Key Points

The IWG MDS Molecular Taxonomy can be applied in real-world hematopathology practice, and molecular classes are largely stable over time.

In a cohort receiving modern therapies, several MDS molecular classes had distinct clinicopathologic features and outcomes.

Visual Abstract

Hematopathology classification increasingly relies on genetics, but most myelodysplastic syndromes/neoplasms (MDS) remain classified based on morphologic criteria such as blasts and dysplasia. Recently, the MDS International Working Group (IWG) developed an MDS molecular taxonomy using a large international cohort. Here, we applied this taxonomy to a single-institution cohort of 392 patients with MDS and oligomonocytic chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (oCMML) receiving modern standard of care. Cases were also classified per International Consensus Classification (ICC) and World Health Organization (WHO) 5th edition (WHO5). All patients were assigned to a molecular class; TP53-complex karyotype (TP53-CK; 29%), IDH-STAG2 (14%), SF3B1 (9%), and No-event (6%) were the most frequent. Clinical presentation varied across classes, with oCMML being most frequent in biallelic-TET2 (bi-TET2) (42%), EZH2-ASXL1 (50%), and clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance (CCUS)-like classes (33%). Molecular classifications were stable; only 18% changed upon follow-up. Molecular classes showed significant differences in overall survival (OS). On multivariable analyses (MVAs) that included stem cell transplant, longer OS was seen with SF3B1, del5q, and bi-TET2; shorter OS was seen with TP53-CK and −7/SETBP1. In MVAs for WHO5 and ICC entities, oCMML2 was the only morphologically defined entity that affected OS. For predicting OS, IWG molecular classification had a Harrell's C-index of 0.75, compared with WHO5 and ICC Harrell's C-indices of 0.74 and 0.73, respectively. Altogether, these results show that the IWG molecular taxonomy can be applied in routine practice, with several classes exhibiting distinct clinical features and outcomes.

Introduction

The classification of myelodysplastic syndromes/neoplasms (MDS) has been recently updated in 2 schemes, the World Health Organization (WHO) 5th edition (WHO5) and the International Consensus Classification (ICC), which were finalized in 2024 and 2025, respectively.1,2 Both systems introduced 2 genetically defined subtypes: (1) MDS with mutated SF3B1/MDS with low blasts and SF3B1 mutation and (2) MDS with mutated TP53/MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation, with each of these linking genetically driven disease biology to patient clinical trajectories. However, most MDS cases remain classified based on morphologic features.3

Recent unsupervised clustering approaches have enabled recognition of MDS genetic subgroups that could inform classification and help predict clinical outcomes.4-7 A molecular MDS classification offers several potential advantages: (1) improved reproducibility compared with assessing morphology8,9; (2) improved genetics-based prediction of disease progression, enabling more precise disease monitoring; and (3) identification of therapeutic targets and optimization of clinical trial design and drug development.10 However, a purely genetic MDS scheme also has potential limitations: (1) mutation patterns are complex and those identified by clustering algorithms may not be relevant in clinical practice; (2) evidence-based treatment decisions may depend on studies that previously relied on clinical parameters (such as blood counts) and disease subgroups within previous WHO Classifications; and (3) although next-generation sequencing (NGS) is standard of care in many countries, it may not be available in all practice settings.

The most recent classification systems for MDS integrate genetic and morphologic parameters, including the blast percentage, by applying them in a defined hierarchy.11 Recent evidence has shown that some well-defined genetic MDS subgroups show a wide spectrum of blast percentages, suggesting that blast percentage could function more as a “stage” of disease rather than be disease defining (“MDS with excess/increased blasts”).4,7,12 Notably, the bone marrow (BM) blast percentage is already incorporated into the widely-used revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS)13 and the molecular IPSS (IPSS-M).14

Recently, the MDS International Working Group (IWG) developed a genetic MDS taxonomy, containing 18 molecular classes based on mutations and karyotype abnormalities.15 The molecular classes showed significant differences in clinical characteristics and outcomes. This study was based on patients from multiple institutions treated over a broad time range (1999-2016), with limited information about treatments or baseline clinical parameters, and included a significant number of patients with non-MDS myeloid neoplasms (acute myeloid leukemia [AML] and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms [MDS/MPN]). Moreover, the study was based on centrally performed genetic analyses rather than relying on clinical molecular panels, raising questions as to its applicability in routine practice. Therefore, we analyzed a series of MDS cases diagnosed and treated at a single institution, to test the feasibility of applying the IWG classification scheme, and to determine clinicopathologic features and patient outcomes for different genetic classes within our cohort. We also compared the IWG classes with ICC/WHO5 MDS entities with respect to predicting patient survival.

Methods

Data on patients diagnosed with MDS between 2016 to 2022 were collected from the Massachusetts General Hospital pathology archives. The MDS diagnosis was based on the revised 4th edition WHO classification (WHO4R) in use during the study period: cases with 0.5 × 109/L to <1.0 × 109/L blood monocytes that would be considered within chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) according to WHO5 and ICC (so-called oligomonocytic CMML [oCMML]) were included; other MDS/MPN entities were excluded. All cases had no previous MDS therapy and had adequate NGS and cytogenetics data at the time of diagnosis. The NGS panels used varied over the study period and included Heme SNaPshot and Rapid Heme Panels.16,17 Relevant aberrations used in the IWG scheme could be determined from the NGS panels, including loss of heterozygosity of the TP53 locus; of note, earlier sequencing panel versions used in 29% of the cohort cases did not assess for DDX41, MYC, and KMT2A-PTD aberrations. Only mutations with a variant allele fraction (VAF) of ≥2% were used. Clinicopathologic characteristics at diagnosis were recorded, including peripheral blood counts, BM histologic findings, and previous cytotoxic or radiation therapy.

Each patient was assigned an IWG molecular class and also classified per ICC and WHO5. Treatments administered after diagnosis (including allogeneic stem cell transplant [SCT]), progression to AML, and OS were determined based on electronic medical records. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to the time of death for any reason; patients were otherwise censored at the time they were last known to be alive as of the most recent follow-up date (21 March 2025). For patients who had follow-up genetic testing at later time points before any SCT, the IWG class was redetermined. Clinicopathologic features and patient outcomes for the various IWG classes, and outcomes for ICC and WHO5 categories, were compared.

The Fisher exact test and t test were used to compare variables, and OS was compared by Kaplan-Meier analyses. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards modeling for OS was performed that included disease category (by ICC, WHO5, or IWG) and IPSS-M together with SCT as a time-dependent variable competing with death. The Harrell C-index was used to compare modeling of OS by ICC, WHO5, and IWG categories, and IPSS-M, after considering SCT. Analyses were all 2-tailed and P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

This is a retrospective study, and only existing clinical and pathology data were used. For this type of study, informed consent is not required. This study was approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board.

Results

Clinicopathologic features of cohort and molecular classes

The descriptive characteristics of our cohort are summarized in Table 1. A total of 392 patients were analyzed. Most patients (68%) were male, and the median age of diagnosis was 72 years; 26% of patients had previous cytotoxic or radiation therapy for a nonmyeloid neoplasm. Overall, 42% of patients received a hypomethylating agent (HMA) such as azacytidine or decitabine, and an additional 8% received HMA in combination with venetoclax. Nine percent of patients received low-intensity treatments (lenalidomide, luspatercept, single-agent small molecule inhibitors, or other low-intensity therapies, except HMA), whereas 38% received supportive care such as erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (Table 1). Overall, 29% of patients underwent SCT. The median follow-up was 25.6 months for all patients (62.2 months for surviving patients), and 69% of patients had died by the last follow-up date. The distributions of WHO5 and ICC classifications (based on morphology and genetics, considering “therapy-relatedness” as an independent qualifier) were similar to those of other large MDS cohorts,5 and are summarized in Figure 1. Given that the inclusion criteria were based on WHO4R, reclassification by WHO5 and ICC resulted in 13% and 12% oCMML, 2% and 1% AML, and 1% and <1% clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance (CCUS) cases, respectively; the latter were cases with <10% dysplasia in any lineage, but with MDS-defining events according to WHO4R that were eliminated in WHO5/ICC.

Whole cohort characteristics

| . | Whole cohort (N = 392) . |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 72 (64-77) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 126 (32) |

| Male | 266 (68) |

| Type of MDS | |

| Primary | 289 (74) |

| Therapy-related | 103 (26) |

| Treatments | |

| HMA | 165 (42) |

| HMA/venetoclax | 30 (8) |

| Intensive chemotherapy | 10 (3) |

| Low-intensity treatment | 36 (9) |

| None/supportive | 147 (38) |

| Unknown | 4 (1) |

| SCT | 114 (29) |

| Transformed to AML | 103 (26) |

| Median follow-up (mo) | 26 (10-52) |

| . | Whole cohort (N = 392) . |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 72 (64-77) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 126 (32) |

| Male | 266 (68) |

| Type of MDS | |

| Primary | 289 (74) |

| Therapy-related | 103 (26) |

| Treatments | |

| HMA | 165 (42) |

| HMA/venetoclax | 30 (8) |

| Intensive chemotherapy | 10 (3) |

| Low-intensity treatment | 36 (9) |

| None/supportive | 147 (38) |

| Unknown | 4 (1) |

| SCT | 114 (29) |

| Transformed to AML | 103 (26) |

| Median follow-up (mo) | 26 (10-52) |

Data shown as median (interquartile range) or number (%). Low-intensity treatment refers to lenalidomide, luspatercept, investigational, or small-molecule inhibitor.

WHO5, ICC, and IWG classification distributions for the cohort, and clinical findings of IWG classes. After reclassification of our WHO4R-based 2016-to-2022 cohort into WHO5/ICC, most of the cohort (84%/87%) remained as MDS. Panels A and B show the WHO5 and ICC MDS subtype distributions, respectively. Cases reclassified as non-MDS entities in WHO5/ICC were 13%/12% oCMML, 2%/1% AML, and 1%/<1% CCUS, respectively. All cases in the cohort could be assigned into IWG molecular classes (panel C, n for each class given in parentheses). The molecular classes had variable clinical findings (panel D, n for each class given in parentheses). Colors are relative to the medians for all patients, which were: age, 71.6 years; WBC, 2.8 × 109/L; HGB, 9.1 g/dL; PLT, 85 × 109/L; and oCMML, 13%. Classes with <2% of the whole cohort were not subanalyzed due to low sample size: der(1;7) (n = 2), SRSF2 (n = 3), ZRSR2 (n = 3), and AML-like (n = 7, of which 6 of 7 were reclassified to AML instead of MDS by ICC and/or WHO5). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, compared with remaining patients in the cohort. HGB, hemoglobin; NOS, not otherwise specified; PLT, platelets; WBC, white blood cell count.

WHO5, ICC, and IWG classification distributions for the cohort, and clinical findings of IWG classes. After reclassification of our WHO4R-based 2016-to-2022 cohort into WHO5/ICC, most of the cohort (84%/87%) remained as MDS. Panels A and B show the WHO5 and ICC MDS subtype distributions, respectively. Cases reclassified as non-MDS entities in WHO5/ICC were 13%/12% oCMML, 2%/1% AML, and 1%/<1% CCUS, respectively. All cases in the cohort could be assigned into IWG molecular classes (panel C, n for each class given in parentheses). The molecular classes had variable clinical findings (panel D, n for each class given in parentheses). Colors are relative to the medians for all patients, which were: age, 71.6 years; WBC, 2.8 × 109/L; HGB, 9.1 g/dL; PLT, 85 × 109/L; and oCMML, 13%. Classes with <2% of the whole cohort were not subanalyzed due to low sample size: der(1;7) (n = 2), SRSF2 (n = 3), ZRSR2 (n = 3), and AML-like (n = 7, of which 6 of 7 were reclassified to AML instead of MDS by ICC and/or WHO5). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, compared with remaining patients in the cohort. HGB, hemoglobin; NOS, not otherwise specified; PLT, platelets; WBC, white blood cell count.

All patients could be assigned to a molecular class, with No-event encompassing cases with normal karyotype that lacked any known pathogenic mutations on clinical NGS panels. The most frequent classes were TP53–complex karyotype (TP53-CK; 29%), IDH-STAG2 (14%), and SF3B1 (9%; Figure 1). The AML-like, der(1;7), SRSF2, and ZRSR2 classes each had <2% of patients and were excluded from comparative univariate analyses. No-event was the fourth most frequent class (6% of patients). Most of the SF3B1 (76%/82%), del5q (75%/69%), and TP53-CK (70%/73%) cases overlapped with their corresponding respective ICC/WHO5 MDS entities. Cases classified into morphologically defined MDS entities (MDS–low blasts [LB], MDS-hypoplastic, and MDS-fibrosis in WHO5; MDS–excess blasts [EB] and MDS/AML in ICC, for example) belonged to several molecular classes, indicating genetic heterogeneity within these entities (supplemental Figure 1). There was a trend (P = .07) toward a difference in IWG class distributions between MDS–EB (5%-9% BM blasts) vs MDS/AML (≥10% BM or blood blasts): there were more frequent TP53-CK (the subset lacking a defining multihit TP53 mutation) and DDX41 and less frequent “molecularly not otherwise specified” (mNOS) in MDS/AML. Regarding WHO5 classification entities, every molecular class was represented within MDS-LB, whereas MDS-hypoplastic included IDH-STAG2, mNOS, No-event, CCUS-like, TP53-CK, and U2AF1-34 classes, and MDS-fibrosis included IDH-STAG2, mNOS, No-event, CCUS-like, −7/SETBP1, and DDX41 classes (supplemental Figure 1).

The percentage of cases in each molecular class that were either therapy-related, had increased blasts, or had ring sideroblasts (RSs), were variable, with significant differences seen among classes (supplemental Table 1). Therapy-related cases were more frequent in TP53-CK (44%, P < .001), and less frequent in IDH-STAG2 (9%, P = .002) and No-event (8%, P = .034). Increased (≥5%) blasts were seen in 44% of the whole cohort, occurred across molecular classes, and were most frequent in TP53-CK (61%, P < .001) and DDX41 (90%, P = .006). Among the 70% of all patients that had iron stain performed (n = 275), 44% had any RSs, occurring across all classes with varying frequencies. The presence of any RSs was significantly higher in SF3B1 (97%, P < .0001) and TP53-CK (64%, P = .0003), as was the presence of increased (≥15%) RSs (SF3B1: 81%; P < .0001 and TP53-CK: 39%; P = .0049), reflecting the strong association of RSs with SF3B1 and (to a lesser extent) TP53 mutations.18

Molecular classes had variable clinical characteristics (Figure 1; supplemental Table 1). Median ages ranged from 65 to 76 years, with younger age seen in No-event (median, 65 years; P = .011) and mNOS (median, 65 years; P = .0025) and with older age seen in bi-TET2 (median, 76 years; P = .013). Higher white blood cell count was seen in del5q (median, 4.3 × 109/L; P = .020) and SF3B1 (median, 4.3 × 109/L; P < .001). Platelet counts were also higher in del5q (median, 206 × 109/L; P = .001) and SF3B1 (median, 265 × 109/L; P < .001). Because CMML in both ICC and WHO5 now includes oCMML cases (0.5 × 109/L to <1 × 109/L monocytes) that were previously characterized as MDS, we explored the distribution of oCMML cases. We found significantly higher percentages of oCMML in bi-TET2 (42%, P < .001), EZH2-ASXL1 (50%, P = .005), and CCUS-like (33%, P = .011).

Clinical outcomes of molecular classes

We were interested in whether molecular classes aligned with specific treatment patterns. We found that frontline treatments did differ among molecular classes. Patients with CCUS-like (P = .01) and SF3B1 (P < .0001) were less likely to be treated with HMA or more intensive therapies, whereas those with bi-TET2 (P = .09) and del5q (P = .06) showed a trend toward being treated less often with HMA or intensive therapies. Conversely, patients with IDH2-STAG2 (P = .007) and TP53-CK (P < .0001) classes were more likely to receive HMA or intensive therapies. Patients with mNOS (P = .0074) were more likely to undergo SCT, whereas those with SF3B1 (P = .0181) were less likely to undergo SCT (supplemental Figure 2). Three patients (2 IDH-STAG2 and 1 U2AF1-157) received an IDH inhibitor (enasidenib or ivosidenib). Within IDH-STAG2, 1 patient received enasidenib at diagnosis and is still alive after 7 years, and 1 patient received ivosidenib 2.5 years after diagnosis and died 3 years later; neither patient received a SCT.

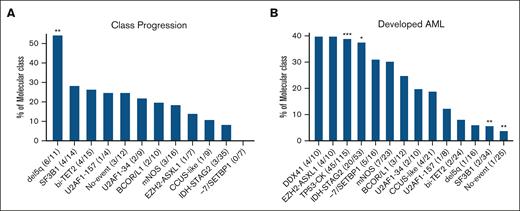

We determined the stability of the IWG classes among the 170 cases (43% of all cases) that had genetic studies performed at follow-up. Progression to a higher class in the molecular taxonomy hierarchy was seen in 30 (18%) cases, including 3 patients with oCMML (Figure 2). The genetic progressions coincided with development of increased blasts or AML in 5 of 27 and 2 of 27 patients with MDS, respectively. For the 3 patients with oCMML with class progression, the monocyte range remained within 0.5 × 109/L to <1 × 109/L, without development of overt CMML or AML. In the del5q class, 11 patients (69% of del5q) had follow-up genetic data available: 6 of 11 patients (54%) progressed, all to the TP53-CK class. Of the 6 patients with del5q with class progression, 1 patient who progressed to TP53-CK had a monoallelic TP53 mutation (VAF of 20%) at initial diagnosis. Progression to AML was also determined for each molecular class (Figure 2). Across the molecular classes, AML progression was more frequent in TP53-CK (39%, P < .001) and IDH-STAG2 (38%, P = .046), and less frequent in SF3B1 (6%, P = .004) and No-event (4%, P = .008).

Class progressions and development of AML. The proportions of each class that underwent class progression (A) or developed AML (B) are shown. For panel A, 170 patients in the whole cohort had genetic testing at a later follow-up date that allowed for assessing class progression, with only 30 of 170 patients progressing to a new class at follow-up (17.6%); the number with class progression and the number with follow-up testing are given in parentheses for each class. Of the classes we analyzed, the highest (DDX41) and second highest (TP53-CK, which could not progress to germ line–enriched DDX41) within the taxonomy hierarchy are not included. For panel B, the number that progressed to AML and the number in each class are given in parentheses (this analysis was performed on the whole cohort). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with remaining patients in the cohort.

Class progressions and development of AML. The proportions of each class that underwent class progression (A) or developed AML (B) are shown. For panel A, 170 patients in the whole cohort had genetic testing at a later follow-up date that allowed for assessing class progression, with only 30 of 170 patients progressing to a new class at follow-up (17.6%); the number with class progression and the number with follow-up testing are given in parentheses for each class. Of the classes we analyzed, the highest (DDX41) and second highest (TP53-CK, which could not progress to germ line–enriched DDX41) within the taxonomy hierarchy are not included. For panel B, the number that progressed to AML and the number in each class are given in parentheses (this analysis was performed on the whole cohort). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with remaining patients in the cohort.

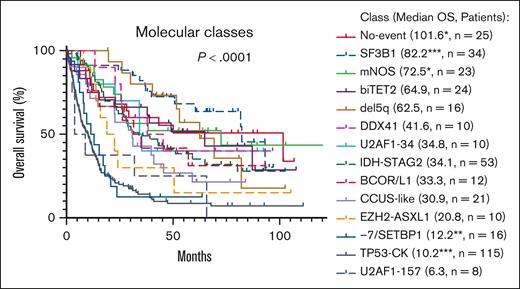

OS also varied between molecular classes (P < .0001), with median OS ranging from 6.3 months for U2AF1-157 to 101.6 months for No-event (Figure 3). By univariate analysis, the molecular classes that had significantly or borderline significantly different OS compared with other patients with MDS were del5q (hazard ratio [HR], 0.535; P = .06), SF3B1 (HR, 0.378; P = .0002), No-event (HR, 0.575; P = .048), mNOS (HR, 0.551; P = .04), U2AF1-157 (HR, 1.909; P = .085), −7/SETBP1 (HR, 2.092; P = .006), and TP53-CK (HR, 3.095; P < .0001). Increased BM blasts (≥5%) significantly affected OS for only 3 classes (Figure 4): SF3B1 (HR, 6.945; P = .0004), No-event (HR, 0.299; P = .026), and EZH2-ASXL1 (HR, 5.781; P = .01). Additional genetic abnormalities were present in the SF3B1 and EZH2-ASXL1 cases with increased blasts (supplemental Table 3). Of note, within the No-event group, 8 of 12 patients in the ≥5% BM blasts group received SCT vs 3 of 13 patients in the <5% BM blasts group.

The molecular classes showed significant differences in OS. Median OS in months is given in parentheses, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with remaining patients in the cohort. Median OS for all patients (N = 392) was 26.6 months.

The molecular classes showed significant differences in OS. Median OS in months is given in parentheses, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with remaining patients in the cohort. Median OS for all patients (N = 392) was 26.6 months.

OS of patients with <5% and ≥5% BM blasts in the molecular classes in which BM blasts significantly affected OS. The only molecular classes in which blast count significantly affected OS were SF3B1, No-event, and EZH2-ASXL1. Within the No-event class, 8 of 12 patients with ≥5% blasts received SCT compared with 3 of 13 patients in the <5% blast group.

OS of patients with <5% and ≥5% BM blasts in the molecular classes in which BM blasts significantly affected OS. The only molecular classes in which blast count significantly affected OS were SF3B1, No-event, and EZH2-ASXL1. Within the No-event class, 8 of 12 patients with ≥5% blasts received SCT compared with 3 of 13 patients in the <5% blast group.

Given the variable use of SCT among molecular classes and the strong influence of SCT on OS, multivariable analyses (MVAs) were conducted that included disease class and SCT as a time-dependent variable (Table 2). Compared with the reference group of CCUS-like (which had median OS similar to that of the entire cohort), TP53-CK (HR, 2.766; P = .0002) and −7/SETBP1 (HR, 2.465; P = .015) had significantly shorter OS, whereas SF3B1 (HR, 0.266; P = .0003), del5q (HR, 0.363; P = .015), and bi-TET2 (HR, 0.479; P = .0495) had significantly longer OS. These classes retained independent prognostic significance in a separate MVA that included marrow blasts as a covariate, with the exception of bi-TET2, which was borderline significant (HR, 0.485; P = .0531; Table 2). Conducting a similar MVA for ICC entities with MDS-MLD as the reference group, MDS-TP53 (HR, 3.353; P < .0001), MDS-SF3B1 (HR, 0.237; P < .0001), MDS-del5q (HR, 0.393; P = .02), and CMML2 (HR, 2.644; P = .018) had significantly different OS. Conducting a similar MVA for WHO5 entities with MDS-LB as the reference group, MDS–bi-TP53 (HR, 4.307; P < .0001), MDS-SF3B1 (HR, 0.283; P < .0001), and CMML2 (HR, 3.460; P = .0009) had significantly different OS, whereas MDS-del5q showed a trend toward longer OS (HR, 0.484; P = .07). The Harrell's C-indices for OS were 0.69, 0.67, and 0.66 for IWG, WHO5, and ICC, respectively, and were 0.75, 0.74, and 0.73 for IWG, WHO5, and ICC, respectively, in models that incorporated the effect of SCT. Adding marrow blasts to the IWG model that incorporated SCT slightly improved the index to 0.76. In comparison, the Harrell's C-index for the IPSS-M incorporating SCT in our cohort was 0.73.

MVA for OS

| IWG class . | IWG class incl. BM blasts . | ICC . | WHO5 . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class . | HR . | P value . | Class . | HR . | P value . | Entity . | HR . | P value . | Entity . | HR . | P value . |

| AML-like | 0.319 | .12 | AML-like | 0.277 | .09 | AML | 0.627 | .52 | AML | 0.542 | .30 |

| BCOR/L1 | 0.891 | .78 | BCOR/L1 | 0.835 | .68 | CMML1 | 0.768 | .26 | CMML1 | 0.871 | .55 |

| DDX41 | 0.663 | .39 | DDX41 | 0.577 | .26 | CMML2 | 2.644 | .018 | CMML2 | 3.460 | .0009 |

| EZH2-ASXL1 | 1.123 | .79 | EZH2-ASXL1 | 1.150 | .74 | MDS-EB | 0.954 | .82 | MDS-IB1 | 1.090 | .68 |

| IDH-STAG2 | 0.717 | .27 | IDH-STAG2 | 0.679 | .20 | MDS/AML | 1.112 | .65 | MDS-IB2 | 1.141 | .59 |

| No-event | 0.609 | .18 | No-event | 0.575 | .14 | MDS-SF3B1 | 0.237 | < .0001 | MDS-SF3B1 | 0.283 | < .0001 |

| −7/SETBP1 | 2.465 | .015 | −7/SETBP1 | 2.407 | .0180 | MDS-SLD | 0.607 | .11 | MDS-hypoplastic | 1.842 | .16 |

| SF3B1 | 0.266 | .0003 | SF3B1 | 0.271 | .0004 | MDS-TP53 | 3.353 | < .0001 | MDS–bi-TP53 | 4.307 | < .0001 |

| SRSF2 | 0.406 | .38 | SRSF2 | 0.406 | .38 | MDS-del5q | 0.393 | .02 | MDS-del5q | 0.484 | .07 |

| TP53-CK | 2.766 | .0002 | TP53-CK | 2.555 | .0008 | SCT | 0.291 | < .0001 | MDS-fibrosis | 1.366 | .55 |

| U2AF1-157 | 1.319 | .54 | U2AF1-157 | 1.283 | .58 | SCT | 0.289 | < .0001 | |||

| U2AF1-34 | 0.567 | .24 | U2AF1-34 | 0.548 | .20 | ||||||

| ZRSR2 | 3.347 | .06 | ZRSR2 | 3.452 | .05 | ||||||

| bi-TET2 | 0.479 | .0495 | bi-TET2 | 0.485 | .05 | ||||||

| Del(5q) | 0.363 | .015 | Del(5q) | 0.360 | .0147 | ||||||

| Der(1;7) | 0.532 | .54 | Der(1;7) | 0.530 | .53 | ||||||

| mNOS | 0.591 | .17 | mNOS | 0.600 | .18 | ||||||

| SCT | 0.295 | < .0001 | SCT | 0.277 | < .0001 | ||||||

| BM Blasts | 1.020 | .14 | |||||||||

| IWG class . | IWG class incl. BM blasts . | ICC . | WHO5 . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class . | HR . | P value . | Class . | HR . | P value . | Entity . | HR . | P value . | Entity . | HR . | P value . |

| AML-like | 0.319 | .12 | AML-like | 0.277 | .09 | AML | 0.627 | .52 | AML | 0.542 | .30 |

| BCOR/L1 | 0.891 | .78 | BCOR/L1 | 0.835 | .68 | CMML1 | 0.768 | .26 | CMML1 | 0.871 | .55 |

| DDX41 | 0.663 | .39 | DDX41 | 0.577 | .26 | CMML2 | 2.644 | .018 | CMML2 | 3.460 | .0009 |

| EZH2-ASXL1 | 1.123 | .79 | EZH2-ASXL1 | 1.150 | .74 | MDS-EB | 0.954 | .82 | MDS-IB1 | 1.090 | .68 |

| IDH-STAG2 | 0.717 | .27 | IDH-STAG2 | 0.679 | .20 | MDS/AML | 1.112 | .65 | MDS-IB2 | 1.141 | .59 |

| No-event | 0.609 | .18 | No-event | 0.575 | .14 | MDS-SF3B1 | 0.237 | < .0001 | MDS-SF3B1 | 0.283 | < .0001 |

| −7/SETBP1 | 2.465 | .015 | −7/SETBP1 | 2.407 | .0180 | MDS-SLD | 0.607 | .11 | MDS-hypoplastic | 1.842 | .16 |

| SF3B1 | 0.266 | .0003 | SF3B1 | 0.271 | .0004 | MDS-TP53 | 3.353 | < .0001 | MDS–bi-TP53 | 4.307 | < .0001 |

| SRSF2 | 0.406 | .38 | SRSF2 | 0.406 | .38 | MDS-del5q | 0.393 | .02 | MDS-del5q | 0.484 | .07 |

| TP53-CK | 2.766 | .0002 | TP53-CK | 2.555 | .0008 | SCT | 0.291 | < .0001 | MDS-fibrosis | 1.366 | .55 |

| U2AF1-157 | 1.319 | .54 | U2AF1-157 | 1.283 | .58 | SCT | 0.289 | < .0001 | |||

| U2AF1-34 | 0.567 | .24 | U2AF1-34 | 0.548 | .20 | ||||||

| ZRSR2 | 3.347 | .06 | ZRSR2 | 3.452 | .05 | ||||||

| bi-TET2 | 0.479 | .0495 | bi-TET2 | 0.485 | .05 | ||||||

| Del(5q) | 0.363 | .015 | Del(5q) | 0.360 | .0147 | ||||||

| Der(1;7) | 0.532 | .54 | Der(1;7) | 0.530 | .53 | ||||||

| mNOS | 0.591 | .17 | mNOS | 0.600 | .18 | ||||||

| SCT | 0.295 | < .0001 | SCT | 0.277 | < .0001 | ||||||

| BM Blasts | 1.020 | .14 | |||||||||

The analyses included SCT as a time-dependent variable for IWG class (left columns), ICC MDS entities (middle columns), and WHO5 MDS entities (right columns). BM blasts at diagnosis as a continuous variable were also included for the IWG analysis. Statistically significant entities within each classification are bolded. Reference groups: IWG: CCUS-like, ICC: MDS-MLD, WHO5: MDS-LB.

The IWG TP53-CK class includes cases with CK without biallelic TP53 lesions, whereas the ICC and WHO5 MDS-TP53 entities are restricted to cases with biallelic/multihit TP53 lesions (with the exception of ICC MDS/AML, which allows cases with a monoallelic TP53 mutation of at least 10% VAF). Within TP53-CK, 17 of 115 cases lacked any TP53 mutation and were assigned this group solely based on CK. Cases classified as MDS-TP53 by ICC or WHO5 showed significantly worse outcome than other TP53-CK cases (Figure 5), and for WHO5 showed a trend (P = .057) for enrichment in cases that were therapy-related (50% vs 29%). In a MVA of OS for TP53-CK cases that included WHO5 MDS-TP53 (defined by biallelic TP53 inactivation), SCT, and therapy-related status, WHO5 MDS-TP53 (HR, 1.753; P = .021) and SCT (HR, 0.239; P < .0001) significantly affected OS, whereas therapy-relatedness was not significant (HR, 1.275; P = .22).

OS of patients in the TP53-CK class subdivided by those classified as WHO5 MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation vs other entities and as ICC MDS with mutated TP53 vs other entities. Patients classified as WHO5 MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation or ICC MDS with mutated TP53 had significantly shorter OS than other patients in the TP53-CK class (P = .0007 and P = .0144, respectively).

OS of patients in the TP53-CK class subdivided by those classified as WHO5 MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation vs other entities and as ICC MDS with mutated TP53 vs other entities. Patients classified as WHO5 MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation or ICC MDS with mutated TP53 had significantly shorter OS than other patients in the TP53-CK class (P = .0007 and P = .0144, respectively).

Discussion

In this study, we applied a recently published IWG MDS molecular taxonomy15 to a single-institution cohort of MDS/oCMML cases. Compared with the Bernard et al cohort,15 our cohort had a higher proportion of therapy-related cases (P < .0001), and more patients treated with HMA (P < .0001), HMA/venetoclax (P < .0001), and SCT (P < .0001). This likely reflects MDS standard of care during our study period (2016-2022, compared with 1999-2016 for the Bernard et al study15). As such, our cohort provides validation of the IWG system in a recent “real-world” cohort receiving up-to-date treatment. Additionally, our cohort was restricted to cases classified as MDS by WHO4R during the study period, whereas the study by Bernard et al included significant numbers of MDS/MPN and AML cases. Upon reclassification per WHO5 and ICC, 84% and 87%, respectively, of our cohort remained as MDS, whereas only 65% and 65%, respectively, of the Bernard cohort remained as MDS (P < .0001 and P < .0001, respectively)15. The reclassified cases in our cohort were mostly oCMML, with rare cases reclassified as AML or CCUS, reflecting changes introduced for CMML and AML in WHO5/ICC.1,2 As in the Bernard et al. study, the most frequent classes in our cohort were TP53-complex, IDH-STAG2, SF3B1, No-event, bi-TET2, and mNOS, and the least frequent classes were SRSF2, ZRSR2, AML-like, and der(1;7). No-event was the fourth most common class in our cohort, reflecting that ∼10% of MDS cases have no identifiable genetic abnormalities.19 The higher proportion of TP53-CK in our cohort (29.3%) compared with the Bernard study (10.1%) likely reflects that our cases originate from a single, large cancer center; we acknowledge the limitation of potential overrepresentation of a higher-risk patient population in our cohort. The morphologically defined WHO5/ICC entities, which represented over two-thirds of our MDS cases, similar to other series,20 manifested broad variability in their genetic signatures.

There were statistically significant differences in clinical features at presentation among the molecular classes. For instance, a subset of the molecular classes (bi-TET2, EZH2-ASXL1, and CCUS-like) had significant enrichment of oCMML cases. Currently, CMML is separated from MDS by an arbitrary threshold of peripheral blood monocytes (≥0.5 × 109/L, and comprising ≥10% of white blood cells), with recent studies suggesting that these criteria classify some cases biologically related to MDS as CMML.21,22 Overall, our findings are consistent with previous reports establishing that mutations in TET2, EZH2, and ASXL1 tend to be associated more with CMML than with MDS.22,23 Our study also raises the question of whether oCMML cases that do not fall within bi-TET2, EZH2-ASXL1, or CCUS-like classes (representing 54% of the oCMML cases in our cohort) may be more appropriately classified as MDS. A recent large study of oCMML found that TET2 and ASXL1 mutations are more frequent in bona fide CMML compared with cases of oCMML, suggesting that at least the oCMML cases within bi-TET2 and EZH2-ASXL1 classes may be more biologically related to CMML than to MDS.24 Bi-TET2, overrepresented in our oCMML subset and frequent in CMML,25 displayed favorable prognosis in our MVAs.

Statistically significant differences were also seen for age, with patients in the No-event and mNOS groups being younger, and those in the bi-TET2 group being older. Within No-event, it is possible there are still unidentified recurrent mutations in younger patients, considering that MDS in children and young adults has a different genetic landscape compared with MDS occurring in older adults.26,27 In the future, whole-genome sequencing or transcriptomic analysis may subclassify No-event cases, similar to the emergence of “BCR::ABL1-like” and “ETV6::RUNX1-like” within the current classification of B-lymphoblastic leukemia.28-31 Genetic classes also varied in applications of treatments. Patients with TP53-CK class were more likely to be treated aggressively, whereas those with SF3B1 class were more likely to be treated with supportive care or low-intensity agents, such as luspatercept.32 Patients with IDH-STAG2 class were also more likely to receive HMA or more intensive agents, which may reflect awareness of the effectiveness of HMA combinations in treating IDH2-mutated MDS.33

The IWG classes had significant variation in disease trajectories, with median OS ranging from 6.3 to 101.6 months. In the MVA, this included classes based on genetic abnormalities that already define MDS subgroups in WHO5 and ICC-- SF3B1, del(5q), and TP53-CK-- but also included bi-TET2 and −7/SETBP1, with the latter having unfavorable prognosis. −7/SETBP1 (representing 4% of the entire cohort) is an example of a potential candidate for a new genetically-defined MDS subgroup, given that it is stable over time, has significantly worse OS compared with other MDS cases, and has an outcome that did not depend on marrow blasts in our cohort. In contrast, for the SF3B1 class, OS was worse with increased marrow blasts at diagnosis, supporting retaining the 5% cutoff defining MDS with SF3B1 mutation in WHO5/ICC. Interestingly, No-event showed better prognosis in cases with increased blasts, possibly reflecting more frequent use of SCT in this class for patients with increased blasts (67% SCT), compared with those with <5% blasts (23% SCT). For the No-event group, increased blasts may have been crucial in diagnosing MDS when no molecular evidence of clonality was found, resulting in many of these patients receiving SCTs with favorable long-term survivals.

We found that TP53-CK had heterogeneous outcomes, with WHO5/ICC-defined MDS-TP53 cases having worse OS compared with patients with CK only, as previously reported.34 Thus, the WHO5 and ICC MDS-TP53 entities define a worse prognosis group compared with the broader TP53-CK IWG group, despite CK MDS cases clustering together with multihit TP53 cases in the Bernard study15 and a previous study by Bersanelli et al.5 These data suggest that unsupervised clustering may fail to capture prognostic differences reflected in WHO5/ICC.1,2

Although increased blasts thresholds of 5% and 10% are used in both WHO5 and ICC, these thresholds did not significantly influence OS in the WHO5/ICC MVAs that took into account SCT. However, increased (10%-19%) blasts in the setting of oCMML was independently prognostic, suggesting that blast percentage may be important in the setting of increased peripheral blood monocytes. Further study on larger cohorts is required to determine whether this is related to the increased blast phenotype itself or to specific genetic classes overrepresented in oCMML.

An important feature of classification is stability of a disease entity over time; a general principle of the WHO5/ICC systems is that cases generally remain in the entity determined at initial diagnosis.3 We saw an overall low rate of change to a different molecular class (18%). The 1 instance in which we saw more frequent progression was in del5q, in which most patients with genetic studies at follow-up changed to TP53-CK. These findings are in line with reported progressions from monoallelic to biallelic TP53 in this context, as well as previous studies demonstrating development of TP53 mutations in wild-type TP53 MDS-del5q.35-38 Across our cohort, class progressions occurred almost exclusively during the MDS disease phase, preceding any subsequent evolution to AML. Further studies are needed to determine whether genetic class progression may aid in predicting progression to AML alongside increasing blasts.

Limitations of our study include the small number of patients within some of the molecular classes, which limited the ability to perform subanalyses in some subtypes; larger sample sizes in future studies are needed to confirm some of our findings and explore possible associations within the smaller groups. Additionally, DDX41, KMT2A-PTD, and MYC were not evaluated in 29% of the cases in our cohort, leading to possible misclassification of DDX41 and AML-like cases. Although KMT2A-PTD and MYC (both used to define the AML-like class) were very rare in the 71% of cases that were tested (1 case each), the DDX41 class comprised 3.5% of cases tested. In DDX41, 7 of 10 cases had no additional mutations or cytogenetic aberrations, so it is possible that a small subset of No-event cases were misclassified DDX41 cases. We also did not evaluate TET2 copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (cnLOH), leading to potential underestimation of bi-TET2 cases. Finally, although our single-institution cohort reflects relatively consistent diagnostic practices and treatment algorithms, our cohort reflects case complexities and therapy decisions made solely at our single cancer referral and treatment center.

In summary, we found that the IWG MDS molecular classification could be applied in routine practice using karyotyping and clinical NGS panels. Molecular classes tended to be stable over time and exhibited several statistically significant differences in clinicopathologic features and outcomes in our cohort. Although we continue to recognize the value of morphologic evaluation, particularly in low-resource settings in which genetic data may not be available, we believe that studying MDS molecular subgroups offers the opportunity to refine classification schemes. One should consider whether the main aim of a diagnostic scheme should be to group based on underlying biology (as is now the case for B-lymphoblastic leukemia and AML) rather than the clinical phenotype or predicted outcome. Biological classification allows for consideration of new therapeutic avenues, or application of existing ones, such as IDH inhibitors for patients with IDH-STAG2. A recent MDS/CMML study showed variable HMA responses across IWG molecular classes, with higher response rates in bi-TET2 than CCUS-like.39 Additionally, a genetically-based classification system may be more reproducible than one relying largely on morphology, given interobserver variability in determining single vs multilineage dysplasia,9 BM fibrosis grade,40 and blast/promonocyte percentages.41 Rather than major classifiers, morphologic features such as blast percentage could instead serve as qualifiers to genetic disease classes and might have different impacts depending on the genetic group. In conclusion, the results of this study support that the IWG molecular taxonomy represents a step forward in identifying MDS genetic subtypes with distinct clinical trajectories, and that this taxonomy may help inform future MDS classification systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, clinical teams, and pathologists involved in the cases analyzed.

This study did not receive any specific funding.

Authorship

Contributions: R.G. and R.P.H. contributed to the study conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript; L.Y. and M.R. contributed to data collection; B.J.A. and A.M.B. contributed to data analysis; and all authors contributed to manuscript review and editing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.P.H. has received consulting fees from Servier, Inc. A.M.B has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Novartis, Geron, Rigel, Keros, and Sydnax. B.J.A. receives distribution of royalty payments relating to venetoclax from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Melbourne, Australia. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert P. Hasserjian, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit St, Boston, MA 02114; email: rhasserjian@partners.org.

References

Author notes

Parts of this manuscript were presented in abstract form at the 114th annual meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Boston, MA, 24 March 2025, which was awarded the 2025 Society for Hematopathology Pathologist-in-Training award.

The data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Robert P. Hasserjian (rhasserjian@partners.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.