Einstein had it right when it comes to theoretical physics, but wrong when it comes to medicine. Sir William Osler was more on target when he said, “The science of medicine is uncertainty. The art of medicine is probability.”

Most of our knowledge of a relationship between exposure to cancer therapy and developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) comes from epidemiological studies. So it is important to remember epidemiology deals with associations, not cause and effect. Also, we need to avoid the logical fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc (after this, therefore because of this). Specifically, just because AML or MDS follows prior cancer therapy does not mean these diseases were caused by the therapy (see Note 1).

It is also important to recall epidemiological studies typically consider the association between an exposure and an outcome in a cohort, not a person. Even exposures strongly associated with an increased risk of AML or MDS in a cohort do not allow us to impute this exposure as causative in a specific person with AML or MDS. Here we need to rely on a different calculation: probability of causation in an individual; namely, the likelihood his/her exposure caused or contributed to his/her developing AML or MDS. This is complicated. For example, what if the exposure did not cause AML or MDS because the person would have developed it in the absence of exposure? What if the exposure merely accelerated developing AML or MDS or made it worse? More on this later.

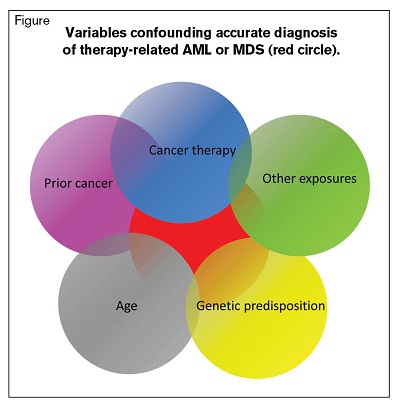

Variables Confounding Accurate Diagnosis of Therapy-Related AML or MDS (Red Circle)

Variables Confounding Accurate Diagnosis of Therapy-Related AML or MDS (Red Circle)

To accurately estimate whether a person’s AML or MDS is caused by or contributed to by a prior exposure, we need to know many variables. For example, there is a strong association between age and background incidences of AML and MDS in unexposed persons. Two people, one 20 and the other 70 years old, who develop AML or MDS 10 years after an exposure, have entirely different probabilities of causation. Also, data from survivors of atomic bomb explosions show age at time of exposure and gender are associated with risk of developing AML and MDS.1 We also need to consider the interval between exposure and developing AML or MDS. Several of these variables are confounded (Figure). For example, when we studied the interval to develop AML or MDS after radiation therapy of a first cancer (with or without chemotherapy), we found different latencies for males and females.2 Also, AML and MDS have different latencies under different exposure conditions. Latency for AML after radiation therapy can be very brief — less than two years — whereas it is generally believed to have been 10 to 15 years in atomic bomb survivors and to have lasted up to 30 years postexposure. However, the minimal latency estimate is questionable, as there was no comprehensive follow-up of the survivors until roughly 1955. MDS seemed to begin much later, starting at about 30 years postexposure and continuing 60 years later, but there are no early data.3 These are only some of the variables requiring consideration. We also need to evaluate individual exposure to other known leukemia-causing agents such as benzene and cigarette smoking. One bottom-line conclusion: If a person who now has AML or MDS were exposed only to radiation therapy (not drugs) for a prior cancer, and the exposure was more than two to three years before, it is quite unlikely their AML or MDS would be caused by their prior radiation therapy exposure.

If a hematologist considers all these data, it is sometimes possible to give a best estimate value of the likelihood an exposure caused or contributed to a person developing AML or MDS. However, such best estimate values are uncertain and should be accompanied by a confidence or credibility interval indicating a range of possible values. In reality, it is often impossible from epidemiological data to distinguish between cases of AML or MDS where the exposure caused or contributed to developing the disease (etiologic cases) and cases in which the person would have developed AML or MDS anyway (see Note 2).

The process for determining probability of causation differs substantially from what hematologists do when they encounter a person with AML or MDS exposed to potential leukemia-causing drugs and/or ionizing radiation. All too often, the reaction is: “If you had cancer and were treated, and you now have AML or MDS, you must have therapy-related AML or MDS.” This is not to say hematologists do not consider other data such as whether there are cytogenetic abnormalities (such as del[5/5q] or del[7/7q]) associated with therapy-related AML or MDS. However, it is important to recall the frequency of these cytogenetic abnormalities increases with increasing age in persons with AML or MDS, unrelated to therapy.4 And because cancer incidence increases with age, persons with suspected therapy-related AML or MDS are likely to be old. The same caveat applies to mutations thought to be associated with therapy-related AML or MDS, such as TP53. Consider recent data indicating a high frequency of TP53 mutations and even clonal hematopoiesis in older persons with no hematologic disorder.5,6 As discussed, details of prior exposures are rarely known. How often have you heard a colleague say a person with newly diagnosed AML or MDS had chemotherapy or radiation therapy for a prior cancer without knowing any details?

Statisticians and epidemiologists would likely judge our method of assigning causation in most cases of therapy-related AML or MDS to be without scientific merit. This is because the relationship between an exposure and risk of developing therapy-related AML or MDS is uncertain in most instances. Some cases of AML and MDS are therapy-related, especially in persons with a genetic predisposition.7 However, we typically have insufficient data to designate a specific person as having therapy-related AML or MDS. One limitation is that for most drug exposures, there are no specific risk estimators. The consequence is that risk estimates from exposures to the anticancer drugs are qualitative rather than quantitative. Phrases such as “reasonably expected to be associated,” “likely to be associated,” or “possibly associated” are used rather than numerical risk estimators. This poses a huge obstacle to precise risk estimation. Given these considerations, it is surprising the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of AML includes the category “acute myeloid leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes, therapy related (t-AML and t-MDS).”8 Even more amazing, the WHO classification goes on to specify two types: alkylating agent/radiation therapy related and topoisomerase II inhibitor related and gives a 10- to 15-point detailed description of each. How this is possible is a mystery to us. How is anyone supposed to know with reasonable certainty who has therapy-related AML or MDS?

Prior radiation exposure differs from drug exposure in that quantitative risk estimators are available.9,10 However, calculating probability of causation requires knowing several exposure- and subject-related variables. Consequently, although attributable risk from radiation exposures can be more precisely estimated than risk after drug exposures, the data needed for this calculation are seldom available to the hematologist.

Given these considerations, it is unlikely or impossible that a hematologist can accurately estimate whether a case of AML or MDS in a person who received prior cancer therapy is therapy-related. How important is precise estimation? Probably not very important, but it is important to have a qualitative estimate such as “likely,” “unlikely,” or “uncertain.” Boundaries to these estimates might be less than 30 percent, 30 to 70 percent, or more than 70 percent. This process can be considered somewhat analogous to the more precise expression of uncertainty incorporated in a confidence or credibility interval.

Many things flow from a reasonably accurate estimate of whether a person’s AML or MDS is therapy-related. For example, deciding whether to give induction chemotherapy, hypomethylating drugs, or low-dose cytarabine may be influenced by this estimate. Another example is whether to consider a hematopoietic cell transplant. For each of these therapies and others, an imprecise or incorrect estimate of whether AML or MDS is therapy related can result in under- or over-treatment.

Where does this leave us? We suggest hematologists be more cautious in saying a person has therapy-related AML or MDS. They need to try to ascertain precise details of prior exposures and consider possible confounders, especially the normal steep age-related increases in AML and MDS. They also need to consider older persons with AML are more likely to have had a prior cancer, whether or not their AML or MDS is therapy related, and that many persons with cancer, treated or not, are at increased risk of developing AML or MDS. Part of this may be a surveillance bias, and part may result from biological, genetic, or environmental factors. If there are insufficient data to make a reasonable best estimate value and indicate a confidence interval in a case of AML, one should avoid using the designation therapy related AML. However, with sufficient data, the hematologist should consider qualifying his/her estimate with terms which convey the level of certainty such as “likely,” “unlikely,” or “uncertain.” Adopting these suggestions can help prevent inaccurate attributions of causation and decrease the likelihood of inappropriate therapy decisions. As Francis Bacon said, “Without certainty, science is nothing more than seemingly sophisticated guesswork.” How we get to certainty is another issue entirely.11 To quote Pascal Blaise: “It is uncertain everything is uncertain.”

Note 1: Therapy-related AML or MDS also refers to persons developing these disorders after therapy for others diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Sometimes it refers to persons exposed to diagnostic radiological procedures such as computed tomography or positron emission tomography scans or radionuclides for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes and/or to persons receiving intense immune suppression. We consider these concepts similar.

Note 2: Cases are associated with the baseline risk for persons of like age and gender and, ideally, with the same disease history but not exposed to potentially leukemogenic drugs and/or ionizing radiations.

Acknowledgment: Dr. Gale acknowledges support from the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme.

References

Author notes

“Imagination is more important than knowledge.” –Albert Einstein

Competing Interests

Dr. Gale, Dr. Bennett, and Dr. Hoffman indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.