Key Points

Patient-derived iPSC models of KMT2A-rearranged AML reveal transcriptional rewiring of HSPCs driven by Polycomb-mediated silencing.

PRC2 inhibition restores epigenetic and transcriptional balance in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML, reducing the leukemic phenotype.

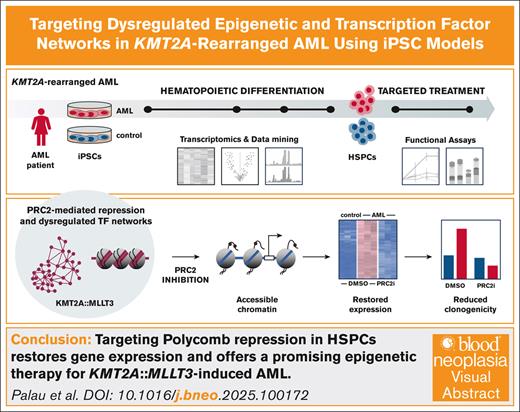

Visual Abstract

KMT2A chromosomal rearrangements (KMT2A-r) are frequent in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and are associated with poor prognosis. The KMT2A gene encodes a histone lysine methyltransferase responsible for maintaining active chromatin marks (H3K4me3) at gene promoters and enhancers. KMT2A-r lead to the formation of oncogenic KMT2A fusion proteins with over 70 potential partners, disrupting normal hematopoiesis and driving leukemogenesis. Among these, KMT2A::MLLT3, a fusion of KMT2A and MLLT3, is one of the most prevalent in AML. Disruption of the epigenome is a hallmark of AML, with recurrent abnormalities in epigenetic regulators. These alterations often occur early as disease-initiating events, making epigenetic-targeted therapeutics a promising avenue for treatment. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have emerged as faithful models of human AML pathogenesis, recapitulating the underlying genomic lesions and epigenetic profiles. We investigated transcriptional regulation of hematopoietic development using iPSCs derived from a patient with AML with the KMT2A::MLLT3 rearrangement. Our analysis identified key transcriptional activators and repressors that contribute to the altered regulatory landscape in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML. Further analysis of chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing data indicated that a significant subset of genes, whose expression was downregulated in AML iPSC-derived hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (AML-HSPCs), were direct targets of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2). Treatment with the dual EZH1/2 inhibitor UNC1999 and 5-azacytidine reactivated these PRC2 target genes, specifically in AML-HSPCs, toward normal gene expression patterns. These findings suggest that targeting Polycomb repression offers a promising epigenetic strategy for improving outcomes in KMT2A-rearranged AML.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with KMT2A chromosomal rearrangements (KMT2A-r) affects both adults and children but is significantly more prevalent among younger patients and represents the most common genetic alteration in infants. The KMT2A gene encodes the histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methyltransferase KMT2A (MLL), which maintains active expression at promoters and enhancers. KMT2A-r result in oncogenic fusion proteins with numerous fusion partners, most commonly members of the elongation machinery such as AF9, encoded by MLLT3. Although clinical outcomes partly depend on the fusion partner, KMT2A-r is generally considered a dismal prognostic factor, characterized by resistance to chemotherapy and high rates of relapse.1

A network of epigenetic factors relays information to the transcriptional program, guiding the fate and differentiation of hematopoietic cells. It has been suggested that early aberrant epigenetic changes in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), which are caused by mutations in epigenetic regulators or chromosomal rearrangements, create epigenetic heterogeneity and cellular vulnerability, thereby increasing the probability of leukemic development. Accordingly, abnormalities in epigenetic and transcriptional regulators are among the most recurrent events in AML, frequently constituting early and disease-initiating lesions.2 Epigenetic-targeted therapeutics may be effective when incorporated into treatment strategies to diminish transcriptional adaptation in rearranged or mutant HSPCs. Importantly, epigenetic therapy has much milder side effects than conventional cytotoxic drugs,3,4 making it highly suitable for the treatment of pediatric cancer. However, an increased understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of AML is necessary to target the process therapeutically.

The lack of physiologically accurate human models to study AML limits mechanistic insights and hampers the identification of novel therapeutic targets. Isolated primary cells from bone marrow or peripheral blood are heterogeneous, have limited ex vivo expansion potential, exhibit poor long-term survival, and present technical challenges. Alternatively, immortalized cell lines are more readily manipulated in vitro, but they often harbor additional genetic lesions or cytogenetic abnormalities, which can confound experimental results. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have become increasingly valuable as experimental models of hematopoietic malignancies. They can capture somatic driver mutations, are amenable to genetic manipulations, and can generate unlimited disease-critical differentiated cells.5-8 Notably, iPSC reprogramming of AML blasts erases the specific epigenetic profile of the cell of origin; however, this profile is regained when differentiated into the relevant cell type.5 Hence, iPSCs represent personalized stem cell models that empower mechanistic studies and functional readouts beyond the capacity of other model systems.

Here, we aimed to use these models to identify transcription factor (TF) networks and epigenetic regulators involved in the development of KMT2A-rearranged AML, which may be exploited for treatment. To investigate differences in gene expression and transcriptional regulation, mutant and isogenic wild-type iPSC lines, generated from a patient with AML with a KMT2A::MLLT3 rearrangement, were directed toward hematopoietic cells and analyzed in the context of differentiation. Transcriptional profiling using cap analysis of gene expression (CAGE) showed that AML cells exhibited an aberrant gene expression profile, characterized by delayed activation or persistent repression of genes regulated by a TF network and the Polycomb Repressive Complex (PRC). Within this framework, we uncovered a set of transcriptional activators and repressors, including SPI1, MYC, and NFYA, underlying the disrupted regulatory landscape in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML. The targeted inhibition of the PRC2 member EZH2 and DNMT derepressed a large subset of these genes and partially restored a normal expression profile. In addition, drug treatment of HSPCs and leukemic cell lines selectively targeted KMT2A::MLLT3 cells and reduced AML cell number and self-renewal capacity in colony-forming assays. Collectively, our findings support a model of cell-intrinsic epigenetic suppression of the hematopoietic phenotype in KMT2A::MLLT3 rearrangement, which may be reversed upon EZH2 inhibition.

Methods

FISH and LD-RT-PCR

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) visualization of the KMT2A translocation was performed in AML-iPSCs (clone AML 1.2) and control-iPSCs. Samples were hybridized with the Vysis MLL Dual Color Break Apart Rearrangement Probe (05J90-001; Abbott). Ligation-dependent reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (LD-RT-PCR) was performed, as previously described,9 starting from 2 μL of RNA.

Cell culture, hematopoietic differentiation, and drug treatment

iPSCs were cultured on Matrigel hESC-qualified Matrix (Corning) in mTeSR Plus (STEMCELL Technologies) and passaged as clumps using EZ-LiFT Stem Cell Passaging Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). For CAGE time course experiments, control- and AML-iPSCs were differentiated into HSPCs following the protocol from Chao et al,5 and triple-positive (CD34+CD43+CD45+) cells were sorted on days 8, 10, and 12 of differentiation. For all other experiments, control- and AML-iPSCs were differentiated into HSPCs using STEMdiff Hematopoietic Kit (STEMCELL Technologies) or a 13-day protocol based on Matsubara et al,10 with the addition of interleukin-3 (IL-3; 50 ng/mL) from day 4 to 13. HSPCs were harvested, expanded, and drug-treated for 72 hours in StemSpan SFEM II medium (STEMCELL Technologies), penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; 1%), stem cell factor (SCF; 50 ng/mL), IL-3 (50 ng/mL), thrombopoietin (TPO; 50 ng/mL), FMS-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3L; 50 ng/mL), and IL-6 (10 ng/mL). Cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 1:2000) as vehicle; 5-azacytidine (AZA; 1 μM); UNC1999 (2 or 5 μM); or UNC1999 (2 μM) + AZA (1 μM). Additional methodologies are provided in the supplemental Methods.

RNA transcriptomics (CAGE and RNA-seq)

For CAGE and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments, RNA was extracted from cells using miRNeasy Micro Kit (n = 4; Qiagen) and AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (n = 3; Qiagen). Total RNA was subjected to quality control with Agilent TapeStation according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To construct libraries suitable for Illumina sequencing, the Illumina stranded messenger RNA prep ligation sample preparation protocol was used with starting concentration between 25 and 1000 ng of total RNA. The protocol included messenger RNA isolation, complementary DNA synthesis, ligation of adapters, and amplification of indexed libraries. Library yield was quantified using Qubit fluorometry (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and quality was assessed using the Agilent TapeStation. The indexed complementary DNA libraries were normalized and combined, and the pools were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 2000 P2 100 cycle sequencing run, generating paired-end 2 × 58 base pair (bp) reads with dual indexing. MOIRAI pipeline was used to process the raw sequencing data.11 Uniquely mapped reads were then overlapped with the FANTOM5 robust promoter set.12

Motif activity response analysis and protein interaction network analysis

Motif activity response analysis (MARA) was performed to assess the region spanning –300 bp to +100 bp relative to the representative CAGE peak at the promoter, as previously described.13 Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interatcting Genes/Proteins (STRING) network analysis was performed with version 12.0 on the web-based application at https://string-db.org/. Relevant protein names were inputted to “List of Names”, and “Homo sapiens” was specified as the organism in the search arguments for “Multiple proteins”. Default parameters were then used to query STRING-db to obtain a full STRING network.

Results

Hematopoietic differentiation of KMT2A-rearranged iPSCs is associated with a distinct transcriptional profile

To gain increased insight into the development and therapeutic vulnerability of AML, we studied hematopoietic differentiation in the context of KMT2A-r using iPSCs previously established from a patient with AML (AML-iPSC) with a KMT2A::MLLT3 translocation.5 The KMT2A-r was validated in the AML-iPSCs using FISH and isogenic wild-type iPSCs as a negative control (supplemental Figure 1A). Furthermore, we confirmed the rearrangement of KMT2A exon 11 and MLLT3 exon 6 to be present exclusively in the AML-iPSCs through LD-RT-PCR amplification (supplemental Figure 1B).

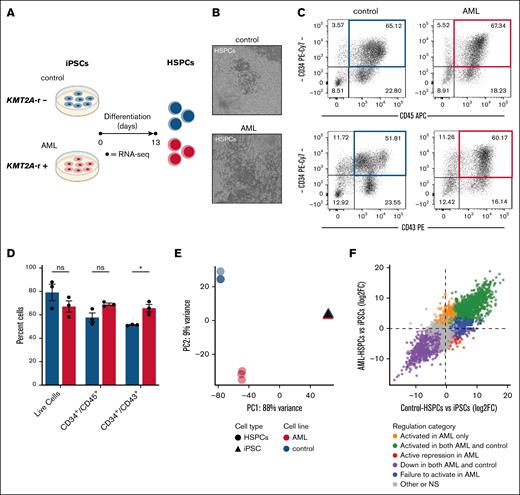

To characterize the effect of KMT2A::AF9 at the HSPC stage, we differentiated AML- and control-iPSCs into hematopoietic progenitor cells (Figure 1A-B) and analyzed surface marker expression via flow cytometry. Hematopoietic differentiation was robust across both AML and control cell lines, with comparable viability and HSPC potential (Figure 1C-D). Flow cytometry analysis revealed a significantly lower frequency of CD34+/CD43+ cells derived from control-iPSCs, as AML cells retained expression of the early HSPC marker CD34 at the analyzed time point. Subsequently, we assessed the transcriptional profiles of iPSCs and HSPCs from AML and controls by performing RNA-seq. Principal component analysis revealed that AML and control cells clustered together at the iPSC stage, indicating a shared transcriptomic profile. Conversely, HSPCs derived from AML-iPSCs clustered separately from control cells, which suggests that KMT2A::AF9-associated transcriptional dysregulation is present at the HSPC stage (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 2A).

Hematopoietic specification of KMT2A-rearranged iPSCs induces a transcriptionally distinct profile. (A) Schematic of the generation of HSPCs from AML- and control-iPSC cell lines. (B) Representative images of hematopoietic cultures of control- and AML-iPSCs depicting the generation of HSPCs following 13 days of differentiation. (C) Representative flow cytometry diagrams of hematopoietic cell populations from control- and AML-HSPCs after 13 days of differentiation, and (D) quantification of the viability and expression of key hematopoietic populations by flow cytometry (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of percent cells in hematopoietic cultures and analyzed using unpaired t test with Holm-Šídák multiple comparisons test. (E) Principal component analysis plot from RNA-seq of iPSCs (triangles) and day 13 HSPCs (circles) from AML and control cell lines, showing the first 2 principal components (n = 3). (F) Scatterplot of differential expression during hematopoietic differentiation, comparing log2 fold changes (HSPCs vs iPSCs) in control (x-axis) and AML (y-axis). Genes were classified into categories including activated in both AML and control (green), activated in AML only (orange), actively repressed in AML (red), failed to activate in AML (blue), downregulated in both AML and control (purple), and ns/other (gray). ∗P ≤ .05. ns, not significant.

Hematopoietic specification of KMT2A-rearranged iPSCs induces a transcriptionally distinct profile. (A) Schematic of the generation of HSPCs from AML- and control-iPSC cell lines. (B) Representative images of hematopoietic cultures of control- and AML-iPSCs depicting the generation of HSPCs following 13 days of differentiation. (C) Representative flow cytometry diagrams of hematopoietic cell populations from control- and AML-HSPCs after 13 days of differentiation, and (D) quantification of the viability and expression of key hematopoietic populations by flow cytometry (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of percent cells in hematopoietic cultures and analyzed using unpaired t test with Holm-Šídák multiple comparisons test. (E) Principal component analysis plot from RNA-seq of iPSCs (triangles) and day 13 HSPCs (circles) from AML and control cell lines, showing the first 2 principal components (n = 3). (F) Scatterplot of differential expression during hematopoietic differentiation, comparing log2 fold changes (HSPCs vs iPSCs) in control (x-axis) and AML (y-axis). Genes were classified into categories including activated in both AML and control (green), activated in AML only (orange), actively repressed in AML (red), failed to activate in AML (blue), downregulated in both AML and control (purple), and ns/other (gray). ∗P ≤ .05. ns, not significant.

To further characterize these transcriptional differences, we classified genes based on their regulation in AML and control differentiation (Figure 1F). This analysis showed that although many genes were concordantly regulated between AML and control, a distinct subset was aberrant in AML, including genes that were actively repressed (n = 239), failed to activate (n = 1421), or uniquely activated (n = 1303) in AML. Overrepresentation analysis of the repressed categories revealed significant enrichment of gene sets involved in myeloid differentiation, as well as downregulated genes following NUP98::HOXA9 fusion expression, suggesting transcriptional silencing of lineage programs and leukemia-associated regulation (supplemental Figure 2B). All these results demonstrate that although iPSCs appear unaffected by KMT2A::MLLT3, HSPCs exhibit significant transcriptional aberrations, underscoring the importance of understanding stage-specific differences in gene regulation for potential therapeutic targeting.

Hematopoiesis in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML is regulated by a distinct network of TFs

To identify TF regulatory networks in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML, we specified AML- and control-iPSCs toward hematopoietic cells and collected populations at 0, 8, 10, and 12 days of differentiation (Figure 2A). Transcriptional analysis was performed using CAGE methodology, which facilitates high-throughput gene expression analysis with simultaneous mapping of transcriptional start sites and corresponding promoter regions.14 We observed a time-dependent deregulation of transcription during hematopoietic specification from AML-iPSCs (Figure 2B), reflecting our previous observations. Specifically, a subset of genes was aberrantly repressed, showing either a delay in expression or continuous repression in AML cells compared with wild-type control cells.

PRC2 members associate with repressed genes in AML-HSPCs. (A) Schematic of hematopoietic differentiation of control- and AML-iPSCs with days indicating time points at which samples were harvested for CAGE sequencing. (B) Heat map showing unsupervised clustering of the 100 most variable genes in control- and AML-iPSCs during hematopoietic specifications with cells harvested at the indicated time points (n = 4). (C) Heat map depicting dynamic changes in motif activity in promoters between control- and AML-iPSC differentiation as inferred from CAGE data using MARA. (D) Individual motif activity profiles of ARNT_ARNT2_BHLHB2_MAX_MYC_USF1; ETS1,2; LMO2; TFCP2; SNAI1..3; SPI1; NFY(A,B,C); and ZEB1 promoters between control and AML differentiation as inferred from CAGE data using MARA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using unpaired t test for each time point. (E) Box plots showing expression levels (log2[CPM + 1]) of MYC and NFYA from RNA-seq of control and AML cells at iPSC and HSPC stages. Boxes represent interquartile range with whiskers extending to 1.5× interquartile range and horizontal lines denoting median values. Outliers are shown as individual points. Adjusted P values (FDR) derived from DESeq2 results. (F) Heat map of unsupervised clustering of candidate ChIP-seq signatures from ChIP-Atlas, showing differential patterns between control- and AML-HSPCs across days 8, 10, and 12 of hematopoietic differentiation. (G) STRING network of TFs with differential motif activity and direct interaction to PRC1/2 members (circled in black). Nodes in the network represent proteins, and edges represent predicted associations based on various sources of evidence, which include curated databases (light blue), performed experiments (purple), text-mining (yellow), coexpression (black), and homology (dark blue). ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. ns, not significant; CPM, counts per million; FDR, false discovery rate; TPM, transcripts per million.

PRC2 members associate with repressed genes in AML-HSPCs. (A) Schematic of hematopoietic differentiation of control- and AML-iPSCs with days indicating time points at which samples were harvested for CAGE sequencing. (B) Heat map showing unsupervised clustering of the 100 most variable genes in control- and AML-iPSCs during hematopoietic specifications with cells harvested at the indicated time points (n = 4). (C) Heat map depicting dynamic changes in motif activity in promoters between control- and AML-iPSC differentiation as inferred from CAGE data using MARA. (D) Individual motif activity profiles of ARNT_ARNT2_BHLHB2_MAX_MYC_USF1; ETS1,2; LMO2; TFCP2; SNAI1..3; SPI1; NFY(A,B,C); and ZEB1 promoters between control and AML differentiation as inferred from CAGE data using MARA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using unpaired t test for each time point. (E) Box plots showing expression levels (log2[CPM + 1]) of MYC and NFYA from RNA-seq of control and AML cells at iPSC and HSPC stages. Boxes represent interquartile range with whiskers extending to 1.5× interquartile range and horizontal lines denoting median values. Outliers are shown as individual points. Adjusted P values (FDR) derived from DESeq2 results. (F) Heat map of unsupervised clustering of candidate ChIP-seq signatures from ChIP-Atlas, showing differential patterns between control- and AML-HSPCs across days 8, 10, and 12 of hematopoietic differentiation. (G) STRING network of TFs with differential motif activity and direct interaction to PRC1/2 members (circled in black). Nodes in the network represent proteins, and edges represent predicted associations based on various sources of evidence, which include curated databases (light blue), performed experiments (purple), text-mining (yellow), coexpression (black), and homology (dark blue). ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. ns, not significant; CPM, counts per million; FDR, false discovery rate; TPM, transcripts per million.

TFs regulate gene expression by binding promoter-proximal DNA elements. We applied MARA to model TF regulatory networks underlying gene expression profiles during hematopoietic differentiation.13 MARA combines the prediction of TF binding sites with mathematical modeling of changes in gene expression to calculate the significance of TF binding sites in driving observed gene expression patterns. Our MARA analysis revealed no major differences in motif activity between AML and wild-type cells at the pluripotent stem cell stage (day 0 of differentiation; Figure 2C). However, significant differential TF motif activity was shown at the HSPC stage at all analyzed time points (days 8, 10 and 12; Figure 2C; supplemental Table 2), including both transcriptional activators and repressors. A number of TF motifs, including ETS1/2 and SPI1, displayed reduced activity in HSPCs derived from AML-iPSCs (AML-HSPCs) compared to HSPCs derived from wild-type control iPSCs (control-HSPCs; Figure 2C-D). Other motifs, such as NFY, LMO2, MYC, and ZEB1, showed continuous activity throughout differentiation in AML cells, whereas they became progressively repressed in normal hematopoiesis (Figure 2D).

To uncover the direct targets of KMT2A::AF9 among TFs in the regulatory network, we assessed a publicly available KMT2A::AF9 chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data set.15 Notably, this analysis identified MYC and NFYA as direct targets of KMT2A::AF9 (supplemental Figure 3A). We further examined NFYA using a CUT&Tag data set from 5 patients with KMT2A-rearranged AML,16 which demonstrated binding of both the C- and N-terminal regions of KMT2A at the NFYA promoter (supplemental Figure 3B). These results support NFYA as a bona fide target of KMT2A and potentially of KMT2A::AF9. Given that KMT2A::AF9 binding has been shown to activate transcription of target genes,17,18 we then asked whether MYC and NFYA expression reflected this regulatory effect in our model. RNA-seq analysis demonstrated that although the expression of MYC and NFYA decreased over hematopoietic differentiation in control cells, their levels increased with differentiation in AML and were significantly higher in AML-HSPCs than in control-HSPCs (Figure 2E). NFYB and NFYC, which encode subunits of the trimer that lack sequence specificity, unlike the DNA-binding NFYA,19 were not upregulated in AML-HSPCs (supplemental Figure 3C), suggesting that NFYA may serve as the key regulatory subunit in this context. The analysis of ENCODE NFYA ChIP-seq data from K562 cells20 (supplemental Table 3) revealed 122 of the 1303 genes selectively activated in AML-HSPCs were NFYA targets. Notably, several of these genes regulate processes central to leukemogenesis, including cell cycle activation (eg, GAS2,21 MTFR2,22 E2F3,23 CDK2,24 and SEC23B25) and inhibition of apoptosis (eg, BCL2L1326 and FKBP827), suggesting that NFYA activation may contribute to KMT2A::AF9-driven AML. In summary, we observed an active transcriptional repression of a subset of genes and significant differences in TF motif activity during hematopoietic differentiation of AML cells and found evidence that KMT2A::AF9 engages NFYA, whose motif activity and expression remain elevated in AML-HSPCs.

Polycomb complex regulates the repressed gene expression profile in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML

We next sought to determine whether the signature of transcriptional repression observed in AML-HSPCs was connected to the repressive epigenetic machinery. To identify epigenetic regulators that bind to the dysregulated genes identified in our CAGE analysis, we performed ChIP-seq analysis using publicly available ChIP-seq databases.28 Members of the PRCs (PRC1 and PRC2) were prominently represented among the 100 most variable ChIP-seq signatures (supplemental Figure 4). Target genes of PRC-associated repressors, including JARID2, BMI1, and EZH2, displayed lower ChIP-Atlas scores in AML (Figure 2F), suggesting that PRC1 and PRC2 targets are transcriptionally repressed in AML-HSPCs relative to control-HSPCs. In addition, the target genes of DNA methyltransferases DNMT3B and DNMT1 showed high variability. These findings suggest that the repressed expression profile observed during hematopoietic specification in AML with KMT2A::MLLT3 is regulated by PRC1, PRC2, and DNMTs. To further investigate this aspect, we performed STRING analysis to explore the protein-protein interactions between the identified TFs (Figure 2C) and PRC1/2 members. This protein interaction network analysis showed that 18 TFs with altered motif activity in AML-HSPCs interact with PRC1/2 members (Figure 2G; supplemental Table 2), which suggests that these TFs and PRC1/2 form a regulatory network. All these results demonstrate that the epigenetic regulators PRC1 and PRC2 may play a critical role in the repressed gene expression profile and development of AML with KMT2A::MLLT3 and form a regulatory network with dysregulated TFs in AML-HSPCs.

PRC2 inhibition selectively impairs clonogenicity in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML cells

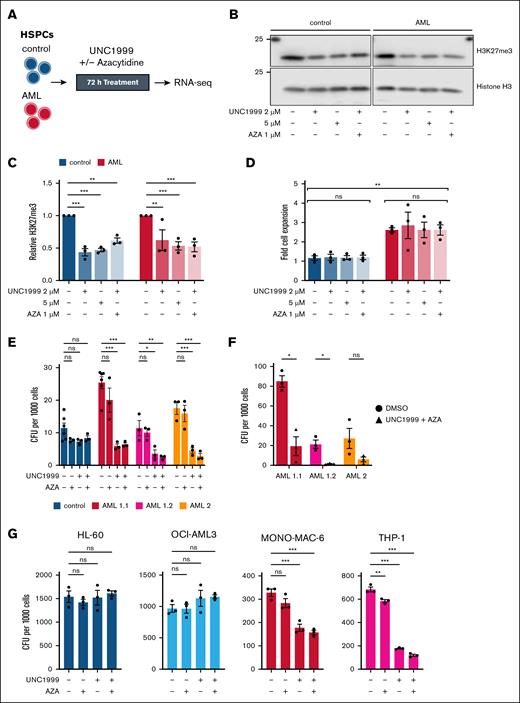

Our MARA and ChIP signature analyses implicated Polycomb-mediated repression in KMT2A::MLLT3 leukemogenesis and suggested that PRC-dependent repression acts as a barrier to differentiation in AML cells. To test this notion, we treated AML- and control-HSPCs with the dual EZH1/2 inhibitor UNC199929 for 72 hours in a hematopoietic expansion medium, with or without the DNMT inhibitor AZA, given the dysregulation of DNMT-regulated loci (Figures 2F and 3A). Immunoblotting results showed that UNC1999 alone and combined with AZA reduced global H3K27me3 levels compared with DMSO-treated controls, consistent with on-target PRC2 inhibition (Figure 3B-C). After 72 hours, AML-HSPC fold expansion was significantly higher than that in control cultures, consistent with a leukemic phenotype but neither UNC1999 nor UNC1999 + AZA significantly affected cell proliferation at this time point (Figure 3D).

Epigenetic targeting selectively impairs clonogenicity in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML cells. (A) Experimental overview for the inhibition of PRC2 by UNC1999 and DNA methylation by AZA in control- and AML-HSPCs. (B) Representative immunoblot analysis and (C) quantification of relative H3K27me3 protein levels in HSPCs from control- and AML-iPSCs after 72 hours of treatment with 2 μM and 5 μM UNC1999, 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA, or DMSO (n = 3). Histone H3 was used to calculate relative H3K27me3 levels, which were normalized to control DMSO conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of relative signal and analyzed using 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett multiple comparisons test. (D) Fold cell expansion of HSPCs from control- and AML-iPSC cells lines following 72 hours of treatment with 2 μM and 5 μM UNC1999, 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA, or DMSO relative to cell number at seeding (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of fold cell expansion. Lines indicate comparisons within and between control and AML cells. Data were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. (E) CFU counts per 1000 seeded HSPCs treated with 2 μM UNC1999, 1 μM AZA, 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA, or DMSO for 14 days (n = 6 for DMSO in AML 1.1 and control, n = 3 for others). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple comparisons test. (F) CFU counts per 1000 replated AML cells from panel E after 10 days in methylcellulose without treatment (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using unpaired t test with Holm-Šídák multiple comparisons test. (G) CFU counts per 1000 seeded cells from leukemic cell lines treated with 2 μM UNC1999, 1 μM AZA, 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA, or DMSO for 10 days (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple comparisons test. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. ns, not significant.

Epigenetic targeting selectively impairs clonogenicity in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML cells. (A) Experimental overview for the inhibition of PRC2 by UNC1999 and DNA methylation by AZA in control- and AML-HSPCs. (B) Representative immunoblot analysis and (C) quantification of relative H3K27me3 protein levels in HSPCs from control- and AML-iPSCs after 72 hours of treatment with 2 μM and 5 μM UNC1999, 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA, or DMSO (n = 3). Histone H3 was used to calculate relative H3K27me3 levels, which were normalized to control DMSO conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of relative signal and analyzed using 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett multiple comparisons test. (D) Fold cell expansion of HSPCs from control- and AML-iPSC cells lines following 72 hours of treatment with 2 μM and 5 μM UNC1999, 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA, or DMSO relative to cell number at seeding (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of fold cell expansion. Lines indicate comparisons within and between control and AML cells. Data were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test. (E) CFU counts per 1000 seeded HSPCs treated with 2 μM UNC1999, 1 μM AZA, 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA, or DMSO for 14 days (n = 6 for DMSO in AML 1.1 and control, n = 3 for others). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple comparisons test. (F) CFU counts per 1000 replated AML cells from panel E after 10 days in methylcellulose without treatment (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using unpaired t test with Holm-Šídák multiple comparisons test. (G) CFU counts per 1000 seeded cells from leukemic cell lines treated with 2 μM UNC1999, 1 μM AZA, 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA, or DMSO for 10 days (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple comparisons test. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. ns, not significant.

We next evaluated the impact of PRC2 and DNMT inhibition on colony-forming unit (CFU) ability following 14 days of treatment. AML-HSPCs derived from 2 independent clones from the KMT2A::MLLT3 patient (AML 1.1 and AML 1.2), as well as 1 clone from a second KMT2A::MLLT3 patient (AML 2) were cultured with combinations of UNC1999 and AZA. Although AZA alone did not significantly affect CFU numbers (supplemental Figure 5A), UNC1999 alone and in combination with AZA reduced CFU formation in all 3 AML-HSPC clones. In contrast, control-HSPCs showed no significant change compared to DMSO-treated cells (Figure 3E). Upon harvest and replating into untreated methylcellulose, prior exposure to UNC1999 + AZA impaired AML colony self-renewal relative to DMSO, with significant reductions observed in 2 of the 3 AML clones (Figure 3F) and comparable effects across all AML lines (supplemental Figure 5B). The robust and consistent impairment of clonogenic capacity in distinct AML-HSPC clones highlights the reproducibility of this response in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML.

To further examine the specificity of PRC2 inhibition in KMT2A::MLLT3-rearranged cells, we performed CFU assays in AML cell lines harboring either wild-type KMT2A (HL-60 and OCI-AML3) or the KMT2A::MLLT3 fusion (THP-1 and MONO-MAC-6). PRC2 inhibition reduced clonogenic growth in KMT2A-rearranged cell lines, with no significant effect observed in wild-type KMT2A cells (Figure 3G; supplemental Figure 5C), paralleling the response observed in iPSC-derived HSPCs. Together, we demonstrate that PRC2 inhibition with UNC1999 selectively limits clonogenic potential in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML cells, while sparing KMT2A wild-type cells. These findings provide functional support that KMT2A-rearranged AML relies on PRC-mediated gene repression and suggest a favorable therapeutic window for epigenetic targeting in this context.

Treatment with PRC2 and DNMT inhibitors unlocks repression of bivalent genes in AML-HSPCs

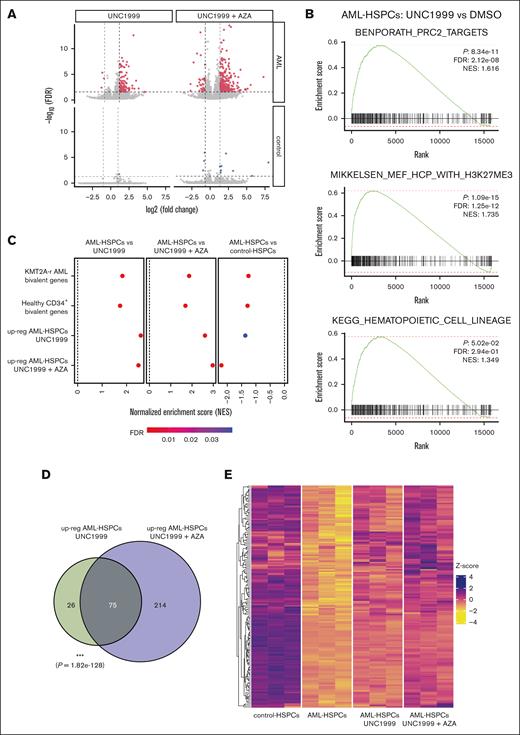

We next sought to characterize the early transcriptional effects of our pharmacological treatment. HSPCs were collected after 72 hours of exposure to UNC1999 alone or in combination with AZA, both conditions previously shown to impair CFU ability. RNA-seq analysis revealed minimal changes in gene expression in control-HSPCs under either treatment condition (UNC1999 alone: 1 upregulated, 0 downregulated; UNC1999 + AZA: 8 upregulated, 3 downregulated; Figure 4A). In contrast, AML-HSPCs treated with UNC1999 alone exhibited 101 upregulated and 3 downregulated genes, whereas cotreatment with AZA resulted in 289 upregulated and 35 downregulated genes. Notably, the expression of HOX and MEIS1, genes characteristically upregulated in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML (supplemental Figure 6A), remained unaffected by the 72-hour drug exposure (supplemental Figure 6B). Collectively, drug treatment resulted in the induction of gene expression in AML cells, consistent with the inhibition of transcriptional repressors PRC2 and DNMT. We further explored whether altered expression of PRC2 components contributed to the drug-specific response of AML-HSPCs. All PRC2 core members (SUZ12, EED, EZH1, and EZH2) were expressed at lower levels in AML-HSPCs than in controls (supplemental Figure 6C), suggesting that reduced PRC2 activity may underlie the heightened sensitivity to PRC2 inhibition. All these results demonstrate transcriptional upregulation in response to PRC2 and DNMT inhibition, specifically in KMT2A::MLLT3 AML cells.

PRC2 inhibition derepresses transcription of Polycomb target genes downregulated in AML-HSPCs. (A) Volcano plot displaying differentially expressed genes identified using DESeq2 in AML- (red) and control- (blue) HSPCs, following 72 hours of treatment with 2 μM UNC1999 (left) or 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA (right) compared with treatment with DMSO (n = 3). Dashed lines denote cutoffs for the significance threshold (FDR = 0.05, horizontal; |log2(fold change)| = 1, vertical). (B) GSEA plots comparing gene expression profiles between differentiated AML-HSPCs treated with UNC1999 or DMSO for 72 hours. (C) Dot plots displaying NES scores from GSEA using ranked gene expression changes in AML-HSPCs treated with UNC1999, UNC1999 + AZA, or in untreated vs control-HSPCs. Gene sets tested include genes upregulated following treatment, as well as genes marked by H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 (bivalent) (D) Venn diagrams showing the overlap of upregulated genes in AML-HSPCs treated with UNC1999 (left) or UNC1999 + AZA (right) compared with those treated with DMSO. (E) Heat map showing row-wise z scores of log2(CPM) expression values of 154 upregulated genes in AML-HSPCs treated with 2 μM UNC1999 or 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA that overlap with genes downregulated in DMSO-treated control-HSPCs. ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. CPM, counts per million; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score.

PRC2 inhibition derepresses transcription of Polycomb target genes downregulated in AML-HSPCs. (A) Volcano plot displaying differentially expressed genes identified using DESeq2 in AML- (red) and control- (blue) HSPCs, following 72 hours of treatment with 2 μM UNC1999 (left) or 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA (right) compared with treatment with DMSO (n = 3). Dashed lines denote cutoffs for the significance threshold (FDR = 0.05, horizontal; |log2(fold change)| = 1, vertical). (B) GSEA plots comparing gene expression profiles between differentiated AML-HSPCs treated with UNC1999 or DMSO for 72 hours. (C) Dot plots displaying NES scores from GSEA using ranked gene expression changes in AML-HSPCs treated with UNC1999, UNC1999 + AZA, or in untreated vs control-HSPCs. Gene sets tested include genes upregulated following treatment, as well as genes marked by H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 (bivalent) (D) Venn diagrams showing the overlap of upregulated genes in AML-HSPCs treated with UNC1999 (left) or UNC1999 + AZA (right) compared with those treated with DMSO. (E) Heat map showing row-wise z scores of log2(CPM) expression values of 154 upregulated genes in AML-HSPCs treated with 2 μM UNC1999 or 2 μM UNC1999 + 1 μM AZA that overlap with genes downregulated in DMSO-treated control-HSPCs. ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. CPM, counts per million; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score.

To further characterize the AML-specific transcriptional response upon drug treatment, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on genes ranked by their differential expression following UNC1999 treatment. GSEA revealed an enrichment of PRC2 target genes and genes marked by the PRC2-mediated histone modification H3K27me3 (Figure 4B, upper and middle panels), as expected. Notably, the upregulated gene set also showed enrichment for genes involved in hematopoiesis (Figure 4B, lower panel), suggesting a potential reactivation of lineage-specific transcriptional programs in AML-HSPCs.

To investigate the epigenetic regulation of these upregulated genes in clinically relevant context, we leveraged publicly available CUT&RUN data, which profiled H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 in CD34+ HSPCs from normal bone marrow and in patients with AML harboring KMT2A-r.13,16 We focused on these histone marks because their co-occurrence is indicative of bivalent chromatin. Genes upregulated following UNC1999 or UNC1999 + AZA treatment in AML-HSPCs showed strong positive enrichment for bivalent chromatin marks in both healthy CD34+ cells and samples of patients with AML (Figure 4C).

To determine whether treatment with UNC1999 or UNC1999 + AZA could reverse the repressed gene signature in AML-HSPCs, we performed GSEA comparing genes upregulated by treatment to those downregulated in AML-HSPCs relative to control-HSPCs. Both UNC1999 and UNC1999 + AZA treatment showed strong positive enrichment for the repressed gene set (Figure 4C), indicating that Polycomb inhibition preferentially restores the expression of genes previously silenced in AML. Notably, a substantial fraction of these genes (n = 75) was consistently upregulated across both treatment conditions (Figure 4D), reflecting a convergent transcriptional response to PRC2 inhibition aimed at restoring disrupted gene expression profiles. To illustrate this effect at the gene level, we visualized the expression patterns of genes that were downregulated in AML-HSPCs but reexpressed following treatment (Figure 4E). Importantly, this restorative effect extended beyond the overlapping genes, as UNC1999 + AZA treatment reactivated a broader subset of AML-repressed genes (supplemental Figure 7). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that treatment with UNC1999 alone or in combination with AZA leads to the upregulation of PRC2 target genes and bivalent genes marked by both H3K27me3 and H3K4me3. This suggests a partial reversal of AML-specific epigenetic repression and reactivation of gene expression programs associated with normal hematopoietic differentiation.

Discussion

HSPC fate is tightly regulated by transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms, and disruptions in these processes can create vulnerabilities that promote leukemic transformation. To investigate these perturbations in a disease-relevant context, we leveraged iPSCs derived from a patient with KMT2A::MLLT3-rearranged AML. iPSC models of myeloid malignancies are increasingly used for mechanistic and functional studies as they preserve the genetic background, including somatic mutations, of the original patient cells.8 Although iPSC reprogramming resets the epigenome,30,31 prior studies have shown that cancer-specific epigenetic features reemerge during hematopoietic differentiation, but not in other lineages.5 In line with this finding, our transcriptional analyses revealed high similarity between KMT2A::MLLT3 and wild-type iPSCs, with distinct profiles emerging during hematopoietic specification.5

TFs interact with specific DNA sequences to recruit epigenetic regulators, establishing chromatin states that coordinate the activation or repression of cis-regulatory elements.32-34 Disruption of this TF–epigenetic network may lead to a leukemic transcriptome that drives AML initiation and maintenance. Several AML subtype-specific TF networks have been described,35 including those associated with KMT2A-r and NPM1 mutations, which share regulatory and phenotypic characteristics.36,37 Our MARA network analysis highlighted significant motif activity for TFs shared with the NPM1-mutated AML network, including JUN, SNAI1, NKX2-3, HES1, MYC/MAX, ETS1, and BHLHB2. Collectively, we identified alterations in transcriptional programs and regulatory networks involving PRC2 targets and bivalent genes, which may contribute to AML pathogenesis.

We further identified NFYA and validated MYC15 as direct targets of KMT2A::AF9. The binding of KMT2A::AF9 correlated with an increased expression of both TFs, suggesting enhanced transcriptional activity. NFYA is required for hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and survival.38 Moreover, NFY has previously been identified as a key TF node regulating cell cycle and proliferation in AML cells with the KMT2A::MLLT3 translocation.13 Recently, NFYA was shown to recruit Menin to a subset of target genes involved in cell cycle and senescence, implicating NFYA in the genomic specificity of the Menin–UTX molecular switch in KMT2A::AF9 AML.39 In line with this notion, our analyses identified KMT2A occupancy at the NFYA promoter, with fusion binding detected in THP-1 cells and wild-type occupancy observed in patients with AML. These findings support NFYA as a KMT2A target, and the absence of a fusion-specific peak at this locus in patient data likely reflects overlap between wild-type and fusion binding. In parallel, SPI1 (PU.1), which is a key TF driving myeloid differentiation and active in THP-1 cells,13 exhibited decreased motif activity in AML-HSPCs. All these findings support a model in which KMT2A::AF9 binds the NFYA promoter and upregulates its expression to enhance proliferative programs, while reduced SPI1 activity contributes to impaired differentiation. The combined effects of NYFA activation and SPI1 repression may underlie key aspects of leukemogenic transcriptional dysregulation in KMT2A-rearranged AML. Future studies directly testing NFY complex perturbation in KMT2A-rearranged AML models will be essential to confirm its role in leukemogenesis.

Polycomb regulation plays a critical role in maintaining the balance between stem cell self-renewal and differentiation, which is essential for functional hematopoiesis.40,41 A disruption of this balance has been implicated in various hematologic malignancies, where aberrant Polycomb activity contributes to impaired differentiation and uncontrolled proliferation.42 Recently, a noncanonical function of EZH2 was described in AML, in which it promotes oncogenesis through interaction with c-Myc.43 Nonetheless, its catalytic activity remains indispensable for AML development. PRC2 members are also closely linked to the progression and maintenance of KMT2A-rearranged AML, with loss-of-function mutations further implicating their role in leukemogenesis.42-44 These findings support the notion that PRC2 activation is not merely a passive feature of the leukemic state, but rather a functionally relevant downstream consequence of the KMT2A::AF9 fusion. In agreement with this concept, EZH2 inhibitor UNC1999 specifically targeted the self-renewal capacity of KMT2A-rearranged AML, but not KMT2A wild-type AML, indicating a direct mechanistic link between KMT2A::AF9 and PRC2 activity. Experiments in mice have demonstrated that PRC2 activity is required for KMT2A::AF9 AML and that the complete loss of PRC2 function by inactivation of the essential component EED is incompatible with AML.44 In addition, treatment with UNC1999 has shown promising antileukemic effects in murine KMT2A-rearranged AML cells.29 In addition, the PRC1 member CBX8 was found to interact with KMT2A::AF9 and contribute to leukemogenesis.45 PRC not only maintains a repressed chromatin state through H3K27me3, but also regulates bivalent genes marked via both repressive H3K27me3 and activating H3K4me3 histone modifications. This dual regulation maintains the developmental and differentiation genes in a poised state, allowing rapid transition from transcriptional silencing to activation.46

Bivalent genes are frequently dysregulated in cancer, including AML, which displays enhanced DNA methylation and transcriptional repression.46,47 We demonstrate that KMT2A::AF9 downregulates bivalent genes in AML-HSPCs, specifically in genes involved in hematopoietic cell fate. In addition, AML-HSPCs exhibited disrupted epigenetic regulation and altered expression levels of PRC members, which may render them susceptible to epigenetic therapies. Consequently, treatment with UNC1999 and AZA reactivated bivalent genes in AML-HSPCs, but not control-HSPCs, reflecting the greater dependence of AML cells on PRC2-mediated repression that that of normal cells with intact epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. PRC2 and DNMT2 inhibition suppressed colony formation across all AML-HSPC lines, irrespective of co-occurring somatic mutations, indicating that the observed effects are primarily driven by the KMT2A-r.

In summary, we demonstrate that KMT2A::AF9 establishes a transcriptional network, which includes NFYA and other factors, that interacts with Polycomb members to establish a repressed transcriptional program in leukemic HSPCs. This repressive state can be reversed with epigenetic inhibitors. Our data suggest that KMT2A-rearranged AML, characterized by altered epigenetic regulation, is particularly sensitive to such inhibition compared with cells retaining intact regulatory machinery, indicating a potential therapeutic window.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark P. Chao and Ravindra Majeti for the generous gift of the induced pluripotent stem cell lines; Nikolas Herold and Ingrid Lilienthal for kindly providing the leukemia cell lines; and the MedH Flow Cytometry Core Facility, financed by the Infrastructure Board at Karolinska Institutet, for providing instruments for cell analysis.

A.L. was funded by Cancerfonden (grant no. 23 2892 Pj) and Radiumhemmets Forskningsfonder (grant no. 231273). A.P. received support from Barncancerfonden (grant no. 4-867/2023). V.L. was funded by Vetenskapsrådet/The Swedish Research Council (grant no. 2020-01902), Wenner-Gren Foundations (grant nos. WUP2020-0002 and UPD2021-0226), The Center for Innovative Medicine (CIMED; grant no. FoUI-963467), and the SFO StratRegen Strategic Research Area. A.L. and V.L. also received support from Ming Wei Lau Centre for Reparative Medicine Seed Grant Programme, Karolinska Institutet (grant no. 2-4384/2023).

In memory of Professor Ola Hermanson (1965-2025), Karolinska Institutet, a pioneer in epigenetics and a cherished colleague.

Authorship

Contribution: A.P., J.T., S.L., V.L., and A.L. designed the project; A.P., J.T., D.C.G., and S.H. performed and analyzed the experiments; A.P., A.N., A.T.-J.K., B.K., and X.Z. performed the computational analysis; E.A. supervised and advised on the analysis; and A.P., J.T., A.N., V.L., and A.L. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: BK took a position with AstraZeneca R&D, and EA took a position with GSK R&D during the submission of the manuscript. Neither AstraZeneca R&D nor GSK R&D were involved at any stage of the work presented here, and there is no conflict of interest related to either organization for this work. BK and EA may own stock options in AstraZeneca and GSK, respectively. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andreas Lennartsson, Center for Hematology and Regenerative Medicine, Department of Medicine Huddinge, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, Sweden; email: andreas.lennartsson@ki.se; and Vanessa Lundin, Center for Hematology and Regenerative Medicine, Department of Medicine Huddinge, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, Sweden; email: vanessa.lundin@ki.se.

References

Author notes

A.P., J.T., and A.N. contributed equally to this work.

V.L. and A.L. are joint last authors.

Sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession numbers GSE276955 [RNA sequencing; token, mbqbkeamnnyznwd] and GSE276959 [cap analysis of gene expression sequencing; token, wpohqgioxxohtut]).

Supplemental Table 3 summarizes all publicly available data sets used in the analyses.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![PRC2 members associate with repressed genes in AML-HSPCs. (A) Schematic of hematopoietic differentiation of control- and AML-iPSCs with days indicating time points at which samples were harvested for CAGE sequencing. (B) Heat map showing unsupervised clustering of the 100 most variable genes in control- and AML-iPSCs during hematopoietic specifications with cells harvested at the indicated time points (n = 4). (C) Heat map depicting dynamic changes in motif activity in promoters between control- and AML-iPSC differentiation as inferred from CAGE data using MARA. (D) Individual motif activity profiles of ARNT_ARNT2_BHLHB2_MAX_MYC_USF1; ETS1,2; LMO2; TFCP2; SNAI1..3; SPI1; NFY(A,B,C); and ZEB1 promoters between control and AML differentiation as inferred from CAGE data using MARA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using unpaired t test for each time point. (E) Box plots showing expression levels (log2[CPM + 1]) of MYC and NFYA from RNA-seq of control and AML cells at iPSC and HSPC stages. Boxes represent interquartile range with whiskers extending to 1.5× interquartile range and horizontal lines denoting median values. Outliers are shown as individual points. Adjusted P values (FDR) derived from DESeq2 results. (F) Heat map of unsupervised clustering of candidate ChIP-seq signatures from ChIP-Atlas, showing differential patterns between control- and AML-HSPCs across days 8, 10, and 12 of hematopoietic differentiation. (G) STRING network of TFs with differential motif activity and direct interaction to PRC1/2 members (circled in black). Nodes in the network represent proteins, and edges represent predicted associations based on various sources of evidence, which include curated databases (light blue), performed experiments (purple), text-mining (yellow), coexpression (black), and homology (dark blue). ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. ns, not significant; CPM, counts per million; FDR, false discovery rate; TPM, transcripts per million.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodneoplasia/3/1/10.1016_j.bneo.2025.100172/1/m_bneo_neo-2025-000736-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1768505263&Signature=iHX5ovv74QekKPb-isbxkQ6ii7d3hlMJvtUH89NN93GJv0NqDtZx5w52Ti2PWwEP25hMx0LEtEDLARBwdi5nFgea1cHUWmKaVXgIX2d9u~xFTQnSfGjRebr3-kGjhNw2laTSYrCNa6olc7IvEw-6OSlJXqtkkSZFR5yU2FWBfzG1AzjQL3OBVSbk4NPLhXHLHeSE4dTxfS0DWjXbHFxqp8EM1eE3xB2wMCCjrFjG09iwKniGpN9JJymepYTR5qId2iaFTDMqyOSh~zTqoDeu3wpIk~O8mnG4MdQwdFvkemNZ40Roztd6t4sn260SkAcsgczskVPtSya2-9H3Kq4-oQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)