TO THE EDITOR:

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and its ligand, CD86, are expressed within the classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) tumor microenvironment (TME) at even higher frequency than Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligands. Furthermore, CTLA-4–positive T cells have disproportionately higher expression in close proximity to CD86+ Hodgkin Reed Sternberg (HRS) cells and macrophages, suggesting that CTLA-4 signaling functions to establish an immunologically privileged niche around HRS cells and that the CTLA-4 pathway plays a key role in immune evasion.1 Monotherapy with the CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody (mAb), ipilimumab, has yielded responses in patients with cHL who relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT),2,3 but ipilimumab has not been tested as a monotherapy in the pre-alloSCT setting. Trials that combined ipilimumab with a PD-1 mAb with or without brentuximab vedotin in PD-1–naïve patients failed to demonstrate a clear benefit with the addition of ipilimumab.4,5 Together, these results suggest that ipilimumab has therapeutic potential in cHL but that combination treatment in unselected patients may not be a successful strategy. To further investigate the role of ipilimumab in cHL among PD-1–exposed patients and to identify candidate biomarkers associated with ipilimumab response, we conducted a phase 2 clinical trial (www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04938232) in which ipilimumab was tested with or without nivolumab in patients with relapsed or refractory cHL.

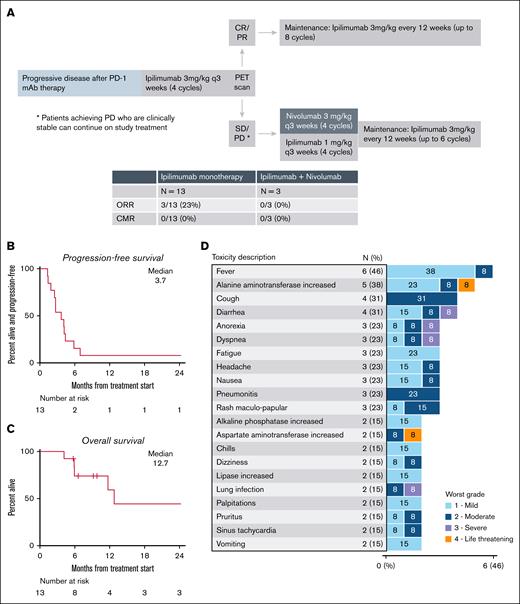

The key inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of cHL, age of ≥18 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 2, receipt of ≥2 previous therapies, and progressive disease following PD-1–based treatment. Patients with a history of alloSCT, autoimmune disease, or a grade 4 immune-related adverse event during PD-1 mAb therapy were excluded. Patients received ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 doses and then underwent restaging using positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Ipilimumab responders (complete response or partial response [PR]) then received ipilimumab maintenance (3 mg/kg every 12 weeks for up to 8 doses). Ipilimumab nonresponders (stable disease or progressive disease) who were clinically stable received 4 cycles of ipilimumab (1 mg/kg) and nivolumab (3 mg/kg), dosed every 3 weeks, followed by ipilimumab maintenance for up to 7 cycles (Figure 1A). The primary end point was best objective response rate (ORR) to ipilimumab monotherapy based on positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging that was assessed centrally using the 2014 Lugano criteria.6 Ipilimumab monotherapy would be judged as promising if ≥4 of 13 patients obtained an objective response (null hypothesis ORR, 10%; alternative hypothesis ORR, 40%; 83% power; 3.4% 1-sided type 1 error). Secondary end points included safety, progression-free survival, duration of response, and overall survival (supplemental Methods). The trial was approved by institutional review boards at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, and University of Chicago, and all patients gave written informed consent. Pretreatment biopsy samples were analyzed using multiplex immunofluorescence to define the TME features among PD-1–exposed individuals with cHL and to describe features associated with response, as previously described.7 Antibodies and targeted cell populations are detailed in the supplemental Methods.

Trial design and clinical outcomes. (A) Trial schema. (B) Progression-free survival. (C) Overall survival. (D) Adverse events for patients receiving ipilimumab monotherapy. CMR, complete metabolic response; CR, complete response.

Trial design and clinical outcomes. (A) Trial schema. (B) Progression-free survival. (C) Overall survival. (D) Adverse events for patients receiving ipilimumab monotherapy. CMR, complete metabolic response; CR, complete response.

From September 2021 to August 2023, 13 patients were enrolled. The baseline characteristics are summarized in supplemental Table 1. The median age was 39 years (range, 23-76), and the patients received a median of 4 (range, 3-15) previous therapies, including a median of 1 (range, 1-4) PD-1 mAb–based treatment. Five patients received PD-1 mAb monotherapy only, 3 received PD-1–based combinations, and 5 received both PD-1 monotherapy and 1 or more PD-1 combinations. The best ORR was 30% (3/10) for previous PD-1 monotherapy and 55% (6/11) for PD-1 combinations (supplemental Table 2). At study entry, 12 of 13 (92%) patients were PD-1 refractory, defined as achieving a best response of progressive disease during PD-1 monotherapy, a best response of progressive disease to the most recent PD-1 containing regimen, or progressive disease while on active PD-1 mAb treatment. A PD-1–based regimen directly preceded study treatment in 9 patients. Eight patients (62%) had a previous autologous SCT.

Patients received a median of 2 cycles of ipilimumab monotherapy (range, 1-4). Three patients achieved a PR (ORR, 23%) with no complete responses observed. All responses were observed in PD-1 refractory patients. Among 10 ipilimumab nonresponders, 7 discontinued the study treatment and 3 opted to receive combination treatment with nivolumab and ipilimumab on trial. Among these 3 patients, none experienced an objective response. The most common reasons for treatment discontinuation were progressive disease (n = 8), toxicity (n = 4), and patient decision (n = 1). With a median follow-up of 11.5 months, the median progression-free survival for ipilimumab monotherapy was 3.7 months (Figure 1B). Among the 3 responders, the duration of response was brief for 2 patients (3.2 and 1.5 months), whereas the other responder remained in remission 27.8 months later (although the patient achieved a PR after ipilimumab monotherapy, the patient received additional salvage therapy, followed by alloSCT). The 1-year overall survival was 59% (Figure 1C). Four patients underwent a subsequent alloSCT, and all received additional salvage treatments before transplantation.

The most common treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) with ipilimumab monotherapy are listed in Figure 1D. Grade ≥3 TRAEs with ipilimumab monotherapy occurred in 6 patients and included alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase elevation in 1 patient; abdominal pain, cytokine release syndrome, dyspnea, lung infection, and thrombocytopenia in 1 patient; urinary tract infection in 1 patient; colitis in 1 patient; diarrhea and hyponatremia in 1 patient; and anorexia in 1 patient. Four patients discontinued ipilimumab monotherapy because of TRAEs (grade 4 alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase elevation, grade 3 lung infection, grade 3 colitis, and grade 3 diarrhea). TRAEs for the 3 patients who received ipilimumab and nivolumab included 1 case each of hypothyroidism, bilateral hand rash, infusion-related reaction, and peripheral sensory neuropathy (all grade 1-2).

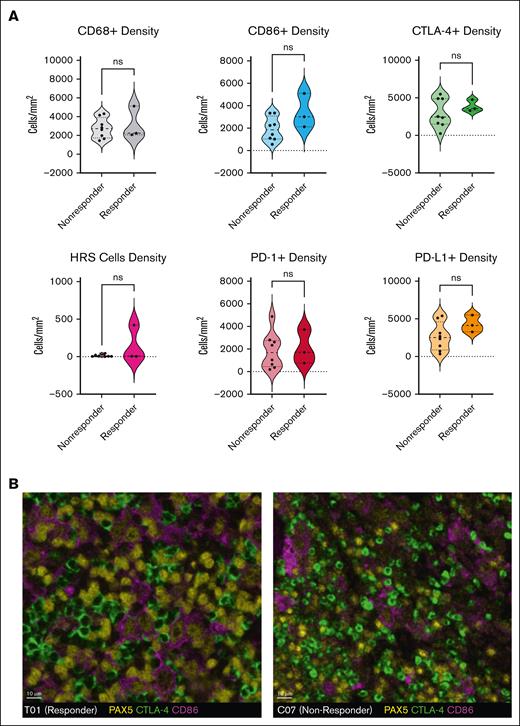

Pretreatment formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsy samples were available and sufficient for multiplex immunofluorescence testing in 11 of 13 patients (3 responders, 8 nonresponders). CTLA-4 and CD86 were expressed in all tumors, typically with each marker present on more than 10% of cells. There was a trend toward more frequent CTLA-4 expression than PD-1 expression (median: 3277 vs 1688 cells per mm2; P = .10), whereas expression of CD86 and PD-L1 were similar (median: 2243 vs 3126 cells per mm2; P = .30). The density of intratumoral macrophages (CD68) or HRS cells (PAX5[dim]) and the expression of CTLA-4, CD86, PD-1, and PD-L1 were not associated with ipilimumab response (Figure 2A-B). Limited tissue availability and quality precluded additional analyses of cell-cell interactions and spatial distribution.

Multiplex immunofluorescence analysis of pretreatment tumor biopsies. CD86 and PD-L1 are typically expressed by PAX5-positive HRS cells and CD68+ macrophages, whereas CTLA-4 and PD-1 are most commonly expressed by CD3+ T cells. (A) The densities (cells per mm2) of CD68+ macrophages, PAX5(dim)-positive HRS cells, CD86+, PD-L1–positive, CTLA-4–positive, and PD-1–positive cells were not associated with a response to ipilimumab monotherapy. (B) Multiplex immunofluorescence staining of pretreatment biopsies from patient T01 (responder, left) and C07 (nonresponder, right) shows that, in both cases, a subset of the PAX5(dim)–positive HRS cells (yellow) coexpressed CD86 (purple) and are surrounded by and in contact with CTLA-4–positive cells (green). Similar expression and distribution of CTLA-4 in responders and nonresponders suggest that they limited efficacy of ipilimumab cannot be attributed to a lack of drug target in the TME.

Multiplex immunofluorescence analysis of pretreatment tumor biopsies. CD86 and PD-L1 are typically expressed by PAX5-positive HRS cells and CD68+ macrophages, whereas CTLA-4 and PD-1 are most commonly expressed by CD3+ T cells. (A) The densities (cells per mm2) of CD68+ macrophages, PAX5(dim)-positive HRS cells, CD86+, PD-L1–positive, CTLA-4–positive, and PD-1–positive cells were not associated with a response to ipilimumab monotherapy. (B) Multiplex immunofluorescence staining of pretreatment biopsies from patient T01 (responder, left) and C07 (nonresponder, right) shows that, in both cases, a subset of the PAX5(dim)–positive HRS cells (yellow) coexpressed CD86 (purple) and are surrounded by and in contact with CTLA-4–positive cells (green). Similar expression and distribution of CTLA-4 in responders and nonresponders suggest that they limited efficacy of ipilimumab cannot be attributed to a lack of drug target in the TME.

Despite strong preclinical data that support a role for the CTLA-4 axis in cHL, we observed limited clinical activity with CTLA-4 blockade with ipilimumab in this high-risk cohort of patients with multiple relapsed and frequently PD-1 mAb-refractory cHL. In this small cohort, we could not identify factors associated with response to ipilimumab. Pretreatment biopsies demonstrated frequent expression of both CTLA-4 and its ligand, CD86, similar to what was observed in previously published studies1,8; however, neither CTLA-4 nor CD86 expression was associated with clinical response.

Our findings add to a growing number of studies that suggest that frequent expression of immune checkpoints within the cHL TME may not be sufficient to predict the efficacy of targeted immunotherapies. Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3) and T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (TIM3) are also commonly expressed in the cHL TME (although to a lesser extent than CTLA-4),1,9 but agents that target these immune checkpoints have also yielded largely disappointing results.10,11 Other immunotherapy strategies may be needed in relapsed or refractory cHL. A large, multimodal, unbiased screening study recently identified CD86 as a promising target in cHL. In preclinical studies, blocking CD86 did not impact tumor growth, but anti-CD86 chimeric antigen receptor T cells were highly effective.8 Early-phase clinical trials that tested other cellular therapy approaches have shown high response rates, suggesting that these types of immunotherapies could be effective in cHL, although response durability remains a concern.12,13 In conclusion, our results do not support further investigation of ipilimumab in cHL and suggest that a better understanding of tumor-immune interactions will be necessary to effectively target the cHL TME. Additional advances in immunotherapy for cHL may come in the form of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell or natural-killer cell therapies rather than other immune checkpoint agents.

Acknowledgments: R.W.M. acknowledges support from a Lymphoma Research Foundation Clinical Investigator Career Development Award and an American Society of Hematology Scholar Award. R.W.M., M.M., and P.A. acknowledge the support from the Harold and Virginia Lash Grant Program. P.A. and I.E.A. acknowledge support from a scholar award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Contribution: R.W.M. designed the study, performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; R.A.R. analyzed data and reviewed the manuscript; H.O. and S.R. performed research, analyzed data, and reviewed the manuscript; and J.K., E.W., K.P., H.L., M.M., I.E.A., J.R.B., J.L.C., M.S.D., D.C.F., E.D.J., C.A.J., A.I.K., O.O.O., E.M.P., C.E.R., M.A.S., P.A., J.S.A., and A.S.L. performed research and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.W.M. reports serving on an advisory board for GenMab, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), AbbVie, Ipsen, and Kite; serving as a consultant for DG Medicine; receiving honararia from GenMab and AbbVie; and receiving institutional research fundingfrom Merck, BMS, GenMab, and Genentech/Roche. J.K. reports serving on advisory boards for BMS, AbbVie, GenMab, BeiGene, ADC Therapeutics, and Gilead. I.E.A. reports receiving consulting fees from AstraZeneca, BeOne, and Lilly; receiving institutional research funding from BeOne and Lilly; and receiving honorarium from Lilly. J.R.B. reports serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Acerta/AstraZeneca, Alloplex Biotherapeutics, BeiGene, BMS, EcoR1, Galapagos NV, Genentech/Roche, Grifols Worldwide Operations, InnoCare Pharma Inc, Loxo/Lilly, Magnet Biomedicine, Merck, and Pharmacyclics; receiving research funding from BeiGene, Gilead, iOnctura, Loxo/Lilly, MEI Pharma, Nagoon Therapeutics, and TG Therapeutics; and serving on the data safety monitoring board for Grifols Therapeutics. J.L.C. reports serving as a consultant or in an advisory role for ADT Biotech, Seagen, GenMab/AbbVie, and Genentech; and receiving research funding Merck, Genentech/Roche, Bayer, AbbVie, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. M.S.D. reports receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Ascentage Pharma, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Galapagos, Genentech, GenMab, Janssen, Merck, MEI Pharma, Nuvalent, and Schrӧdinger; receiving research funding from Ascentage Pharma, MEI Pharma, and Novartis; and receiving royalties from Up-To-Date. D.C.F. reports no conflict of interest. E.D.J. reports serving on advisory boards for Ipsen, Daiichi, BMS, and Bayer; and receiving research support from Merck, Celgene, and BMS. C.A.J. reports serving as a consultant for Kite, BMS, Novartis, Miltenyi, Autolus, Appia, Aleta, Kyverna, Umoja, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, Sana, Janssen, Synthekine, Galapagos, and Caribou. A.I.K. reports receiving research funding (institutional) from AstraZeneca; and receiving honoraria from MJH Life Sciences. C.E.R. reports serving as a consultant or in an advisory role for AstraZeneca and Genentech; and receiving research institutional funding from BeiGene, Genentech, and Lilly. M.A.S. reports receiving research funding from BMS, Merck, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Genentech, and AbbVie; and serving on an advisory board for BMS and AstraZeneca. P.A. reports serving as a consultant for Merck, BMS/Celgene, GenMab, Enterome, Genentech/Roche, ATB Therapeutics, and Regeneron; and receiving research funding from Kite. Institutional Research funding from Merck, BMS/Celgene, Adaptive, Genentech, IGM, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. S.R. reports receiving research funding from BMS, KITE/Gilead, and Coherus Pharmaceuticals; and Scientific Advisory Board of Immunitas Therapeutics and iTEOS Therapeutics. J.S.A. reports serving as a consultant for AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Celgene, Foresight Diagnostics, Genentech, Gilead, Interius, Miltenyi, Novartis, Roche, and Seagen; receiving research support (to the institution) from BMS, Celgene, Cellectis, Genentech, Merck, Mustang Bio, Regeneron, Seagen, and Takeda. A.S.L. reports serving as a consultant or in an advisory role for GenMab; serving on the speakers bureau of Research to Practice; and serving as a consultant or in an advisory role for Pierre Fabre. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Reid Merryman, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; email: reid_merryman@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

R.W.M. and J.K. contributed equally to this study.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Reid W. Merryman (reid_merryman@dfci.harvard.edu).