A year is a long time in hematology. On December 28, 2017, Dr. Sattva S. Neelapu’s article in the New England Journal of Medicine reported on the phase II ZUMA-1 trial of CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) for patients with refractory large B-cell lymphoma.1 Patients with refractory disease were given CD19-targeted CAR T cells after receiving a conditioning regimen of low-dose cyclophosphamide and fludarabine (n=111). A response rate of 82 percent was reported, with 40 percent of patients still in complete remission (CR) at 15 months. The last 12 months saw a lot of activity in this area, with an updated report on this cohort, a second landmark trial leading to an additional licensed product, and a flurry of laboratory and clinical innovation. So how does the landscape for CAR-T treatment of lymphoma look in December 2018?

It is certainly true that the clinical outlook for patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma is poor with conventional therapies. The SCHOLAR-1 study is frequently quoted in CAR-T studies. SCHOLAR-1 was an international retrospective study of salvage therapy outcomes in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who had aggressive B-cell lymphoma resistant to chemotherapy, or who relapsed within 12 months after autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). An objective response rate of only 26 percent was observed, with a complete response rate of 7 percent and a median overall survival (OS) of 6.3 months. It is against this rather bleak landscape that CAR-T therapies are being compared.

A good place to start at the end of this year is with the updated report on the ground-breaking ZUMA-1 trial. First, we must remember the pathological criteria for recruitment, which were large B-cell lymphoma including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL), and transformed follicular lymphoma (FL). Furthermore, patients had refractory disease, which was defined as progressive or stable disease, as the best response to the most recent chemotherapy regimen or disease progression or relapse within 12 months after ASCT. Therapy with axi-cel was deliverable to 91 percent of enrolled patients, and the median time to delivery after leukapheresis was an impressive 17 days. These results led to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of axi-cel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma including DLBCL, PMBCL, transformed FL and high-grade B-cell lymphoma after at least two lines of systemic therapy.

The important aforementioned report by Dr. Neelapu and colleagues extends the median follow-up from 15 to 27 months and is now one of the longest studies of CAR-T therapy.2 How much changed in 12 months? The answer, perhaps encouragingly, is “not very much.” Clinical responses to CAR-T therapy are concertinaed into a short period such that the response at three months is highly predictive of long-term outcome. This reflects the startling speed by which clinical responses, and indeed adverse effects, can be observed following CAR-T infusion. The median time to response is one month, and some of the immunologic observations are rather dizzying, with T cells expanding up to 10,000 times and mediating a peak CAR-T expansion within the first 14 days. It has been estimated that each infused cell may kill up to 100,000 tumor cells, and as such, it is perhaps not surprising that long-term survival or exhaustion of the product can represent a challenge. However, this may not even be required, as a few months of CAR-T survival may be enough.

Against the backdrop of this rapid immunologic barrage against the tumor, it is encouraging that long-term CRs are seen at 27 months. Overall 37 percent of patients remained in an investigator-assessed CR at this timepoint. The median duration of response was 11.1 months with a median OS that was not reached, but that was estimated at more than two years, and a median progression-free survival of nearly six months.

The second CAR-T product that has been developed for aggressive lymphoma is the tisagenlecleucel product that was assessed in the JULIET trial supported by Novartis.3 The best CR rate was 40 percent, and the product is now licensed for relapsed or refractory lymphoma following FDA approval on May 1, 2018. The clinical indication is for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma including DLBCL, transformed FL, and high-grade B-cell lymphoma after at least two lines of systemic therapy. Further down the line, encouraging results are also being reported with lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) from Juno in the TRANSCEND trial. This CAR-T product utilizes the CD137 co-stimulatory domain but sets the CD4:CD8 ratio of the CAR-T infusion at 1:1.

CAR-T therapy will change many approaches in the management of aggressive lymphoma. Remarkably, responses seem largely unrelated to pathological or clinical features such as lymphoma subtype, germinal center B-cell and activated B-cell DLBCL, refractory subgroups, low and high International Prognostic Index (IPI), and bulky or extranodal disease. It almost seems that if T cells can be appropriately expanded and maintained in vivo, they will kill B-cell tumors irrespective of phenotype, genetics, or tumor bulk.

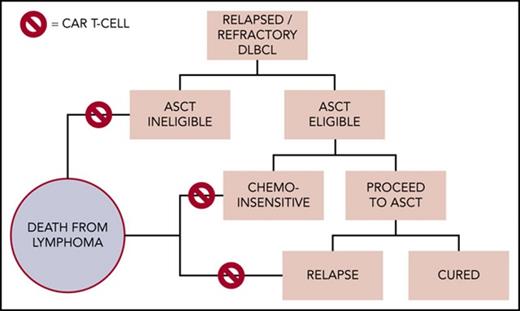

Potential clinical application of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy within the management of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in 2018. From Chow VA, et al. Translating anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy into clinical practice for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018;132:777-781. ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation.

Potential clinical application of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy within the management of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in 2018. From Chow VA, et al. Translating anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy into clinical practice for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018;132:777-781. ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation.

The currently positioning of therapy in the management of large B-cell diffuse lymphoma is in patients who have failed initial therapy and do not achieve a good response to successful salvage chemotherapy and subsequent autograft. Dr. Victor A. Chow and colleagues have suggested how cell therapy may fit into the 2018 algorithm of DLBCL therapy although some of these decision points currently need further evidence (Figure).4 This is already a large group of patients and will bring CAR-T therapy into the therapeutic armamentarium of most hematologists. The potential implications for clinical delivery are profound and if many centers are unable to administer such products, it may centralize delivery of care.

Of course, there are considerable toxicities with CAR-T. The two major acute toxicities are cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity. These are now managed according to standardized regimens and although grade 3+ CRS and neurotoxicity adverse events were seen in 13 percent and 31 percent of patients respectively in ZUMA-1, these are typically reversible.

The profile of clinical response for CAR-T therapy of relapsed large B-cell lymphoma that emerges at the end of 2018 consists of a sustained CR of 30 to 40 percent. When compared to the median survival of just six months in the retrospective SCHOLAR-1 study, the results are stunning but still leave 60 percent of patients with a poor outcome. Treatment failures can relate to inadequate expansion of the infused product, loss of CD19 on the tumour cell, or local immune suppression such as increased PD-L1 expression. Huge research programs are currently addressing all three of these challenges.

So, how do we proceed with CAR-T in large cell lymphoma? Phase III randomized trials are already underway to directly compare the efficacy of CAR-T therapy with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous transplantation after first relapse. At some point, they will enter first-line therapy for patients with high-risk features. Inevitably they are also being assessed in the indolent lymphomas. A year may seem like a long time in hematology, but progress in CAR-T biology and therapy works to a much shorter timeframe.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Moss indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.