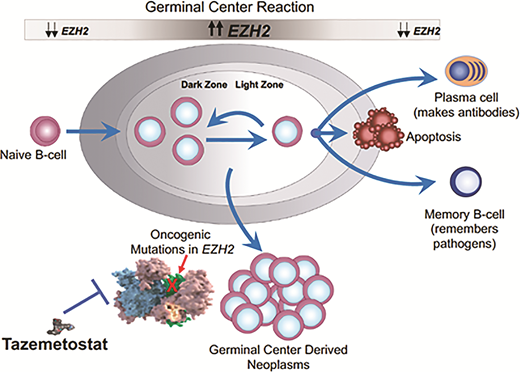

The world of oncology has dramatically evolved in the past 25 years from reliance solely on cytotoxic chemotherapy, to the introduction of molecularly targeted agents, to the current immuno-oncology wave. Along the way, many cancer types have seen the introduction of agents whose activity is highly dependent upon some predictive biomarker. However, for lymphoma, the progress has lagged. There are examples of prognostic biomarkers (activated B-cell vs. germinal center B-cell in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [DLBCL], double-hit status in DLBCL, p53 in mantle cell lymphoma), but nothing to tell us that patient X should get drug Y. Well, that appears to be changing, at least in follicular lymphoma (FL), with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of tazemetostat, an oral small molecule inhibitor of EZH2. The role of EZH2 in normal B-cell biology is depicted in Figure 1.

The role of EZH2 in germinal center biology and postulated role in lymphomagenesis. EZH2 is a histone methyltransferase and increases its activity when B cells enter the germinal center in response to antigen. The upregulated EZH2 prevents the cells from exiting the germinal center until the appropriate germinal center immune response has occurred. When the B cells are ready to differentiate into plasma cells and memory B cells, EZH2 downregulates permitting B cell exit. About 20 percent of follicular lymphomas have a gain of function mutation in EZH2, creating a permanent “locked in” state and presumably contributing to lymphoma development and proliferation.

The role of EZH2 in germinal center biology and postulated role in lymphomagenesis. EZH2 is a histone methyltransferase and increases its activity when B cells enter the germinal center in response to antigen. The upregulated EZH2 prevents the cells from exiting the germinal center until the appropriate germinal center immune response has occurred. When the B cells are ready to differentiate into plasma cells and memory B cells, EZH2 downregulates permitting B cell exit. About 20 percent of follicular lymphomas have a gain of function mutation in EZH2, creating a permanent “locked in” state and presumably contributing to lymphoma development and proliferation.

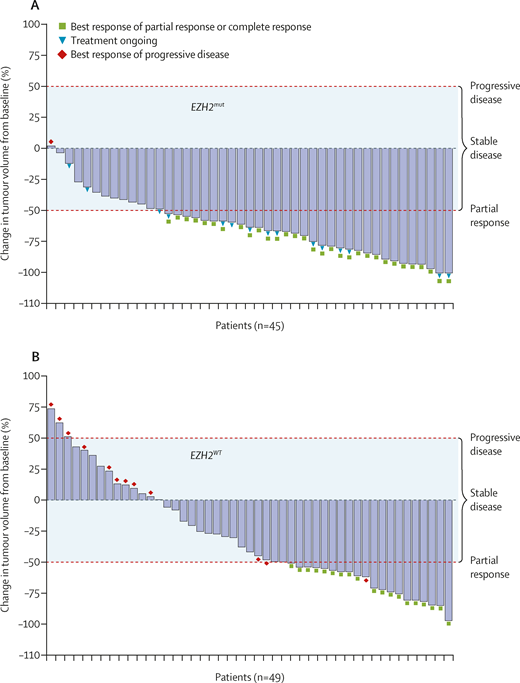

A phase II study testing tazemetostat in relapsed and refractory FL was recently published. Tazemetostat, administered at a dose of 800 mg orally twice daily, was tested in 99 patients, 45 of whom had a mutated EZH2 gene and 44 with wild-type EZH2. Treatment was administered continuously in 28-day cycles until disease progression. The adverse effect profile seemed remarkably mild. There was a low incidence of cytopenias, and gastrointestinal toxicity was distinctly uncommon. Treatment discontinuations owing to adverse events occurred in 5 percent of patients. The overall response rate was 69 percent in EZH2-mutated patients and 35 percent in EZH2 wild-type patients. The waterfall plots are depicted in Figure 2. The median response duration was 11 months in EZH2-mutated patients and 13 months in EZH2 wild-type patients.

IRC-assessed change in tumor volume from baseline. (A) Patients with EZH2mut follicular lymphoma. (B) Patients with EZH2WT follicular lymphoma. Tumor responses were not estimable, missing, or unknown in five patients in the EZH2WT cohort. Dashed red lines represent thresholds for progressive disease (≥50% increase in tumor volume) and partial response (≥50% reduction in tumor volume). The shaded area represents tumor volume changes that correspond to stable disease (<50% increase or decrease in tumor volume). IRC, independent radiology committee. Reprinted from The Lancet Oncology, Vol 21, Morschhauser F et al, Tazemetostat for patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial, 1433-1442, 2020, with permission from Elsevier.

IRC-assessed change in tumor volume from baseline. (A) Patients with EZH2mut follicular lymphoma. (B) Patients with EZH2WT follicular lymphoma. Tumor responses were not estimable, missing, or unknown in five patients in the EZH2WT cohort. Dashed red lines represent thresholds for progressive disease (≥50% increase in tumor volume) and partial response (≥50% reduction in tumor volume). The shaded area represents tumor volume changes that correspond to stable disease (<50% increase or decrease in tumor volume). IRC, independent radiology committee. Reprinted from The Lancet Oncology, Vol 21, Morschhauser F et al, Tazemetostat for patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial, 1433-1442, 2020, with permission from Elsevier.

In Brief

So, what are the implications of these data and this new agent? In 2021, most patients with FL needing frontline treatment will receive some form of immunochemotherapy (bendamustine-rituximab; rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone [CHOP]; obinutuzumab-CHOP). For patients relapsing after first-line immunochemotherapy, the best data belong to the lenalidomide-rituximab regimen, which is probably the second-line therapy of choice, although the data only apply to patients who are rituximab sensitive. For patients who are rituximab refractory, the PI3 kinase inhibitors have been an option but the safety profile for this class of agents has limited their usefulness. Tazemetostat seems to be an option preferable to PI3 kinase inhibitors, given the safety profile, and particularly if the patient has a mutated EZH2 gene. This test is available on several commercially available mutation panels and can be performed on archived formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue. However, establishing the mutational status is not mandatory. The FDA approval is broad – there is no requirement for the mutation and the waterfall plot (Figure 2) shows many unmutated patients can still derive benefit. Why this agent should work at all in the EZH2 wild-type patient is unclear, and more work should be done to clarify which wild-type patients are most likely to benefit. What I am saying here is we need another biomarker!

Competing Interests

Dr. Kahl indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.