Although the Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care (TRICC) trial1 showed the benefits of a conservative transfusion strategy more than 15 years ago, many physicians remain skeptical about the safety of lower hemoglobin thresholds for red cell transfusion in critically ill patients. In particular, evidence from at least some clinical studies2,3 has suggested that higher hemoglobin targets may be advantageous for patients with septic shock.

To better define the benefits and risks of different hemoglobin thresholds for red blood cell (RBC) transfusion, Dr. Lars Holst and colleagues conducted a multicenter, parallel-group trial that randomized intensive care unit (ICU) patients with septic shock to receive one unit of leukoreduced red cells either at a hemoglobin concentration of 9 g/dL or less (higher threshold) or at a hemoglobin concentration of 7 g/dL or less (lower threshold). The primary outcome measure was death at 90 days.

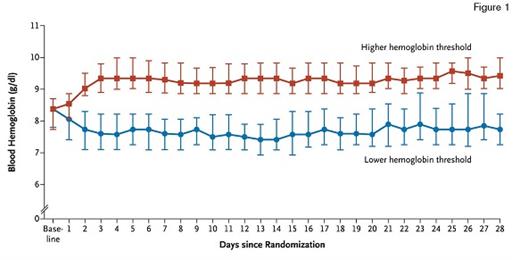

Median Daily Lowest Levels of Blood Hemoglobin in the Lower-Threshold Group and the Higher-Threshold Group. The I bars indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles. From The New England Journal of Medicine, Lars B. Holst et al, Lower versus Higher Hemoglobin Threshold for Transfusion in Septic Shock, 371, 1381-91. Copyright © 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

Median Daily Lowest Levels of Blood Hemoglobin in the Lower-Threshold Group and the Higher-Threshold Group. The I bars indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles. From The New England Journal of Medicine, Lars B. Holst et al, Lower versus Higher Hemoglobin Threshold for Transfusion in Septic Shock, 371, 1381-91. Copyright © 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

The Transfusion Requirements in Septic Shock (TRISS) trial was conducted at 32 sites in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland between December 2011 and December 2013. Randomization was stratified by study site and by the presence or absence of active hematologic cancer. More than 85 percent of screened patients were randomized; the most common reason for exclusion was prior transfusion of RBCs. Of 1,005 patients who underwent randomization, 998 (99.3%) were included in the primary outcome (mortality) analysis. The baseline clinical characteristics of the two groups were similar, including age (median age, 67 years for both groups) and severity of illness scores. Although approximately 14 percent of patients in each group had chronic cardiovascular disease, patients with acute myocardial infarction were excluded. The median number of RBC units received was less in the lower threshold group (one unit vs. four units).

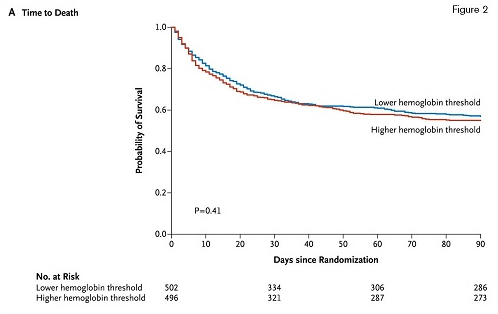

The Survival Curves, With Data Censored at 90 Days, in the Two Intervention Groups in the Intention-to-Treat Population. From The New England Journal of Medicine, Lars B. Holst et al, Lower versus Higher Hemoglobin Threshold for Transfusion in Septic Shock, 371, 1381-91. Copyright © 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Masschusetts Medical Society.

The Survival Curves, With Data Censored at 90 Days, in the Two Intervention Groups in the Intention-to-Treat Population. From The New England Journal of Medicine, Lars B. Holst et al, Lower versus Higher Hemoglobin Threshold for Transfusion in Septic Shock, 371, 1381-91. Copyright © 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Masschusetts Medical Society.

Ninety days after study entry, overall mortality was 43 percent in the lower-threshold group, and 45 percent in the higher-threshold group (relative risk, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.78 to 1.09; p=0.44). Neither adjustment for baseline risk factors nor per-protocol analyses altered the findings. Secondary outcome measures included the use of life support at days 5, 14, and 28 after randomization; serious adverse reactions (including transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload) while in the ICU; and cerebral, myocardial, limb, or intestinal ischemic events while in the ICU. No statistically significant difference between treatment groups was observed for any of these secondary endpoints.

In Brief

The TRISS investigators and study sites deserve credit for a very well designed and highly successful study of persons with septic shock (but no evidence of acute myocardial infarction). Recruiting patients with critical illness is difficult, and the high enrollment rate among eligible individuals is impressive. In addition to highlighting the very grave prognosis associated with septic shock, the TRISS trial has identified yet another patient population in which lower hemoglobin concentrations should be tolerated. Patients randomized to higher hemoglobin thresholds fared no worse than the patients in the intervention group, but they were exposed to more than twice the number of RBC units and did not experience a risk reduction for any of the reported outcomes (primary or secondary). Considering the previous high-quality evidence4 favoring more conservative transfusion thresholds, the TRISS trial shows that clinicians should think carefully before recommending hemoglobin thresholds higher than 7 g/dL in patients with septic shock.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Garcia indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.