The Question:

How do you approach giving bad news to patients and their families?

The Response:

Doug had essential thrombocythemia that eventually transformed into post-ET myelofibrosis. He required splenectomy 13 years ago. His thrombotic diathesis, refractory to warfarin, was controlled with enoxaparin or fondaparinux for the next decade. With time, he developed increasing circulating blasts. and year after year, we kept expecting transformation to acute leukemia. Now a frail 76-year-old, Doug and I had talked several times about this possibility. He became transfusion-dependent, but throughout the next six months, he continued to enjoy work in his yard.

When he bled spontaneously into his arm, fondaparinux was reduced. A week later, he bled into the retroperitoneum. With the patient hospitalized and hypotensive, we transfused while exploring angiography. He looked like hell. And I was late for heme-onc clinic. Years ago, I would have encouraged him to “hang in there,” reassuring him that he was under excellent hospitalist care, and pledging to return that evening. I now recognize, however, that this was inadequate. For this probable impending disaster, I had to “break the bad news” openly and prepare him and his wife.

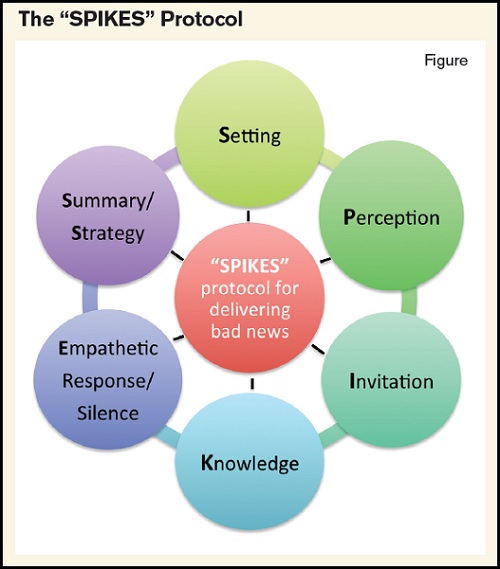

As hematologists-oncologists we break bad news frequently — diagnosis, recurrence, progression, incurability, prognosis, impending death — but most of us have had little formal training in this area. Dr. Walter F. Baile and colleagues1 taught a wonderfully useful approach called “SPIKES,” which I have outlined and modified in this article.

Setting

If at all possible, never give bad news by phone or in the hallway. Sit, with TV and cell phones off. It may require having other family members present, as well as extra chairs. Pull your chair close to the patient’s bed or chair, nonverbally signaling your connection and your therapeutic alliance, perhaps holding a hand or touching an arm, making sure you face both patient and family, and using eye contact as you speak. At this point, we are setting the stage.

Perception

Ask the patient and family what they think is going on. This simple act engages them (a critical element in good communication) and sends the message that what they think matters, such that we start with their perception of the situation. Furthermore, in this way we’re more likely to reframe or educate successfully, especially if any misunderstandings are openly expressed first.

Invitation

This simple step, however phrased (e.g.,“Shall I share the results of the scan with you now?” or “Is this a good time to tell you what I believe is happening?”) shows respect, focuses attention, and essentially asks for permission. We are about to announce something unpleasant. We may disappoint and occasionally devastate the recipients of the news we are about to deliver. Do it gently and with humility. Many patients and families feel “violated” when we tell them terrible things, so obtaining permission first signifies they’ve agreed to hear it and are ready to allow us into their world.

Knowledge

When it is time to break the news, patients and families benefit from a brief summary of what we knew (or thought we knew), what we hoped for, and finally, what we have now learned. Speak slowly, make eye contact, use simple terms, and if you must use medical jargon, translate as you go. Beware of providing too many details, and gently but resolutely cut to the chase. Most patients, especially during emotionally charged times, are best served with clear, nonmedical language. Then explain what the bad news means. If you pause after relating what the findings are, the patient and family may ask what the findings mean. In this way you have allowed them to once again invite you to tell more.

Empathic Response/Empathic Silence

This is new territory for many of us. After hearing bad news, patients and families often feel traumatized and overcome with emotion. Rather than speaking up, changing the subject, or moving to therapeutic options, a little silence is often best. Silence is powerful and valuable. When you do speak, an “empathic response” is your best move: Speak words that acknowledge that your patient is feeling something. The response may be a statement or question; go with what feels right at the time. For example:

“This must be very hard news for you to hear.” “I imagine this is very disappointing.” “Is this a big surprise, or did you kind of expect this?”

And our own feelings count as well:

“I’m so sorry, and I am really disappointed, too.” “I was also hoping we’d have more time.”

Try not to immediately shift away from the uncomfortable silence, the sadness, or the tears. This is how we process tragedy.

Summary/Strategy

Summarize, and decide where to go next. It may be treatment options, agreeing to meet next week, directly addressing prognosis, and/or discussing hospice care.

For Doug, the nature of our talk was my acknowledging and preparing for the very real possibility that, despite our best efforts, this could rapidly lead to demise and death, even today. We would do our best, but it looked bad. He and his wife understood, and months earlier we all agreed that heroics were not appropriate. In fact, he never got to angiography; that afternoon he passed away, before I finished clinic and with family at his side.

Dr. Baile and colleagues have written extensively on this important communication skill. “SPIKES” was published as a six-step protocol with attention to the oncology community in 2000.1 Our hematology patients get sick, receive bad news, and die. Yet the evidence suggests that palliative care services are underutilized in our field.2,3 Importantly, “palliative care” here refers to the days, months or years before hospice care, when symptom management, clarifying goals, advance care planning, and clear communication is so essential.

There are obstacles, of course, to implementing the “SPIKES” protocol. Hematologists often are in a rush, whether in clinic or on rounds in the hospital. Portals that allow patients direct access to their results online seem to enhance patient autonomy, but at the price of meaningful interpretation and context, and this can seriously undermine the doctor-patient relationship. The same is true of the electronic medical record if we’re trying to listen to and talk with patients. The most important elements, however, are our own levels of comfort with handling the intense feelings of the sick and vulnerable, and the extent to which we truly believe that the nuanced, challenging, and exceptionally important task of breaking bad news skillfully and sensitively is our responsibility.

As hematologists, we need to enhance our own palliative care skill sets, since most of the work falls on our shoulders. We should also be aware of an ever-increasing workforce of highly trained palliative care professionals who can assist us when the going gets rough, and when hematologic care becomes something much bigger — care of the critically ill human being, of the aggrieved family, and of the dying.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Hausdorff indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.