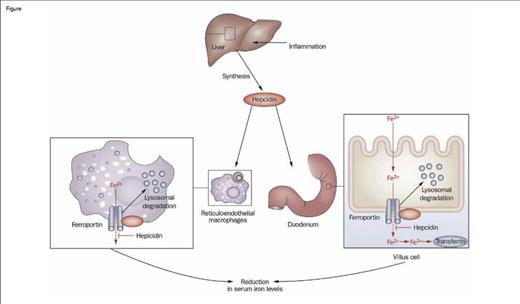

Hepcidin is a small peptide hormone produced by the liver that is the master regulator of iron homeostasis. Hepcidin mediates this function by impairing the export of iron from macrophages, duodenal enterocytes, and hepatocytes by binding to ferroportin, thereby driving internalization and degradation of this key transmembrane iron exporter (Figure). Consequently, hepcidin regulates both intestinal absorption of dietary iron and reutilization of iron derived from recycling of the hemoglobin of senescent red blood cells. A Diffusion article that I wrote last year ("Irons in the Fire: Developing New Therapies for Iron OverloadIrons in the Fire:Developing New Therapies for Iron Overload," The Hematologist, March/April 2013) focused on aberrant suppression of hepcidin expression, which leads to iron overload. The current article discusses the converse — enhanced expression of hepcidin that underlies the anemia of inflammation by limiting iron availability.

Hepcidin is an acute-phase reactant that is strongly induced by inflammation. Indeed, hepcidin was initially identified in a search for innate antimicrobial peptides. Chronic infections and other inflammatory diseases, including rheumatologic diseases and cancer, and chronic kidney disease, which results in decreased urinary clearance of hepcidin, are associated with abnormally high plasma concentrations of hepcidin. Consequently, the absorption and reutilization of iron is impaired, leading to the iron-restricted anemia of inflammation. This anemia is resistant to treatment with supplemental iron and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs). Therefore, effective treatment options are needed to aid in the management of symptomatic anemia of inflammation.

Role of Hepcidin in the Regulation of Intestinal Iron Absorption. Inflammation induces the synthesis of hepcidin by the liver, which then promotes the internalization and degradation of ferroportin, a transmembrane iron exporter, impairing the export of iron from macrophages and duodenal enterocytes. This process leads to decreased serum iron and, with time, an iron-restricted anemia. Thus, induced expression of hepcidin is a key mechanism of the anemia of inflammation.Figure adapted and redrawn from: Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anemia in patients with IBD. Jürgen Stein, Franz Hartmann & Axel U. Dignass. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 7, 599-610 (November 2010). doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2010.151

Role of Hepcidin in the Regulation of Intestinal Iron Absorption. Inflammation induces the synthesis of hepcidin by the liver, which then promotes the internalization and degradation of ferroportin, a transmembrane iron exporter, impairing the export of iron from macrophages and duodenal enterocytes. This process leads to decreased serum iron and, with time, an iron-restricted anemia. Thus, induced expression of hepcidin is a key mechanism of the anemia of inflammation.Figure adapted and redrawn from: Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anemia in patients with IBD. Jürgen Stein, Franz Hartmann & Axel U. Dignass. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 7, 599-610 (November 2010). doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2010.151

Cooke and colleagues, building on previous work with mouse monoclonal antibodies, developed a fully human, high affinity, hepcidin-neutralizing antibody (12B9m). This antibody was tested in a mouse model of anemia of inflammation where it was found to successfully treat ESA-refractory anemia. Antibody treatment increased plasma hemoglobin concentration in this model both by improving the hemoglobin content (“hemoglobinization”) of red blood cells and by stimulating production of reticulocytes. Antibody-mediated neutralization of hepcidin was shown to increase serum iron concentration in both mice and monkeys. There was no evidence that antibody treatment improved the anemia by modulating inflammatory status, as the production of cytokines and erythropoietin was unchanged following anti-hepcidin treatment. The antibody was found to be most effective when given simultaneously with an ESA compared with being given either two days before or two days after ESA treatment. Pharmacodynamic studies showed that weekly dosing was effective at modulating serum iron concentration and that a dose of 300 mg/kg achieved complete neutralization of hepcidin activity.

In Brief

Cooke and colleagues have developed an antibody that alleviates the anemia of inflammation in animal models by blocking hepcidin, thereby improving the availability of serum iron and increasing both the reticulocyte count and the hemoglobin content of red blood cells. A short-term practical offshoot of this research explored by the authors is the use of this antibody in a sandwich ELISA assay for the laboratory measurement of plasma hepcidin concentration. The ultimate goal of this research is to develop a pharmacologic reagent that can be used to modulate iron metabolism for the treatment of human disease, particularly the anemia of inflammation. This research provides cautious optimism for development of both a reliable and broadly available clinical test for quantifying hepcidin concentration (which would be a valuable aid in characterizing diagnostically challenging anemias) and a targeted therapy for anemia of inflammation, especially when the underlying cause of inflammation cannot readily be eliminated or controlled.

Competing Interests

Dr. Quinn indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.