Key Points

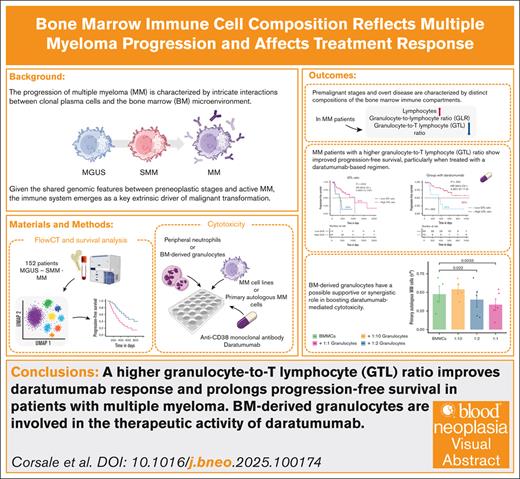

A higher GTL ratio improves daratumumab response and prolongs progression-free survival in patients with MM.

BM-derived granulocytes are involved in the therapeutic activity of daratumumab.

Visual Abstract

The progression of multiple myeloma (MM) is characterized by intricate interactions between clonal plasma cells and the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of BM immune cell composition spanning from premalignant stages to MM, using FlowCT, a semiautomated workspace empowered to analyze large data sets. Our cohort comprised 159 patients, covering monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, smoldering MM, and MM, with most undergoing treatment with a daratumumab-based regimen. The evolving disease showed alterations in immune cell populations, including a reduction in the granulocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (GLR) and granulocyte–to–T-lymphocyte (GTL) ratio, alongside an increase in T lymphocytes. Higher baseline levels of BM GLR and GTL ratio were associated with extended progression-free survival. Moreover, improved outcomes were observed in patients with a higher GTL ratio treated with daratumumab-based regimens. Furthermore, autologous BM-derived granulocytes enhance daratumumab-mediated cytotoxicity against primary autologous neoplastic plasma cells, unveiling a novel BM-granulocyte–dependent mechanism of action for daratumumab in patients with MM. These findings emphasize the dynamic nature of the BM immune compartment during MM progression and underscore the prognostic significance of immune cell composition in guiding therapeutic approaches and enhancing patient outcomes.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common hematologic malignancy defined by the presence of aberrant clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow (BM), with evidence of myeloma-defining events (MDE), and consequential organ impairment, often identified through the acronym CRAB (hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, and osteolytic bone lesions).1 In all cases, overt disease is preceded by a premalignant condition known as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), characterized by the absence of MDE and the presence of <10% of BM clonal plasma cells. MGUS can develop into MM at a rate of 1% every year.2 Lying between MGUS and MM, smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM), characterized by 10% to 59% of clonal BM plasma cells and the absence of MDE, is an intermediate asymptomatic condition with a 10-fold higher risk of progression than MGUS in the first 5 years after diagnosis.3 Guidelines recommend follow-up of these patients over time, and current progression risk models depend entirely on tumor-derived clinical laboratory data.4

Multiple genetic alterations and bidirectional interactions between clonal plasma cells and the BM milieu are required for the malignant transformation.5,6 Because the genomic landscape of preneoplastic conditions and active MM is frequently overlapping,7,8 it is necessary to define the critical factors promoting the neoplastic switch, which could be found outside of malignant cells. In this scenario, the role of the immune system has a strong impact. Indeed, the introduction of immunomodulatory drugs (eg, thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide)9 and innovative platforms (eg, chimeric antigen receptor T cells, antibody-drug conjugates, and bispecific T-cell engagers) demonstrated the clinical value of immunotherapeutic approaches as weapons for the treatment of MM.

A better understanding of this scenario may be crucial to the identification and subsequent management of patients with premalignant plasma cell dyscrasias who are at high risk of progression to improve their clinical outcomes and to identify potential targets for early therapeutic intervention.

Thus, this study aimed to map alterations in BM immune cell composition along the MGUS-MM progression. Furthermore, we correlated BM immune compartment composition with clinical behavior to identify cell types associated with improved response to therapy in patients with MM.

Methods

Patients enrolled

We collected BM aspirates from patients with MGUS (n = 43), SMM (n = 33), and newly diagnosed MM (n = 83) at Paolo Giaccone University Hospital in Palermo. Patients with MM with available progression-free survival (PFS) data (n = 78) were stratified into 2 groups according to first-line therapy; 59 patients received daratumumab combined with lenalidomide-dexamethasone, bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone, or bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone, and were assigned to the “with daratumumab” group, whereas the remaining 19 patients received lenalidomide-dexamethasone, bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone, or bortezomib-dexamethasone alone and were included in the “without daratumumab” group. Furthermore, to validate our results, this analysis integrated an external cohort comprising 44 patients with MM, recruited at Policlinico S. Maria alle Scotte in Siena, Italy.

Data collection

Baseline demographic and clinical data were collected from medical records. The following indicators were assessed: (1) demographic characteristics, including sex, age, and baseline diseases; (2) laboratory data, including leukocyte counts, hemoglobin, serum creatinine, albumin, β2-microglobulin, calcium, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum κ and λ chains, and free light chains; (3) International Staging System (ISS) stages; (4) first-line treatment; (5) receipt of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT); and (6) median PFS.

Flow cytometric analysis of BM samples

All BM samples, obtained at diagnosis and before the initiation of treatment, were collected in EDTA tubes and stained according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, using the BD OneFlow plasma cell disorders (PCD) and plasma cell screening tube (PCST; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). BD OneFlow PCD consists of single-use tubes containing the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies in an optimized dried formulation: anti-human CD38 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti-human CD28 phycoerythrin (PE), anti-human CD27 Peridinin-Chlorophyll-Protein (PerCP)-Cyanine (Cy)5.5, anti-human CD19 PE-Cy7, anti-human CD117 allophycocyanin (APC), anti-human CD81 APC-Hilite 7 (H7), anti-human CD45 BD Horizon V450, and anti-human CD138 BD Horizon V500-C antibodies. BD OneFlow PCST consists of 2 single-use tubes: PCST, which contains anti-human CD38 FITC, anti-human CD56 PE, anti-human β2-microglobulin PerCP Cy5.5, anti-human CD19 PE-Cy7, anti-human CD45 BD Horizon V450, anti-human CD138 BD Horizon V500-C; and PCST, which contains anti-human κ-APC, and anti-human λ-APC-H7 antibodies. After staining, the cells were resuspended in 400 μL stain buffer before the acquisition on the BD FACSLyric flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Dimensionality reduction, clustering, and visualization

To identify possible differences in the BM microenvironment along MM evolution, we applied FlowCT (version 1.0.0), a semiautomated workflow for the deconvolution of immunophenotypic data and objective reporting on large data sets.10 The FlowSOM and Seurat clustering approaches were used for automated clustering. The median expression of each marker on multiuniform manifold approximation and projection and Infinicyt software (Infinicyt version 2.0.6; Cytognos SL, Salamanca, Spain) were used to characterize each cluster. Additionally, data from each sample were log2-transformed with a pseudocount (+1) and normalized using z scores per column. Heat maps were generated using the pheatmap package (version 1.0.12).

Survival analysis

To assess the prognostic value of identified BM immune populations in patients with MM, we calculated the PFS of which the starting point was first-line treatment initiation. Optimal thresholds for each immune cell type to stratify patients were determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses using R package pROC (version 1.18.5), selecting cutoffs based on the Youden index. Patients were classified into “low” and “high” groups accordingly. Survival analysis was performed with the R package survival (version 3.5.8) using univariate Cox models to assess prognostic value for PFS. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted using the R package survminer (version 0.4.9), and differences tested by log-rank test. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were reported. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for age (<65 vs >65 years), sex, LDH levels, ISS stage, and ASCT status were used to evaluate independent prognostic significance.

Clinical variable stratification and immune profile analysis

Clinical laboratory variables were divided into tertiles (low, medium, and high) based on the 33rd and 66th percentiles within normal reference ranges. This allowed detection of trends in immune cell distribution within clinically normal values. Differences across tertiles were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for post hoc analysis. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method, with adjusted P values <.05 considered significant.

Cell culture

The MM cell lines RPMI-8226 and AMO-1 were grown in T75 flasks in complete medium (StableCell RPMI 1640 with stable glutamine and sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with 25 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid) buffer, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Euroclone, Milan, Italy), and 10% and 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, respectively (Dominique Dutscher, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France). Cultures were maintained within a cell concentration range of 0.3 to 1 × 10⁹ viable cells/L, with medium replenishment occurring 3 times per week.

Isolation of peripheral neutrophils and BM-derived granulocytes, and cytotoxic assay

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Ficoll-Paque Plus density gradient centrifugation (Cytiva) from buffy coats obtained from healthy blood donors (n = 5). Simultaneously, peripheral neutrophils were isolated and purified following the procedure described by Cui et al.11 Peripheral neutrophils and PBMCs were cocultured with MM cell lines AMO-1 and RPMI-8226 at effector-to-target ratios of 1:1, for 24 hours in a 96-well plate, with or without daratumumab (10 μg/mL; MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ). After coculture, cells were harvested, washed in cold stain buffer (BD Biosciences), and stained with the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: Annexin-V PE, 7-amino-actinomycin D (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), anti-human CD15 FITC (clone MMA), anti-human CD138 APC (clone MI15), and anti-human CD45 V500 (clone HI30; BD Biosciences). Subsequently, BM mononuclear cells (BMMCs) and granulocytes were isolated from BM samples of patients with newly diagnosed untreated MM (n = 5).

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Paolo Giaccone University Hospital and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (number 02/2022, codename: MMVision). All patients signed informed consent in accordance with our institutional requirements.

Results

Patient characteristics

This study included a total of 159 patients; 43 with MGUS, 33 with SMM, and 83 with MM. At the time of diagnosis, the mean age was 71 years for patients with MM (range, 48-91), 68 years for patients with MGUS (range, 35-87) and 75 years for patients with SMM (range, 54-92). Compared with patients with MGUS and those with SMM, patients with MM demonstrated significantly lower hemoglobin (P < .001) and albumin levels (P < .01) but increased β2-microglobulin levels (P < .001). Additionally, patients with MGUS exhibited higher neutrophil counts (P < .05). The baseline demographic and clinical data of the 3 cohorts are summarized in Table 1. Regarding the external cohort of 44 patients with MM, the mean age was 69 years (range, 43-88) and clinical data are summarized in supplemental Figure 6E.

Clinical characteristics of enrolled patients at the time of diagnosis

| Characteristic . | MGUS∗ . | SMM∗ . | MM∗ . | P value† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 43 | 33 | 83 | |

| Age, y | 68 (35-87) | 75 (54-92) | 71 (48-91) | .3 |

| Sex, male/female | 26/17 | 13/20 | 39/44 | .2 |

| WBC | 12 033 (3640-133 200) | 6691 (4050-11 220) | 6994 (2200-23 890) | .054 |

| Neutrophils, cells per μL | 5548 (1250-10 700) | 3958 (2010-7880) | 4495 (210-20 740) | .025 |

| Lymphocytes, cells per μL | 1861 (410-4620) | 1991 (1070-2890) | 1754 (320-4130) | .070 |

| Monocytes, cells per μL | 567 (230-1210) | 566 (270-2330) | 583 (40-2060) | .7 |

| Platelets, cells per μL | 241 484 (105 000-455 000) | 240 545 (121 000-439 000) | 242 096 (52 000-642 000) | > .9 |

| Hb, g/dL | 12.39 (7.40-16.60) | 12.53 (7.80-15.90) | 10.96 (6.20-17.00) | < .001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.52 (0.61-5.07) | 1.12 (0.60-4.69) | 1.66 (0.54-8.19) | .059 |

| Albumin, g/L | 41.0 (28.0-47.0) | 39.5 (26.0-48.0) | 36 (3-51.0) | .002 |

| β2-microglobulin, mg/dL | 4.9 (1.1-41.6) | 4.2 (1.5-19.8) | 7.7 (1.7-38.4) | < .001 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 9.30 (7.40-10.20) | 9.41 (8.40-10.40) | 9.53 (7.60-14.44) | .2 |

| LDH, U/L | 179 (91-264) | 158 (79-270) | 178 (77-484) | .7 |

| Serum κ chain, g/L | 3.4 (0.9-6.6) | 5.6 (0.6-14.9) | 5.5 (0.3-24.4) | .8 |

| Serum λ chain, g/L | 1.6 (0.5-3.1) | 2.4 (0.3-11.5) | 4 (0.1-38) | .7 |

| κ-FLC, mg/L | 62 (9-308) | 339 (8-5960) | 385 (1-8930) | >.9 |

| λ-FLC, mg/L | 49 (9-183) | 104 (2-599) | 594 (2-12 000) | .5 |

| rFLC, g/L | 2 (0-6) | 34 (0-773) | 46 (0-1094) | >.9 |

| ISS | ||||

| I | 25 | |||

| II | 24 | |||

| III | 34 | |||

| ASCT | ||||

| Yes | 28 | |||

| No | 55 | |||

| Therapy | ||||

| Daratumumab + RD | 26 | |||

| Daratumumab + VMP | 10 | |||

| Daratumumab + VTd | 26 | |||

| RD | 7 | |||

| Vd | 2 | |||

| VTd | 12 |

| Characteristic . | MGUS∗ . | SMM∗ . | MM∗ . | P value† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 43 | 33 | 83 | |

| Age, y | 68 (35-87) | 75 (54-92) | 71 (48-91) | .3 |

| Sex, male/female | 26/17 | 13/20 | 39/44 | .2 |

| WBC | 12 033 (3640-133 200) | 6691 (4050-11 220) | 6994 (2200-23 890) | .054 |

| Neutrophils, cells per μL | 5548 (1250-10 700) | 3958 (2010-7880) | 4495 (210-20 740) | .025 |

| Lymphocytes, cells per μL | 1861 (410-4620) | 1991 (1070-2890) | 1754 (320-4130) | .070 |

| Monocytes, cells per μL | 567 (230-1210) | 566 (270-2330) | 583 (40-2060) | .7 |

| Platelets, cells per μL | 241 484 (105 000-455 000) | 240 545 (121 000-439 000) | 242 096 (52 000-642 000) | > .9 |

| Hb, g/dL | 12.39 (7.40-16.60) | 12.53 (7.80-15.90) | 10.96 (6.20-17.00) | < .001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.52 (0.61-5.07) | 1.12 (0.60-4.69) | 1.66 (0.54-8.19) | .059 |

| Albumin, g/L | 41.0 (28.0-47.0) | 39.5 (26.0-48.0) | 36 (3-51.0) | .002 |

| β2-microglobulin, mg/dL | 4.9 (1.1-41.6) | 4.2 (1.5-19.8) | 7.7 (1.7-38.4) | < .001 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 9.30 (7.40-10.20) | 9.41 (8.40-10.40) | 9.53 (7.60-14.44) | .2 |

| LDH, U/L | 179 (91-264) | 158 (79-270) | 178 (77-484) | .7 |

| Serum κ chain, g/L | 3.4 (0.9-6.6) | 5.6 (0.6-14.9) | 5.5 (0.3-24.4) | .8 |

| Serum λ chain, g/L | 1.6 (0.5-3.1) | 2.4 (0.3-11.5) | 4 (0.1-38) | .7 |

| κ-FLC, mg/L | 62 (9-308) | 339 (8-5960) | 385 (1-8930) | >.9 |

| λ-FLC, mg/L | 49 (9-183) | 104 (2-599) | 594 (2-12 000) | .5 |

| rFLC, g/L | 2 (0-6) | 34 (0-773) | 46 (0-1094) | >.9 |

| ISS | ||||

| I | 25 | |||

| II | 24 | |||

| III | 34 | |||

| ASCT | ||||

| Yes | 28 | |||

| No | 55 | |||

| Therapy | ||||

| Daratumumab + RD | 26 | |||

| Daratumumab + VMP | 10 | |||

| Daratumumab + VTd | 26 | |||

| RD | 7 | |||

| Vd | 2 | |||

| VTd | 12 |

The boldface values in Table 1 indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups, as intended.

FLC, free light chain; Hb, hemoglobin; max, maximum; min, minimum; RD, lenalidomide-dexamethasone; rFLC, free light chain ratio; Vd, bortezomib-dexamethasone; VMP, bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone; VTd, bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone; WBC, white blood cell.

Mean (min-max); n (%).

Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test; Pearson χ2 test; Fisher exact test.

FlowCT analysis reveals quantitative alterations in the BM milieu along MM progression

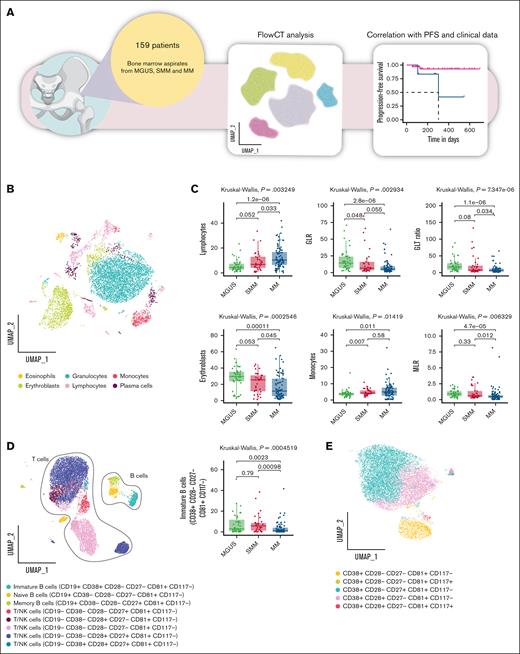

Plasma cells and BM microenvironment composition were assessed in premalignant plasma cell dyscrasias and active MM using FlowCT (Figure 1A). Clusters for the PCD tube were identified and annotated by visualizing marker expression levels on manifold approximation and projection (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 1A). The abundance of each identified population was then compared across the different disease groups (MGUS, SMM, and MM).

FlowCT analysis of BD OneFlow PCD tube. (A) The scheme illustrates the experimental design. (B) UMAP of eosinophils (CD45+bright, SCChigh), erythroblasts (CD45−, CD38−, SCClow), granulocytes (CD45+dim, SCChigh), lymphocytes (CD45+, SCClow), monocytes (CD45+, SCCint), and plasma cells (CD138+ CD38+high) identified by self-organizing map (SOM) of BD OneFlow PCD tube. (C) Box plots show a statistically different distribution of lymphocytes, GLR, GTL ratio, erythroblasts, monocytes, and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) as MM progresses. (D) Subclustering of lymphocyte subsets based on the median expression of the individual marker in each cell cluster. Box plots represent the proportion of immature B cells (CD38+ CD28− CD27− CD81+, CD117−) between patients with MGUS, SMM, and MM. (E) Subclustering of monocytes cell subsets based on the median expression of the individual marker in each cell cluster. UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

FlowCT analysis of BD OneFlow PCD tube. (A) The scheme illustrates the experimental design. (B) UMAP of eosinophils (CD45+bright, SCChigh), erythroblasts (CD45−, CD38−, SCClow), granulocytes (CD45+dim, SCChigh), lymphocytes (CD45+, SCClow), monocytes (CD45+, SCCint), and plasma cells (CD138+ CD38+high) identified by self-organizing map (SOM) of BD OneFlow PCD tube. (C) Box plots show a statistically different distribution of lymphocytes, GLR, GTL ratio, erythroblasts, monocytes, and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) as MM progresses. (D) Subclustering of lymphocyte subsets based on the median expression of the individual marker in each cell cluster. Box plots represent the proportion of immature B cells (CD38+ CD28− CD27− CD81+, CD117−) between patients with MGUS, SMM, and MM. (E) Subclustering of monocytes cell subsets based on the median expression of the individual marker in each cell cluster. UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

We observed a significant reduction in the granulocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (GLR; median: 14.21 in MGUS, 6.72 in SMM, and 4.98 in MM) and granulocyte-to–T-lymphocyte (GTL) ratio (median: 16.83 in MGUS, 7.37 in SMM, and 5.30 in MM), erythroblast frequency (median: 29.69% in MGUS, 25.45% in SMM, and 11.70% in MM), and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (median: 0.89 in MGUS, 0.61 in SMM, and 0.47 in MM) across disease stages. In parallel, lymphocyte (median: 4.31% in MGUS, 6.81% in SMM, and 10.25% in MM) and monocyte (median: 3.70% in MGUS, 4.30% in SMM, and 4.96% in MM) frequencies showed a progressive increase (Figure 1C). Additionally, eosinophil levels were reduced in patients with MM compared with those with SMM (median: 0.98% in MGUS, 1.34% in SMM, and 1.01% in MM); however, no significant differences were observed between patients with MGUS and those with SMM (supplemental Figure 1B).

Subclustering of the lymphocyte populations allowed us to identify 3 subsets of B lymphocytes (CD45+, SCClow, CD19+): naïve, identified as CD38−, CD28−, CD27−, CD81+, CD117−; memory identified as CD38−, CD28−, CD27+, CD81+, CD117−; and immature population identified as CD38+, CD28−, CD27−, CD81+, CD117−. The proportion of immature B lymphocytes differed significantly across disease stages, showing a predominant presence in MGUS and SMM, followed by a marked reduction in MM (median, 2.95% MGUS vs 5.75% SMM vs 1.01% MM; Figure 1D). Moreover, we identify 5 subsets of T lymphocytes/natural killer (NK) cells (CD45+, SCClow, CD19−, CD38−/+, CD28−/+, CD27−/+, CD81+, CD117−; Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 2A-C). Although classic lineage markers were absent, CD27 and CD28 enabled partial assessment of T-cell differentiation, distinguishing naïve/early memory (CD27+CD28+) from more differentiated or senescent cells (CD27− and/or CD28−). No significant differences were observed among the remaining cell populations across the disease stages (supplemental Figure 2B).

Contextually, we focused on monocyte cell subsets, identifying 5 populations (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 2D-F). We identified 12 different populations of plasma cells, whose overall percentage was higher in patients with SMM and those with MM (supplemental Figure 1B), among which neoplastic plasma cells were identified by gating CD138+ CD38+high cells that express aberrantly specific markers (CD19, CD45, CD27, CD81, or CD117). As expected,12,13 CD45+ CD19+/− plasma cells were more abundant in early asymptomatic condition (MGUS) than in smoldering/symptomatic disease (supplemental Figure 3A-C).

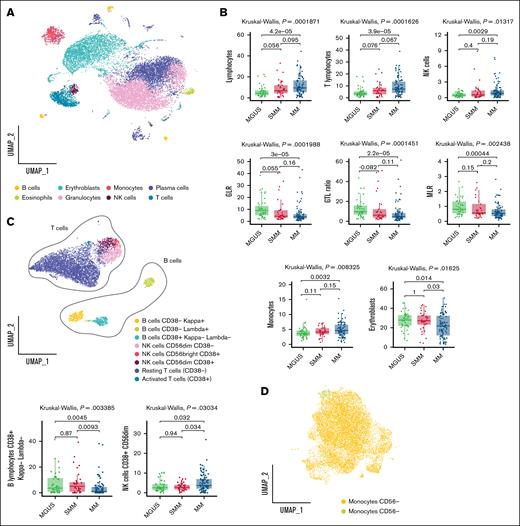

Next, we applied a similar workflow to the PCST tube (supplemental Figure 1; Figure 2A). This analysis confirmed a progressive increase in lymphocytes (median, 4.29% MGUS vs 6.82% SMM vs 9.48% MM), with a particularly notable rise in T lymphocytes (median, 3.36% MGUS vs 5.97% SMM vs 7.32% MM). NK cells and monocytes showed a modest yet significant increase in MM compared with MGUS (NK cells: 0.42% in MGUS, 0.53% in SMM, and 0.83% in MM; monocytes: 3.61% in MGUS, 4.15% in SMM, and 4.66% in MM), whereas no significant differences were found between MM and SMM.

FlowCT analysis of BD OneFlow PCST tube. (A) UMAP of eosinophils (CD45+bright, SCChigh), erythroblasts (CD45−, CD38−, SCClow), granulocytes (CD45+dim, SCChigh), T lymphocytes (CD19−, CD45+, CD56−, CD38−/+, SCClow), B lymphocytes (CD19+, CD45+, SCClow), NK cells (CD19−, CD45+, CD56+dim/+bright, SCClow), and plasma cells (CD138+ CD38+high) identified by SOM of BD OneFlow PCST tube. (B) Box plots show the statistically different distribution of lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, NK cells, GLR, GTL ratio, MLR, monocytes, and erythroblasts as MM progresses. (C) Subclustering of lymphocyte subsets based on the median expression of the individual marker in each cell cluster. Box plots represent the proportion of NK cells CD38+ CD56dim and B lymphocytes CD38+ κ− γ− between patients with MGUS, SMM, and MM. (D) Subclustering of monocyte subsets based on the median expression of the individual marker in each cell cluster. UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

FlowCT analysis of BD OneFlow PCST tube. (A) UMAP of eosinophils (CD45+bright, SCChigh), erythroblasts (CD45−, CD38−, SCClow), granulocytes (CD45+dim, SCChigh), T lymphocytes (CD19−, CD45+, CD56−, CD38−/+, SCClow), B lymphocytes (CD19+, CD45+, SCClow), NK cells (CD19−, CD45+, CD56+dim/+bright, SCClow), and plasma cells (CD138+ CD38+high) identified by SOM of BD OneFlow PCST tube. (B) Box plots show the statistically different distribution of lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, NK cells, GLR, GTL ratio, MLR, monocytes, and erythroblasts as MM progresses. (C) Subclustering of lymphocyte subsets based on the median expression of the individual marker in each cell cluster. Box plots represent the proportion of NK cells CD38+ CD56dim and B lymphocytes CD38+ κ− γ− between patients with MGUS, SMM, and MM. (D) Subclustering of monocyte subsets based on the median expression of the individual marker in each cell cluster. UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Moreover, was observed a reduction in the GLR (median, 8.91 MGUS vs 4.33 SMM vs 3.77 MM) and GTL ratio (median, 9.78 MGUS vs 6.15 SMM vs 4.89 MM), in the monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (median, 0.81 MGUS vs 0.56 SMM vs 0.53 MM), and in erythroblasts (median, 26.91% MGUS vs 25.79% SMM vs 16.67% MM) along MM evolution.

As previously, to further characterize the immune landscape across disease stages, we performed a detailed subclustering analysis of major lymphocyte populations (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 4A-C). Subclustering revealed distinct NK cell subsets, including 2 activated populations (CD38+ CD56bright and CD38+ CD56dim), and a nonactivated cytotoxic subset (CD38− CD56dim). A modest yet statistically significant increase in the frequency of the activated cytotoxic NK cell subset was observed in patients with MM compared with MGUS and SMM (median, 2.60% MGUS vs 2.75% SMM vs 3.69% MM; Figure 2C).

Among B lymphocytes, we distinguished 2 subsets of immature or activated cells based on CD38 expression and immunoglobulin light chain status (κ and λ). Notably, immature B lymphocytes exhibiting double-negative light chain immunophenotypes were significantly reduced in patients with MM compared with those with MGUS and SMM, whereas no significant differences were observed between MGUS and SMM (median, 3.63% MGUS vs 5% SMM vs 1.04% MM; Figure 2C). Additionally, 2 subsets of T lymphocytes were identified, differing by the presence or absence of the activation marker CD38, indicating activated vs resting states, respectively (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 4A-C).

Furthermore, based on CD56 expression, we discerned 2 subsets of monocytes (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 4D-F). The subclustering of plasma cell populations allowed us to identify 11 subsets of plasma cells and their clonal nature was confirmed by the restricted expression of cytoplasmic κ or λ light chains (supplemental Figure 3D-F).

In addition, we observed a consistent increase in interindividual variability within the MM group across most populations, indicating a greater degree of immune and BM microenvironment heterogeneity in advanced disease stages. Collectively, these findings suggest that premalignant stages and overt disease are characterized by distinct compositions of the BM immune compartments.

Immune cell subsets correlate with ISS and laboratory data

We evaluated the correlation between BM immune cell subsets and the ISS stages I, II, and III in patients with MM, uncovering significant immunological differences linked to disease severity (supplemental Figure 5A). Specifically, total B lymphocytes showed a significant decrease across ISS stages, with a marked reduction in stage III compared with stage II (P = .016). Naïve B lymphocytes were also significantly altered, with lower levels in stage III relative to stage II (P = .0032). Similarly, CD38− κ+ B lymphocytes exhibited a significant difference across ISS stages, showing a significant reduction in stage III compared with stage II (P = .013).

Overall, these results indicate a possible trend toward changes in immune cell composition within the BM microenvironment during disease progression, as reflected by differences observed in selected subsets.

Furthermore, we examined the correlation between BM immune cell subsets and various laboratory parameters, including calcium, creatinine, LDH, hemoglobin, albumin, and β2-microglobulin. To evaluate immunological variation, clinical variables were stratified into tertiles (low, medium, and high) based on the 33rd and 66th percentiles of their distribution within the physiological range (supplemental Figure 5B).

Among T/NK cells, the frequency of CD38+ CD28+ CD27+ CD81+ CD117− cells was reduced in individuals in the high creatinine tertile, similarly, CD38+ CD28−/+ CD27− CD81+ CD117−/+ monocytes were decreased. A comparable pattern was observed for calcium, with a reduction in CD38+ CD28+ CD27− CD81+ CD117− monocytes in the medium and high tertiles. Conversely, the frequency of CD117+ monocytes increased with higher creatinine levels.

Medium albumin levels were associated with an increased frequency of resting (CD38−) T lymphocytes and eosinophils, whereas T/NK cells CD38− CD28− CD27− CD81+ CD117− were reduced. Hemoglobin was positively associated with both eosinophil and B-cell frequencies, similarly to β2-microglobulin levels.

Among all parameters, LDH levels were strongly associated with changes in T/NK cell composition, underscoring the responsiveness of this compartment to metabolic variation within normal limits, with CD117− and CD117+ subsets enriched in the high-LDH group. Finally, eosinophils and B lymphocytes peaked in the medium LDH tertile, followed by a decline in the high group.

High GLR and GTL ratios predict improved PFS in patients with MM

We assessed the impact of BM immune cell populations on PFS among patients with MM (n = 78). Using ROC curve analysis, we identified optimal cutoff values for immune cell ratios that effectively discriminated patients based on PFS. Both the BM GLR and GTL ratio emerged as significant prognostic markers. Specifically, patients with a high BM GLR ratio (>1.98) showed a 1-year PFS rate of 80%, compared with 50% in those with a lower GLR ratio (<1.98) (log-rank P < .01; Figure 3A). This association was not observed for the peripheral blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (supplemental Figure 6A). Similarly, patients with a higher BM GTL ratio (>2.32) exhibited a 1-year PFS rate of 80%, vs 52% in those with a lower GTL ratio (<2.32; log-rank P < .01; Figure 3C). Univariate Cox regression analyses further supported these findings, confirming that both high GLR and GTL ratios were significantly associated with prolonged PFS.

PFS is dependent on BM immune cell composition. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot shows PFS according to high vs low GLR (1-year PFS rate, 80% vs 50%, respectively; (hazard ration [HR], 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.12-0.65); log-rank test, P < .01). ROC curve is used to determine the optimal GLR cutoff for predicting disease progression. The AUC was 0.649 (95% CI, 0.493-0.806). (B) Forest plot shows the results of multivariate Cox regression analysis including GLR, age (<65 vs >65 years), sex, ISS, LDH levels, and ASCT. (C) Kaplan-Meier plot shows PFS according to high vs low GTL ratio (1-year PFS rate, 80% vs 52%, respectively; HR, 0.29 [95% CI, 0.12-0.67]; log-rank test, P < .01) for patients with MM. ROC curve is used to determine the optimal GTL ratio cutoff for predicting disease progression. The AUC was 0.645 (95% CI, 0.489-0.802). (D) Forest plot shows the results of multivariate Cox regression analysis including GTL ratio, age (<65 vs >65 years), sex, ISS, LDH levels, and ASCT. (E) Patients with MM were divided into 2 groups according to the first-line treatment that they received: those who received daratumumab and those who did not. (F-G) Kaplan-Meier plots show PFS according to high vs low GTL ratio and the first-line therapy regimen, both in the daratumumab-treated group (F) (1-year PFS rate: low ratio/with daratumumab, 45%; high ratio/with daratumumab, 82%; HR, 4.26 [95% CI, 1.57-11.5]; log-rank test, P < .01) and daratumumab-untreated group (G) (1-year PFS rate: low ratio/without daratumumab, 77%; high ratio/without daratumumab, 67%; HR, 2.78 [95% CI, 0.50-15.5]; log-rank test, ns). All graphs depict results derived from PCST tube samples. AUC, area under the curve; ns, not significant; RD, lenalidomide-dexamethasone; VMP, bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone; VTd bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone.

PFS is dependent on BM immune cell composition. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot shows PFS according to high vs low GLR (1-year PFS rate, 80% vs 50%, respectively; (hazard ration [HR], 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.12-0.65); log-rank test, P < .01). ROC curve is used to determine the optimal GLR cutoff for predicting disease progression. The AUC was 0.649 (95% CI, 0.493-0.806). (B) Forest plot shows the results of multivariate Cox regression analysis including GLR, age (<65 vs >65 years), sex, ISS, LDH levels, and ASCT. (C) Kaplan-Meier plot shows PFS according to high vs low GTL ratio (1-year PFS rate, 80% vs 52%, respectively; HR, 0.29 [95% CI, 0.12-0.67]; log-rank test, P < .01) for patients with MM. ROC curve is used to determine the optimal GTL ratio cutoff for predicting disease progression. The AUC was 0.645 (95% CI, 0.489-0.802). (D) Forest plot shows the results of multivariate Cox regression analysis including GTL ratio, age (<65 vs >65 years), sex, ISS, LDH levels, and ASCT. (E) Patients with MM were divided into 2 groups according to the first-line treatment that they received: those who received daratumumab and those who did not. (F-G) Kaplan-Meier plots show PFS according to high vs low GTL ratio and the first-line therapy regimen, both in the daratumumab-treated group (F) (1-year PFS rate: low ratio/with daratumumab, 45%; high ratio/with daratumumab, 82%; HR, 4.26 [95% CI, 1.57-11.5]; log-rank test, P < .01) and daratumumab-untreated group (G) (1-year PFS rate: low ratio/without daratumumab, 77%; high ratio/without daratumumab, 67%; HR, 2.78 [95% CI, 0.50-15.5]; log-rank test, ns). All graphs depict results derived from PCST tube samples. AUC, area under the curve; ns, not significant; RD, lenalidomide-dexamethasone; VMP, bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone; VTd bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone.

Notably, both associations remained statistically significant in multivariate models adjusted for age, sex, LDH levels, ISS, and ASCT status (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.33 for GLR and 0.35 for GTL ratio), confirming their role as independent predictors of improved PFS (Figure 3B,D). These results from the PCST tube analysis were consistently replicated in the PCD tube, confirming their robustness (supplemental Figure 6B-D). Together, these results indicate that the BM GLR and GTL ratio represent independent predictors of improved PFS and may serve as valuable biomarkers for risk stratification in MM.

Subsequently, we investigated whether a different immune BM compartment at baseline could affect the response to different treatment schedules. Patients with MM were stratified into 2 groups based on the administration of anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab (Figure 3E). Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that, among patients treated with daratumumab, those with a higher BM GTL ratio experienced significantly longer PFS (log-rank P < .01), with a 1-year PFS rate of 82% compared with 45% in the low–GTL ratio group. In contrast, no statistically significant association was observed between GTL ratio and PFS in patients who did not receive daratumumab (log-rank P > .05). Supporting these results, univariate Cox regression analysis confirmed that a high GTL ratio was a significant prognostic predictor of prolonged PFS in the daratumumab-treated group but not in the untreated cohort (Figure 3F-G). These findings were further validated in another cohort of patients (supplemental Figure 6E-F).

Together these results suggest that the GTL ratio may have a predictive value in identifying patients with MM who are more likely to benefit from daratumumab-based therapy.

Daratumumab-mediated cytotoxicity is enhanced by BM-derived granulocytes

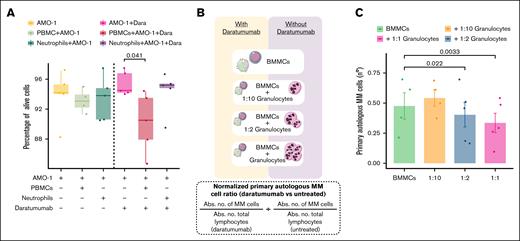

To further elucidate the cellular mechanisms driving this therapeutic response, we investigated the role of the myeloid compartment in inducing daratumumab-dependent cytotoxicity. Consistent with our PFS data, peripheral blood neutrophils exhibited negligible cytotoxicity against AMO-1 MM cell line in the presence of daratumumab, in contrast to PBMCs (Figure 4A). Similar findings were observed with the RPMI-8226 MM cell line (supplemental Figure 6G).

Granulocytes derived from the BM potentiate the cytotoxicity mediated by Dara. (A) Box plots depict the percentage of viable MM cells (7-amino-actinomycin D negative and Annexin-V negative) from the AMO-1 MM cell line after coculture with peripheral blood neutrophils and PBMCs in the presence of Dara. (B) Schematic diagram of the experimental setup for assessing cytotoxicity mediated by autologous BM-derived granulocytes. (C) Box plot showed the differences in the number of primary autologous MM cells after coculture with BM-derived granulocytes and BMMCs from patients with MM. Primary autologous MM cell counts were normalized by comparing the absolute number of viable MM cells in Dara-treated vs untreated conditions. Abs. no., absolute number; Dara, daratumumab.

Granulocytes derived from the BM potentiate the cytotoxicity mediated by Dara. (A) Box plots depict the percentage of viable MM cells (7-amino-actinomycin D negative and Annexin-V negative) from the AMO-1 MM cell line after coculture with peripheral blood neutrophils and PBMCs in the presence of Dara. (B) Schematic diagram of the experimental setup for assessing cytotoxicity mediated by autologous BM-derived granulocytes. (C) Box plot showed the differences in the number of primary autologous MM cells after coculture with BM-derived granulocytes and BMMCs from patients with MM. Primary autologous MM cell counts were normalized by comparing the absolute number of viable MM cells in Dara-treated vs untreated conditions. Abs. no., absolute number; Dara, daratumumab.

These insights prompted us to assess the involvement of autologous BM-derived granulocytes in mediating the observed therapeutic efficacy. Specifically, in the presence of daratumumab, increasing the proportion of autologous BM-derived granulocytes, particularly by restoring the original BM granulocyte-to-MM cell ratio (1:1), led to a notable reduction in primary autologous MM cell numbers (Figure 4B-C). These results suggest a possible supportive or synergistic role of BM granulocytes in boosting daratumumab-mediated cytotoxicity.

Discussion

MM is still an incurable disease, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding of the BM microenvironment's role in its development and progression.14,15 Recognizing the impact of the BM microenvironment, early intervention emerges as an appealing treatment option.16 Here, by using FlowCT, a semiautomated workflow for deconvolution of immunophenotypic data and objective reporting on large data sets,10 we described that the composition of BM immune populations varies significantly between premalignant stages and active MM. This approach enhances risk stratification by capturing immunological alterations that may not be detectable through standard clinical parameters and supports the concept of progressive immune remodeling throughout disease evolution.

During the transition to active MM, we observed a relative increase in lymphocyte populations, especially T and NK cells, which led to a decrease in the GLR and GLT ratio. Our findings are confirmed by several single-cell RNA-sequencing analyses in which the transition from the precursor stages to MM is associated with a significant expansion of T-cell populations in the BM.17-19

Delving into the influence of these immune cell populations on MM patient outcome, we report here that an elevated GLR and GTL ratio correlate with an improved PFS. In accordance with our findings, in the study of Danziger et al, the adverse outcome of patients with MM was correlated with reduced granulocyte proportions in the BM.20 Additionally, in a recent finding, an increased probability to achieve undetectable MRD, in a machine learning model, has been related to an increased presence of BM granulocytes.21

Conversely, the NLR has demonstrated contrasting results in patients with MM.22 Although we, and others, were unable to find any significant association with patients’ prognosis, several studies consistently showed that a high NLR is linked to reduced overall survival or PFS in patients with MM.23-29 Notably, we highlight that the influence of these pretreatment immune patterns on patient outcome is particularly pronounced in those undergoing a daratumumab-based regimen. Consistently, the absence of a significant association between GTL ratio and PFS in patients not receiving daratumumab supports the interpretation that GTL ratio is not a general prognostic marker but may instead reflect immune features selectively influencing response to anti-CD38 therapy. Antibodies targeting CD38, such as daratumumab, eradicate tumor cells through various mechanisms, including antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis, complement-dependent cytotoxicity, direct induction of apoptosis, enzymatic inhibition, and immunomodulation.30 NK cells have been demonstrated to be crucial in daratumumab's anti-MM activity and their CD38 expression is essential for its induced immune modulation, leading also to monocyte activation and polarization.31-34 Here, we substantially enhance the comprehension of daratumumab’s anti-MM activity by introducing a novel mechanism mediated by BM-derived granulocytes. Specifically, in our coculture system, autologous BM-derived granulocytes were associated with enhanced daratumumab-mediated cytotoxicity against primary autologous neoplastic plasma cells, leading to a significant increase in the antitumor activity compared with BMMCs alone.

Nevertheless, several aspects require careful consideration. It is crucial to highlight that a constraint in our study lies in the lack of a cohort that includes healthy individuals. Indeed, previous studies have shown that the alterations in the BM immune compartment were also observed in patients with MGUS compared with healthy individuals, suggesting that these alterations originate early in carcinogenesis during premalignancy.18,35 Additionally, delving into the functional aspects and interactions of the identified immune cell subsets could contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of their roles in the progression of MM and the response to treatment. Our findings also support the potential of the GTL ratio as a predictive marker of response to therapy; however, we acknowledge that proposing GTL ratio as a predictive surrogate requires rigorous validation in larger, well-characterized cohorts to confirm its clinical utility.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participating patients.

This work was supported by grants from the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) within the My First AIRC Grant 2020 (no. 24534, 2021/2025), Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) 2022 (no. 2022ZKKWLW and no. 20229JM25N), PRIN National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) 2022 (P2022E2JSK), and by the European Union, Next Generation EU (PNRR 2022 M6C2.I2.1) grant no. PNRR-MAD-2022-12376660.

In addition, this work was supported by the European Commission Mission Cancer grant no. 101097094 (ELMUMY) and by the PNRR – Missione 4 “Istruzione e Ricerca” – Componente 2 – Investimento 1.5 – Sicilian MicronanoTech Research And Innovation Center – SAMOTHRACE – Spoke 1 – WP4, ECS00000022 – CUP B63C22000900006, also funded by the European Union – Next Generation EU.

Authorship

Contribution: A.M.C. and C.B. conceptualized the study; A.M.C. and F.G. conducted the experiments; A.M.C. prepared the figures; A.M.C., M.S.A., E.G., M.D.S., P.P., F.C., E.B., D.R., A.G., A.S., P.T., A.B., M. Speciale, G.C., M. Sciortino, C.A., F. Brucato, M.C., R.Z., F.G., M.B., F. Buffa, N.C., F.D., S.M., S.S., and C.B. reviewed and provided critical feedback on the manuscript; and all authors contributed to the manuscript drafting and revision process, and have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Cirino Botta, Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, University of Palermo, Via del Vespro 129, 90127 Palermo, Italy; email: cirino.botta@unipa.it; and Anna Maria Corsale, Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, University of Palermo, Via del Vespro 129, N/A 90127 Palermo, Italy; email: annamaria.corsale@unipa.it.

References

Author notes

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors, Cirino Botta (cirino.botta@unipa.it) and Anna Maria Corsale (annamaria.corsale@unipa.it), on reasonable request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![PFS is dependent on BM immune cell composition. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot shows PFS according to high vs low GLR (1-year PFS rate, 80% vs 50%, respectively; (hazard ration [HR], 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.12-0.65); log-rank test, P < .01). ROC curve is used to determine the optimal GLR cutoff for predicting disease progression. The AUC was 0.649 (95% CI, 0.493-0.806). (B) Forest plot shows the results of multivariate Cox regression analysis including GLR, age (<65 vs >65 years), sex, ISS, LDH levels, and ASCT. (C) Kaplan-Meier plot shows PFS according to high vs low GTL ratio (1-year PFS rate, 80% vs 52%, respectively; HR, 0.29 [95% CI, 0.12-0.67]; log-rank test, P < .01) for patients with MM. ROC curve is used to determine the optimal GTL ratio cutoff for predicting disease progression. The AUC was 0.645 (95% CI, 0.489-0.802). (D) Forest plot shows the results of multivariate Cox regression analysis including GTL ratio, age (<65 vs >65 years), sex, ISS, LDH levels, and ASCT. (E) Patients with MM were divided into 2 groups according to the first-line treatment that they received: those who received daratumumab and those who did not. (F-G) Kaplan-Meier plots show PFS according to high vs low GTL ratio and the first-line therapy regimen, both in the daratumumab-treated group (F) (1-year PFS rate: low ratio/with daratumumab, 45%; high ratio/with daratumumab, 82%; HR, 4.26 [95% CI, 1.57-11.5]; log-rank test, P < .01) and daratumumab-untreated group (G) (1-year PFS rate: low ratio/without daratumumab, 77%; high ratio/without daratumumab, 67%; HR, 2.78 [95% CI, 0.50-15.5]; log-rank test, ns). All graphs depict results derived from PCST tube samples. AUC, area under the curve; ns, not significant; RD, lenalidomide-dexamethasone; VMP, bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone; VTd bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodneoplasia/3/1/10.1016_j.bneo.2025.100174/1/m_bneo_neo-2025-000665-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1768498440&Signature=tx6tllluIE4tRkZokgfGlIPlYqk32ubMAu4IKsLl6YQDH0JgNuGMmQAovbHxQfYXX8VNN54Owo55lvCElD902PiMlv2sGcG7~~B6Mmg8HnA9g1ngeyYFpC53WBC3JEIVFATE9Oo6Jc8E7JtfQu-i3MnMTiabk57cnuWZg8WybFRTgsc0FTPme44FGkOYz3zwPiR7n8o1aQbv53dHXvBR-IAwBJ1NcNTASZQjK42mMRrigXGtV1iT2hTAr0VtzmabFwAA2iEijANzu0E0iFYNotGh966k5y~0-VRScRt3MERwYCl76uzojZLOOLkbWHLssbcQI8rI2iAn-du0plOylw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)