Throughout the past 10 years, genomic analyses of myeloid neoplasms have uncovered a series of recurrent genetic alterations. While there is hope that these discoveries will result in novel molecularly targeted therapies, many of the genetic alterations identified are loss-of-function mutations that do not seem to be directly targetable. A prime example of this is TET2, which is affected by deletions and loss-of-function mutations in every type of myeloid neoplasm,1 in addition to being one of the most commonly mutated genes in clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP).2,3 The majority of TET2 mutations and deletions affect only one allele, and loss of even a single copy of Tet2 in mice results in aberrant hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) selfrenewal and an increased propensity for myeloid transformation.4

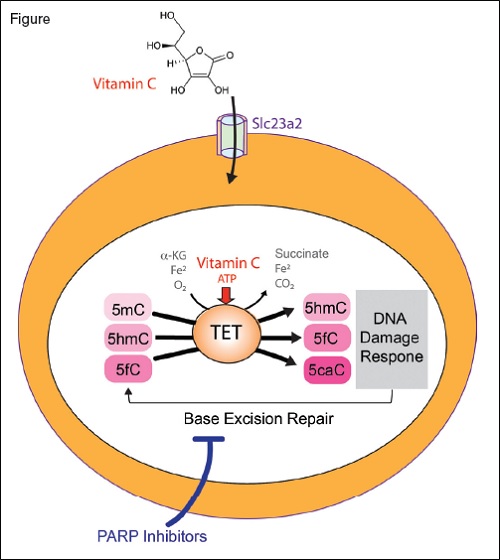

The TET enzymes are α-ketoglutarate and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenases that catalyze oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC). Loss of TET2, as commonly encountered in myeloid neoplasms and clonal hematopoiesis, results in aberrant hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. Treatment with vitamin C, a cofactor of α-ketoglutarate and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenases, restores TET enzymatic activity and suppresses leukemia formation (vitamin C enters hematopoietic stem cells via the transporter Slc23a2). Moreover, TET2 mediated DNA oxidation induced by vitamin C enhances sensitivity to PARP inhibition.

The TET enzymes are α-ketoglutarate and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenases that catalyze oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC). Loss of TET2, as commonly encountered in myeloid neoplasms and clonal hematopoiesis, results in aberrant hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. Treatment with vitamin C, a cofactor of α-ketoglutarate and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenases, restores TET enzymatic activity and suppresses leukemia formation (vitamin C enters hematopoietic stem cells via the transporter Slc23a2). Moreover, TET2 mediated DNA oxidation induced by vitamin C enhances sensitivity to PARP inhibition.

TET2 is a member of the TET family (TET1-3) of α-ketoglutarate and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenases that catalyze the iterative oxidation of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine, and 5-carboxylcytosine (Figure). These are key intermediates in the demethylation of DNA, and loss of TET2 is associated with hypermethylation of DNA. Recently, Dr. Luisa Cimmino and colleagues5 and Dr. Michalis Agathocleous and colleagues6 independently identified that treatment with vitamin C mimics TET2 function and restores hematopoiesis in mouse and human cells with TET2 deficiency. This discovery was based in part on prior observations that vitamin C promotes the activity of TET enzymes in culture.7 However, this finding had never been tested in vivo or in the context of hematopoietic cells.

Dr. Cimmino and colleagues first set out to address whether TET2 deficiency is necessary for maintenance of leukemia.7 Through use of a novel mouse model for reversible Tet2 knockdown, the authors identified that knockdown of Tet2 promoted myeloid transformation while restoration of Tet2 expression reversed aberrant HSC self-renewal. Moreover, Tet2 re-expression triggered a transient DNA damage response. This is likely because TET2 increases 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine, which modify cytosine that is removed by the base excision repair (BER) pathway (Figure). Given that PARP is an essential mediator of BER, the authors hypothesized that TET-mediated DNA oxidation induced by vitamin C would render cells hypersensitive to PARP inhibition. Consistent with this, the PARP inhibitor olaparib in combination with vitamin C resulted in greater cell killing of human leukemia cells in vitro than either agent alone.

Dr. Agathocleous and colleagues identified a critical role of vitamin C in regulating hematopoiesis in a TET-dependent manner in a very different way than Dr. Cimmino and colleagues. Through metabolomic analysis of HSCs versus more restricted progenitors, the authors found that both mouse and human HSCs are marked by high levels of vitamin C. This was found to be due to HSCs expressing nearly 20-times higher levels of the importer for vitamin C, Slc23a2, on their cell surface compared to more restricted progenitors (Figure). Depletion of vitamin C, by deletion of the enzyme required for vitamin C synthesis in mice (gulonolactone oxidase) combined with restriction of vitamin C intake, resulted in increased HSC frequency that could be reverted by reintroduction of dietary vitamin C. From a standpoint of malignant hematopoiesis, prior work has shown that loss of Tet2 collaborates with Flt3ITD mutations to promote transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in mice.8 Interestingly, vitamin C depletion also promoted leukemogenesis in Flt3ITD mutant mice and in mice with Flt3ITD mutation and haploinsufficiency of Tet2. Similar to the results seen by Dr. Cimmino and colleagues, vitamin C treatment to these models conferred antileukemic efficacy, even once AML was established.

In Brief

The above data identify that physiologic variations in vitamin C levels within tissues regulates HSC function and cancer initiation. Given the wide variability in vitamin C levels among individuals, these findings beg the question of whether dietary vitamin C levels might correlate with the risk of CHIP or leukemia. Moreover, both publications identify that high dose intravenous vitamin C treatment may be a novel therapeutic approach for clonal hematopoietic conditions associated with TET2 deficiency. Finally, these data have motivated the development of clinical trials combining high dose intravenous vitamin C with PARP inhibitors for the treatment of leukemia.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Abdel-Wahab indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.