Patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) — deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and/or pulmonary embolism (PE) — have a 30 percent risk of recurrent VTE over five years if anticoagulation is stopped after the initial three to 12 months of acute VTE treatment.1 While men have a higher risk of recurrence than women (over 5 years, 36% vs. 24%, respectively), the risk in both is considered to be high enough that evidence-based guidelines recommend long-term anticoagulation for patients with unprovoked VTE, independent of sex, if they tolerate anticoagulation well and are not at high risk for bleeding.2,3

In 2008, Dr. Marc A. Rodger and colleagues published the “HERDOO2 rule,” created from the results of a prospective multicenter cohort study of 646 participants with a first, unprovoked VTE treated with short-term anticoagulation.4 No predictors for a low risk of recurrence were found in men, but in women, a low-risk group was identified (Table). They concluded that women with unprovoked VTE with a HERDOO2 score of 0 to 1 could discontinue anticoagulation, while women with a score of at least 2, and all men, should continue.

The work of Dr. Rodger et al is a validation study of this HERDOO2 rule. 2,785 subjects (44.3% female) with first unprovoked VTE (proximal DVT or PE) who had completed five to 12 months of anticoagulation were enrolled at 44 medical centers in seven countries. Index VTE events associated with minor or weak risk factors, such as travel, exogenous estrogens, minor immobilization or minor surgery were considered unprovoked and eligible for enrollment; patients with strong thrombophilias were excluded. Women with a HERDOO2 score of at least two and all men were advised to continue long-term anticoagulation; women with a score of zero to one were advised to discontinue anticoagulants. Patients were followed for one year and assessed for the primary outcome, recurrent major VTE (proximal DVT and segmental or greater PE). Not all patients followed the recommendation to discontinue or continue anticoagulation based on the decision rule’s risk assessment, allowing a risk of recurrence assessment in the various groups listed below.

In low-risk women who discontinued anticoagulation (n = 591), VTE recurrence per patient-year was 3.0 percent (95% CI, 1.8-4.8%). In high-risk women and men who discontinued anticoagulation (n = 323), it was 8.1 percent (95% CI, 5.2-11.9%). In high-risk women and men who continued anticoagulation (n = 1,802), it was 1.6 percent (95% CI, 1.1-2.3%), I and in high-risk women who discontinued anticoagulation (n = 101), VTE recurrence per patient-year was 7.4 percent (95% CI, 3.0-15.2%).

This study validated the original HERDOO2 rule: Women with a first unprovoked VTE event and a HERDOO2 score of 0 to 1 have a low risk of recurrent VTE and can safely discontinue anticoagulants, whereas women with a score of at least 2, and all men, have a high risk of recurrence and should continue long-term anticoagulation. Noteworthy is that 51.3 percent of women with unprovoked VTE were classified as low risk, appropriate for discontinuation of anticoagulation. Thus, long-term anticoagulation, as recommended by existing guidelines, could be avoided in a substantial number of women if following HERDOO2.

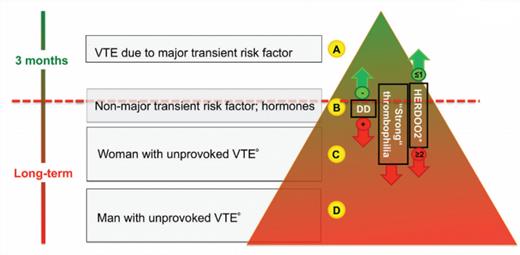

Recurrence Triangle for Venous Thromboembolism (VTE). Patient A: major transient risk factor associated VTE; patient B: minor/weak risk factor associated VTE, such as travel, estrogens, minor immobility, minor surgery; patient C: woman with true unprovoked VTE; patient D: man with unprovoked VTE. Abbreviations: DD, D-dimer; VTE, venous thromboembolism.VTE is a proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.HERDOO2 score is only to be used in women.

Recurrence Triangle for Venous Thromboembolism (VTE). Patient A: major transient risk factor associated VTE; patient B: minor/weak risk factor associated VTE, such as travel, estrogens, minor immobility, minor surgery; patient C: woman with true unprovoked VTE; patient D: man with unprovoked VTE. Abbreviations: DD, D-dimer; VTE, venous thromboembolism.VTE is a proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.HERDOO2 score is only to be used in women.

We do not routinely use the HERDOO2 score for decision-making on length of anticoagulation in women with a history of unprovoked VTE, for five reasons. 1) There is equivocal evidence in the literature that the predictors identified in the HERDOO2 cohort are universal predictors of recurrence in women. Discrepant data exist on whether obesity is truly a risk factor for recurrence; while some studies have, similar to Dr. Rodger et al, found that obesity is a risk factor for recurrence,5-7 others have not confirmed this.8 Discrepant data also exist on whether older age is a risk factor for recurrence; while some studies have found older age to be a recurrence risk factor,8 others have not confirmed this9,10 and even found the opposite (e.g., younger age < 50 years increases risk of recurrence).11 2) The unprovoked VTE group was a mixture of true unprovoked VTE and VTE associated with minor or weak transient risk factors and was treated and analyzed as one homogenous group. However, previous data suggest that risk of recurrence in the unprovoked versus minor risk factor–associated groups is different.12 3) Patients with strong thrombophilias were excluded from the present study. It is not clear how inclusion of such patients would have influenced the results. Given that strong thrombophilias are not very prevalent, inclusion would likely not have changed the results. Nevertheless, applying this score to a more general, untested population and using it for clinical decision making has some imponderability factor. 4) Only 25.4 percent of study patients were on a non-warfarin anticoagulant at baseline, but many with VTE are now being treated with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC). It is not clear whether the HERDOO2 score would also be valid if applied to patients on DOACs, as it is not known whether a D-dimer obtained while on a DOAC predicts recurrent VTE in a similar manner as it does while on warfarin. 5) In this study, the HERDOO2 score was applied after five to 12 months of initial anticoagulation, but it is unclear if the score remains valid if applied earlier after initial VTE (i.e., after 3 months of anticoagulation, a time when many physicians are making the decision to continue or discontinue anticoagulation). Edema often decreases after the initial DVT, but postthrombotic pigmentation increases, and these changes may influence the HERDOO2 score if obtained at an earlier time.

Table. HERDOO2 Scoring

| . | Predictor . | Scoring . |

|---|---|---|

| H | Hyperpigmentation | 1 point total, if any one of these criteria is present |

| E | Edema | |

| R | Redness of either leg | |

| D | D-dimer ≥ 250 μg/L while anticoagulated | 1 point |

| O | Obesity with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 1 point |

| O | Older age, i.e. ≥ 65 years | 1 point |

| . | Predictor . | Scoring . |

|---|---|---|

| H | Hyperpigmentation | 1 point total, if any one of these criteria is present |

| E | Edema | |

| R | Redness of either leg | |

| D | D-dimer ≥ 250 μg/L while anticoagulated | 1 point |

| O | Obesity with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 1 point |

| O | Older age, i.e. ≥ 65 years | 1 point |

Decision Making: Women: 0-1, discontinue anticoagulation; ≥2, continue anticoagulation. All men: continue long-term anticoagulation.

In Brief

To discuss and decide with the patient who has a VTE how long to treat with anticoagulation, we use the recurrence triangle depicted in the Figure. In patients at intermediate risk of recurrence (patient “B”), situations where we or the patient is ambivalent as to whether to stop anticoagulation, or in women with true unprovoked VTE with a strong preference to come off anticoagulation, we use the D-dimer as an aid in decision making. It is also this group of patients in which we contemplate obtaining a thrombophilia work-up, as finding a strong thrombophilia predicts a higher risk of recurrent VTE (i.e., moves the patient down in the recurrence triangle). However, caveats are that strong thrombophilias are uncommon and a large number of patients would need to be tested to find one case of a strong thrombophilia, and some discrepant data exist on what truly constitutes a “strong thrombophilia.”

Finally, we do apply the HERDOO2 score to women in the intermediate risk of recurrence group in the triangle to see whether it matches the decision making that we arrive at with the D-dimer result (± strong thrombophilia) alone. However, none of the predictors of VTE recurrence should be used dogmatically or with too much confidence in the predictor’s validity, given the number of limitations discussed above.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Houghton and Dr. Moll indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.