Key Points

Patients with LCH in childhood report suboptimal quality of life and high frequency of fatigue, depression, pain and attention deficits.

Patients with single-system disease and those with multisystem disease with the longest treatment duration reported the best quality of life.

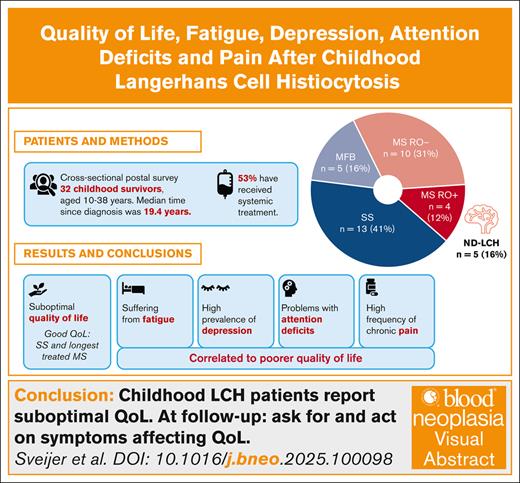

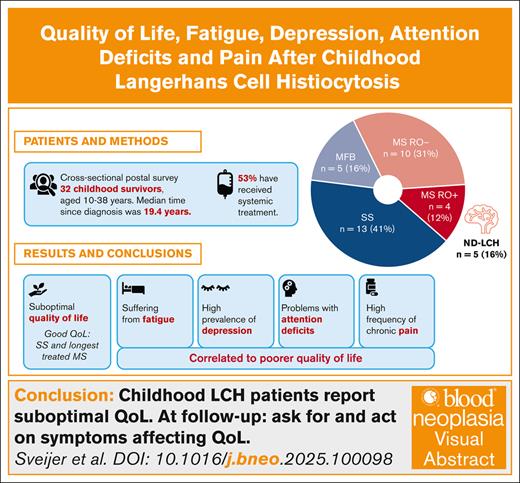

Visual Abstract

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is an inflammatory myeloid neoplasia with variable clinical presentation, ranging from self-healing single lesions to multisystem, potentially fatal disease. Long-term consequences, including progressive central nervous system (CNS) neurodegeneration, are common. In this cross-sectional postal survey, we investigated how LCH affects long-term everyday life. All individuals aged ≥10 years diagnosed with LCH in childhood ≥5 years ago in Stockholm from 1990 to 2014 were invited to participate. Thirty-two of 61 eligible individuals (52%) answered questionnaires assessing health-related quality of life (HRQOL), fatigue, pain, depression, and attention deficits. Their median postdiagnosis time was 19.4 years. Overall, 14 of 32 (44%) had had multisystem disease, including 4 (12%) with risk organ involvement, and 17 of 32 (53%) had received systemic treatment. Five (16%) had CNS involvement, all with neurodegeneration. The mean total HRQOL score was 78.8 and the mean total fatigue score 68.7 (Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory). Five (16%) reported a diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorder. In patients aged ≥15 years, 42% reported long-lasting pain, and 27% had scores indicating depression. Poorer HRQOL correlated with fatigue and symptoms of depression and attention deficits. Patients with single-system disease and patients with multisystem disease with the longest duration of systemic treatment reported the best HRQOL. We conclude that patients with childhood LCH report high frequencies of fatigue, long-lasting pain, and symptoms of depression and attention deficit in the long term, which are associated with poorer quality of life and should be evaluated at follow-up. We also raise the question of whether longer treatment may reduce long-term consequences and have a positive impact on perceived quality of life.

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is an inflammatory myeloid neoplasia with a wide range of clinical manifestations.1 Survival has improved markedly, but still approximately half of the patients report at least 1 long-term consequence. Among patients with multisystem (MS) disease, sequelae are even more frequent.1-5 Neuroendocrine complications, such as diabetes insipidus, are the most common late-effects, and other neurological consequences are reported in ∼10% of the patients.1-6 Notably, up to 20% of all children diagnosed with LCH have been reported to develop neuroradiological findings in the central nervous system (CNS) of LCH-associated neurodegeneration (ND-LCH).6-8 This is a slowly progressive complication that may develop years after assumed remission.1,4,6 ND-LCH is diagnosed by characteristic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in the cerebellar dentate nuclei, pons, and/or basal ganglia.6,7,9 Clinically, ND-LCH is associated with neurological dysfunction, often cerebellar symptoms and spasticity, and cognitive dysfunction, such as problems with attention, processing speed, and verbal and visuospatial working memory.2,6,8,10-13

Due to the wide clinical variability of LCH, from self-healing single lesions to potentially fatal MS disease with risk organ involvement (RO+), the treatment differs from “wait-and-watch” or local treatment with steroids or curettage to chemotherapy and nowadays also targeted therapies.1,14 Treatment-related sequelae have been reported to affect up to 75% of all survivors of childhood cancer.15-17 In long-term follow-up studies of childhood cancer survivors, a high burden of morbidity with negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is described.17,18 Moreover, neurological and cognitive complications after childhood cancer are reported to have severe impact on daily life.15,18

Because CNS complications are particularly common in LCH and the development of ND-LCH is often slow, long-term evaluations are of special interest in LCH. However, there are few and inconsistent long-term follow-up studies on HRQOL in LCH. One study on skeletal LCH found no reduction of HRQOL, whereas other studies on MS-LCH and all forms of LCH found reduced HRQOL.2,19-22 Our study aimed to investigate how childhood LCH affects long-term HRQOL and its associations with fatigue, pain, attention deficits, and depression, with the aim to better understand how to reduce late consequences and improve the quality of life of LCH survivors.

Methods

Patients

Patients aged <18 years treated for LCH at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, from 1990 to 2014 were identified through the hospital’s disease registry. Eligible to participate were individuals aged ≥10 years who had been diagnosed with LCH ≥5 years ago. Study information and consent forms were sent by postal mail, followed by 1 to 2 reminders, together with questionnaires to be answered by consenting patients and parents of minors. Clinical data were extracted from the patients’ medical files.

Questionnaires

We designed a complementary study-specific self- and parent-report questionnaire to assess educational level, employment status, marital status, symptoms of depression, fatigue, neurodevelopmental disorders (such as attention deficits, autism, and Asperger syndrome), pain, and quality of life, including questions about suspected and current diagnoses. All questions and scales are presented in the supplemental Methods.

For pain assessment, patients rated pain experienced over the past year on a traditional 10-cm visual analogue scale, ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain). For assessment of quality of life, psychosocial health, and physical health, patients rated their experience over the past year on a 10-point scale, from 0 (worst possible) to 10 (best possible). Only parent-reports were collected from patients aged 10 to 14 years, both self- and parent-reports were collected from patients aged 15 to 17 years, and only self-reports were collected for adults.

HRQOL and fatigue were also assessed using validated questionnaires from Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL).23,24 The PedsQL Generic Core Scale 4.0 (hereafter referred to as PedsQL) for HRQOL covers 23 items, giving a total HRQOL score that is subdivided into a physical health summary score and a psychosocial health summary score. The PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale covers 18 items, giving a total fatigue score that is subdivided into general fatigue, sleep/rest fatigue, and cognitive fatigue. The items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale and then transformed by the interpreter to a 0 to 100 scale, in which higher scores indicate better HRQOL and less fatigue, respectively. Questionnaires for self- and parent-report for the ages 8 to 12 years, 13 to 17 years, and adults (≥18 years) were used.

Depression was assessed in patients aged ≥15 years by the validated self-rated Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS-s), which covers the symptoms of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disroders, fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria for depression in 9 questions, scored on a 7-point Likert scale.25 The maximum score is 54 points, and the cutoff points are as follows: 0 to 12, no depression; 13 to 19, mild depression; 20 to 34, moderate depression; and ≥35, severe depression.

For adults, symptoms of attention deficit and hyperactivity (ADHD) were assessed with the validated Adult ADHD Self-Report Scales v1.1 (ASRS), which covers 18 items consistent with the DSM-5 criteria for ADHD, scored on a 5-point Likert scale.26 Nine items cover inattention, and 9 cover hyperactivity/impulsivity. If the sum score for 1 of the 2 scales is ≥17, ADHD is likely, and if ≥24, ADHD is very likely.27 Children (<18 years) and their parents were asked to report symptoms of ADHD using the validated Conners-3 short form covering 6 items on hyperactivity and 7 on inattention, consistent with DSM-5, on a 4-point Likert scale and then transformed with a scoring grid by the interpreter. The interpretation says what is typical or atypical for the patients’ age and gender.28

Nonresponse analysis

In accordance with the ethical permit, data were extracted from the medical files of all patients identified. Selected parameters were compared between the participating patients who responded to the questionnaires (responders) and those who did not participate (nonresponders).

Statistical methods

Statistical Package and Service Solutions software, version 28.0.1.0 (142), was used for analysis. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the cohort. Data from surveys were considered not normally distributed, and nonparametric statistics, Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test, were used. For group differences, no further adjustments were made due to small group sizes. The Pearson correlation coefficient (PC) was used to assess associations between variables for both overall and subscale scores. For nonresponse analysis, Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney U test was used for numerical variables. Reported scores from ASRS and Conners-3 questionnaires were transformed to a z score, which compares each individual to the mean of the cohort, to be able to compare all patients' scores (symptoms) irrespective of the questionnaire used. Parent reports were analyzed separately and then compared with corresponding child’s self-report by correlation analyses.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Sweden (2020-03940 and 2023-02219-02), and written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled study patients (ie, responders) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Study cohort

Sixty-five patients were identified in the diagnostic registry, of whom 61 were offered to participate in the study. Two patients treated outside of Stockholm County, and 2 with a diagnosis other than LCH were excluded. Thirty-two patients (52%) responded (56% female), of whom 2 had missing data on fatigue.

The patients’ median age at the time of the study was 22.5 years (range, 10-38): 6 of 32 (19%) were aged 10 to 14 years; 3 of 32 (9%) were aged 15 to 17 years; and 23 of 32 (72%) were adults (≥18 years). The median age at LCH diagnosis was 3.1 years (range, 0.2-16.3). Patients with RO+ (n = 4) were the youngest at diagnosis (median, 0.5 years; range, 0.2-1.3). The median time from diagnosis to the time of the study was 19.4 years (range, 7.5-30.8).

At maximum extent of disease, 18 of 32 (56%) had single-system (SS) disease, of whom 5 had multifocal bone involvement (MFB), and 14 of 32 (44%) had MS disease, of whom 4 (12%) had RO+, including liver, spleen, and/or hematopoietic system, and 10 (31%) without risk organ involvement (RO-).4 Altogether, 27 of 32 (84%) had bone lesions, including 13 of 32 (31%) with CNS-risk lesions as defined in the LCH-III/LCH-IV international collaborative treatment protocols for children and adolescents with LCH. CNS was involved in 5 of 32 (16%). Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Of the adult patients (≥18 years), 4 of 23 (17%) reported they had received help to answer the questionnaires, 5 of 23 (22%) were living with their parents, and 20 of 23 (87%) either studied or were employed. Altogether, 8 of 32 patients (25%) in the cohort reported they had had adapted schooling. Demographics are detailed in Table 2.

Responder vs nonresponder characteristics

Responders have had more extensive disease (MS-LCH, 14 vs 3 [P = .004]; SS-LCH, 18 vs 26 [P = .004]), systemic treatment (17 vs 5; P = .007), and CNS-risk lesions (13 vs 3; P = .009) than nonresponders. Of 7 with known radiological neurodegeneration, 5 responded. There were no significant gender or age differences between responders and nonresponders. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

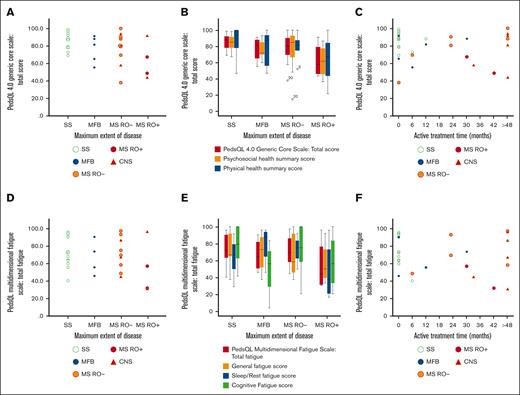

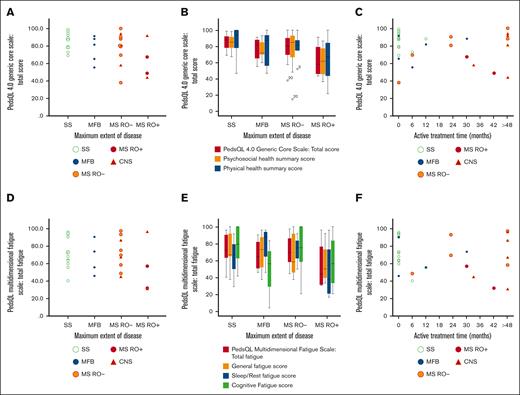

Quality of life

On a 10-graded scale, 8 of 26 patients (31%) aged ≥15 years rated their quality of life as intermediate to very bad. In PedsQL, the self-reported mean total HRQOL score of the cohort was 78.8 (standard deviation [SD], 16.2). Patients with MS-LCH RO+ had the lowest scores, with a total HRQOL of 62.7 (SD, 21.6). The scores are illustrated in Figure 1 and Tables 3 and 4, and they are detailed together with analyses of physical and psychosocial health in supplemental Table 1. Our simple study-specific self-reported 10-graded scale for quality of life correlated with the validated PedsQL score (PC, R2 = 0.42; P < .001). Similarly, our study-specific 10-graded scales for physical and psychosocial health correlated with the validated PedsQL physical and psychosocial health summary scores (PC, R2 = 0.45 [P < .001] and 0.37 [P < .001], respectively; supplemental Figure 3); scales (questions 19-21) and the corresponding ratings are presented in the supplemental Methods.

Quality of life and fatigue in association with maximum extent of disease and treatment duration. HRQOL was assessed with PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scale, and fatigue was assessed with PedsQL multidimensional fatigue scale. Individual responses (scores) of total HRQOL (N = 32) are illustrated by maximum extent of disease (A), with HRQOL subscales (B), and by active treatment time (C). Individual responses (scores) of total fatigue (N = 30; 2 missing) are illustrated by maximum extent of disease (D), with fatigue subscales (E), and by active treatment time (F). CNS, LCH with CNS involvement; MFB, multifocal bone; MS, multisystem; RO+, with risk organ (liver, spleen, and/or hematopoietic system) involvement; RO-, without risk organ involvement; SS, single system.

Quality of life and fatigue in association with maximum extent of disease and treatment duration. HRQOL was assessed with PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scale, and fatigue was assessed with PedsQL multidimensional fatigue scale. Individual responses (scores) of total HRQOL (N = 32) are illustrated by maximum extent of disease (A), with HRQOL subscales (B), and by active treatment time (C). Individual responses (scores) of total fatigue (N = 30; 2 missing) are illustrated by maximum extent of disease (D), with fatigue subscales (E), and by active treatment time (F). CNS, LCH with CNS involvement; MFB, multifocal bone; MS, multisystem; RO+, with risk organ (liver, spleen, and/or hematopoietic system) involvement; RO-, without risk organ involvement; SS, single system.

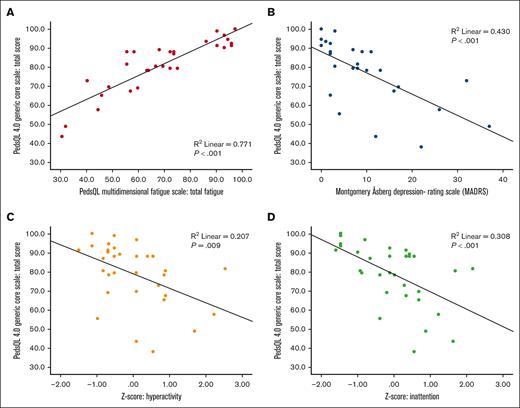

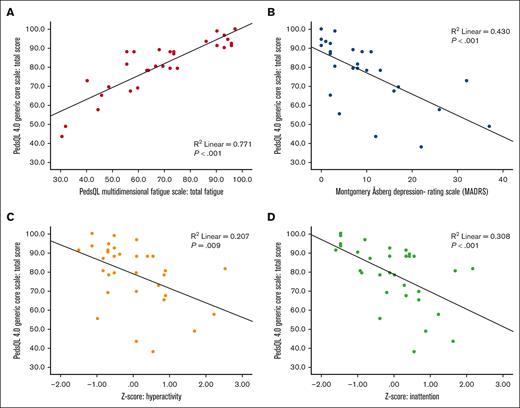

Poorer HRQOL correlated with more fatigue (PC, R2 = 0.77; P < .001), more symptoms of depression (PC, R2 = 0.43; P < .001) and attention deficits (hyperactivity PC, R2 = 0.21 [P = .009]; inattention PC, R2 = 0.31 [P < .001]; Figure 2).

Correlations between quality of life and fatigue, depression, and attention deficits. Poorer quality of life was correlated (Pearson correlation) to more fatigue (A), in which lower scores indicate worse quality of life and more fatigue; more depressive symptoms (B); and more symptoms of attention deficits, evaluated as hyperactivity (C) and inattention (D).

Correlations between quality of life and fatigue, depression, and attention deficits. Poorer quality of life was correlated (Pearson correlation) to more fatigue (A), in which lower scores indicate worse quality of life and more fatigue; more depressive symptoms (B); and more symptoms of attention deficits, evaluated as hyperactivity (C) and inattention (D).

Fatigue

Of patients aged ≥15 years, 12 of 26 (46%) responded “yes” to the question of whether they suspected to have suffered from fatigue syndrome during the last 5 years. These patients scored significantly worse on fatigue, quality of life, symptoms of depression, and ADHD than those who did not suspect fatigue syndrome (supplemental Tables 1-5).

On the PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, the self-reported mean total fatigue score of the cohort was 68.7 (SD, 19.8). RO+ patients reported most problem with fatigue (mean total fatigue score, 53.8; SD, 30.5), and those who had received systemic treatment for LCH reported markedly more fatigue (mean total fatigue score, 62.8; SD, 21.8) than those with no or local treatment (mean, 75.6; SD, 15.8; P = .092). Long duration of systemic treatment did not correlate with more fatigue (patients with systemic treatment, PC, R2 = 0.049; P = .409). Scores are illustrated in Figure 1, Tables 3 and 4, and in supplemental Table 2, together with analyses of subscores.

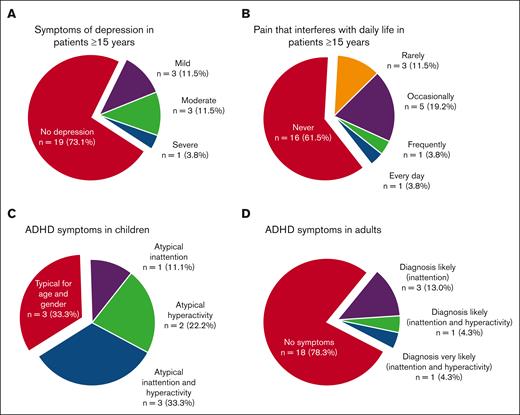

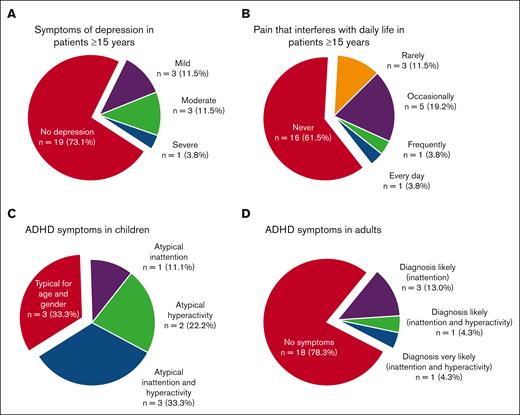

Depression

Of patients aged ≥15 years, 13 of 26 (50%) responded “yes” to the question of whether they had suspected to have suffered from depression in the last 5 years, and these patients scored significantly higher on MADRS-s (mean, 15.1 vs 4.5; P = .002) and had significantly poorer HRQOL score (mean, 68.4 vs 86.9; P = .005) than those who did not suspect to have suffered from depression. Moreover, 5 of 26 (19%) reported they had been diagnosed with and treated for depression in the last 5 years. The MADRS-s scores of all the patients aged ≥15 years indicated depression in 27% (Figure 3; Tables 3 and 4; supplemental Table 3). No parent of a child aged <15 years had suspected that their child had suffered from depression.

Frequency of symptoms of depression, pain, and attention deficits. (A-B) In patients aged ≥15 years, 27% have scores in MADRS that are indicative of depression (A), and 27% report pain that interferes with daily activities (B). (C-D) Symptoms of attention deficits not typical for age and gender were reported in Conners-3 in 67% of the children (C) and in adult ADHD Self-Report Scales v1.1 in 22% of the adults (D).

Frequency of symptoms of depression, pain, and attention deficits. (A-B) In patients aged ≥15 years, 27% have scores in MADRS that are indicative of depression (A), and 27% report pain that interferes with daily activities (B). (C-D) Symptoms of attention deficits not typical for age and gender were reported in Conners-3 in 67% of the children (C) and in adult ADHD Self-Report Scales v1.1 in 22% of the adults (D).

Symptoms of ADHD

A neurodevelopmental diagnosis was self-reported from 5 of 32 patients (16%), and all 4 patients aged ≥15 years reported that they had been prescribed medication. Of all patients aged ≥15 years, 8 of 26 (31%) stated that they had within the last 5 years suspected themselves to have a neurodevelopmental disorder. They reported significantly more depressive symptoms, poorer HRQOL, more fatigue, and more symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity than those who had not suspected a neurodevelopmental disorder (supplementary Tables 1-5). Of the patients aged ≥15 years, 5 of 23 (22%) had scores on ASRS indicating that ADHD was likely, and among children, 6 of 9 (67%) had scores on Conners-3 indicating more problems of inattention or hyperactivity than expected for their age and gender (Figure 3).

Pain

Of patients aged ≥15 years, 11 of 26 (42%) self-reported long-lasting pain when asked whether they had had pain for >3 months in the past 5 years. All of them (11/11) had seen a doctor for their pain. Eight of 10 patients (80%) with long-lasting pain had received systemic treatment for their LCH (Fisher exact test, P = .099; 1 patient with treatment for rheumatoid arthritis was excluded), and they all scored significantly poorer for quality of life, general fatigue, and symptoms of depression (supplemental Tables 1-5). The median score of pain intensity experienced in the past year in patients aged ≥15 years was 5.0 (range, 0.0-8.0) on a 10-grade scale.

For 7 of 26 patients aged ≥15 years (27%), it was reported that pain interfered with daily activities (Figure 3). One parent of a child aged <15 years reported intermittent but not long-lasting pain in the past year that almost never interfered with daily activities, whereas the rest (5/6) reported no pain.

CNS involvement

Brain MRI imaging was available in 21 patients (66%). Fourteen patients had normal MRI, whereas 5 had LCH-related neurodegenerative findings and, furthermore, cognitive difficulties on neuropsychological evaluation, of whom 2 also had neurological motor symptoms. Four of these 5 patients had diabetes insipidus, of whom 2 also had panhypopituitarism. Abnormal MRI findings, unrelated to LCH, were found in 2 patients. There were 3 patients with cognitive difficulties suspicious of clinical ND-LCH but with normal brain MRI; of these, 1 had normal neurofilament light protein in the cerebrospinal fluid, and 2 were never sampled. Only patients with MRI findings typical of LCH-related CNS involvement are included in the CNS subgroup of the study cohort when analyzing results. No significant differences in reported HRQOL, fatigue, depression, attention deficits, or pain were observed for patients with CNS involvement and neurodegeneration compared with the rest of the study cohort (Table,4). Equally, no significant differences were observed for patients with CNS-risk lesions (supplemental Tables 1-5).

Treatment time

The median time since last treatment was 11.7 years (interquartile range [IQR], 17.1-7.9). Approximately half of the patients (17/32 [53%]) had received systemic treatment, 5 of 32 (16%) local treatment, and 10 of 32 (31%) no treatment for LCH (Table 1). Duration of active systemic treatment ranged from 6 to 208 months (median, 30.0 months; IQR, 63.5-12.0). Oral maintenance treatment with mercaptopurine and methotrexate was given to 13 of 17 patients, and 1 patient had maintenance treatment with betamethasone; 6 of 14 had oral maintenance therapy for >24 months (range, 0-192; median, 18.0; IQR, 35.0-6.0). One patient with MS-LCH (skin and bone) received only local treatment of LCH and 17 years after the diagnosis of LCH started several years of oral low-dose methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis; this patient was excluded from treatment subgroup analyses. Patients with MS-LCH at maximum extent of disease who had received systemic treatment for >48 months (n = 6) reported a mean total HRQOL of 82.8, whereas patients with MS-LCH with treatment ≤48 months (n = 7) reported a mean total HRQOL of 64.6 (P = .101). The psychosocial health summary score was significantly higher in patients with MS-LCH with >48 months of treatment (86.1 vs 56.9; P = .022). They also reported significantly fewer symptoms of depression and hyperactivity, and a trend of fewer symptoms of inattention; there was no significant difference in fatigue (Figure 1; Table,4; supplemental Tables 1-5). Details of treatments are found in supplemental Table 6 and supplemental Figure 1.

Parent-child and adult-child comparisons

There are 19 of 32 parent reports: for all 9 patients aged <18 years; and 10 of 23 on HRQOL and 8 of 21 on fatigue for patients aged ≥18 years. For groups in which both parent and child reports were collected, we analyzed and report the self-reports of the children. In addition, parent scores are presented in supplemental Table 7 and parent-child comparisons in supplemental Figure 2.

The parent ratings often correlated well with their corresponding child’s self-reports: Pearson correlation for PedsQL total score was R2 of 0.917 (P < .001); total fatigue score was R2 of 0.837 (P < .001); and Conners hyperactivity score was R2 of 0.69 (P = .006). The Conners inattention score did not correlate well for patient’s self-reported score and corresponding parent-reported score (PC, R2 = 0.154; P = .296).

Overall, there were no significant differences between children (<18 years) and adults (≥18 years) for the validated questionnaires (supplemental Tables 1-5).

Discussion

Our study shows that, at follow-up, patients with LCH in childhood report a remarkably high frequency of fatigue, long-lasting pain, and symptoms of depression and attention deficit. Moreover, these symptoms were associated with poorer quality of life. Surprisingly, patients with MS-LCH with the longest duration of treatment reported unexpectedly good quality of life.

Our results, showing a suboptimal mean total HRQOL score of 78.8, 85.6, 76.3, 77.7, and 62.7 for all patients and those with SS-LCH, MFB-LCH, MS-LCH RO-, and MS-LCH RO+, respectively, are in line with previous studies on HRQOL in childhood LCH. Although PedsQL used ≥5 years after LCH diagnosis in 27 children with skeletal involvement (21 SS-LCH and 6 MS-LCH; ie, mainly milder forms of LCH) revealed a normal mean total HRQOL score of 86.2 (SD, 10.4), long-term studies on only or mainly pediatric MS-LCH, that is, more severe forms of LCH, have demonstrated reduced HRQOL, and a parent-proxy report of 28 children with LCH also reported a reduced overall PedsQL (total HRQOL score of 77.6 ± 5.15).19,20,22,29 Interestingly, our simple, self-reported, 10-graded, easy-to-use scales for quality-of-life, physical health, and psychosocial health (supplemental Methods, questions 19-21) correlated with the corresponding validated PedsQL scores.

To put these results into a broader context, a population-based study on quality of life in 486 healthy Swedish school children aged 7 to 15 years showed a PedsQL mean total HRQOL score of 82.1 (SD, 12.9), with subscores of physical and psychosocial health of 84.85 (SD, 13.5) and 80.6 (SD, 14.3), respectively.30 A Swedish study on children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis reported a mean total HRQOL score of 75.1 (SD, 16.3), and it defined suboptimal HRQOL as a PedsQL mean total score <78.6, whereas Swedish children and adolescents with diabetes mellitus type 1 report a mean total HRQOL score of 82.8 (SD, 12.4).31,32 International studies have reported a mean total HRQOL score among childhood cancer survivors (N = 389) of 71.9 (SD, 16.14) and in healthy controls (N = 5480) of 83.8 (SD, 12.65).33 Long-term mean total HRQOL scores in patients with LCH varied in our study cohort. Although our patients with SS-LCH reported normal HRQOL, patients with MFB-LCH and MS-LCH RO- reported HRQOL below normal, and patients with MS-LCH RO+ reported HRQOL even below the mean for childhood cancer survivors.

Notably, most of the patients with MS-LCH with the longest duration of treatment (>48 months), mainly because of prolonged maintenance therapy, reported a mean total HRQOL in level with the normal population (82.8), as well as fewer symptoms of depression and attention deficits. Childhood cancer survivors have previously reported “not taking life for granted” and positive posttraumatic growth in the long term.34,35 For LCH, an important but as yet unanswered question is whether, and if so to which extent, extensive treatment aiming at eradicating mutated LCH clones can reduce the extent of long-term consequences, including neurodegeneration, as well as a poorer HRQOL. Interestingly, the most critically ill patient in our study, a child with MS-LCH RO+ who developed hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis–associated LCH and was treated with intensive salvage chemotherapy, has only mild signs and symptoms of ND and actually reported a very good long-term quality of life. The abovementioned findings raise the question of whether active early therapeutic interventions, such as intensive chemotherapy and/or targeted treatments, and longer treatment duration may reduce long-term consequences; a topic which deserves further studies.36

Importantly, many of our patients reported suffering from fatigue. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that examines fatigue in patients with LCH, although it is a known problem in LCH and reported in the histiocytic disorder Erdheim-Chester disease.37-39 It is striking that our MS-LCH RO+ patients reported a similar level of fatigue as patients treated for brain tumors (total mean fatigue scores of 53.8 and 55.5 [SD 20.8], respectively) examined with the same questionnaire as in our study.40 Moreover, the mean fatigue score of our whole LCH cohort (68.7) is about the same as that of survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (mean, 68.6; SD, 16.5).40 Consistent with previous studies, we showed a strong correlation between fatigue and poorer HRQOL (Figure 2).23,41 Fatigue is a troublesome problem among childhood cancer survivors, but there are validated programs for fatigue management, especially physical activity, that may significantly reduce fatigue and could be offered to affected patients.42-44

The prevalence of depression in Sweden is reported to be 5% to 9%.45,46 In our study, 19% had been treated for depression. A high prevalence of symptoms of depression in patients with LCH has been reported previously.2,19,37,47 It is also alarming that 27% of our patients aged ≥15 years had scores on MADRS-s indicating depression (Figure 3). Individuals who suspected they have had a depression also had poorer HRQOL, which highlights the importance of asking for and acting on the symptoms of depression at follow-up.

We asked some complementary questions in addition to the validated instruments. Some results from this questionnaire were remarkable, such as the prevalence of self-reported long-lasting pain (42%) and pain that interfered with daily activities (27%). Pain is also described as a common symptom among adult patients with LCH.48 We could not find a correlation between the patient’s past LCH lesions and the location of the pain reported, raising a question on the origin of the pain. We encourage future studies examining pain in patients with LCH with validated instruments.

Behavioral problems have previously been described as a common problem in LCH, which our study confirms.47 The prevalence of ADHD in Stockholm, Sweden, is reported to be 7.7% among individuals aged 13 to 17 years and 5.6% among young adults (18-24 years).49 The reported prevalence in LCH survivors in our study is much higher, with altogether 16% having a diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorder, and 31% of patients aged ≥15 years reported that they suspected having a neurodevelopmental disorder. Positively, most of our patients reported having an independent life with employment and a family of their own. Similar to previous studies, we also observed a high frequency of adapted schooling in individuals with LCH.19,20

Notably, we found patients with suspected symptoms of ND-LCH but without MRI abnormalities, which stresses the need for more sensitive tools to detect possible early neurodegeneration. In line with this, we have recently suggested neurofilament light protein as a potential biomarker for early detection of ND-LCH.50

This study has limitations. It is a small study with a moderate response rate of 52%, which may bias the response and stability of the identified effects; such as, that participants with the longest duration of treatment had quality-of-life scores similar to those of healthy populations and that poorer quality of life was correlated to more symptoms of depression and attention deficits. Comparisons of adults vs children (<18 years, n = 9) should be interpreted with caution due to small numbers. Moreover, findings that outcomes specific to symptom burden were related to poor quality of life need to consider overlap among the measures; that is, that the multidimensional quality-of-life measure covers some of the constructs being used to predict it. A non-response analysis showed that the responders had more extensive disease and complications, which may also skew the results. Questionnaire-based studies such as this have an inherent risk of survey errors, including coverage and the patient’s interpretation of the questionnaires, and follow-up questions are not possible. This is a small cohort with heterogeneity, which complicates generalization of the result. However, the overall data still show that long-term consequences are prominent in patients with childhood LCH. More and larger studies are needed to control for confounding factors and to validate our results.

We conclude that the low HRQOL reported and the reported high frequency of pain, depression, and fatigue are noticeable and are a concern. However, we found that quality of life was correlated with symptoms that are treatable. Moreover, some patients reported an excellent HRQOL despite severe disease and heavy chemotherapy, giving rise to hope for better future HRQOL. For the future, we suggest increased awareness of HRQOL issues, asking for and acting on long-term effects of childhood LCH, and studies to investigate the possible impact of improved follow-up programs on long-term effects and everyday life, as well as studies on correlations between therapies administered and HRQOL.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Fund (KP2021-0006 [J.-I.H.] and KF2023-007 [T.v.B.G.]), the Swedish Cancer Society (23 3162 Pj [J.-I.H.]), Region Sörmland (DLL993887 [M.S.]), and Region Stockholm (ALF-grant; FoUI-960717 [J.-I.H.]).

Authorship

Contribution: M.S. reviewed all questionnaires, performed data entry and compiled data, did the statistical analyses, interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript, including tables and figures; D.G. helped plan the study, assisted in distributing questionnaires, interpreted data, and assisted in drafting the manuscript; H.H. distributed questionnaires and performed data entry, compiled data, and analyzed data on the quality of life part; E.Z. provided expertise on neuropsychiatric disorders and their evaluation; J.-I.H. conceived and planned the study, interpreted data, assisted in drafting the manuscript, and finalized the manuscript together with T.v.B.G; T.v.B.G. conceived and planned the study, interpreted data, assisted in drafting the manuscript, and finalized the manuscript together with J.-I.H; M.S., D.G., and T.v.B.G. verified the underlying data; and all authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, had access to all data in the study, and accept the responsibility to submit for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tatiana von Bahr Greenwood, Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Karolinska Institutet, Tomtebodavägen 18A, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden; email: tatiana.greenwood@ki.se; and Jan-Inge Henter, Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Karolinska Institutet, Tomtebodavägen 18A, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden; email: jan-inge.henter@ki.se.

References

Author notes

Data cannot be shared as this was not included in the ethical application. For further information, contact the corresponding authors, Tatiana von Bahr Greenwood (tatiana.greenwood@ki.se) or Jan-Inge Henter (jan-inge.henter@ki.se).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.