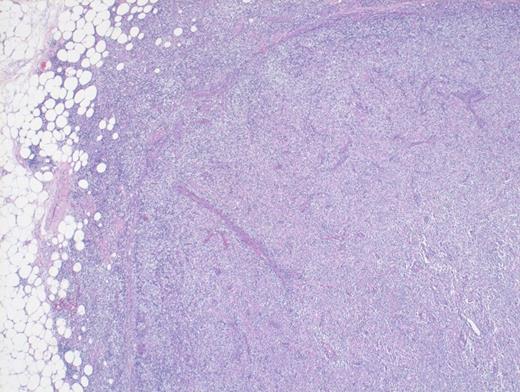

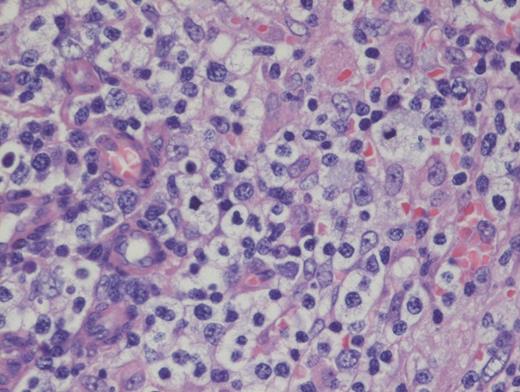

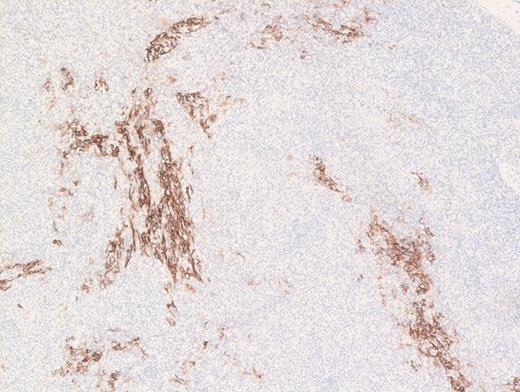

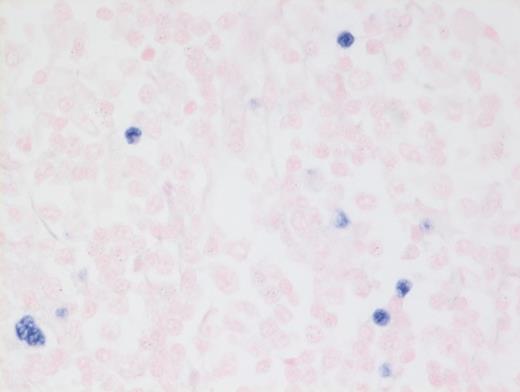

A 73-year-old woman with a history of autoimmune hepatitis presented with abdominal pain and fever. On further examination, the patient was noted to have hypergammaglobulinemia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and diffuse lymphadenopathy on imaging. An excisional biopsy of a superficial lymph node was performed. The images below are of a hematoxylin & eosin stain depicting architectural effacement by this proliferation of medium sized mononuclear cells (Figures A and B) containing numerous wisps of follicular dendritic cell meshworks (Figure C) and few scattered Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)+ cells (Figure D).

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain Depicting Architectural Effacement by this Proliferation of Medium Sized Mononuclear Cells.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain Depicting Architectural Effacement by this Proliferation of Medium Sized Mononuclear Cells.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain Showing Architectural Effacement by a Proliferation of Medium-sized Mononuclear Cells. Alternate view of hematoxylin and eosin stain depicting architectural effacement by this proliferation of medium sized mononuclear cells.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain Showing Architectural Effacement by a Proliferation of Medium-sized Mononuclear Cells. Alternate view of hematoxylin and eosin stain depicting architectural effacement by this proliferation of medium sized mononuclear cells.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain Showing Wisps of Follicular Dendritic Cell Meshworks. Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing wisps of follicular dendritic cell meshworks.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain Showing Wisps of Follicular Dendritic Cell Meshworks. Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing wisps of follicular dendritic cell meshworks.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain Showing a Few Scattered Epstein-Barr Virus+ Cells. FHematoxylin and eosin stain showing a few scattered Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)+ cells.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain Showing a Few Scattered Epstein-Barr Virus+ Cells. FHematoxylin and eosin stain showing a few scattered Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)+ cells.

A. Histiocytic sarcoma

B. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

C. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia

D. EBV+ large B-cell lymphoma

Sorry, that was not the preferred response.

Correct!

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is histologically identified by T-cells having ample clear cytoplasm in a background of prominent vasculature and a mixed inflammatory microenvironment (plasma cells, histiocytes, and immunoblasts). The process effaces the typical nodal architecture with retraction of the peripheral cortical sinuses, in addition to numerous new follicular dendritic meshworks outside of the follicles in the perivenular regions. There are numerous associated reactive B-lineage immunoblasts in the background in addition to the neoplastic T-cells.1 This specific case was positive for CD3 and CD4 on the clear cells.

Nearly all cases of AITL have EBV-infected B cells in the background that may proliferate unchecked due to the local immunodeficiency caused by AITL, or it may be a potential instigating factor, which, through antigen presentation, drives the T-cells to proliferate. It is important to note that the neoplastic T-cells themselves are not infected with EBV. These background EBV+ B-cells can transform into a second lymphoma such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma,2 and hence, the astute hematopathologist must remain vigilant to identify such concurrent B cell lymphoproliferations within AITL, which may benefit from addition of anti-CD20 therapy.

AITL now falls within the broader umbrella of nodal T-cell lymphomas with T-follicular helper (TFH) phenotype category proposed by the 2016 revision of the WHO classification.3 This broader umbrella category was proposed to include follicular T-cell lymphomas and other nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas with TFH phenotype, which sometimes mimic Hodgkin lymphoma with scattered Hodgkin-like cells in a lymphocyte-predominant background. Consistent with origin from TFH cells, AITL CD4+ T-cells are positive for TFH markers such as PD-1, CXCL13, and ICOS.

Option A is incorrect because histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is composed of very pleomorphic large cells, not medium-sized clear cells. Also, the observed CD21 meshwork pattern and presence of EBV would be inconsistent with HS. Option C is incorrect because the clinical presentation with elevated LDH and lymphadenopathy, and presence of EBV with CD21 meshwork proliferation are inconsistent with an extramedullary myeloid tumor such as myelomonocytic leukemia. Option D is incorrect. While EBV+ large B-cell lymphoma is a close differential diagnosis, most of the neoplastic cells in EBV+DLBCL, not otherwise specified (nos) are large and pleomorphic. Furthermore, EBV+ lymphoid cells in this entity are more numerous in comparison with AITL where the numbers of EBV+ lymphoid cells are much fewer. Also, the atypical extrafollicular CD21+ meshwork pattern observed in AITL is not seen in EBV+ DLBCL, nos. Sometimes, cases of polymorphous EBV+ DLCBL without diffuse large cells can be difficult to distinguish from AITL. Finally, option E is incorrect because follicular dendritic cell tumor would be expected to be diffusely positive for CD21 in a dendritic pattern, but the clear cells are negative for this marker, allowing for exclusion of follicular dendritic cell tumor as a diagnostic choice.

References

References

The authors indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.