Abstract

The ongoing development of molecularly targeted therapies in addition to the new standard of care combination of azacitidine and venetoclax (AZA-VEN) has transformed the prognostic outlook for older, transplant-ineligible patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). While conventional treatments, such as standard anthracycline and cytarabine- based chemotherapy or hypomethylating agent (HMA) monotherapy, are associated with a generally poor prognosis in this patient population, the use of these novel regimens can result in long-lasting, durable remissions in select patient subgroups. Furthermore, the simultaneous discovery of resistance mechanisms to targeted therapies and AZA-VEN has enabled the identification of patient subgroups with inferior outcomes, leading to the development, of new risk-stratification models and clinical investigations incorporating targeted therapies using an HMA-VEN–based platform. Treatments inclusive of IDH1, IDH2, FLT3, and menin inhibitors combined with HMA-VEN have additionally demonstrated safety and high rates of efficacy in early-phase clinical trials, suggesting these regimens may further improve outcomes within select subgroups of patients with AML in the near future. Additional studies defining the prognostic role of measurable residual disease following VEN-based treatment have further advanced prognostication capabilities and increased the ability for close disease monitoring and early targeted intervention prior to morphologic relapse. This review summarizes these recent developments and their impact on the treatment and survival of transplant-ineligible patients living with AML.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the impact of baseline genomics on outcomes for patients with AML treated with lower-intensity regimens

Recognize patient subgroups that may benefit from novel treatment approaches combining targeted therapy with hypomethylating agents

CLINICAL CASE

A 73-year-old man with a history of head and neck cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and congestive heart failure presents with anemia, neutropenia, and circulating blasts. A bone marrow biopsy confirms a diagnosis of AML. Additional testing reveals a diploid karyotype and mutations in DNMT3A and IDH1. Given his comorbidities, he is not considered a candidate for induction chemotherapy.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a life-threatening hematologic malignancy primarily occurring in older adults (median age at diagnosis: 69 years).1 Historically, older patients with AML experience poor survival due to increased treatment-related mortality, adverse-risk molecular characteristics, and persistent measurable residual disease (MRD) resulting in disease relapse.2-5

Long-term survival rates of 30% to 60% are realized following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), yet only approximately 30% of patients successfully proceed with HCT in remission.6,7 Increasing age, concurrent comorbidities, and primary refractory disease limit the applicability of both intensive chemotherapy (IC) and HCT in older patients.8 In this setting, combination therapies with azacitidine plus venetoclax (AZA-VEN) and azacitidine plus ivosidenib (AZA-IVO; approved for newly diagnosed AML with a concurrent IDH1 mutation) are now standard treatments that have transformed outcomes in this difficult to treat population.9,10

Translational studies developed alongside the rapid clinical adoption of AZA-VEN characterized key resistance mechanisms and patient subgroups with differing prognoses.11-20 New treatment-specific risk models, molecular and/or flow-cytometric (MFC)–based MRD monitoring and intervention, and emerging targeted therapy combinations are enabling treatment individualization and further improving clinical outcomes.21-28

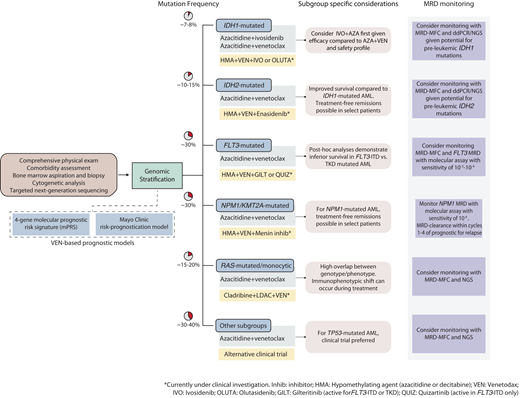

With these advancements, the treatment outlook for older, unfit patients with AML has simultaneously become more optimistic while becoming increasingly complex and individualized. This review summarizes current and emerging lower-intensity treatment perspectives for older, unfit patients with AML and provides a practical framework to guide clinical decisions across genetically defined AML subgroups (Figure 1).

Contemporary treatment approach for transplant-ineligible patients with AML. The initial evaluation should consist of a comprehensive history and physical exam to ascertain the patient's fitness and ability to undergo leukemia-directed therapy, followed by a bone marrow examination with special attention to cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities that can inform treatment selection and prognosis. Risk-stratification using either the 4-gene prognostic risk signature or Mayo Clinic risk-prognostication model (after initiation of therapy) may provide important prognostic information. For patients with IDH1-mutated AML, AZA-IVO may be preferred over HMA-VEN. For patients with TP53-mutated AML, a clinical trial option is preferred over HMA-VEN if available. Ongoing clinical trials (highlighted in yellow boxes) are actively investigating targeted therapies in combination with HMA-VEN in molecularly informed patient subgroups.

Contemporary treatment approach for transplant-ineligible patients with AML. The initial evaluation should consist of a comprehensive history and physical exam to ascertain the patient's fitness and ability to undergo leukemia-directed therapy, followed by a bone marrow examination with special attention to cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities that can inform treatment selection and prognosis. Risk-stratification using either the 4-gene prognostic risk signature or Mayo Clinic risk-prognostication model (after initiation of therapy) may provide important prognostic information. For patients with IDH1-mutated AML, AZA-IVO may be preferred over HMA-VEN. For patients with TP53-mutated AML, a clinical trial option is preferred over HMA-VEN if available. Ongoing clinical trials (highlighted in yellow boxes) are actively investigating targeted therapies in combination with HMA-VEN in molecularly informed patient subgroups.

Molecular prognostication in the setting of lower- intensity treatments for AML

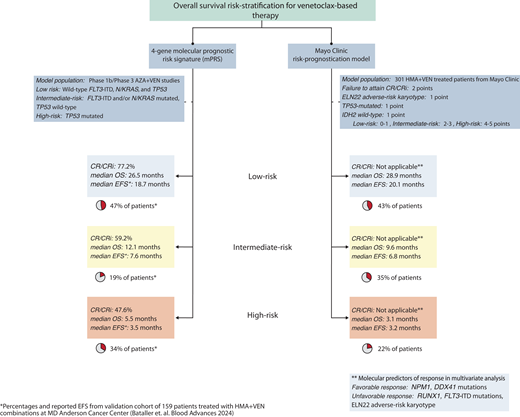

The European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022 guidelines, developed from younger patients with AML treated with standard IC, inadequately risk stratify patients receiving HMA-VEN therapy.21,29,30 Two newer treatment-specific risk-stratification models for HMA-VEN are now available (Figure 2).21,22

Risk-stratification models for patients receiving HMA-VEN therapies. Two models available for use include the molecular prognostic risk signature (mPRS) and Mayo Clinic risk-prognostication model. The mPRS utilizes 4 key genes (N/KRAS, FLT3-ITD, and TP53) to characterize patients into higher-benefit (ie, low-risk), intermediate-benefit, and lower-benefit (ie, high-risk) groups. Of note, using this 4-gene model, approximately 40% to 50% of patients will be characterized as higher benefit. The Mayo Clinic risk- prognostication model classifies patients into low, intermediate, and high-risk groups based on the incorporation of molecular and response features. Similar to the mPRS model, approximately 40% of patients are categorized as low risk.

Risk-stratification models for patients receiving HMA-VEN therapies. Two models available for use include the molecular prognostic risk signature (mPRS) and Mayo Clinic risk-prognostication model. The mPRS utilizes 4 key genes (N/KRAS, FLT3-ITD, and TP53) to characterize patients into higher-benefit (ie, low-risk), intermediate-benefit, and lower-benefit (ie, high-risk) groups. Of note, using this 4-gene model, approximately 40% to 50% of patients will be characterized as higher benefit. The Mayo Clinic risk- prognostication model classifies patients into low, intermediate, and high-risk groups based on the incorporation of molecular and response features. Similar to the mPRS model, approximately 40% of patients are categorized as low risk.

The 4-gene molecular prognostic-risk signature (mPRS) proposed by Döhner et al defines 3 groups based on the phase 3 VIALE-A treatment population: higher benefit (wild-type FLT3-ITD, N/KRAS, and TP53), intermediate (a mutation in either FLT3-ITD and/or N/KRAS and wild-type TP53), and lower benefit (presence of a TP53 mutation) corresponding to a median overall survival (OS) of 24, 12, and less than 6 months, respectively.30 The lower-benefit group was enriched for patients with complex cytogenetics (89%), which, while not predictive of VEN resistance in isolation, are frequently associated with TP53 mutations.13,31

A validation study supports the utility of the mPRS compared to ELN 2022.21 Across the higher, intermediate, and lower- benefit groups, the CR/CRi rates were 86%, 54%, and 59%, and the median OS was 30, 12, and 5 months with a 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse of 35%, 70%, and 60%, respectively. A minority (12%) of patients received HCT in remission. Thirty-five percent of patients classified as ELN adverse risk were reallocated into the mPRS higher-benefit group, likely a reflection of ascribing myelodysplasia-related mutations (ASXL1, RUNX1, SRSF2, SF3B1, U2AF1, ZRSR2, EHZ2, BCOR, STAG2) as adverse risk in ELN 2022 guidelines.32 This latter point highlights that molecular- based prognostication models are treatment-specific. Prior studies demonstrated that VEN-based therapies attenuate the inferior survival associated with myelodysplasia-related mutations in the setting of IC.33-35

The Mayo Clinic risk-prognostication model incorporates cytogenetics, mutational status, and clinical response.22 Favorable mutations predictive of an increased likelihood of CR/CRi included NPM1, IDH2, and/or DDX41, while unfavorable cytogenetics, mutated FLT3-ITD, or RUNX1 corresponded with lower CR/CRi rates with HMA-VEN regimens. Multivariate analysis identified the failure to attain CR/CRi, ELN 2022 adverse-risk cytogenetics, the presence of a TP53-mutation, and the lack of an IDH2 mutation as significant predictors of inferior survival, permitting development of a response-based prognostic score allocating patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups.22 The 3-year OS (censored for HCT) across these groups was 42%, 5%, and 0%, respectively. Like the mPRS population, only 13% of patients received HCT.

An expanded set of mutations now predict favorable responses and survival following VEN-based therapy, including mutated NPM1, IDH2, or DDX41, particularly in the absence of signaling mutations.9-14,19,20,30 The higher-benefit group from the mPRS (median OS, 30 months; 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse, 35%) and the low-risk group from the Mayo Clinic model (3-year OS, 42%) identify patients with improved long-term survival with HMA-VEN regimens. These outcomes compare favorably to reported survival in transplant-eligible patients over age 60 undergoing HCT.8,36 Some patients may additionally experience improved fitness following treatment enabling HCT candidacy, which should remain an important consideration for all patients receiving HMA-VEN therapy as this therapy is not considered curative in the majority of patients.37

The mPRS and Mayo Clinic models differ slightly in prognostication, likely related to the inclusion of CR/CRi as a variable within the Mayo Clinic model and different frequencies in prognostic gene mutations and co-occurring mutations between cohorts.

Treatment approaches for IDH1/2-mutated AML

Long-term survival data from the phase 3 VIALE-A trial identified differing outcomes between patients with IDH1 vs IDH2 mutations (median OS of 10.2 vs 27.5 months), with IDH2-mutated AML experiencing particularly favorable outcomes following HMA-VEN (Table 1).38

For IDH1-mutated AML, treatment with the IDH1 inhibitor ivosidenib in combination with azacitidine (IVO-AZA) is generally preferred based on data from the phase 3 AGILE trial, a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study evaluating IVO-AZA vs AZA-placebo (Table 2).10 IVO-AZA improved event-free survival vs AZA-placebo (hazard ratio, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.16-0.69; P = .002).10 An updated OS analysis with a median follow-up of 28.6 months continues to favor IVO-AZA vs AZA-placebo (29.3 vs 7.9 months; P < .0001).39 Compared with the more cytotoxic activity of HMA-VEN (median time to CR/CRi, 1.2 months), responses occurred more slowly with IVO-AZA (median time to CR/CRh, 4 months); however, composite CR/CRi rates (54% vs 67%) and median duration of response (not reached vs 22 months) are comparable.10,18 Rates of grade 3 or greater febrile neutropenia (28% vs 42%) and infections of any grade (28% vs 59%) appear to favor IVO-AZA vs AZA-VEN,9,10 although QTc prolongation and IDH-inhibitor related differentiation syndrome (IDH-DS) are higher with AZA-IVO (Table 3).10

Key questions remain concerning optimizing the use of these 2 effective doublets in IDH1-mutated AML and, more broadly, about sequencing, combining targeted therapies, and the role of MRD-monitoring in IDH1/2-mutated AML.

Prospective data on sequencing remain sparse. Incorporating an IDH inhibitor with an HMA-VEN backbone may improve response and survival compared to use following HMA-VEN therapy.40,41 In 1 retrospective analysis, salvage response rates using HMA-VEN after receipt of a frontline IDH inhibitor–based regimen were 88% vs 56% when using an IDH inhibitor following HMA-VEN.40 Most (60%) of these latter responses were observed when IDH inhibitors were integrated as triplet regimens with continuation of the HMA-VEN backbone. Few patients (8%) enrolled in VIALE-A with IDH1/2-mutated AML received IDH inhibitors at progression, and data on the use of HMA-VEN following IVO-AZA are not readily available.38 The I-DATA study (NCT05401097) will attempt to prospectively answer questions pertaining to the optimal sequencing of treatment in IDH1-mutated AML.

If ongoing studies confirm tolerability, “triplet” therapy combining IDH1/2 inhibitors with an HMA-VEN backbone may optimize therapy in patients with IDH1/2 mutations (Table 2).23,42 High composite CR rates were observed in patients with newly diagnosed AML treated with the triplet of IVO-VEN-AZA (93%; N = 13/14), IVO in combination with oral decitabine (ASTX-727, decitabine/cedazuridine [C-DEC]) and VEN (90%; N = 9/10), or the IDH2 inhibitor enasidenib with C-DEC–VEN (100%; N = 14/14).23,42 This latter combination appears to further increase activity in patients with IDH2-mutated AML compared to the doublet of enasidenib-AZA, which improved CR/CRi rates compared with AZA monotherapy.43

After a median follow-up of 24 months, the estimated 24-month OS of 67% in patients with newly diagnosed AML treated with IVO-VEN-AZA compares favorably to reported outcomes with AZA-VEN or IVO-AZA, respectively.23

Additionally, triplet therapy incorporating IVO or ENA resulted in MRD-negative (measured using MFC) remissions in 80% to 83% and 93% of patients with newly diagnosed IDH1- or IDH2-mutated AML, which compares favorably to MRD-MFC negative rates observed with AZA-VEN (42% and 50%, respectively).23,42IDH1 mutation clearance by droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR) occurred in 64% of patients receiving 5 or more cycles of IVO-VEN-AZA.23 While MFC was prognostic, molecular clearance did not correspond with survival, similar to recent reports that IDH1/2 mutations in remission following IC do not influence disease relapse post HCT.23,44

Two planned studies inclusive of larger patient cohorts in the NCI MyeloMatch initiative will provide additional insight into the benefit of frontline triplet therapy in IDH1/2-mutated AML, prospectively randomizing patients to an all-oral combination of C-DEC-VEN and an IDH1 or IDH2 inhibitor vs C-DEC-VEN.

Treatment for FLT3-mutated AML

Responses in patients with FLT3-ITD–mutated AML are improved with AZA-VEN vs AZA monotherapy (CR/CRi, 63% vs 46%)12; however, survival remains suboptimal and is similar between AZA-VEN vs AZA (median OS, 9.9 vs 8.5 months) (Table 1).12 Fortunately, trials incorporating targeted therapy appear to improve response rates and survival in this higher-risk molecular subgroup; once combination dosing and schedules are established, these may soon represent a new standard of care.

More specifically, marked activity is observed when incorporating the type 2 FLT3 inhibitor gilteritinib with VEN as a doublet, or AZA-VEN-GILT as a triplet (Table 2).24,45 The frontline use of AZA-VEN-GILT resulted in a CR/CRi rate of 96% (N = 29/30), including 93% of patients attaining MRD-MFC negative remissions and 65% attaining FLT3-ITD levels of less than 5 × 10−5 following 4 cycles of therapy.24 After a median follow-up of 19.3 months, the estimated 18-month relapse-free survival and OS were 71% and 72%, respectively. Frontline use of the type 1 FLT3 inhibitor quizartinib with decitabine-VEN (DAC-VEN-QUIZ) demonstrated similarly impressive response rates.46 DAC-VEN-QUIZ resulted in a CR/CRi in 100% (N = 10/10) of patients, including 75% with undetectable FLT3-ITD PCR.46 After a median follow-up of 11 months, a median OS was not reached.

Myelosuppression with triplet regimens incorporating FLT3 inhibitors is notable and is managed by attenuating the FLT3i dose (gilteritinib to 80 mg/d, quizartinib to 30 mg/d); the use of early disease assessment on cycle 1, day 14, with treatment interruption if blasts are fewer than 5% or marrow aplasia is observed; and the use of a 7-day course of venetoclax from cycle 2 onward.24 With this approach, rates febrile neutropenia and infection of grade 3 or higher were similar to HMA-VEN doublets (33% and 53%, respectively). A randomized dose-ranging and expansion study to identify the optimal dose of the GILT triplet combination (NCT05520567) is ongoing, and a randomized study comparing GILT-C-DEC-VEN to C-DEC-VEN is planned in the upcoming MyeloMatch Initiative.

VEN-GILT and AZA-VEN-GILT remain salvage options for patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) FLT3-ITD-mutated AML, though with decreased efficacy if previously treated with HMA-VEN.24,45 In all patients with R/R AML, the composite CR rate (CR + CRi + CRp + morphologic leukemia-free state) to VEN-GILT and AZA-VEN-GILT was 75% and 68%, and the median OS was 10 and 5.8 months, respectively. Reduction of FLT3 transcript levels to less than 10−4 and less than 10−5 occurred in 20% and 27% of patients with R/R AML treated with VEN-GILT or AZA-VEN-GILT, respectively.

Serial monitoring of FLT3-ITD transcripts and the use of a FLT3 inhibitor in select patients with molecular persistence or rising MRD on HMA-VEN regimens may also preempt overt morphologic relapse and further improve survival, either as a bridge to HCT or in patients who remain MRD positive before or following HCT.47,48

K/NRAS-mutated or monocytic AML

Mutations in N/KRAS genes correspond with inferior response and survival following HMA-VEN treatment (Table 1).11,21,49 Monocytic myeloid differentiation, particularly in the absence of co-occurring favorable mutations such as NPM1, also confers venetoclax resistance, often coexisting with mutations in active signaling genes.17,50 For this molecular subgroup, the incorporation of nucleoside analogs including fludarabine or cladribine (CLAD) is an increasingly recognized alternative to standard HMA-VEN combinations.25,50

The triplet nucleoside regimen alternating cycles of CLAD, low-dose cytarabine (LDAC), and AZA-VEN resulted in CR/CRi rates of 93%, including 84% who were MRD negative measured using MFC (Table 2).25 After a follow-up of 22 months, the estimated 24-month OS rate was 72.9%. While inclusive of a younger patient population compared to VIALE-A (median age, 68 years) with high HCT utilization (34% proceeded to HCT in the first CR), these outcomes are similar to those observed in an IC-eligible population. A post-hoc analysis comparing CLAD/LDAC/VEN with HMA-VEN demonstrated a CR/CRi rate of 83% vs 45% in patients with N/KRAS-mutated AML.51 Updated phase 2 data demonstrated a median OS of 25 months for patients with intermediate- benefit AML based on the mPRS score, suggesting this regimen may improve survival compared to HMA-VEN in patients with active signaling mutations.52 A prospective study evaluating the efficacy of this combination specifically in active signaling and/or monocytic AML is planned (NCT06504459).

NPM1-mutated and KMT2A-rearranged AML

NPM1-mutated AML is characterized by cytarabine sensitivity, and thus older patients with NPM1-mutated AML historically experienced inferior outcomes compared to younger patients able to receive IC.9,11,19,53 However, two lower-intensity treatment options, LDAC-VEN (VIALE-C) and AZA-VEN (VIALE-A), resulted in CR/CRi rates of 78% and 66.7%, with the latter regimen associated with an MRD-negative (MFC) CR/CRi rate of 88%.9,54 Reported 2-year OS from a pooled analysis of patients receiving either LDAC-VEN or AZA-VEN was 72%, confirming the important role of venetoclax in older IC-ineligible patients with NPM1- mutated AML (Table 1).11

As highlighted throughout this text, VEN-based regimens can effectively eradicate MRD, which has a demonstrable prognostic impact in patients receiving lower-intensity treatment.27,28,55 Using MRD-MFC (level of sensitivity, 10−3), 88% of evaluable patients enrolled in VIALE-A with NPM1-mutated AML attained MRD-negative CR/CRi; similarly high MRD-negative CR/CRi rates (58%-63%) using NPM1 MRD assays measured via quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) (level of sensitivity, 10−4) have been reported.22,27,28 Undetectable MRD-MFC from bone marrow samples (from all included patients) following AZA-VEN corresponded with an estimated 12-month OS of 94%, while undetectable NPM1 MRD RT-qPCR following 4 cycles of either AZA-VEN or LDAC-VEN therapy corresponded to a 2-year OS of 84%.27,28 Of note, MRD responses with lower-intensity therapy may evolve slowly, with some patients becoming undetectable only after 6-7 cycles of therapy.27,28

In venetoclax-naïve patients with persistent MRD-positive NPM1-mutated AML, MRD-targeted therapy using LDAC-VEN resulted in molecular clearance in 55% of patients with molecular relapse (defined as >1 log10 rise in MRD) and 75% of patients with oligoblastic relapse (ie, 5%-15% bone marrow myeloblasts).55 The corresponding 2-year OS of 63% compares favorably to reported outcomes following IC in this setting (2-year OS, 29%-61%).55

Treatment-free remissions may even be a reality for select patients in this NPM1-mutated molecular subgroup who attain MRD negativity.28,56 After a median follow-up of 15 months after treatment cessation, treatment-free remissions in patients who had undetectable NPM1 MRD RT-qPCR from bone marrow samples was ongoing in 88%.28 Similar treatment-free remissions have been described for patients with co-occurring or isolated IDH2 mutations.56

The inhibition of the menin-KMT2A axis represents an emergent class of therapeutics with activity in NPM1-mutated and KMT2A-rearranged (KMT2Ar) AML, molecular subclasses driven by shared HOX and MEIS1 gene upregulation.11,26

In patients with R/R NPM1-mutated or KMT2Ar acute leukemias (60% of whom received prior venetoclax), revumenib treatment resulted in a CR plus CR with partial hematologic recovery rate of 30% (NPM1 mutated, 21%; KMT2Ar, 33%).26 Notably high rates of undetectable MRD-MFC were observed (78%) in responding patients, although responses to menin inhibitors are generally short-lived with a median DOR of 6 months, with emergent mutations in the MEN1 gene as one identified resistance mechanism limiting single-agent activity.26,57 Combining menin inhibitors with HMA-VEN in the frontline or RR setting may represent more effective treatment strategies (Table 2). While survival follow-up is premature, frontline therapy with AZA-VEN- revumenib resulted in an impressive composite CR rate of 100% (N = 13/13), suggesting this regimen is highly active in NPM1 or KMT2A-rearranged AML.58

MRD-directed therapies

The adverse prognostic impact of persistent MRD in AML provides a further rationale for the development of MRD-directed therapies, which can prevent morphologic relapse and improve survival.27,28,44,55 The ongoing INTERCEPT and MyeloMatch studies are investigating targeted MRD-directed interventions, while the development of antibody-based therapies such as bispecific CD3-CD123 T-cell engagers and CD123-targeting antibody-drug conjugates continues in this area.59–61

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

IVO-AZA was selected as frontline therapy. A repeat bone marrow examination following 2 treatment cycles demonstrated a complete morphologic response, and after 4 cycles no IDH1 mutation was detectable. The patient remains in an MRD-negative remission to date.

Conclusion

AML treatment has evolved tremendously since the binary options of hypomethylating agent monotherapy vs induction chemotherapy. These emerging therapeutic options, along with the preemptive treatment of MRD, rationally designed treatment combinations and sequencing approaches, and increasingly individualized prognostication tools, will assuredly further improve the treatment and survival of older adults with AML.

Acknowledgments

Curtis A. Lachowiez is supported through an Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute KL2 award (KL2TR002370). Courtney D. DiNardo is supported by the LLS Scholar in Clinical Research Award.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Curtis A. Lachowiez: consultancy: AbbVie, Rigel, Servier, Bristol Myers Squibb, Syndax, COTA Healthcare; advisory board: AbbVie, Rigel, Servier, Bristol Myers Squibb, Syndax, COTA Healthcare.

Courtney D. DiNardo: research funding: AbbVie, Astex, Beigene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Foghorn, ImmuneOnc, Jazz, Rigel, Schrodinger, Servier; consultancy: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, GenMab, GSK, Immunogen, Notable Labs, Rigel, Schrodinger, Servier; advisory board: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, GenMab, GSK, Immunogen, Notable Labs, Rigel, Schrodinger, Servier.

Off-label drug use

Curtis A. Lachowiez: Off-label drug use will be discussed throughout the article (CAL and CDD).

Courtney D. DiNardo: Off-label drug use will be discussed throughout the article (CAL and CDD).