Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) has transformed the treatment paradigm of relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies. Yet, this therapy is not without toxicities. While the early inflammation-mediated toxicities are now better understood, delayed hematopoietic recovery and infections result in morbidity and mortality risks that persist for months following CAR-T. The predisposition to infections is a consequence of immunosuppression from the underlying disease, prior therapies, lymphodepletion chemotherapy, delayed hematopoietic recovery, B-cell aplasia, and delayed T-cell immune reconstitution. These risks and epidemiology can vary over a post-CAR-T timeline of early (<30 days), prolonged (30-90 days), or late (>90 days) follow-up. Antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal prophylaxis; growth factors and stem cell boost to expedite count recovery; immunoglobulin replacement therapy; and possibly revaccination programs are important prevention strategies to consider for infection mitigation. Assessment of risk factors, evaluation, and treatment for pathogen(s) prevalent in a particular time frame post-CAR-T are important clinical considerations in patients presenting with clinical features suggestive of infectious pathology. As more data emerge on the topic, personalized risk assessments to inform the type and duration of prophylaxis use and planning interventions will continue to emerge. Herein, we review our current approach toward infection mitigation while recognizing that this continues to evolve and that there are differences among practices stemming from data availability limitations.

Learning Objectives

Review the risks and epidemiology of infections over post-CAR-T timeline of early, prolonged, and late follow-up

Describe infection prophylaxis and management strategies following CAR-T periods of immunosuppression

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) has offered a promising breakthrough in the therapeutic paradigm of relapsed and refractory B-cell malignancies.1 The role is now evolving beyond hematological malignancies. CAR constructs vary in design and targets, but several common attributes and toxicities post-CAR-T are a treatment class effect. These include cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), immune effector cell–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like syndrome (IEC-HS), delayed hematopoietic recovery (also referred to as immune effector cell–associated hematotoxicity), and infections.2-8 While CRS, ICANS, and IEC-HS, mediated by cytokines resulting from CAR T-cell expansion, occur in the early post-CAR-T period, cytopenias and infections can persist or appear for several months, necessitating extended post-CAR-T monitoring for select patients. Practices for infection surveillance and prophylaxis across clinical trials vary, and retrospective data are often limited by sample size. We share our approach to mitigating and managing infections in CAR-T patients, delineating our rationale and highlighting variations across practices.

We approach the post-CAR-T timeline of immunosuppression as that of post-CAR-T cytopenias and divide as (1) early, ie, within 30 days, when immunosuppression is most pronounced amid cell count nadirs; (2) prolonged (days 30-90), ie, after expected early neutrophil recovery but with absent B-cell or T-cell recovery; or (3) late, ie, beyond day 90 driven by delayed host T-cell recovery.9 Herein, we review infection mitigation strategies pre- and post-CAR-T over this timeline.

Pre-CAR-T infection mitigation

Preexisting risk factors

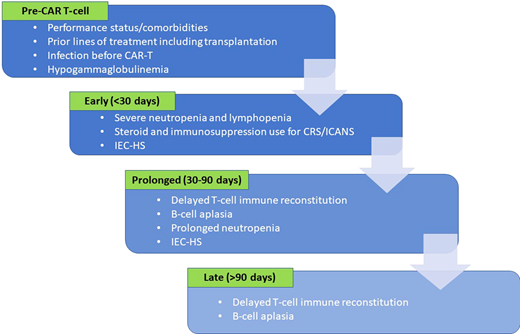

The majority of patients are immunosuppressed before CAR-T, which predisposes them to infections after infusion. Specific risk factors (Figure 1) are related to disease- or treatment-related immunosuppression and to patient frailty related to performance status or comorbidities.10-14 While the use of CAR-T in patients who have undergone a prior blood or marrow transplantation (BMT) is feasible,15 prior BMT and higher number of prior therapies are linked to increased risk of infections.10,11,14 Infections in the 3 months preceding CAR-T, suggesting preexisting immunosuppression, indicate higher risk of post-CAR-T infections.11-13 In multiple myeloma patients, CD38-targeted therapy, often used before CAR-T, can result in hypogammaglobulinemia and blunted humoral immune response.16 Taken together, these risk factors can inform planning for infection prophylaxis and monitoring following CAR-T.

Risk factors for infections in the various time frames following CAR T-cell infusion.

Risk factors for infections in the various time frames following CAR T-cell infusion.

CLINICAL CASE

A 67-year-old man with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) presents to clinic to discuss CAR-T. Prior treatments include rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (RCHOP), to which the lymphoma was refractory, and CD19-CAR-T is now considered. His most recent evaluation prior to starting RCHOP was negative for hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen but positive for HBV core and surface antibody, for which he is on entecavir prophylaxis. CT scan showed multistation lymphadenopathy, consistent with lymphoma. What additional testing needs to be done before CAR-T?

Pre-CAR-T screening

Before embarking on the CAR-T schema of lymphodepletion chemotherapy (LD) and CAR T-cell infusion followed by a variable although extended period of immunosuppression, we evaluate patients for existing infections that may reactivate after CAR-T. Screening evaluations, summarized in Table 1, are usually performed within 30 days before LD although some of this testing may occur before leukapheresis and doesn't require repeat testing.

For an individual patient, assessment for specific or localizing symptoms, physical exam, geographical location, or prior imaging that suggests an existing infection can guide further screening. We test all patients for HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). While deemed safe to pursue CAR-T in a setting of concomitant or prior exposure to HBV or HCV, HBV reactivations post-CAR-T have been reported.17-19 Patients with a positive HBV core antibody receive antiviral prophylaxis with entecavir or tenofovir for at least 12 months after CAR-T. Patients with active or chronic HBV or HCV or HIV are managed in close consultation with hepatology and/or infectious disease experts for treatment and monitoring.

Since the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and during flu season, we screen all patients for respiratory viruses via nucleic acid test. This practice has varied across centers. Nevertheless, symptoms or known exposure warrants testing for respiratory viruses, often followed by lung imaging in patients who test positive or report symptoms to suggest a lower respiratory infection. Various studies had suggested a variable incidence of severe COVID-19 in CAR-T recipients and high risk of mortality.20,21 Our practice is to delay CAR-T by at least a week (ideally 14 days) for patients with a new positive COVID-19 test, regardless of symptoms. We do not usually repeat testing after symptoms resolve. A recent retrospective study identified 11 patients with COVID-19 within 90 days of CAR-T, 10 of whom had asymptomatic or mild infections.22 No recrudescence of COVID was noted after CAR-T, although delays were common. Further studies accounting for the presence and severity of symptoms, lower respiratory lung involvement, pretreatment levels of inflammatory markers, recent upper or lower respiratory infections, and urgency posed by disease status are needed to evaluate a case-based approach in order to determine optimal timing of CAR-T for patients who are COVID-19 positive.

Additional testing for specific viruses, parasites, and fungi as delineated in Table 1 is warranted for patients with epidemiologic risk or prior history of infections. Serologies for herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, and/or varicella zoster virus (VZV) are tested if patients are not on antiviral prophylaxis. We do not routinely screen for or monitor serum or plasma nucleic acid test for other herpesviruses (cytomegalovirus [CMV] or Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]) unless the patient underwent a BMT within 6 to 12 months.

Early post-CAR-T (<30 days) infection mitigation

Risks and epidemiology

LD prior to CAR-T improves CAR T-cell expansion and persistence by eliminating endogenous lymphocytes, reducing immunosuppressive regulatory T-cells, and removing immunostimulatory cytokine sinks.23,24 Lymphodepletion, as the term suggests, causes cytopenias, usually severe lymphopenia, and neutropenia (<500 cells/mm3) early post-CAR-T, which increases the risk of infections.4 Other frequent events here include inflammatory toxicities like CRS or ICANS, which require immunosuppressive treatment, often corticosteroids.3,25 Consequently, infections are at the forefront of possible complications early post-CAR-T, and preventive strategies are crucial to contain this incidence.

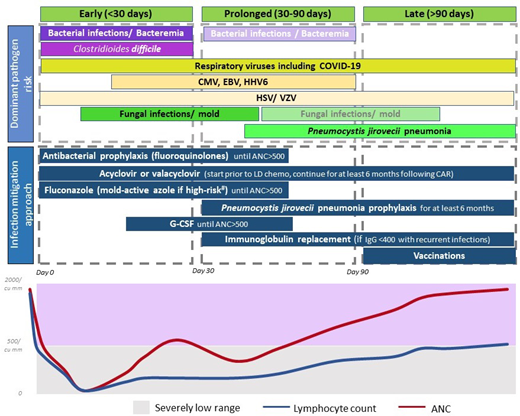

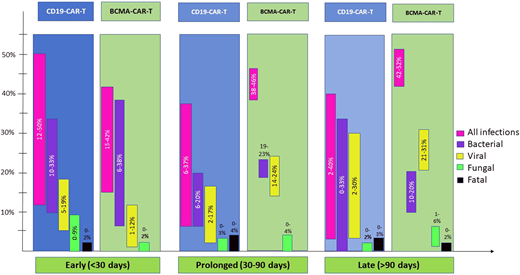

Risks and patterns of infections with CD19- vs B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-directed CAR-T can vary as depicted in Figure 2. Additional details of all infections and pathogens by CAR-T target are tabulated in Table 2, and bacterial infections in the early post-CAR-T period are in Table 3.

CD19-directed CAR T-cells

The density of infections is highest in the first month, dominated by bacterial and viral pathogens.11,12,14,26 Both bacterial bloodstream and site infections (with organ involvement like pneumonia, colitis, or urinary tract infection) are common and reported in approximately one-third of patients (Figure 2). Clostridioides difficile was the most commonly identified organism, accounting for as high as one-third of bacterial infections in the first 30 days.7,11,12 Since Clostridioides difficile colonization is prevalent in patients undergoing chemotherapy and transplantation, this is not surprising but draws attention to testing methodology in patients with known colonization.27,28 Viral infections early post-CAR-T are mostly respiratory. Infrequently human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6, ~6%) and CMV (~20%) reactivations, mostly without end-organ involvement, are seen.29-31 Fungal infections are rare (<5% in most series7,10,11,14,32) but can be life-threatening or fatal.7

BCMA-directed CAR T-cells

Limited data are available on infections due to a more recent commercial use but suggest that approximately 40% of patients develop infections early post-BCMA-CAR-T, although 1 report from Kambhampati et al reports a lower incidence at 15%.6,11,13,33 In a combined report of CD19- and BCMA-directed CAR-T (among other targets) by Mikkilineni et al, myeloma patients had the highest proportion of infections early post-CAR-T.11 Frequency of bacterial and viral infections early post-BCMA-CAR-T is similar.6,33 Viral infections remain predominantly respiratory, but CMV viremia is also commonly seen with BCMA-CAR-T (46%).13,29 Fungal infections are infrequent although early mortality from disseminated fungal infection has been reported; so caution similar to CD19-CAR-T is warranted.33

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient was tested for HBV surface antigen in addition to the testing in Table 1. HBV surface antigen remained negative. At the time of CAR-T, he remained on entecavir and valacyclovir prophylaxis. He started fludarabine and cyclophosphamide LD and received axicabtagene ciloleucel on day 0. Blood counts on day 0 were absolute neutrophil count (ANC) 300/µL, hemoglobin 9.5 g/dL, and platelets 90 × 103/µL. What additional infection prophylaxis could be considered at this time?

Infection mitigation and management

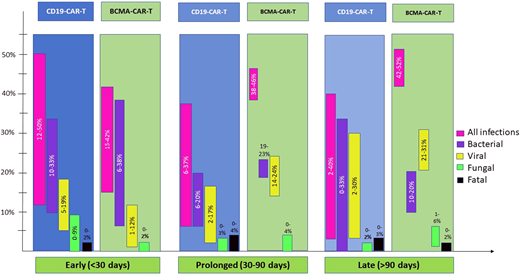

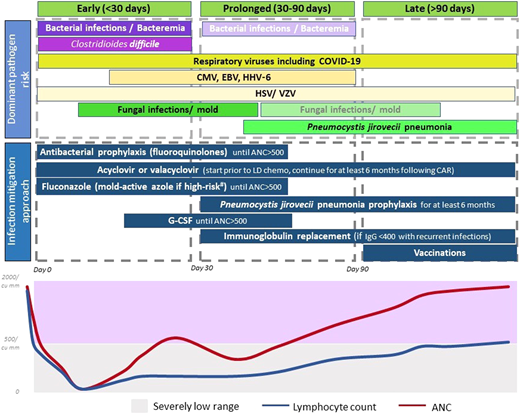

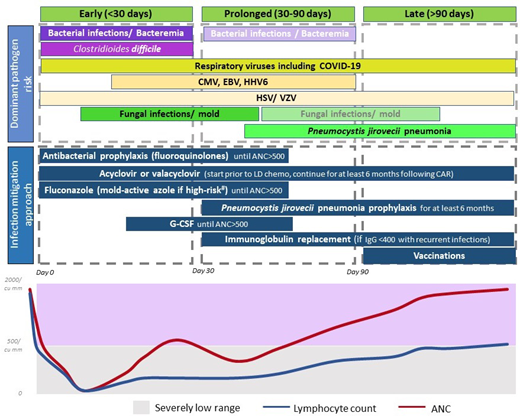

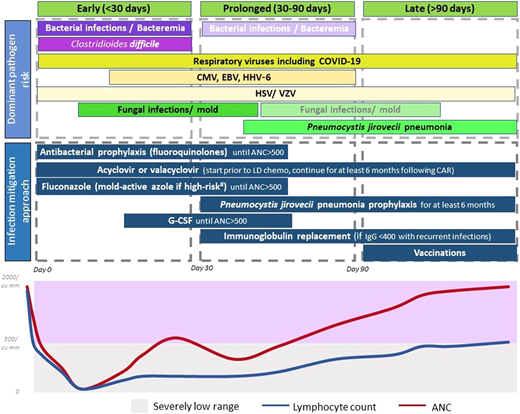

The currently adopted approach for infection mitigation at our center is depicted in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 4. We recognize the lack of prospective or comparative data, variations across studies and institutions, and ever-emerging practices in light of evolving data. We start antibacterial (fluoroquinolones preferred), and antifungal prophylaxis (usually fluconazole), during severe neutropenia. In patients at a higher risk of mold infections—ie, those who receive steroids for >3 days post-CAR-T, have prolonged severe neutropenia beyond 4 weeks, underwent a BMT in the preceding 12 months, or have peri-CAR-T exposure to Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors—we use a mold-active azole for prophylaxis.34 Most patients are already on acyclovir or valacyclovir for HSV and VZV prophylaxis, and that is continued for at least 6 months post-CAR-T. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP) prophylaxis with sulfamethoxazole- trimethoprim or atovaquone starts around day 28 and continues for at least 6 months, often up to 12 months. When possible, we prefer to use CD4+ T-cell recovery (>200/mm3) to guide duration of PJP prophylaxis.

Dominant pathogen risk over the post-CAR-T timeline. *Fading boxes for the same pathogen over time suggest a lower risk of the pathogen in that time frame. **If a pathogen is not included in a time frame, it suggests that the risk is lower (not absent). Clinical consideration should be made as appropriate. #High-risk factors considered for invasive mold infection include prolonged severe neutropenia, recent BMT, prolonged use of steroids, and use of BTK inhibitors.

Dominant pathogen risk over the post-CAR-T timeline. *Fading boxes for the same pathogen over time suggest a lower risk of the pathogen in that time frame. **If a pathogen is not included in a time frame, it suggests that the risk is lower (not absent). Clinical consideration should be made as appropriate. #High-risk factors considered for invasive mold infection include prolonged severe neutropenia, recent BMT, prolonged use of steroids, and use of BTK inhibitors.

Other infection mitigation strategies include administration of growth factors if ANC remains below 500/µL beyond day 14, and we have not observed excess CRS or ICANS with this approach. Some centers now start growth factors within a week following CAR-T, and this has not demonstrated a difference in toxicity or efficacy.35 Viral monitoring for CMV or HHV-6, commonly done after BMT, has varied across centers after CAR-T. Until recently, we did not routinely monitor for viral reactivations except in patients with recent BMT (within 6-12 months). A recent report showed CMV reactivation in as high as 25% of patients, and reactivation was prominent in patients who received BCMA-CAR-T, or >3 days of corticosteroids.29 Anecdotally, we detected CMV viremia in a patient with abdominal symptoms (no biopsy), which improved with CMV treatment. Now, we monitor CMV weekly in BCMA-CAR-T patients or those who receive steroids for >3 days for 1 month and test for CMV in patients with fever or other clinical features suggestive of infections, without another identifiable etiology.

For early post-CAR-T fever, CRS is the most common etiology in the first 2 weeks. If ANC <500/µL, infection workup is commonly pursued, including blood cultures and source localization. Imaging with CT scans is pursued only in patients with localizing symptoms or persistent fevers despite CRS treatment. We start empiric antibiotic coverage with intravenous antipseudomonal beta-lactams, and cefepime is preferred over piperacillin-tazobactam.36 Central line is evaluated and intravenous vancomycin is initiated for concerns of line infection. For patients with persistent fevers or imaging findings concerning for fungal infection, noninvasive fungal markers are tested, and bronchoscopy is considered.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient developed grade 3 CRS on day 6 and grade 2 ICANS on day 11, which resolved with the use of tocilizumab (CRS) and steroids (ICANS) by day 15. Severe neutropenia persisted for 46 days post-CAR-T; and moxifloxacin and growth factors were continued until then. Fluconazole was changed to posaconazole around day 15. Atovaquone was started on day 28. He is now day 52 from CAR-T infusion. What additional interventions could be considered at this time?

Prolonged post-CAR-T (30-90 days) infection mitigation

Risks and epidemiology

Between days 30 and 90, severe neutropenia can persist in 10% to 20% patients.4,31 CRS and ICANS are unlikely beyond day 14, but immunosuppression for IEC-HS can continue beyond day 30.37,38 T-cell recovery is unlikely during this period after LD.7 Profound and prolonged B-cell aplasia, which is a well- recognized on-target, off-tumor effect of CAR-T, is common both with CD19- and BCMA-CAR-T and results in impaired humoral immune responses.14,31,39 Together, these factors result in continued, albeit lower, risk of infections.

CD19-directed CAR T-cells

BCMA-directed CAR T-cells

Unlike CD19-CAR-T, infection risk remained 38% and 46% in the prolonged post-BCMA-CAR-T follow-up in two studies with detailed data.6,13 In fact, median time to first infection post-BCMA-CAR-T was 46 days.33 Respiratory viruses, including COVID-19, were mostly implicated.6 CMV reactivation is more frequent in BCMA-CAR-T than CD19-CAR-T patients.29

Infection mitigation and management

As shown in Figure 3 and Table 4, antibacterial and antifungal prophylaxis and growth factors are continued in patients with prolonged severe neutropenia. Immunoglobulin replacement every 3 to 4 weeks is recommended for patients with IgG levels <400 mg/dL complicated by recurrent infections especially sinopulmonary bacterial infections.41 Given the higher risk of infections and lower pathogen-specific immunoglobulins noted after BCMA-CAR-T, some practices also favor immunoglobulin replacement in all recipients of BCMA-CAR-T regardless of infections. In the young adult population, immunoglobulin replacement is often recommended with low IgG levels regardless of recurrent infections.10,26 Patients with severely low levels of IgG (<200 mg/dL) or extremely low IgA levels are also considered for immunoglobulin replacement.2

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Immunoglobulin levels remained around 300 mg/dL for our patient without excess infections. At day 96, he is in complete remission with improved counts (ANC 1200/µL) and wishes to transition care back to his local oncologist. What recommendations should be conveyed at this transition of care?

Late post-CAR-T (>90 days) infection mitigation

Risks and epidemiology

Beyond day 90, the infection risk is lower but continues to loom from hypogammaglobulinemia, B-cell aplasia, and impaired T-cell reconstitution. After CD19-CAR-T-cell therapy, CD4+ T cells can remain <200/µL up to 12 months post-CAR-T.7,31 B-cell aplasia persists in >40% of patients beyond 6 months both with CD19- and BCMA-CAR-T.13,31,41 Hence, detailing infection prevention and management is critical when transitioning care locally, which often happens at this time.

CD19-directed CAR T-cells

Data become scant for late follow-up, but reported rates are low (2%-5%),40,42 except 1 study with infection events of approximately 40% with axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel.12 PJP occurs late post-CAR-T, usually after discontinuation of prophylaxis.12,31,32 Influenza- and PJP-related deaths have been reported in 1 patient each beyond 90 days.12,31

BCMA-directed CAR T-cells

One study is available for late post-BCMA-CAR-T follow-up and reports infections in over 40% of patients.13 One fatality was reported from Aspergillus following influenza after 90 days post-CAR-T. Of note, no confirmed PJP has been reported with BCMA.

Infection mitigation and management

As discussed, we continue PJP prophylaxis for 6 to 12 months post-CAR-T. Since rare cases of PJP have been reported after cessation of prophylaxis, when possible, we prefer to use CD4+ T-cell recovery >200/µL to guide prophylaxis cessation. Acyclovir/valacyclovir prophylaxis also continues for at least 6 months. Prompt evaluation and management for respiratory viruses with known exposure or respiratory symptoms are also warranted.

Vaccinations

Post-CAR-T vaccination is one of the most heterogeneous areas of practice within CAR-T, and often derived from BMT. Patients with lymphoma and multiple myeloma, where CAR-T is most commonly used, have impaired humoral and cellular immunity. One prospective cross-sectional study in CAR-T patients showed that less than half the patients had seroprotection for mumps, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type b, Streptococcus pneumoniae, or Bordetella pertussis.43 Fewer BCMA-CAR-T recipients had pathogen-specific immunoglobulins and seropositive titers, attributed to the depletion of plasma cells that generate immunoglobulins specific to previously exposed pathogens.43 Hence, immunoglobulin replacement and vaccinations are particularly valuable after BCMA-CAR-T. In light of these findings, we usually start vaccinations (for Streptococcus pneumoniae, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) at 6 months post-CAR-T unless there are concerns for immunosuppression or the patient is undergoing BMT. We delay live vaccinations to at least 1 year given the pattern of immune reconstitution.

For severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), outcomes following CAR-T have been poor, with mortality rates of approximately 30%.44,45 Furthermore, rates of seroconversion postvaccination are low in CAR-T recipients, ranging from 11% to 29% in different studies.45,46 A multicenter prospective cohort of 65 CAR-T recipients suggests that patients who receive SARS-CoV-2 vaccination within 4 months of CAR-T have a higher likelihood of antibody responses than those who received vaccination 4 to 12 months from infusion, while T-cell responses were similar.47 Lastly, humoral immunity from pre-CAR-T SARS-CoV-2 vaccination appears to persist post-CAR-T, and previously vaccinated patients have higher immunoglobulin and T-cell responses post-CAR-T vaccination. This has informed the practice to vaccinate for SARS-CoV-2 before CAR-T and then revaccinate (3 doses every 2 months) starting at 3 to 4 months. Similar data exist supporting vaccination for seasonal influenza before CAR-T in addition to post-CAR-T.48

Future directions: toward personalized care

Elucidation of the efficacy of commonly practiced interventions and exploration of personalized strategies are needed. A better understanding of risk factors and stratification thereof can inform a more tailored approach and minimize emergence of resistant organisms. Rejeski et al have recently described the CAR-HEMATOTOX model to predict post-CAR-T-cell risk of severe infections.49,50 Patients with high risk by the CAR- HEMATOTOX tool were more likely to develop severe infection during early and prolonged post-CAR-T and benefited from antibacterial prophylaxis, which reduced bacterial infections. Additional risk factors that are relevant in developing such a risk stratification include prior BMT, type of CAR construct, immunosuppression for CAR-T toxicities, and history of infections, among other factors. Future studies are needed to further optimize risk assessment to broaden the scope of their use in mitigating infectious risks.

Summary

Risk of infections following CAR-T is real. Many are avoidable with prevention strategies, and early intervention is critical. Risk of infection appears higher with BCMA-CAR-T and remains even in the late follow-up. An explicit transition of care to referring teams is valuable as much of the late follow-up may occur away from tertiary centers. Prospective research toward standardized and personalized approaches is needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of nurse practitioner Julie Baker, Dr. S. Abbas Ali, and Dr. John Baddley for their thoughtful insight and review of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was used for the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Nadeem Tabbara has no competing financial interests to declare.

M. Veronica Dioverti-Prono reports consultancy fees for Regeneron and research funding from AlloVir and Regeneron.

Tania Jain reports institutional research funding from CTI BioPharma, Kartos Therapeutics, Incyte, and Bristol Myers Squibb and advisory board participation with Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte, AbbVie, CTI, Kite, Cogent Biosciences, Blueprint Medicines, Telios Pharma, Protagonist Therapeutics, Galapagos, TScan Therapeutics, Karyopharm, and MorphoSys.

Off-label drug use

Nadeem Tabbara: nothing to disclose.

M. Veronica Dioverti-Prono: nothing to disclose.

Tania Jain: nothing to disclose.