Key Points

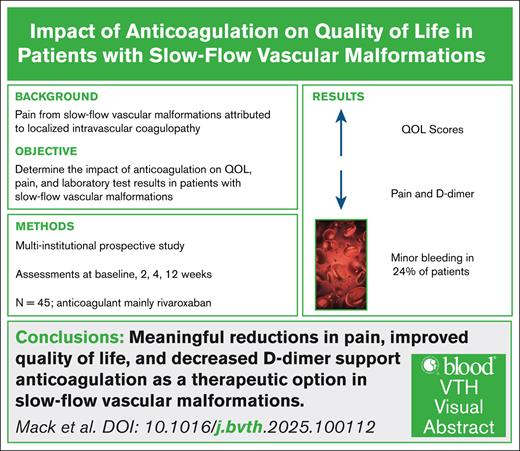

Anticoagulation improved QOL, pain, and D-dimer levels in patients with slow-flow vascular malformations.

Minor bleeding events, particularly heavy menstrual bleeding, occurred in 24% of patients, highlighting the importance of monitoring.

Visual Abstract

Pain from slow-flow vascular malformations is common, attributed to localized intravascular coagulopathy (LIC), and has a negative impact on quality of life (QOL). The use of anticoagulation has been anecdotal. The objective of this study was to determine the impact of anticoagulation in slow-flow vascular malformations on QOL, pain, and/or laboratory markers of LIC. A multi-institutional, prospective, nonrandomized institutional review board–approved observational study enrolled patients with slow-flow vascular malformation–related pain for whom anticoagulation was prescribed. Patient assessments (history, Pediatric Quality of Life survey, laboratory data) occurred at study entry, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks (optional) after starting anticoagulation. A total of 45 patients were enrolled, with a median age of 18 years (range, 5-59). The cohort consisted of 14 males (31.1%) and 31 females (68.9%). All patients were naive to anticoagulation, prescribed low-molecular-weight heparin (n = 2), rivaroxaban (n = 40), or apixaban (n = 3). Six patients (13%) were on sirolimus and 2 on daily aspirin before starting anticoagulation. Eleven patients (24%) experienced minor bleeding events, including 6 with heavy menstrual bleeding. Two patients experienced clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding leading to cessation of anticoagulation. D-dimer and pain scores decreased, and QOL survey scores increased, with all changes being statistically significant from baseline to 2 and 4 weeks. Patients with slow-flow vascular malformations had less pain and improved QOL scores and coagulation parameters when treated with anticoagulation. Nonmajor bleeding occurred, especially menorrhagia, in ∼24% of patients, demonstrating the need to monitor and balance risks against benefits.

Introduction

Vascular malformations are developmental abnormalities of the vasculature and can be defined by their endothelial cellular origins, that is, arteries, capillaries, veins, and lymphatic vessels, which can be supported histologically and radiographically. Malformations can be further classified by the velocity of blood flow through the malformation, referred to as fast/high or slow/low. Slow-flow vascular malformations are abnormal vessels with lower-than-normal blood flow velocity, resulting from the congenital inborn errors in the development of the vascular network.1 Although most slow-flow vascular malformations derive from venous vasculature, both capillary and lymphatic malformations are also considered to exhibit slow flow. Slow-flow vascular malformations may also be complex and include any combination of these 3 vessel types.2

Pain is a common manifestation of slow-flow vascular malformations with more than one-half of patients reporting pain.3 Pain in patients with slow-flow vascular malformations is highly heterogeneous and often multifactorial, making treatment challenging with a need to ascertain a deep understanding of each patient's specific pain profile. The factors that contribute to the heterogeneity of pain in slow-flow vascular malformations include the following: (1) vascular ectasia, (2) localized intravascular coagulopathy, (3) inflammation, (4) thrombosis, and (5) neuropathy. Progressive vascular ectasia likely results in pain, typically described as dull and aching in this group of patients.4 This is illustrated in patients describing aching legs every day, in the evenings, or inability to walk or stand for significant periods of time. Episodes of increased pain, described as acute and likely sharp or severe, may be triggered by infections or pubertal hormonal changes. Such pain frequently is correlated with the development of phleboliths, some of which can be superficial and recognized by the patients. This is supported by worsening of coagulation laboratory parameters (ie, elevated D-dimer and/or decreased fibrinogen), known as localized intravascular coagulopathy.3,5 Inflammation is another potential contributing factor and may be induced by infections, especially cellulitis, arthritis, and coagulopathy. Neuropathic pain is another possible contributing factor,6 happening when the malformation impinges on a nerve, or more frequently, when nerve damage follows a procedural intervention.

Management of pain due to slow-flow vascular malformations has included narcotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anxiolytics. In many patients, these medical treatments may not be effective and do not address the underlying source of pain. In slow-flow vascular malformations, abnormal blood flow and velocity interacting with dysfunctional endothelium contribute to pain through several mechanisms.7 Reducing blood flow into the malformation via external compression with adjustable garments can be an initial intervention. This mechanical approach reduces ectasia, improves flow velocity, and helps mitigate coagulopathy and phlebolith formation. When the malformation is located in an extremity, elevation of the affected limb also decreases blood flow. Procedures such as sclerotherapy and embolization are often used to further limit flow to reduce pain. Sclerotherapy also helps prevent infection, minimizes cosmetic deformity, and manages fluid accumulation. Systemic treatment of pain targets mechanisms of pain related to localized intravascular coagulopathy. Aspirin, an antiplatelet agent, was historically used with some limited benefits in patients with venous malformations but no specific guidelines exist.8 With more aggressive or aspirin-refractory pain, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) has been prescribed. In recent years, several direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have become available, initially only for adults followed by approval for use in children prompting switching from LMWH due to ease of administration.

In this study, it is hypothesized that anticoagulation (LMWH or DOAC) in patients with slow-flow vascular malformations improves quality of life (QOL) through decreases in localized intravascular coagulopathy and inflammation. The primary objective was to determine if and/or how QOL assessments change after initiation or switching (LMWH to DOAC) of anticoagulation through the use of Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL). The secondary objective was to monitor the effect of LMWH or DOAC on pain and change in coagulation and inflammatory biomarkers.

Methods

This prospective, nonrandomized, single-arm, open-label cohort multi-institutional clinical trial was conducted by the Consortium of Investigators of Vascular Anomalies and included 7 of its participating members. The trial was approved by each investigator’s affiliated institutional review board. Inclusion criteria included ages between 2 and 99 years, 1 or more slow-flow vascular malformations, planned initiation or switching (LMWH to DOAC) anticoagulation by the treating team with the primary goal of improving QOL. Anticoagulant dosing was left to the treating physician in accordance with standard clinical care but with suggested dosing as discussed subsequently. Patients on sirolimus were included if on a stable dose or goal trough level for >3 months. Based on pharmacokinetics of sirolimus and monitoring, steady state is usually achieved within 2 months of starting and changes in D-dimer and/or fibrinogen appear to be achieved within 1 to 3 months.9,10 Patients were excluded if providers planned to initiate anticoagulation only for periprocedural purposes, if they had been on sirolimus for <3 months, or they planned to initiate sirolimus or another biological inhibitor in the next 3 months. Interventional procedures and supportive care were allowed during the study.

After the enrollment, the participants underwent serial assessments at baseline, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and, if still on anticoagulation, an optional 12-week follow-up. Assessments included laboratory evaluations (list), pain score (Wong-Baker pain score), and QOL measures. Data on demographic variables, medical procedures, concurrent medications, and side effects were documented throughout the study period.

QOL measures used PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales based on patient age. Scoring for all surveys was based on a scale from 0 to 100, composed of 23 items and 4 dimensions, physical, emotional, social, and school functioning. The following 3 scores were reported: psychosocial health summary score (sum of the items divided by the number of items answered in the emotional, social, and school functioning), physical health summary score (physical functioning), and total score (sum of all the items divided by the number of items answered on all the scales). Higher scores translate into better health-related QOL.

Participants were enrolled in group 1, consisting of anticoagulation-naive patients who started LMWH or DOAC, or group 2, participants on LMWH switching to a DOAC. Although dosing was left up to the provider, recommendations for dosing of LMWH were the following: LMWH 1 mg/kg per day (divided in 2 doses) and increase by 1 mg/kg per day at 2 weeks if no or minimal benefit. If a DOAC was started, rivaroxaban was recommended at 10 mg by mouth daily and increase to 15 mg at 2 weeks if no or minimal benefit for all ages. Dosage increases were recommended in a stepwise manner to allow titration based on clinical response.

Statistical analyses

Data on dependent variables at each time period (eg, baseline, 2 weeks) were assessed for normality using histograms and the Shapiro-Wilk test. To determine whether any of the dependent variables differed significantly between time periods, a repeated measures analysis of variance was computed for each outcome using a general linear model. Significance was determined using log-transformed data for D-dimer, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and ferritin; however, descriptive statistics were displayed using untransformed values for interpretability. All other variables remained untransformed for analysis.

If a significant main effect of time period was observed in the analysis of variance, post hoc pairwise contrasts were conducted between baseline and each follow-up time point (ie, baseline vs 2 weeks, baseline vs 4 weeks, baseline vs 12 weeks). P values from these multiple contrasts were adjusted using Holm’s sequential procedure. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant after adjustment. All analyses were conducted in SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 59 patients were screened. After excluding patients with incomplete data, data from 47 participants were included in the analysis. Group 2 (patients transitioning from LMWH to DOAC) was subsequently excluded from analysis to enhance uniformity of data (study enrolled only 2 patients in that category), leaving 45 patients in group 1 (naive to anticoagulation) for analysis.

Group 1 included 2 patients treated with LMWH, 40 with rivaroxaban, and 3 with apixaban. The median age of patients was 18 years (range, 5-59). The cohort consisted of 14 males (31.1%) and 31 females (68.9%). Most patients were White (71.1%) (Table 1). More than 90% of patients had a venous component (Table 1). In addition, 39 patients (>80%) had slow-flow vascular malformations involving an extremity. Among the 40 patients on rivaroxaban, most (73%) started at 10 mg once daily. All 3 patients on apixaban were prescribed 2.5 mg twice daily. Six patients (13%) were on sirolimus before starting anticoagulation. Two patients were on daily aspirin. Compression garments were worn by 44% of patients. Procedures performed during the study period included sclerotherapy (1 at 2 weeks, 2 at 12 weeks), laser treatment (1 at 2 weeks, 2 at 4 weeks), surgical resection (1 at 12 weeks), and other procedures (1 cardiac catheterization). Several PedsQL surveys were used due to range of ages (years) of participants: parent report for young children aged 5 to 7 years (N = 3), child report aged 8 to 12 years (N = 8), teen report aged 13 to 18 years (N = 9), young adult report aged 18 to 25 years (N = 13), and adult report >26 years (N = 12). Total, physical health, and psychosocial health scores increased from baseline compared with 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks (Tables 2-4). Median total health scores for pediatric (5 to ≤18 years) and adult (19 to 59 years) patients were as follows: baseline, 70.65 and 67.39; 2 weeks, 71.74 and 81.52; 4 weeks, 73.91 and 72.28; and 12 weeks, 76.63 and 73.92, respectively. Pain scores using the Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale decreased from baseline compared with 2 and 4 weeks (Tables 2 and 3).

Laboratory evaluation for inflammatory markers which included ESR and ferritin revealed no specific trends during the study time points. Coagulation parameters included platelet, D-dimer, and fibrinogen levels only revealing a statistically significant decrease in D-dimer from baseline to 2 weeks and 4 weeks (Tables 2 and 3). Only 1 patient had a fibrinogen <100 mg/dL, and all patients had a platelet count above 130 × 103/μL throughout the study.

Bleeding adverse events included 11 patients (24%) who experienced expected minor bleeding events: 6 with heavy menstrual bleeding, 4 with bruising/bleeding after trauma, and 1 with epistaxis. Two patients experienced gross hematuria and rectal bleeding categorized as clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding leading to cessation of anticoagulation.

Discussion

Localized intravascular coagulopathy is a common feature of slow-flow vascular malformations, contributing to pain, swelling, and impaired QOL. The chronic cycle of thrombosis and fibrinolysis in these lesions is reflected by elevated D-dimer levels, which serve as a biomarker of localized intravascular coagulopathy activity.11 Slow-flow vascular malformation is an illustration of Virchow’s triad, where stasis within malformed vessels, a hypercoagulable state, and abnormal endothelium all converge to drive symptoms. Although not typically life threatening, ongoing localized intravascular coagulopathy can lead to significant morbidity, including spontaneous intralesional bleeding, thrombotic events, and functional impairment.12 Anticoagulation, particularly with LMWH, has been proposed as a therapeutic strategy to reduce localized intravascular coagulopathy–associated symptoms by improving coagulation parameters and alleviating pain.5 This study demonstrates that initiation of anticoagulation in patients with slow-flow vascular malformations improved QOL and reduced pain, accompanied by a decrease in D-dimer levels. These findings suggest that short-term anticoagulation may provide clinical benefit in slow-flow vascular malformations by disrupting the pathological thrombosis-fibrinolysis cycle.

The population study was mostly female and White patients. There are no well-established racial or sex predominance in patients with slow-flow vascular malformations. This study revealing higher prevalence in female and White individuals may reflect differences in health care access, referral patterns, or reporting bias rather than true biological differences.

Previous publications demonstrated the efficacy of LMWH in improving coagulopathy in vascular malformations, particularly perioperatively, by stabilizing hematologic parameters and reducing the risk of disseminated IV coagulation.13,14 DOACs continue to be used more in patients with slow-flow vascular malformations, especially due to the convenience of oral administration.15 This study extends these findings to DOACs, primarily rivaroxaban, revealing significant reductions in D-dimer and pain within 2 weeks of initiation. These improvements persisted at 4 and 12 weeks, supporting the hypothesis that anticoagulation mitigates the prothrombotic environment in slow-flow vascular malformations. Although the observed decrease in D-dimer levels was modest, it may still reflect a clinically meaningful reduction in localized intravascular coagulopathy; however, the magnitude of change should be interpreted cautiously given the variability in baseline levels and the absence of a control group. However, although most patients tolerated anticoagulation, nearly one-fourth experienced minor bleeding events and 2 patients developed clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding requiring treatment cessation. These findings highlight the potential risks associated with anticoagulation in this population, necessitating individualized risk assessment and close monitoring.

This study has several limitations. The nonrandomized observational design introduces selection bias, as the decision to initiate anticoagulation was left to the discretion of the treating physician. In addition, the absence of a control group precludes definitive conclusions regarding causality, as improvements in pain and QOL may have been influenced by other concurrent therapies such as compression garments or procedural interventions. Although 44% of patients reported wearing compression garments, adherence to their use was not objectively measured and may have influenced reported pain scores; similarly, interventional procedures performed during the study period, such as sclerotherapy or embolization, may have affected pain outcomes, and these variables were not uniformly controlled or accounted for in the analysis. Furthermore, the wide age range of participants (5-59 years) likely introduced significant variability in how pain and QOL were experienced and reported, particularly given the reliance on self-reported measures. Although responses were collected longitudinally, the data were analyzed at the group level rather than as within-subject changes, which may limit the ability to detect individual-level improvements or declines over time. The study was not powered to perform age-stratified analyses; however, this study observed trends between pediatric and adult patients. In pediatric patients (aged 5-18), there appeared to be a smaller improvement in QOL, with total PedsQL scores increasing from a baseline of 70.65 to 71.74 at 2 weeks. In comparison, adult patients (aged 19-59) had a more pronounced improvement at the 2-week mark, with scores increasing from 67.39 at baseline to 81.52 at 2 weeks.

The relatively small sample size further limits generalizability, particularly regarding patients treated with LMWH or apixaban. Self-reported QOL and pain scores, although valuable, introduce subjectivity and potential response bias. The number of samples for each data point (Tables 2-4) differs across tests due to challenges such as missed collections, insufficient specimen volume, or lack of reporting. Several participating institutions serve large geographic regions, including out-of-state patients, which may have further complicated data retrieval from external facilities or smaller laboratories. These factors contributed to variability in data completeness across the study. Furthermore, although D-dimer significantly decreased, other coagulation and inflammatory markers, such as fibrinogen, ESR, and ferritin, did not reveal consistent trends, warranting further investigation into their relevance in the pathophysiology of slow-flow vascular malformations.

Future studies should include randomized controlled trials to confirm the efficacy and safety of anticoagulation in patients with slow-flow vascular malformations. Stratification by underlying genetic mutations, such as TEK/TIE2 and PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum, may provide further insight into differential treatment responses. Furthermore, the optimal duration and dosing of anticoagulation therapy in this population remain unclear and should be explored in prospective trials. This study suggests that short-term anticoagulation in patients with slow-flow vascular malformations is associated with significant improvements in QOL and pain, along with reductions in D-dimer levels, supporting its role in mitigating localized intravascular coagulopathy. Given the observed bleeding complications, future studies should also incorporate standardized bleeding risk assessment tools to refine anticoagulation protocols and identify patient populations most likely to benefit while minimizing harm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study and C. D’ann Pierce for her diligent work as the study coordinator.

This research was supported, in part, by the Arkansas Children’s Research Institute and the Marion B. Lyon New Scientist Development Award (LYON4066).

Authorship

Contribution: J.M.M., S.E.C., and M.J. conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection instrument, collected data, drafted the initial manuscript, participated in the statistical analysis, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; J.B., A.B., M.R.-G., S.K., I.I., N.S., and D.A. participated in the design of the study, collected data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; and B.S. and A.T. carried out the statistical analysis and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.E.C. reports advisory board membership for Pfizer, Medexus, Sanofi, CSL Behring, and Novartis; and consultancy for data safety monitoring board of Novartis. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the Consortium of Investigators of Vascular Anomalies appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Joana M. Mack, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 1 Children’s Way, Slot 512-10A, Little Rock, AR 72202; email: jmmack@uams.edu.

Appendix

The members of the Consortium of Investigators of Vascular Anomalies are Michael Briones, Taizo Nakano, Diane Nugent, Nathan Schloemer, Adrienne Hammill, Sarah Ferri, Margaret Lee, Ginna Priola, Kristy Pilbeam, Bhuvana Setty, Anderson Collier, Francine Blei, Melinda Wu, Rachael Schulte, Whitney Eng, Beth Winger, and Juila Segal.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Joana M. Mack (jmmack@uams.edu).