Mast cells are perhaps not the most comfortable topic of discussion for hematologists. In fact, if we were asked to talk for one full minute on the topic of a mast cell, I’m not sure how many of us could continue beyond 40 seconds. I wonder how one of hematology’s founding fathers, Paul Ehrlich, who wrote his own PhD thesis on mast cells, would feel about the apparent lack of knowledge regarding this topic. Indeed, he gave the cell its name — Mastzelle, from the Greek term for breast — a choice that was taken to represent his view of the nourishing nature of these cells within connective tissue. Yet this cell is surely one of our own — derived from a hematopoietic precursor which expresses CD34, CD13, and the KIT tyrosine kinase — and is characterized by the expression of histamine and heparin. The physiological role of the mast cell is still being explored, but encompasses myriad functions related to allergy, trophic support of developing tissue, and innate immunity.

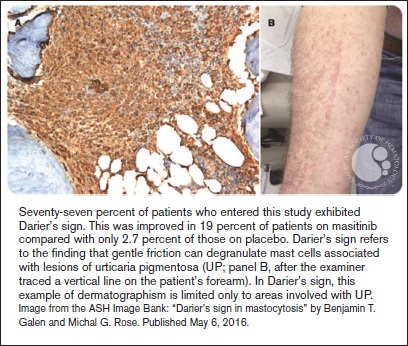

"Seventy-seven percent of patients who entered this study exhibited Darier’s sign. This was improved in 19 percent of patients on masitinib

"Seventy-seven percent of patients who entered this study exhibited Darier’s sign. This was improved in 19 percent of patients on masitinib

Clonal proliferations of mast cells are not common, but their clinical consequences can be dramatic and severe. Systemic mastocytosis (SM) refers to the accumulation of mast cells in the bone marrow or other internal organs. The major diagnostic criterion for the disease is the presence of aggregates of at least 15 mast cells in bone marrow or another extracutaneous organ. Four diagnostic minor criteria include: more than 25 percent atypical (spindled) mast cells in the mast cell aggregates; aberrant mast cell immunophenotype with expression of CD25 and/or CD2; D816V or another activating point mutation in the KIT gene, and an increased serum tryptase level. One major and one minor, or three minor criteria, are sufficient to make a diagnosis of SM. The KIT D816V mutation is found in 90 percent of patients and drives excessive proliferation of the tumor cells. Inhibitors with activity against wild-type KIT and the KIT D816V mutant protein are either under review by the health regulatory agencies (e.g., midostaurin) or in early-phase clinical trials (e.g., BLU-285) as treatment for patients with advanced SM.

This clinical study reports on the outcome of a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial using masitinib in the treatment of patients with severely symptomatic forms of systemic mastocytosis. At the outset it should be noted that these patients had indolent SM (include the subvariant smoldering SM), and did not include the poor prognostic group of advanced SM with organ dysfunction. As such, these patients can generally expect a normal life expectancy, though around one third of patients within this category experience severe symptoms due to mast cell mediator release and represent the type of patients that might benefit from this therapy. Masitinib is an inhibitor of the wild-type KIT protein, but not the common D816V variant. Importantly, it also inhibits the LYN and FYN proteins, which are mediators of mast cell survival and mediator release.

During the accrual period from 2009-2015, the authors studied 135 patients (although only 108 formally satisfied the WHO criteria for systemic mastocytosis) and were randomized to oral masitinib (6 mg/kg daily in two daily doses) or placebo, with allowance that optimal symptomatic medications could be continued. All the patients reported severe symptoms within the four categories of pruritis, flushing, depression or fatigue; it is noteworthy that the latter two criteria are relatively unappreciated in this disorder. These problems relate to mast cell mediator release and it was no surprise that first-line therapies for the patients had included agents to control mediator symptoms such as antihistamines, proton pump inhibitors, sodium cromoglicate, antidepressants, and leukotriene antagonists.

The primary end-point of the study was somewhat unusual and was based on a 75 percent or more improvement in any one of the aforementioned four major symptom groups within the first 24 weeks of treatment. Importantly, 18.7 percent of patients who were taking masitinib achieved this endpoint compared to 7.4 percent of patients in the placebo group. Of interest, at week 24, there was a 20.2 percent absolute mean change in the serum tryptase level from baseline between the two groups in an intent-to-treat analysis: a decrease of 18.0 percent in the masitinib arm versus an increase of 2.2 percent in the placebo arm (p<0.0001). Also, urticaria pigmentosa lesions on masitinib therapy decreased by an average body surface area of 12.3 percent versus an increase of 15.9 percent for the placebo group — an absolute difference of 28.2 percent (p= 0.021). Masitinib-associated clinical benefits were generally sustained during a two-year extension period. Treatment was generally well tolerated, though an excess incidence of diarrhea, rash, and asthenia were seen in 9 percent 6 percent, and 4 percent of patients, respectively, in the masinitib group. For these patients with lower-risk disease who have a normal life expectancy, these side effects need to be weighed against the potential benefits of the drug in mitigating SM-related symptoms.

In Brief

This is the first phase III randomized study in SM, and focuses attention on the unmet need of patients with indolent forms of SM who have refractory mediator symptoms despite the use of conventional medications. The biologic basis for masitinib’s impact on mast cell activation symptoms remains ambiguous since the drug does not inhibit the canonical KIT D816V protein found in most patients. It is postulated that depletion of wild-type mast cells or inhibition of KIT-independent mechanisms of mast cell activation (e.g., via signalling through LYN and FYN) may be relevant in such patients, but biomarker studies are needed to validate this hypothesis.

Competing Interests

Dr. Moss indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.