When most hematologists happen to think about Factor XIII (FXIII), for example when taking a maintenance of certification (MOC) exam encouraged by The American Board of Internal Medicine, they might remember being called by an obstetric or pediatric colleague to assess a newborn with bleeding from the umbilical stump or by a neurologist or neurosurgeon to evaluate a patient with a spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage, the two most common clinical manifestations of congenital FXIII deficiency. Formerly known as fibrin-stabilizing factor, FXIII is a transglutaminase that circulates in the plasma as a proenzyme. When activated by thrombin, FXIII catalyzes the formation of intermolecular crosslinks between epsilon-N-(g-glutamyl)-lysine residues in the g- and a-chains of fibrin to stabilize and prevent dissolution of the clot, thereby promoting wound healing.

Vercellotti 1 11/12 2014

Red blood cells (RBCs) have long been thought to be bystanders in the process of clot formation, passively trapped in thrombi and doing little more than accounting for most of the bright color in the photographs of occlusive thrombi in the pulmonary arteries of patients whose cases were under discussion at our morbidity and mortality conferences. Recently, however, renewed attention has focused on the role of RBCs in thrombosis and hemostasis. RBCs can influence the clot’s fibrin network, its viscoelastic properties, and its rate of fibrinolytic degradation. Furthermore, RBCs can interact with fibrin(ogen), while red cell–derived microparticles can activate coagulation and complement pathways. A recent report showed that RBCs in the clot assume a polyhedral shape that functions to seal the clot and aid in clot retraction.1 Now, Dr. Maria Aleman and colleagues in the laboratory of Dr. Alisa Wolberg at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, demonstrate that FXIII is critical for RBC retention within clots, thereby directly affecting thrombus size and providing a potential new target for preventing or limiting the extent of venous thrombosis.

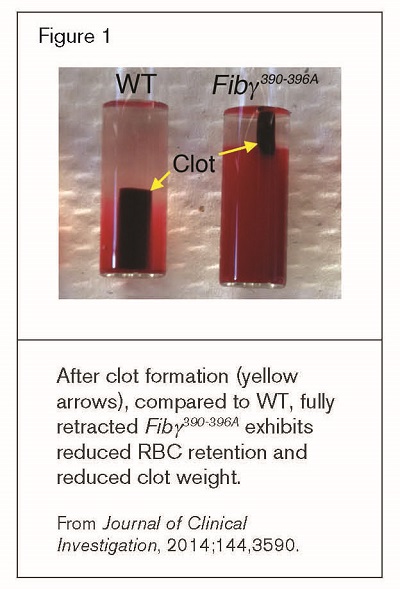

Two catalytic subunits of FXIII-A and two noncatalytic subunits of FXIII-B (the A and B components are the products of separate genes) form a noncovalent heterotetramer that circulates in a complex with fibrinogen in plasma. Amino acid residues 390-395 in the C-terminus of the g-chain of fibrinogen, upstream of the FXIIIa crosslinking sites, mediate interactions with both soluble proteins and cellular molecules including CD11b. Mice with a mutation of this region (Fibg390-396A) have normal fibrinogen levels, normal platelet aggregation, and normal fibrin polymerization, but clear bacteria poorly. The investigators examined thrombi in the Fibg390-396A mice and found smaller clots with reduced RBC content compared with thrombi in WT mice (Figure 1). RBCs from thrombi formed in the Fibg390-396A animals were extruded during clot retraction. Fibg390-396A did not bind to RBC nor did it bind Factor XIII. Plasma from Fibg390-396A mice had delayed FXIII activation and delayed fibrin crosslinking. In corollary studies, in vivo experiments in mice deficient in FXIII revealed smaller-than-normal thrombi with reduced RBC content. A 1970 report2 on a family with congenital FXIII deficiency showed excessive red cell fallout during clot retraction. This finding was not pursued, but here, Dr. Aleman et al. showed that FXIII-deficient human whole blood had reduced RBC retention following clot retraction, and the addition of purified FXIII to the deficient blood corrected this abnormality.

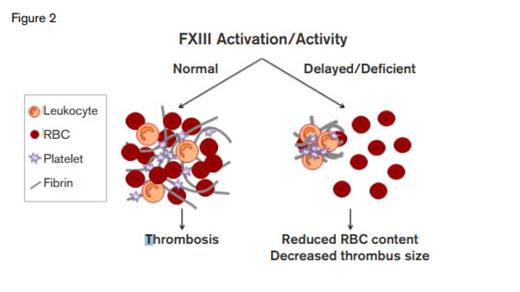

FXIII Activation/Activity. FXIII is a major determinant of thrombus size through its effects on red cell retention.Thanks to Maria Aleman and Alisa Wolberg, University of North Carolina for providing this figure.

FXIII Activation/Activity. FXIII is a major determinant of thrombus size through its effects on red cell retention.Thanks to Maria Aleman and Alisa Wolberg, University of North Carolina for providing this figure.

In Brief

This study critically redefines the physiology of venous thrombus formation and suggests a novel therapeutic target to reduce venous thrombosis. Rather than simply being snared in the fibrin net, RBCs are actively retained through a fibrin-FXIII–dependent process. On the one hand, this process would favor a seal to support wound healing. On the other hand, venous thrombus size is dependent on RBC content, and thus, hypothetically, clot size could be reduced by limiting RBC incorporation by interfering with FXIII function (Figure 2).

The number 13 is usually associated with bad luck, and fear of the number 13 is a specifically recognized Phobianeurosis, triskaidekaphobia. The studies of Dr. Aleman and colleagues, however, suggest that, in hematology, 13 is potentially a lucky number because development of specific inhibitors of FXIII is a strategy that could be exploited to lessen the morbidity and mortality of thromboembolic disease by reducing thrombus formation and size.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Vercellotti indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.