.78 Moreover, previous evidence points to the impact of implicit bias of gender, race, education level, and socioeconomic status on diagnostic rates, which can be hard to disentangle from differing incidence rates because of the health effects of discrimination.79-83 For these reasons, we included race in our main PheWAS model and any results that differed by race should be explored further as EHR-based cohorts grow and there is an increase in individuals from underrepresented self-reported race and ethnicity groups, such as Pacific Islander and Middle Eastern. Many of these associations that differed in our model that did not include race as a covariate were related to conditions that have previously been shown to differ by race, rather than ancestry, such as those associated with pregnancy complications, genitourinary conditions, pain, and inflammation (supplemental Table 2C-D). Lastly, our study lacked power to assess certain infectious diseases that, although prevalent globally, have low rates in the United States, including cholera, measles, Ebola, Zika, and Chikungunya, which are more common in regions with high rs2814778-CC allele frequencies.84 Future research using global biobanks with linked health records could explore these associations more comprehensively.

Although based on our results the Duffy-null variant alone does not contribute to increased incidence of common diseases, prior research indicates that the underrecognition of the variant’s effects on neutrophil counts can lead to health disparities. In the context of these findings that the genotype itself does not confer health disadvantages in US cohorts, in terms of disease prevalence, future research should be particularly directed at evaluating the effects of clinical misinterpretations of Duffy-null–associated neutrophil counts on mortality as well as on medication prescription patterns and chemotherapy treatments.39,65 Because complete blood cell counts are 1 of the most routine clinical health assessments, it is imperative that clinicians understand the role of the homozygous rs2814778-C SNP in apparent neutropenia to avoid unnecessary treatment decisions and decreased standards of care. In the short term, we advocate for the development of Duffy-null–specific neutrophil reference ranges for all populations as proposed by Merz et al.85 Moreover, we uphold their proposed language refinement in which “BEN” should be replaced with “Duffy-null–associated neutrophil count.” This adjustment is crucial because of the identification of Duffy-null individuals across diverse self-identified race and ethnicity groups within the United States and globally. Additionally, this change aims to untangle the misconception of race as a biological category and better reflects the underlying mechanistic cause of reduced neutrophil counts. Short-term solutions could involve Fy(a−b−) phenotyping to better guide clinical interpretations, whereas longer-term goals should focus on developing genotype-specific reference ranges for blood indices that account for broader genetic diversity. This could help mitigate health disparities caused by reliance on Eurocentric reference ranges and improve the accuracy of blood cell measurements for all populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants and research teams from the All of Us, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Biobank, and Million Veteran Program studies. The authors acknowledge the All of Us participants for their contributions, without whom this research would not have been possible. The authors also thank the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us research program for making available the participant data examined in this study.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health for the project “Polygenic Risk Methods in Diverse Populations (PRIMED) Consortium,” with grant funding for EndoPhenotype InCorporated PRS (National Human Genome Research Institute grant U01HG011720) study site.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: M.R.H. and L.M.R. conceived and designed the study; M.R.H., M.M.S., J.E.H., and P.A. conducted and/or contributed to the data analyses; M.M.S., J.E.H., P.A., A.R., and L.M.R. supervised the study; M.R.H. and L.M.R. drafted the manuscript; and all authors interpreted the results, and reviewed, revised, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Laura M. Raffield, Department of Genetics, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 5042 Genetic Medicine Building, 120 Mason Farm Rd, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; email: laura_raffield@unc.edu.

References

Author notes

Full Million Veteran Program phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) summary statistics are available on the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (study accession phs002453; direct FTP link: https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbgap/studies/phs002453/analyses/).

Full summary statistics are available with the manuscript. All of Us PheWAS Workspace can be available on request from the corresponding author, Laura M. Raffield (raffield@email.unc.edu); and All of Us data are publicly available to all approved researchers.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.