One of Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories for children, titled “The Elephant’s Child,” describes a young elephant with an insatiable curiosity who “asked ever so many questions.” The elephant’s child traveled to the banks of the “great grey-green greasy Limpopo river, all set about with fever trees” because he just had to know what the crocodile ate for dinner. In attempting to satisfy this curiosity, the elephant stepped too close to the river and his nose was bitten by the crocodile, who tried to drag him into the water. In the struggle that ensued, the elephant’s nose was stretched to a great length before he was able to escape. And so, the story goes, that’s how the elephant got its trunk.

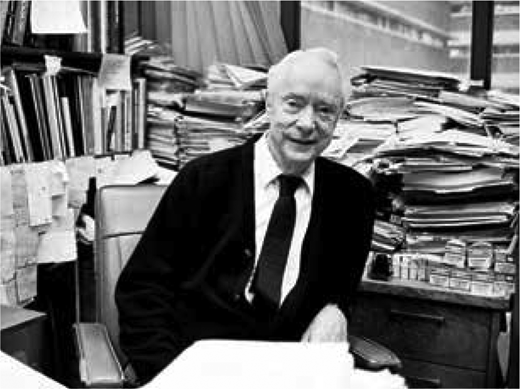

Although Dr. Earl W. Davie never had his nose bitten by a crocodile, he did share with the elephant’s child an insatiable curiosity about life. Dr. Davie, a giant in hematology, died on June 6, 2020, at the age of 92. He was best known for having described the enzymatic sequence of blood coagulation as a series of reactions in which an inactive protease precursor (zymogen) was converted to an active protease by limited proteolysis. The newly activated protease in turn would convert another zymogen to a protease, and so on until the protease thrombin is produced.

Dr. Davie grew up in the town of Alder, Washington, in the shadow of Mount Rainier, and received both his undergraduate degree in chemistry and a PhD in biochemistry at the University of Washington. During his PhD work with Dr. Hans Neurath, he published a paper demonstrating that autocatalytic activation of the zymogen trypsinogen to trypsin involved a single proteolytic step. The theme of zymogen activation by limited proteolysis would arise again in his coagulation work, and it is now appreciated that this is a widespread mechanism of protease activation in many systems, including the complement and caspase cascades. After a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard, Dr. Davie took his first faculty position at Western Reserve University in Cleveland. It was there that he met Dr. Oscar Ratnoff, a hematologist who was puzzling about why the blood of his patient Mr. Hageman failed to clot when drawn into a glass container. This encounter began a fruitful collaboration that led to the publication of their seminal paper in 1964 titled “Waterfall Sequence for Intrinsic Blood Clotting” in the journal Science. This collaboration also marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the two.

In 1966, Dr. Davie returned to Seattle to join the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Washington. He remained there until the end of his career. In the subsequent years, his laboratory undertook the task of purifying almost all the component proteins involved in blood coagulation, and characterizing the mechanistic details of their actions. This was followed by the introduction of molecular biology techniques into the field of hemostasis and thrombosis, with the subsequent cloning of cDNAs for most of the coagulation factors and determination of the sequences of their genes.

This success in understanding the biochemistry of blood clotting led Dr. Davie and his colleagues to found Zymogenetics, an early biotechnology company in Seattle that was instrumental in producing insulin, factor VIIa, thrombin, and factor XIII for human use. Dr. Davie’s patent for the factor IX cDNA was also the basis for the production of recombinant factor IX for the treatment of patients with hemophilia B.

Dr. Davie was elected to the National Academy of Sciences at age 53. He received numerous awards for his research accomplishments, including the Stratton Medal from ASH, the Robert P. Grant medal from the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Award.

As accomplished as Dr. Davie was as a scientist, his most enduring legacy may be his contributions as a teacher and mentor. Throughout his long career, he trained numerous basic scientists and clinicians, including many hematologists. Scores of his trainees have gone on to build successful careers in academia or industry and are carrying on his work of unraveling the mysteries of blood clotting and developing treatments for those with bleeding and clotting disorders.

As a mentor, Dr. Davie was never one to browbeat or intimidate his trainees. He preferred the carrot to the stick. He was always upbeat and encouraging with a very easy-going manner. This approach had the effect of motivating his students to live up to what they knew were lofty expectations.

Dr. Davie remained engaged with his former trainees long after they left the laboratory, calling often just to chat and see how things were going, or just to play a practical joke on them.

Former trainees would often visit him in the lab, regularly bringing in family members to spend time with Dr. Davie, who made them feel a part of his family. Dr. Davie welcomed these visits, as they were also occasions for him to discuss with his guests one of the many things he was thinking and learning about. The topics ranged broadly, from the migration of salmon, to volcanoes, to Mount St. Helens, to the NBA playoffs. On one occasion when Dr. López visited, Dr. Davie rushed him into his office to show him a video of an octopus “walking” along the ocean floor.

This insatiable curiosity was what made him a great scientist who contributed immensely to human knowledge and to easing the suffering of those with bleeding and clotting disorders. He never stopped asking “ever so many questions,” and humankind benefitted. His kind heart, even-temperedness, humor, and generosity allowed him to be a mentor without equal to a legion of scientists. His contributions are impossible to overstate. He will be greatly missed.

Competing Interests

Dr. López and Dr. Chung indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.