Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common form of leukemia in the United States in terms of incidence and is a major area of unmet medical need among hematologic malignancies. Although five-year survival rates for adults with AML have increased in the United States per decade since 1975, the overall five-year survival rate in AML remains at 25 to 29 percent. Moreover, in prior years, the majority of therapeutic advances for AML have not come from the introduction of novel therapeutics but rather from optimizing use of older drugs, such as the use of high-dose cytarabine in consolidation therapy1 and an increased dose of daunorubicin for induction therapy.2 These facts were particularly disappointing given that our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of AML increased immensely throughout the past 10 years.

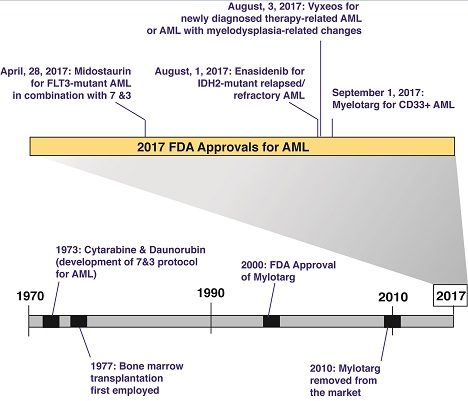

Fortunately, 2017 brought stellar progress in AML, with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approving four new therapeutic options for the disease (Figure). Two of these four new therapies are molecularly targeted therapies approved for patients with specific genetic abnormalities.3,4 There was also the first FDA approval of a drug for therapy-related AML (t-AML) and AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (AML-MRC) — subtypes of AML that tend to be associated with the most adverse outcomes.5 A brief summary of these new FDA approvals for AML and their exact indications are as follows:

Midostaurin for FLT3-mutant AML in combination with cytarabine and daunorubicin induction and cytarabine consolidation. Nearly one-third of AML patients bear an activating mutation in FLT3, and FLT3-mutant AML is a known adverse prognosticator. The clinical trial that led to approval of this drug required screening nearly 3,300 patients in order to randomize just more than 717 to treatment — a massive endeavor. The approval of the first FLT3 inhibitor in AML represents an exciting advance to upfront therapy and augurs great hope for the many additional FLT3 inhibitors in ongoing AML trials.

Enasidenib for adults with relapsed or refractory AML with an isocitrate dehydrogenase-2 (IDH2) mutation. Nearly 10 percent of AML patients bear a neomorphic mutation in IDH2. The approval of an inhibitor of mutant IDH2 is therefore conceptually novel and provides hope that inhibitors of mutant IDH1 may also be successful in AML. Interestingly, a major consequence of therapy seems to be a differentiation syndrome, not unlike the one that can occur with the use of all-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia.

CPX-351 for newly diagnosed t-AML or AML-MRC. Vyxeos is a liposomal formulation that delivers a fixed-ratio of daunorubicin and cytarabine. Its approval is owing to the results of a phase III clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of CPX-351 compared to standard cytarabine and daunorubicin induction in 309 patients 60 to 75 years of age with newly diagnosed t-AML or AML-MRC5 and demonstrated an improvement in overall survival in this difficult-to-treat cohort.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin for newly diagnosed CD33-positive AML in adults and for relapsed/refractory CD33-positive AML in adults and pediatric patients who are at least two years of age. This drug was previously approved for AML in 2000 and then removed from the market in 2010 because of failure to confirm prior efficacy data, as well as due to safety concerns. However, the current approval is for a lower recommended dose and schedule than what the FDA approved previously and is aimed at a different patient population. Approval of gemtuzumab in combination with chemotherapy was based on ALFA-0701, a randomized phase III study of 271 patients with newly diagnosed, de novo AML aged 50 to 70 years.6 Approval as a single agent was based on the results of two additional studies: AML-19, a randomized phase III study comparing gemtuzumab to best supportive care,7 and MyloFrance-1, a phase II single-arm study of AML patients in first relapse.8

Timeline of U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies in acute myeloid leukemia, highlighting progress in approvals for 2017.

Timeline of U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies in acute myeloid leukemia, highlighting progress in approvals for 2017.

These new FDA approvals for AML seem to represent the beginning of a trend — the arrival of the last several decades’ of biomedical research on this disease to the clinic. Four new agents gives the impression of an incredible amount of progress considering the number of previously approved therapies for AML in the past five decades (Figure). Moreover, as noted above, several of these treatments provide great hope that additional therapies targeting further molecular abnormalities in AML may also be forthcoming. Finally, several of these abnormalities (such as mutations in FLT3 and IDH2) are seen in myelodysplastic syndromes and other myeloid leukemias related to AML, leading to anticipation that there will be a role for such therapies, and therefore hope that they may yield progress in these diseases as well.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Abdel-Wahab indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.