Unprovoked deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism may be an early sign of undiagnosed cancer, with up to 10 percent of patients receiving a diagnosis of cancer in the year following a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism.1 Individuals with venous thromboembolism are two to four times more likely to be diagnosed with cancer when compared with the general population. A recent study, which examined patients with first-time splanchnic venous thrombosis in 1,191 Danish patients, found that such patients were 33 times more likely to be diagnosed with cancer in the three months following this diagnosis. Liver cancer, pancreatic cancer, and myeloproliferative neoplasms were the most common tumors diagnosed.2 Given such statistics, screening for occult tumors in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism is thought to allow for early detection and intervention. The question is, how aggressive should such screening be?

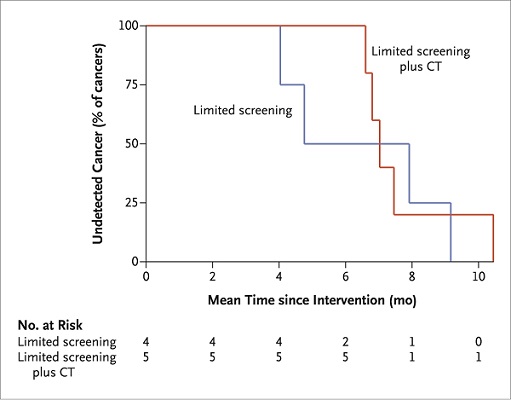

Kaplan-Meier Curves for Time to Detection of Missed Occult Cancer. From New England Journal of Medicine, Carrier M et al, Screening for Occult Cancer in Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism, 10.1056/NEJMoa1506623. Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

Kaplan-Meier Curves for Time to Detection of Missed Occult Cancer. From New England Journal of Medicine, Carrier M et al, Screening for Occult Cancer in Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism, 10.1056/NEJMoa1506623. Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

Dr. Marc Carrier and investigators for the Screening for Occult Malignancy in Patients with Idiopathic Venous Thromboembolism (SOME) study conducted a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial in Canada. 854 patients were randomized to undergo either limited screening or limited screening in combination with comprehensive computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis, which included a virtual colonoscopy and gastroscopy, biphasic enhanced CT of the liver, parenchymal pancreatography, and uniphasic enhanced CT of the distended bladder. Limited screening for occult cancer included basic blood testing, chest radiography, and screening for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer. The primary outcome measure was biopsy-proven cancer missed by the screening strategy and detected by the end of a one-year follow-up period. Results showed that 33 (3.9%) of total patients had a new diagnosis of occult cancer, with 14 (3.2%) of 431 patients diagnosed in the limited-screening group and 19 of 423 (4.5%) in the CT plus limited screening group. There was no statistical difference between these two groups (p=0.28). The primary outcome analysis showed four occult cancers missed in the limited screening strategy and five missed by the CT plus limited screening group. No significant difference between the two groups was detected in cancer-related mortality or in mean time to a cancer diagnosis.

In Brief

These results are consistent with a previous prospective, nonrandomized cohort study that compared a limited screening strategy for occult cancer with a strategy that included mammography for women and CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis in all patients.3 This study did not show any significant difference in the diagnosis of occult cancers or in overall mortality, with a follow-up of 2.5 years. An earlier randomized controlled trial involved patients with a negative limited screening result for occult cancer, in which subjects were randomized either to additional testing with ultrasonography, CT of the abdomen and pelvis, endoscopy, and tumor marker measurements, or to no further testing.4 This trial was discontinued early due to recruitment difficulties but showed an increased detection of early-stage cancer in the extensive-screening strategy group (nine of 14 [64%]) versus the limited-screening group (two of 10 [20%]; p=0.047). However, there was no significant difference in cancer-related deaths between the two groups during a two-year follow-up period. In conclusion, in this current study, SOME Investigators found a low prevalence of occult cancer in patients with a first unprovoked deep-vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism. Furthermore, routine screening for occult cancer with CT of the abdomen and pelvis did not provide a clinically significant benefit over routine screening alone.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves for time to detection of missed occult cancer. From New England Journal of Medicine, Carrier M et al, Screening for Occult Cancer in Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism, 10.1056/NEJMoa1506623. Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. George indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.