Abstract

The treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has been transformed over the past decade based on a better understanding of disease biology, especially regarding molecular genetic drivers and relevant signaling pathways. Agents focusing on B-cell receptor (in particular Bruton tyrosine kinase [BTK]) and apoptosis (BCL2) targets have replaced chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) as the treatment standard. BTK and BCL2 inhibitor−based therapy has consistently shown prolonged progression-free survival and in some instances even increased overall survival against CIT in frontline phase 3 trials. This improvement is particularly pronounced in high-risk CLL subgroups defined by unmutated IGHV, deletion 17p (17p−), and/or the mutation of TP53, making CIT in these subgroups essentially obsolete. Despite remarkable advances, these markers also retain a differential prognostic and predictive impact in the context of targeted therapies, mandating risk-stratification in frontline management. Furthermore, BTK- and BCL2-targeting agents differ in their adverse event profiles, requiring adjustment of treatment choice based on patient characteristics such as coexisting conditions, comedications, and delivery-of-care aspects.

Learning Objectives

Review the stratification factors for CLL

Evaluate the treatment options for CLL

CLINICAL CASE

A 72-year-old man with untreated CLL presents with worsening fatigue. Early-stage CLL had been diagnosed 3 years earlier in a health checkup, and at that time he was free of complaints, with an unremarkable physical examination and a normal hemoglobin level and platelet count. Now there is progressive lymphocytosis (89 × 103/µL), anemia (10.7 g/dL), and thrombocytopenia (104 × 103/µL). On physical examination there is ubiquitous lymphadenopathy up to 4 cm in diameter, and the spleen is palpable 5 cm below the costal margin upon inspiration. CLL prognostic marker assessment shows unmutated IGHV (uIGHV) and 13q deletion, with the absence of 17p− and no TP53 mutation (TP53mut). Past medical history is notable for stent placement for unstable angina due to 2-vessel coronary artery disease 2 years ago, arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Current medication includes aspirin, bisoprolol, candesartan, and atorvastatin as well as antiobstructive dual bronchodilator therapy with well-controlled blood pressure and pulmonary function. Regular cardiology assessments are unremarkable with sinus rhythm and normal left ventricular function. His current creatinine clearance is 63 mL/min, the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score is 6, and he lives with his wife of similar fitness in a suburban area with a 30-minute drive to his practice-based oncologist. Because of worsening fatigue, the development of anemia and thrombocytopenia, and progressive organomegaly, there is an indication for treatment according to International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (iwCLL) criteria, and the patient is asking for your recommendation.

Overview of stratification factors and frontline treatment options

Similar to our case, the vast majority of patients with CLL today are diagnosed with asymptomatic, early-stage disease, for which the standard of care is watch and wait.1,2 Based on data from interventional trials, there is no role for treatment initiation in this disease phase, and therapy should only be started when the iwCLL criteria for “active disease” are met.1-3 Pretreatment evaluation in addition to a thorough history, physical examination, and laboratory analyses according to the iwCLL guidelines includes an assessment of prognostic markers, most importantly chromosome 17p by fluorescence in situ hybridization, TP53 by sequencing, and IGHV mutational status.1,2 Multiple additional markers, such as ß2-MG, TK, CD38, CD49, ZAP-70, telomere length, metaphase chromosome karyotype, and specific gene mutations (eg, NOTCH1, SF3B1, ATM, NFKBIE, BIRC3) have been found to be of prognostic significance, but their role is less well established in the context of targeted therapy, and further evaluation is needed in clinical trials before they can be used to guide routine management. Complex karyotype (classically 3 or more chromosomal aberrations detected by metaphase chromosome banding) is strongly associated with 17p− and/or TP53mut and is currently not used for stratification between Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) or BCL2 inhibitor–based treatment due to unclear cut points (3 or 5 aberrations), less consistent associations with outcome, and no clear differential efficacy with targeted therapy options. Measurable residual disease (MRD) is of strong prognostic value with some treatments. However, there is no direct evidence for the superiority of MRD-guided therapy over fixed-duration targeted treatment regimens; therefore, MRD is not currently the standard for management decisions in general practice outside clinical trials. Further assessments such as positron emission tomography- computed tomography and lymph node or bone marrow biopsy are reserved for particular situations such as severe constitutional symptoms, marked lactate dehydrogenase elevation (suggestive of Richter transformation), or unclear cytopenia.1,2

There is no single standard frontline treatment, and stratification depends on genetic risk markers, patient comorbidities, comedications, preference, and logistics. Based on multicenter phase 3 trials against CIT, the preferred licensed treatment options are either continuous therapy with a BTK inhibitor such as acalabrutinib,4-7 ibrutinib,8-16 or zanubrutinib,17-20 the first 2 optionally combined with 6 cycles of obinutuzumab and differentially discussed below, or fixed-duration venetoclax for 1 year plus 6 cycles of obinutuzumab,21-27 or fixed-duration ibrutinib plus venetoclax (combined for 12 months after 3-month ibrutinib lead-in, currently licensed only by the European Medicines Agency but not the US Food and Drug Administration).28-33 Both venetoclax plus obinutuzumab and venetoclax plus ibrutinib (or potentially any BCL2 inhibitor combined with other agents) are termed “BCL2 inhibitor– based” finite-duration regimens for the sake of clarity.

Acalabrutinib and acalabrutinib plus obinutuzumab were evaluated in ELEVATE-TN against chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab,4-6 zanubrutinib in SEQUOIA against bendamustine plus rituximab,17,18 and ibrutinib (with or without CD20 antibody) in several trials (E1912, FLAIR, ALLIANCE A041202, iLLUMINATE, RESONATE-2) against various CIT regimens.8-16 Venetoclax plus obinutuzumab was evaluated in 2 trials, CLL14 against chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab and in GAIA/CLL13 with 4 arms (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab/bendamustine, rituximab, or venetoclax plus rituximab, or venetoclax plus obinutuzumab, venetoclax plus ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab).21-27 Ibrutinib plus or venetoclax was evaluated in 2 trials against CIT, GLOW (15 months fixed duration against chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab), and FLAIR (time-limited MRD guided against fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab).30-33

In aggregate, all these phase 3 trials consistently showed a clinically meaningful and statistically significant progression- free survival (PFS) advantage for continuous BTK or finite- duration BCL2 inhibitor–based frontline therapy over CIT, and the benefit was most pronounced in subgroups with uIGHV and 17p− and/or TP53mut.4-33 Also, targeted treatments in general showed numerically better PFS in mutated IGHV (mIGHV) CLL and also OS, even reaching statistical significance for overall survival (OS) superiority in some trials (RESONATE-2, ECOG1912, ELEVATE-TN, GLOW, FLAIR).5,6,9,13,30-33 Adding ibrutinib to venetoclax plus obinutuzumab and adding obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib or ibrutinib improved efficacy at the cost of increased toxicity.5,6,15,16,25,27 The addition of rituximab to ibrutinib did not increase PFS or OS compared to ibrutinib alone, and adding rituximab to venetoclax was less efficacious compared to adding obinutzumab.11,12,25,27 Treatment-free survival (TFS, defined as time to the next therapy or death) was significantly improved with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab (CLL14, 65.2% at 6 years; GAIA/CLL13, 87.1% at 4 years) and with ibrutinib plus venetoclax (GLOW: 75.6% at 4.5 years) over CIT.24,27,32 The GLOW study showed different survival patterns between treatments. The ibrutinib plus venetoclax group had more deaths during treatment (7 vs 2) but fewer after treatment (12 vs 37) compared to chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab.32 MRD-guided ibrutinib plus venetoclax treatment as used in FLAIR is not approved and may help to optimize outcome in the future, but it appears likely that additional parameters such as IGHV must be taken into account to achieve this.28-33 However, the PFS and OS differences observed within 1 to 2 years of treatment in FLAIR suggest beneficial outcomes with a 15-month ibrutinib plus venetoclax regimen in young patients.33 The efficacy of targeted treatment regimens from phase 3 trials sorted by agent/regimen is summarized in Table 1. Importantly, there are marked differences in outcome with the same treatment in genetic subgroups and also between trials enrolling fit and/or young patients (ECOG1912, CLL13, FLAIR) compared to unfit and/or older patients (RESONATE-2, iLLUMINATE, ALLIANCE, ELEVATE-TN, SEQUOIA, CLL14, GLOW) patients.

Overview of characteristics and outcomes for PFS and OS (rates at 36, 48, and 72 months) for targeted therapy groups from CLL frontline phase 3 trials for all patients and for genetic subgroups (uIGHV, mIGHV, 17p−/TP53mut)

| Trial treatment no. of patients . | Characteristics (median, if not indicated otherwise) . | Estimate at month . | PFS rate (%) . | OS rate (%) . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients . | uIGHV . | mIGHV . | 17p− and/or TP53mut . | All patients . | uIGHV . | mIGHV . | 17p− and/or TP53mut . | ||||

| RESONATE-2 Ibr n = 136 | FU: 60 | Age: 73 | 36 | 82a | 82a | 83a | 88a | ||||

| CIRS > 6: 31% | 48 | 74a | 75a | 80a | 86a | ||||||

| CrCl < 60 mL/min: 44% | 72 | 62a | 62a | 67a | 77a | ||||||

| iLLUMINATE Obi-Ibr n = 113 | FU: 46 | Age: 70 | 36 | 79 | 70a | 90a | 86 | ||||

| CIRS: 4 | CrCl: 72 | 48 | 74 | 67 | 89 | 82 | |||||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| ALLIANCE Ibr n = 182 | FU: 55 | Age: 71 | 36 | 82 | 82 | 84 | 78 | 89 | 89 | 86 | 83 |

| CrCl: 69 | 48 | 76 | 73 | 84 | 73 | 85 | 85 | 86 | 83 | ||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| ALLIANCE R-Ibr n = 182 | FU: 55 | Age: 71 | 36 | 81 | 70 | 83 | 80 | 89 | 84 | 88 | 85 |

| CrCl: 67 | 48 | 76 | 66 | 78 | 80 | 86 | 82 | 84 | 81 | ||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| ECOG 1912 R-Ibr n = 354 | FU: 71 | Age: 58 | 36 | 89 | 90 | 88 | 85b | 99 | 99 | 97 | 96b |

| CrCl: 95 | 48 | 83 | 83 | 87 | 77b | 97 | 98 | 97 | 92b | ||

| 72 | 72 | 68 | 77 | 51b | 93 | 93 | 92 | 87b | |||

| FLAIR R-Ibr n = 384 | FU: 53 | Age: 63 | 36 | 90 | 88a | 92a | 95 | ||||

| CrCl: 79 | 48 | 86 | 88 | 92 | 67b | 92 | |||||

| 72 | 67 | 89 | |||||||||

| ELEVATE-TN Acala n = 179 | FU: 75 | Age: 70 | 36 | 84 | 92 | ||||||

| CrCl: 75 | 48 | 78 | 77 | 81 | 76 | 88 | |||||

| 72 | 62 | 60 | 56 | 76 | 76 | 72 | |||||

| ELEVATE-TN Obi-Acala n = 179 | FU: 75 | Age: 70 | 36 | 92 | 95 | ||||||

| CrCl: 77 | 48 | 87 | 86 | 89 | 75 | 93 | |||||

| 72 | 78 | 75 | 56 | 84 | 84 | 68 | |||||

| SEQUOIA Zanu n = 241 | FU: 44 | Age: 70 | 36 | 84 | 82 | 87 | 91 | 89 | 93 | ||

| 48 | 79 | 72 | 86 | 88 | 85 | 93 | |||||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| CLL14 Obi-Ven n = 216 | FU: 76 | Age: 72 | 36 | 82 | 82 | 86 | 63 | 89 | 89 | 91 | 80 |

| CIRS: 9 | CrCl: 65.2 | 48 | 74 | 69 | 85 | 54 | 85 | 83 | 89 | 72 | |

| 72 | 53 | 43 | 72 | 22 | 79 | 78 | 82 | 60 | |||

| CLL13 Obi-Ven n = 229 | FU: 51 | Age: 62 | 36 | 89 | 84 | 94 | n.a. | 97 | 96 | 97 | n.a. |

| CIRS: 2 | CrCl: 86.3 | 48 | 82 | 74 | 92 | n.a. | 95 | 94 | 97 | n.a. | |

| 72 | |||||||||||

| GLOW Ibr-Ven n = 106 | FU: 57 | Age: 71 | 36 | 79 | 72a | 90a | 90a | ||||

| CIRS: 9 | CrCl: 66.5 | 48 | 70 | 63a | 90a | 86a | |||||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| FLAIR Ibr-Ven n = 260 | FU: 44 | Age: 62 | 36 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 96 | ||||

| CrCl: 83 | 48 | 94 | 95 | ||||||||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| Trial treatment no. of patients . | Characteristics (median, if not indicated otherwise) . | Estimate at month . | PFS rate (%) . | OS rate (%) . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients . | uIGHV . | mIGHV . | 17p− and/or TP53mut . | All patients . | uIGHV . | mIGHV . | 17p− and/or TP53mut . | ||||

| RESONATE-2 Ibr n = 136 | FU: 60 | Age: 73 | 36 | 82a | 82a | 83a | 88a | ||||

| CIRS > 6: 31% | 48 | 74a | 75a | 80a | 86a | ||||||

| CrCl < 60 mL/min: 44% | 72 | 62a | 62a | 67a | 77a | ||||||

| iLLUMINATE Obi-Ibr n = 113 | FU: 46 | Age: 70 | 36 | 79 | 70a | 90a | 86 | ||||

| CIRS: 4 | CrCl: 72 | 48 | 74 | 67 | 89 | 82 | |||||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| ALLIANCE Ibr n = 182 | FU: 55 | Age: 71 | 36 | 82 | 82 | 84 | 78 | 89 | 89 | 86 | 83 |

| CrCl: 69 | 48 | 76 | 73 | 84 | 73 | 85 | 85 | 86 | 83 | ||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| ALLIANCE R-Ibr n = 182 | FU: 55 | Age: 71 | 36 | 81 | 70 | 83 | 80 | 89 | 84 | 88 | 85 |

| CrCl: 67 | 48 | 76 | 66 | 78 | 80 | 86 | 82 | 84 | 81 | ||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| ECOG 1912 R-Ibr n = 354 | FU: 71 | Age: 58 | 36 | 89 | 90 | 88 | 85b | 99 | 99 | 97 | 96b |

| CrCl: 95 | 48 | 83 | 83 | 87 | 77b | 97 | 98 | 97 | 92b | ||

| 72 | 72 | 68 | 77 | 51b | 93 | 93 | 92 | 87b | |||

| FLAIR R-Ibr n = 384 | FU: 53 | Age: 63 | 36 | 90 | 88a | 92a | 95 | ||||

| CrCl: 79 | 48 | 86 | 88 | 92 | 67b | 92 | |||||

| 72 | 67 | 89 | |||||||||

| ELEVATE-TN Acala n = 179 | FU: 75 | Age: 70 | 36 | 84 | 92 | ||||||

| CrCl: 75 | 48 | 78 | 77 | 81 | 76 | 88 | |||||

| 72 | 62 | 60 | 56 | 76 | 76 | 72 | |||||

| ELEVATE-TN Obi-Acala n = 179 | FU: 75 | Age: 70 | 36 | 92 | 95 | ||||||

| CrCl: 77 | 48 | 87 | 86 | 89 | 75 | 93 | |||||

| 72 | 78 | 75 | 56 | 84 | 84 | 68 | |||||

| SEQUOIA Zanu n = 241 | FU: 44 | Age: 70 | 36 | 84 | 82 | 87 | 91 | 89 | 93 | ||

| 48 | 79 | 72 | 86 | 88 | 85 | 93 | |||||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| CLL14 Obi-Ven n = 216 | FU: 76 | Age: 72 | 36 | 82 | 82 | 86 | 63 | 89 | 89 | 91 | 80 |

| CIRS: 9 | CrCl: 65.2 | 48 | 74 | 69 | 85 | 54 | 85 | 83 | 89 | 72 | |

| 72 | 53 | 43 | 72 | 22 | 79 | 78 | 82 | 60 | |||

| CLL13 Obi-Ven n = 229 | FU: 51 | Age: 62 | 36 | 89 | 84 | 94 | n.a. | 97 | 96 | 97 | n.a. |

| CIRS: 2 | CrCl: 86.3 | 48 | 82 | 74 | 92 | n.a. | 95 | 94 | 97 | n.a. | |

| 72 | |||||||||||

| GLOW Ibr-Ven n = 106 | FU: 57 | Age: 71 | 36 | 79 | 72a | 90a | 90a | ||||

| CIRS: 9 | CrCl: 66.5 | 48 | 70 | 63a | 90a | 86a | |||||

| 72 | |||||||||||

| FLAIR Ibr-Ven n = 260 | FU: 44 | Age: 62 | 36 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 96 | ||||

| CrCl: 83 | 48 | 94 | 95 | ||||||||

| 72 | |||||||||||

Estimates from survival curve.

Sole TP53 mutation; empty fields = data not available.

Acala, acalabrutinib; Age, age in years; CrCl, creatinine clearance in mL/min; FU, median follow-up time in months; Ibr, ibrutinib; n.a., not applicable as 17p− and TP53mut were excluded; Obi, obinutuzumab; R, rituximab; Ven, venetoclax; Zanu, zanubrutinib.

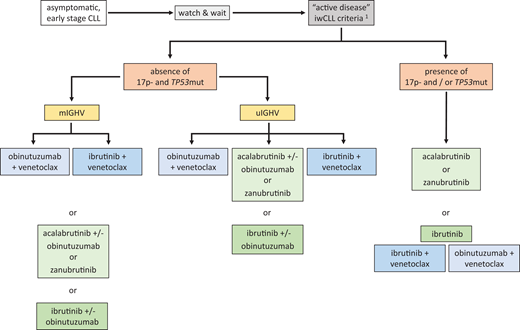

In summary, targeted therapies are preferred over CIT due to superior efficacy, in particular for uIGHV and 17p− and/or TP53mut CLL, combined with favorable tolerability. CIT may be considered only in exceptional settings, also based on regional access and reimbursement policies, and the regimen depends on the clinical fitness and age of the patient. Of note, there are no direct head-to-head data available comparing the standard continuous BTK inhibitor and fixed-duration BCL2 inhibitor− based treatment options. Therefore, recommendations for the stratification of individual patients must be based on cross-trial comparisons, and there is latitude for the influence of multiple disease characteristics and patient-related factors. A suggested frontline treatment stratification algorithm based on genetic markers is given in Figure 1. Preferred treatment options are prioritized from top to bottom, and the choice is further influenced by patient characteristics and preference.

Suggested frontline treatment algorithm according to genetic CLL subgroups. Treatment is only indicated when iwCLL criteria of “active disease” are met.1 Stratification is by 17p−/TP53mut (17p−: deletion 17p by fluorescence in situ hybridization; TP53mut: TP53 mutation by sequencing) and IGHV mutation status. Treatment options are prioritized from top (preferred options) to bottom (alternatives). The principal stratification by genetic factors must be put into context with patient comorbidities, comedications, preferences, and delivery-of-care aspects that may modify the preferred treatment choice.

Suggested frontline treatment algorithm according to genetic CLL subgroups. Treatment is only indicated when iwCLL criteria of “active disease” are met.1 Stratification is by 17p−/TP53mut (17p−: deletion 17p by fluorescence in situ hybridization; TP53mut: TP53 mutation by sequencing) and IGHV mutation status. Treatment options are prioritized from top (preferred options) to bottom (alternatives). The principal stratification by genetic factors must be put into context with patient comorbidities, comedications, preferences, and delivery-of-care aspects that may modify the preferred treatment choice.

Treatment decisions based on patient characteristics, comedications, toxicity, and logistics

Adverse events with BTK and BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy

In general, treatment with BTK and BCL2 inhibitors is better tolerated than CIT, especially regarding hematologic toxicity and severe infections, but specific logistic requirements and adverse events (AEs) for each drug are relevant for stratifying patients based on their individual coexisting conditions.

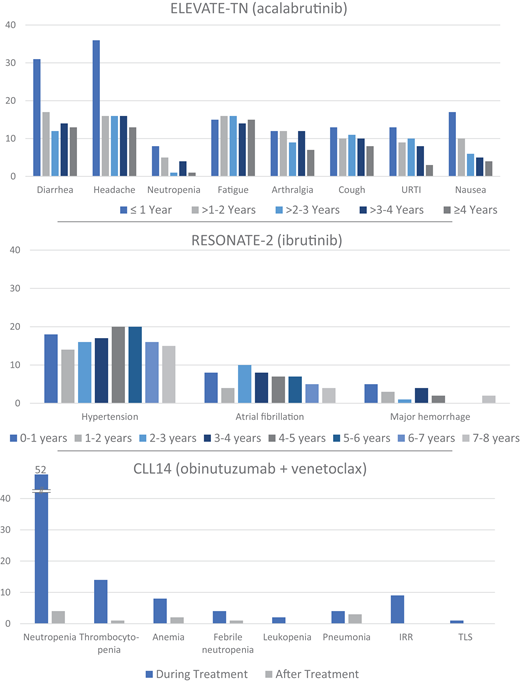

With BTK inhibitors the most common AEs across all trials were infection, bleeding, diarrhea, arthralgia, myalgia, and headache.4-19 AEs of special interest included cardiovascular events, especially atrial fibrillation and hypertension. AEs are most frequent during the first months of therapy but accumulate over the years with continuous treatment (Figure 2).6,9,11,13,16,18 While most data are available with ibrutinib, studies in the relapsed setting showed that acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib are at least as effective and better tolerated: in the ELEVATE-RR trial, acalabrutinib showed similar efficacy as ibrutinib and overall better tolerability (ie, a reduction of all class-associated AEs),7 whereas in the ALPINE trial, zanubrutinib appeared more effective than ibrutinib with a narrower improvement in tolerability (ie, less cardiac toxicity),19 making acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib the preferred options. This applies particularly to patients with relevant comorbidity (ie, significant cardiovascular disease).

Graphical compilation of AEs over time with continuous BTK and fixed-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy from phase 3 frontline CLL trials in older/unfit patients with mature follow-up. The most frequent AEs of any grade occurring on an annual basis for acalabrutinib and of clinical interest for ibrutinib are shown. For obinutuzumab plus venetoclax, the most frequent AEs grade 3 and higher are shown during or after therapy. URTI, upper respiratory tract infection. Data modified with permission from Sharman et al,5 Barr et al,9 and Al-Sawaf et al.23

Graphical compilation of AEs over time with continuous BTK and fixed-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy from phase 3 frontline CLL trials in older/unfit patients with mature follow-up. The most frequent AEs of any grade occurring on an annual basis for acalabrutinib and of clinical interest for ibrutinib are shown. For obinutuzumab plus venetoclax, the most frequent AEs grade 3 and higher are shown during or after therapy. URTI, upper respiratory tract infection. Data modified with permission from Sharman et al,5 Barr et al,9 and Al-Sawaf et al.23

With obinutuzumab plus venetoclax, the most common toxicities were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, diarrhea, nausea, infection, and fatigue.21-27 The regimen requires a ramp-up schedule, prophylaxis, and monitoring to avoid potentially life-threatening tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) during venetoclax initiation and premedication to manage infusion-related reactions (IRRs) during the first cycles of obinutuzumab. With this, TLS was rare in clinical trials and should be avoidable when risk-based logistic precautions as per the prescription information on the product label are followed.21,25 Following the complex treatment initiation and a considerable rate of high-grade AEs initially on therapy, there is a lack of treatment-related AEs in the years off treatment (Figure 2).

With ibrutinib plus venetoclax, the most common AEs were neutropenia, diarrhea, infection, hypertension, and cardiac events.28-33 There were increased early, mostly cardiac or sudden deaths in the GLOW trial among older patients with high CIRS scores and cardiovascular comorbidity,30-32 while this was not observed among fit and/or young patients in FLAIR and phase 2 data.28,29,33 The 3-month ibrutinib lead-in prior to the venetoclax ramp-up appeared to decrease TLS risk, which, together with the absence of obinutuzumab-related IRRs, may enable easier management of treatment initiation. Initially, there is the AE risk of both agents over a limited period of time, which is followed by the absence of drug-related AEs during the time off treatment.28-33

Consideration of comorbidities, comedications, logistical aspects, and patient preference

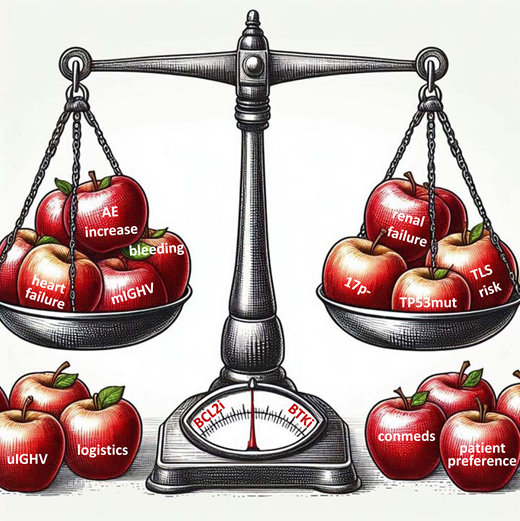

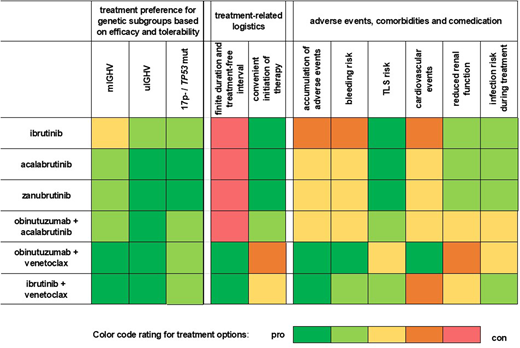

CLL therapy options differ significantly in AEs and the burden of administration. Therefore, comorbidities, comedications, logistics, and patient preferences substantially influence the choice based on multiple aspects (Figure 3). Also, both BTK and BCL2 inhibitors are CYP3A4 substrates and are associated with multiple drug interactions, potentially necessitating comedication adjustment per prescription information.

Heat map of treatment options in rows and stratification factors in columns (genetic risk markers, therapy logistics, AE profiles, patient characteristics, and delivery-of-care aspects) weighed for pros and cons regarding treatment choice on a 5-tier scale (green most favorable, red most unfavorable) for typical patients with CLL (older adults and with comorbidities). Overall treatment preferences (3 columns on the left) are based on efficacy in genetic subgroups and modified based on therapy logistics (2 middle columns), AE profiles, comorbidities, and comedication (6 columns on the right).

Heat map of treatment options in rows and stratification factors in columns (genetic risk markers, therapy logistics, AE profiles, patient characteristics, and delivery-of-care aspects) weighed for pros and cons regarding treatment choice on a 5-tier scale (green most favorable, red most unfavorable) for typical patients with CLL (older adults and with comorbidities). Overall treatment preferences (3 columns on the left) are based on efficacy in genetic subgroups and modified based on therapy logistics (2 middle columns), AE profiles, comorbidities, and comedication (6 columns on the right).

As compared to CIT, the overall fitness and age of patients are of reduced relevance with targeted therapy, and therefore comorbidity indices or scores are not used for decisions. Rather, specific coexisting conditions, comedications and logistical aspects are used to guide treatment choices.

BTK inhibitors are less preferred in patients with cardiovascular disorders, hypertension, and/or a high risk for bleeding (eg, a history of major bleeding).6,9,11,13,16,18 Drug holds are recommended to mitigate the risk of perioperative hemorrhage. BTK inhibitors should be used with caution together with anticoagulants, especially when those are combined with agents interfering with platelet function (eg, aspirin, clopidogrel). Logistically, therapy initiation is convenient, but AEs accumulate over time during continuous BTK inhibitor therapy, and treatment adherence over years may be challenging (Figure 2).6,9,11,13,16,18 The addition of obinutuzumab enhances efficacy but also increases the risk of neutropenia and infections. Hence, fitness and risk of infections should be evaluated before adding obinutuzumab to BTK inhibitor–based therapy, which may be preferred in young and/or fit patients.5,6,15,16

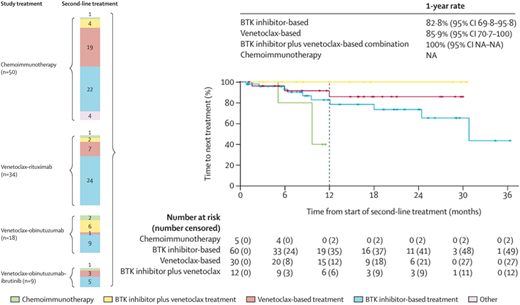

Venetoclax plus obinutuzumab is usually avoided in patients with severe kidney disease and less preferred together with nephrotoxic drugs.21-26 High tumor burden increases the risk for TLS, and prophylactic procedures are essential for safe treatment initiation. Initial obinutuzumab mitigates the TLS risk for the venetoclax ramp-up but is itself associated with TLS risk and IRRs, potentially requiring intense management.25 Logistically, treatment initiation is inconvenient, with frequent visits or inpatient admissions, especially with high TLS risk, but fixed-duration venetoclax plus obinutuzumab offers durable treatment-free intervals with the absence of AE burden and the opportunity for venetoclax-based retreatment (Figure 4).24,27,34-36

Summary of initial therapy, retreatment, and its outcome in the CLL13/GAIA trial. The type of frontline therapy (“study treatment”) and corresponding salvage therapy (“second-line treatment”) (color coded) with numbers of patients is shown on the left. The outcome of second-line therapy by treatment type (time to next treatment from start of second-line therapy) is shown on the right. Data modified with permission from Fürstenau et al.27

Summary of initial therapy, retreatment, and its outcome in the CLL13/GAIA trial. The type of frontline therapy (“study treatment”) and corresponding salvage therapy (“second-line treatment”) (color coded) with numbers of patients is shown on the left. The outcome of second-line therapy by treatment type (time to next treatment from start of second-line therapy) is shown on the right. Data modified with permission from Fürstenau et al.27

Ibrutinib plus venetoclax is less preferred in patients with a cardiovascular risk profile, uncontrolled hypertension, and a high risk of bleeding.28-33 Increased deaths have been observed early during treatment among unfit patients with cardiac conditions, making those worse candidates.30-32 The regimen requires TLS prophylaxis and monitoring with venetoclax ramp-up, but the risk of TLS events appears reduced after ibrutinib lead-in. Logistically, treatment initiation is reasonably convenient with reduced TLS management and no IRR. Time-limited ibrutinib plus venetoclax offers the benefit of time off therapy with the nonappearance of drug-related AEs and the potential for BTK as well as BCL2 inhibitor–based retreatment.28-33

Stratification of treatment options based on outcome in subgroups defined by genetic risk factors

Key determinants of treatment choice are the CLL-inherent genetic markers, with additional adjustment based on patient characteristics and preference (Figure 1).

The differential efficacy of targeted therapy options reported in phase 3 trials is described in Table 1 for all patients and subgroups defined by genetic markers.4-33 Of note, treatment decisions in the absence of head-to-head trials of targeted agents against each other must be based on cross-trial comparisons with marked inherent limitations. Furthermore, the comparison of data for the first PFS event does not allow a conclusion to be drawn regarding the superiority of continuous vs time-limited treatment, as retreatment with the same drug class upon progression is an option with the latter.

For 17p− and/or TP53mut, irrespective of IGHV (“very high risk”), the preferred treatment options are continuous acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib. Alternatives are continuous ibrutinib or fixed-duration venetoclax plus obinutuzumab, ibrutinib plus venetoclax, or continuous venetoclax.

Patients with 17p− and/or TP53mut CLL have traditionally faced a high risk of nonresponse, early progression, and short OS when treated with CIT.1-3 BTK and BCL2 inhibitor– based therapies have dramatically improved PFS and OS outcome over CIT, particularly in this subgroup, but there is still some prognostic impact, most clearly with time-limited venetoclax-based treatment. PFS and OS with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab were inferior in the subgroup with 17p−/ TP53mut compared to normal TP53 status,21-24 while outcome was inconsistently and to a lesser extent affected with continuous BTK inhibitor treatment (Table 1).6,11,16 Of note, data for this subgroup are limited due to exclusion in many phase 3 trials,8,9,12-14,17,18 and evidence is partly obtained from single-arm studies.37-40 The addition of obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib did not show an efficacy benefit in this subgroup in post hoc analyses.5,6 Continuous venetoclax monotherapy may be an alternative based on phase 2 data.38 Of note, this trial included only 5 patients in the frontline setting, and no conclusion can be drawn when compared to continuous BTK inhibitor treatment. Cellular therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor T cells and allogeneic transplant may be considered from the second-line treatment setting onward in 17p−/TP53mut CLL.

For uIGHV and no 17p−/TP53mut (“high risk”) CLL, the preferred treatment options are continuous acalabrutinib (with or without obinutuzumab) or zanubrutinib, fixed-duration venetoclax plus obinutuzumab, or ibrutinib plus venetoclax, and alternatives are continuous ibrutinib (with or without obinutuzumab).

Compared to CIT, patients with uIGHV CLL and normal 17p/TP53 status consistently and strongly benefit from targeted treatment options with regard to PFS and OS.4-33 Treatment choice between continuous BTK or finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy mostly depends on patient characteristics when determining the suitability of each option. Initial PFS with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab and ibrutinib plus venetoclax is somewhat reduced in uIGHV compared to mIGHV,21-33 which is evident to a lesser extent for continuous BTK inhibitor therapy (Table 1).4-16 However, the average time to second-line therapy from the initiation of front-line venetoclax plus obinutuzumab or ibrutinib plus venetoclax is long (approx. 6-7 years),21-33 and retreatment with venetoclax-based salvage therapy may lead to similar overall outcomes when comparing BCL2 and BTK inhibitor–based treatment paradigms (see below).4-36 The disadvantage of more difficult treatment initiation combined with the benefit of time off therapy with finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based regimens has to be weighed against the ease of treatment initiation combined with the accumulating burden of therapy with continuous BTK inhibitor treatment.

For mIGHV and no 17p−/TP53mut (“standard risk”) CLL, the preferred treatment options are fixed-duration venetoclax plus obinutuzumab or ibrutinib plus venetoclax, and alternatives are continuous acalabrutinib (with or without obinutuzumab) or zanubrutinib, or also ibrutinib (with or without obinutuzumab).

Patients with mIGHV CLL and normal 17p/TP53 status have more indolent disease, and the benefit of targeted therapies over CIT generally is of smaller magnitude, although the studies were not powered to detect a difference within this subgroup.4-33 Very long-term responses are seen with CIT in some patients with mIGHV CLL; however, targeted combinations are preferred over CIT due to even deeper responses (with BCL2 inhibitor–based regimens), at least noninferior PFS, and the avoidance of short- and long-term toxicities from cytotoxic agents such as second primary malignancies. Given the long PFS1 and correspondingly extended treatment-free intervals (approx. >10 years) with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab and ibrutinib plus venetoclax,21-33 finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy seems a particularly appealing approach in this subgroup, especially in light of the treatment burden of continuous BTK inhibitor therapy. Due to its slow disease kinetics, mIGHV CLL appears particularly suitable for retreatment with BCL2 inhibitor–based regimens after prolonged responses.24,27,34-36

Overall outcome depending on initial therapy and its result combined with second-line treatment

To achieve an optimal long-term outcome, it is important to consider potential salvage options already during the initial treatment choice, and scenarios differ depending on the type of therapy and mode of failure. Basically, the same agents as in frontline are available for second-line treatment, while pirtobrutinib (a noncovalent BTK inhibitor) and lisocabtagene-maraleucel (a CD19- directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy) are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for CLL after 2 prior lines, including BTK and BCL2 inhibitors.

In the instances in which treatment must be terminated due to intolerance, a switch within the BTK class (from ibrutinib to acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib) or between classes (BTK to BCL2 or BCL2 to BTK inhibitor based) is reasonable, but the latter should be reserved for cases of unmanageable toxicity to avoid the premature loss of valuable treatment options.1,2 In the majority of patients, however, failure is due to disease progression either on a continuous BTK inhibitor or after finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based treatment. Progression on acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, or ibrutinib, due to cross-resistance between these, necessitates a class switch to BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy, and therefore the first progressive disease event (PFS1) can serve as a valid time point for failure of treatment. In contrast, BCL2 inhibitor–based retreatment is possible after a treatment-free interval post initial venetoclax plus obinutuzumab or ibrutinib plus venetoclax (Figure 5), making progression after the second-line (or even higher) BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy (PFS2) a more informative end point for defining failure.

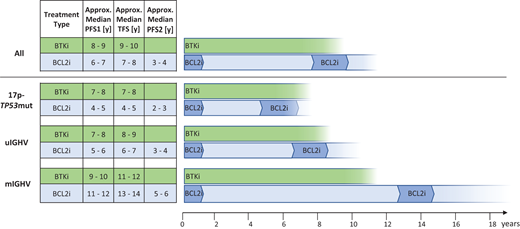

Hypothetical model of “overall time to treatment class failure” according to initial continuous BTK inhibitor (acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, ibrutinib) or finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy (obinutuzumab plus venetoclax or ibrutinib plus venetoclax) with BCL2 inhibitor–based retreatment for typical patients with CLL (older adults and with comorbidities). Estimates are given for all patients (top) and the genetic subgroups (below). PFS1: first PFS event after frontline therapy estimated from phase 3 trials in older adult/unfit patients based on data summarized in Table 1; TFS: treatment-free survival (defined as time to next therapy or death); PFS2: PFS from beginning of second-line BCL2 inhibitor–based treatment. Of note, PFS1 and TFS are estimates from phase 3 trials (Table 1) and PFS2 is an educated guess from studies of venetoclax-based salvage treatment.27,34-36,38 TFS is added on to PFS1 continuously, and median PFS2 is starting a new count for overall estimation of “time to treatment class failure” indicated by the fading of the lanes on the right.

Hypothetical model of “overall time to treatment class failure” according to initial continuous BTK inhibitor (acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, ibrutinib) or finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy (obinutuzumab plus venetoclax or ibrutinib plus venetoclax) with BCL2 inhibitor–based retreatment for typical patients with CLL (older adults and with comorbidities). Estimates are given for all patients (top) and the genetic subgroups (below). PFS1: first PFS event after frontline therapy estimated from phase 3 trials in older adult/unfit patients based on data summarized in Table 1; TFS: treatment-free survival (defined as time to next therapy or death); PFS2: PFS from beginning of second-line BCL2 inhibitor–based treatment. Of note, PFS1 and TFS are estimates from phase 3 trials (Table 1) and PFS2 is an educated guess from studies of venetoclax-based salvage treatment.27,34-36,38 TFS is added on to PFS1 continuously, and median PFS2 is starting a new count for overall estimation of “time to treatment class failure” indicated by the fading of the lanes on the right.

Despite a follow-up of up to 10 years, the median PFS1, as a surrogate for time to treatment failure and the potential need for salvage, is unreliable in currently available data, making extrapolations necessary.6,9,11,13,14,16,24,32 Estimated values for median PFS1 with continuous BTK inhibitor treatment are approximately 7 to 10 years depending on the genetic subgroup.6,9,11,13,14 Correspondingly, the projected median values for PFS1 with finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based treatment are approximately 4 to 12 years (Table 1).24,32 Upon progression on or after the initial therapy, it may take about 0 to 2 years, depending on the genetic risk group, until salvage treatment is needed. BCL2 inhibitor–based retreatment with either venetoclax plus rituximab or obinutuzumab (or other nonlicensed combinations) is likely to be effective and tolerated in these patients, though to a lesser extent compared to the first treatment (we assume a conservative 50% of PFS1 for PFS2).27,32,34-36 Specific outcome data in the second-line setting after venetoclax plus obinutuzumab or venetoclax plus ibrutinib are still limited. In general, venetoclax-based treatment of released/refractory CLL resulted in response rates in the range of 70% to 80% and an estimated median PFS of 2 to 5 years, mostly in cohorts with more than 1 prior line of therapy and enriched for early relapses as well as high-risk genetics.27,34-36,38

In the absence of reliable OS comparisons, it is clinically appropriate to equate PFS2 after second-line BCL2 inhibitor–based retreatment in those initially treated with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab or ibrutinib plus venetoclax with PFS1 in those initially treated with a BTK inhibitor, as both of these scenarios are reflections of treatment class failure. Therefore, with all caveats of such projections, it appears likely that both treatment paradigms, initial continuous BTK inhibitor6,9,11,13,14 and initial finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor-based therapy followed by retreatment,24,27,32,34-36 lead to comparable outcomes regarding the overall time to failure of 1 treatment class (Figure 5). This overall estimate may vary in favor of continuous BTK inhibitor treatment in 17p−/TP53mut CLL and in favor of finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor– based regimens in mIGHV CLL without 17p−/TP53mut. Of note, while PFS1 estimates from large phase 3 frontline trials of targeted therapy used for this model are reasonably robust, the overall outcome is a conceptual projection and not actual data.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

For our very typical CLL patient, BTK and BCL2 inhibitor–based therapy are appropriate options given the evidence of PFS and OS advantages over CIT in uIGHV CLL. Both choices are likely to lead to similar long-term efficacy, either with 1 line of continuous treatment (BTK inhibitor) or with fixed-duration therapy followed by a treatment-free interval and retreatment (BCL2 inhibitor based). Patient characteristics also show the pros and cons of either treatment option. Factors favoring continuous BTK inhibitor treatment are his high tumor load, somewhat reduced renal function, and the ease of therapy initiation, but at the cost of a continuous treatment burden. In turn, factors favoring finite-duration BCL2 inhibitor–based regimens are his cardiac comorbidity, hypertension, and prospective therapy- free years, but at the cost of a more complex treatment start. Our general preference is to enroll individuals in clinical trials evaluating targeted therapy, and our patient opted for treatment in the GCLLSG CLL17 study (continuous ibrutinib vs fixed-duration venetoclax plus ibrutinib vs fixed-duration venetoclax plus obinutuzumab). If no trial option is available, treatment choice must be based on informed decision-making with the patient, with much equipoise between BTK inhibitor– and BCL2 inhibitor–based treatment as excellent options that may shift toward either one based on the balance of genetic risk factors and patient characteristics and preferences.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients, their families, their study nurses, and their physicians for participation in the trials and donation of samples. The authors thank Michele Porro Lurà, Maneesh Tandon, Yanwen Jiang, Alexis Boulanger, Michelle Boyer, Madlaina Breuleux (Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech), Michael Moran, Brenda Chyla (AbbVie), Ariane Maes, Christoph Owenier, Christoph Tapprich, Lukas Vornholz, Mohamed Ali Kaddour, Mohamed Fouad (Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine), Dirk Weber, Andy Szeto, Remus Vezan, Mehrdad Mobasher (BeiGene), Kaoru Sakabe, Shweta Hakre, Kathryn Humphrey, and Lee Minars (AstraZeneca) for continuous support of trials and providing data details from published work. In particular, they acknowledge Jennifer Woyach (ALLIANCE A041202), Tait Shanafelt, Victoria Wang (ECOG E1912), Sean Girvan, Talha Munir, Pete Hillmen (FLAIR), Sandra Robrecht, Can Zhang, Othman Al-Sawaf, Kirsten Fischer, Moritz Fürstenau, Barbara Eichhorst, and Michael Hallek (CLL14 and CLL13/GAIA) for providing additional data and contribution to the conception of this work. The authors are also extremely thankful to Francesc Bosch, Julien Broseus, Jennifer Brown, John Byrd, Matthew Davids, Peter Dreger, Paolo Ghia, John Gribben, Billy Jebaraj, Arnon Kater, Tom Kipps, Susan O'Brien, Kanti Rai, Tadeusz Robak, Davide Rossi, Johannes Schetelig, Anna Schuh, John Seymour, Kostas Stamatopoulos, Clemens Wendtner, Bill Wierda, and Deyan Yosifov for their critical review and valuable suggestions for improvement of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB1074 subproject B1 and B2) as well as AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Gilead, Hoffmann-LaRoche, Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine, and Lilly. The authors extend their apologies to anyone whose work was not cited due to space constraints.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Eugen Tausch: honoraria, research funding, travel support, speaker fees: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen, Lilly.

Christof Schneider: honoraria, travel support, speakers fees: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, MSD.

Stephan Stilgenbauer: honoraria, research funding, travel support, speaker fees: AbbVie, Acerta, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, GSK, Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Sunesis.

Off-label drug use

Eugen Tausch: none.

Christof Schneider: none.

Stephan Stilgenbauer: none.