The Mayo Clinic is one of the largest academic medical centers in the world, with more than 2,500 physicians and scientists contributing their expertise to almost every conceivable medical condition known to science. Within this medical enterprise, the Multiple Myeloma Program has managed to bring together more than 30 clinicians and researchers to focus on one rare cancer, representing just 1 percent of all malignancies. How does one maintain academic output, growth, collegiality, and trust while playing in a small sandbox? In other words, is there a recipe for the success of our program, and can it offer models that can be replicated elsewhere?

The story of the program for multiple myeloma and related disorders at the Mayo Clinic is both fascinating and instructive, and it can be traced back more than 50 years ago when one of us, Dr. Bob Kyle, joined the institution as a fellow. In 1959, Dr. Kyle stared at a serum protein electrophoretic pattern for the first time. Little did he realize at that time what he was getting himself into. Soon, one pattern became 100, and 100 became 1,000, and 1,000 became countless. Within one year, a review of the more than 6,500 serum protein electrophoretic patterns performed at the Mayo Clinic led to a 1960 publication in JAMA, before the concept of monoclonal/polyclonal gammopathies was introduced. In that paper, Dr. Kyle described that a height/width ratio greater than 4:1 was associated with plasma cell disorders (multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, or amyloidosis), while those with a lower ratio had polyclonal processes (chronic, active hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, or other inflammatory diseases).

After joining the Mayo Clinic staff in 1961, Dr. Kyle realized that to pursue the study of plasma cell disorders, he needed a laboratory and better techniques. He spent a week at the National Cancer Institute with Drs. John Fahey and William Terry learning the technique of immunoelectrophoresis − a more sensitive and specific test that was needed to confirm and type abnormal monoclonal proteins detected on standard electrophoresis. Against all odds and obstacles, Dr. Kyle obtained permission from the leaders of the Mayo Clinic to spend two hours each day in the laboratory performing immunoelectrophoresis. Although it meant adding extra patients to his already busy clinical practice, Dr. Kyle realized that to understand the new laboratory findings, he had to see and follow all patients he identified with abnormal monoclonal proteins. The number of tests performed in the laboratory increased rapidly, and the practice grew accordingly.

Perhaps the most seminal event was Dr. Kyle’s foresight to establish a serum bank in the early 1960s to save any remaining samples. A close second was the establishment of a database at around the same time, which contained clinical and laboratory data from all patients with a monoclonal plasma cell disorder. The database consisted of IBM punch cards with a maximum limit of 80 entries per patient. The third key element was the establishment of the program as a separate unit within the Division of Hematology, dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma and related plasma cell disorders.

Dr. Kyle was the program for years. Several discoveries (many of which have become among the most cited articles in the field) and almost 15 years later, this one-man myeloma program added a second staff consultant in 1975, Dr. Philip Greipp. This was followed in 1982 by the addition of Dr. Morie Gertz. These three pillars of the program attracted residents and fellows like magnets. Fellows understood that the myeloma program was vibrant and that it offered exceptional opportunities for research and career development. Key recruits in the ensuing years were Drs. Thomas Witzig, John Lust, Martha Lacy, Angela Dispenzieri, Rafael Fonseca, and the other author, Dr. Vincent Rajkumar. Soon the program expanded to the Scottsdale, Arizona, location under the leadership of Dr. Fonseca, who promptly had the audacity to recruit two of his closest competitors in the field of myeloma genetics, Dr. Leif Bergsagel and Dr. A. Keith Stewart. Yes, they came to be known as the three musketeers.

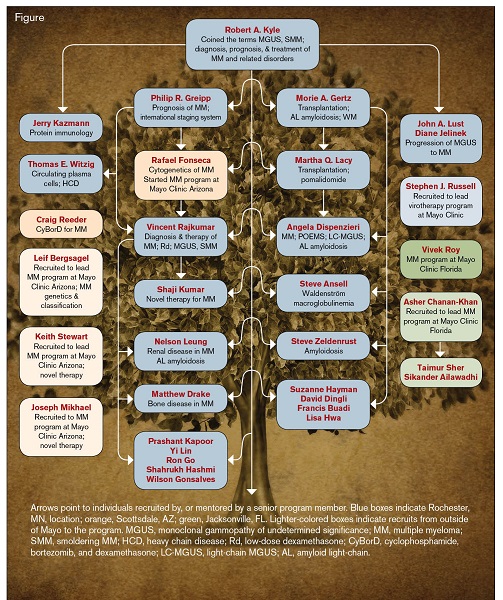

Arrows point to individuals recruited by, or mentored by a senior program member. Blue boxes indicate Rochester, MN, location; orange, Scottsdale, AZ; green, Jacksonville, FL. Lighter-colored boxes indicate recruits from outside of Mayo to the program. MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM, multiple myeloma; SMM, smoldering MM; HCD, heavy chain disease; Rd, low-dose dexamethasone; CyBorD, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; LC-MGUS, light-chain MGUS; AL, amyloid light-chain.

Arrows point to individuals recruited by, or mentored by a senior program member. Blue boxes indicate Rochester, MN, location; orange, Scottsdale, AZ; green, Jacksonville, FL. Lighter-colored boxes indicate recruits from outside of Mayo to the program. MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM, multiple myeloma; SMM, smoldering MM; HCD, heavy chain disease; Rd, low-dose dexamethasone; CyBorD, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; LC-MGUS, light-chain MGUS; AL, amyloid light-chain.

Today, 40 years later, the growth and transformation of the Mayo Clinic Multiple Myeloma Program is astonishing. The serum bank has more than 250,000 samples; the database now contains almost 50,000 patients. The IBM punch cards are long gone, replaced by the most modern of statistical systems, which can be interrogated to answer simple and complex questions. Today, there are more than 25 clinical faculty members (more than 10 at the professor level) with a career focused on myeloma and related disorders, across all three geographical sites of the Mayo Clinic (Minnesota, Arizona, and Florida; Figure). All are engaged in research, education, and practice, with each member providing a vital and different emphasis. Although the contributions of each member to the field individually and collectively are extensive, it is worth examining how, even in a small field, it is possible to divide the problem into many parts, where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Dr. Kyle defined and characterized monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM), and several other entities. Dr. Greipp developed the International Staging System. Dr. Gertz focused his attention on amyloidosis, while Dr. Dispenzieri described light-chain MGUS and has led research on POEMS syndrome. Dr. Bergsagel developed the first molecular cytogenetic classification of myeloma, and Dr. Fonseca identified the association between cytogenetic classification and prognosis. Dr. Lust studied mechanisms of progression. Dr. Witzig was one of the first to describe the identification and prognostic value of circulating plasma cells. Dr. Stewart identified biomarkers of resistance to immunomodulatory drugs and led the development of carfilzomib. Dr. Rajkumar led early trials of thalidomide and lenalidomide, while Dr. Lacy led most of the initial studies of pomalidomide.

With so many individuals performing at a high level, we were able to attract the very best in the ensuing years. Dr. Asher Chanan-Khan built the Jacksonville myeloma program. Dr. Shaji Kumar has become one of the finest clinical trialists in myeloma. Dr. Stephen Ansell has taken on the challenge of Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Dr. Stephen Russell has developed virotherapy from bench to manufacturing to bedside, culminating in the measles virus trials for relapsed/refractory myeloma. Dr. Craig Reeder developed the CyBorD regimen, one of the most commonly used treatments in myeloma. Dr. Joseph Mikhael has become a leader in education. The genealogy of the Mayo Myeloma program (Figure) has deep roots with many branches, including many alumni who have gone elsewhere to play a major role in the field; notably, Dr. Brian Durie, founder of the International Myeloma Foundation, who developed the Durie-Salmon Staging system in 1976.

What do we think are the main factors responsible for the remarkable success of the program? The first is the setting. It is indeed easier to succeed when there is a patient-centered organization such as the Mayo Clinic behind you. The breadth of expertise in the institution also helps the program work at a high level with other related fields, especially imaging, nephrology, endocrinology, and cardiology. Second are the unique program resources, specifically the biobanks and the database, started decades ago. They enables us to address questions that would take years to answer if we had to start now. Third is the people. Clearly we have been fortunate to attract and retain (our retention rate is almost 100%) the best and brightest in the field. It took a lot of effort to build the program, and a lot more work is needed to maintain its standards and integrity. Fourth is the ability to forge consensus. Despite philosophical differences, we have been able to synthesize the best available data and come up with a consensus approach to clinical practice ( www.msmart.orgwww.msmart.org), which is essential not only for teamwork and excellence in patient care, but also for generating the next research questions. Fifth, NIH funding in the form of program grants are vital in supporting core resources that are usually hard to fund via other means. Recent cutbacks, therefore, are a concern. Finally, perhaps the most critical element of our success is independence. Each investigator in the program has the freedom to be a leader in the field. There is no hierarchy, and members of the myeloma group are encouraged to pursue their own interests and not become cogs that help one or two senior people to succeed. People speak their minds openly without fear of retribution. We know we can offer more to the field by working together. Additionally, there is an unbelievable amount of trust; and for any program, trust, ultimately, is everything.

Author notes

Editor’s Note: I’m not a foodie, but I am a fan of chef Anthony Bourdain’s "Parts Unknown," a weekly globe-trotting series that transports viewers to local cultures and culinary delights. I was particularly drawn to an episode from Lyon, France since most of my father’s side of the family has resided in that city for more than 75 years. Lyon is famous for having been the epicenter of “the System,” which employed a high-pressured, militaristic system of grooming Master Chefs. “The System” was borne of a fascinating genealogy of female cooks, Les Mères, and most famously La Mère Brazier (the first chef to attain six Michelin stars for two restaurants), who dominated the culinary scene between and during the World Wars to fill vacancies left by men serving in the military. La Mère Brazier was the mentor of Chef Paul Bocuse, a living legend and ambassador of French nouvelle cuisine. Importantly, Bocuse and his contemporaries trained and inspired successive generations of chefs and restaurateurs who have dispersed beyond France’s borders to share their disciplined techniques and ground-breaking dishes with an international clientele.

Competing Interests

Dr. Rajkumar and Dr. Kyle have no relevant conflicts of interest.