The Cases

Case 1

A 24-year-old woman presents with cervical lymphadenopathy and night sweats. An excisional lymph node biopsy confirms classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Positron emission/computed tomography imaging and laboratory testing indicate stage IIIB disease with an International Prognostic Index score of 4. Her hematologist is recommending escalated-dose BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone). She is interested in fertility preservation and she feels well.

Case 2

A 30-year-old woman reports blurry vision and on further evaluation is found to have splenomegaly (8 cm below the left costal margin), leukocytosis, and anemia (WBC, 25,000/µL; Hgb, 9.9 g/dL; platelets, 289,000/µL). Review of the peripheral blood smear reveals a leukoerythroblastic picture, with all stages of maturation present in the myeloid lineage, and 1 percent blasts on manual differential. Cytogenetic testing demonstrated the presence of t(9;22)(q34;q11). Bone marrow evaluation confirmed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Her hematologist recommends initiation of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. She asks if this treatment will affect her ability to become pregnant, as she was considering pregnancy in the next 12 to 24 months.

Case 3

A 16-year-old girl is noted to have pallor and reports excessive fatigue. On presentation to her pediatrician, she has leukocytosis, anemia, and thrombocytopenia (WBC, 17,400/µL; Hgb, 8.9 g/dL; platelets, 64,000/µL). A bone marrow biopsy demonstrates precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Cytogenetic and molecular studies are normal, and her cerebrospinal fluid demonstrates no evidence of leukemia. Her hematologist is planning to initiate therapy on a pediatric ALL clinical trial with a typical backbone of primarily anti-metabolites and low doses of anthracycline and cyclophosphamide. She has not considered her wishes for reproductive options in the future.

Case 4

A 28-year-old woman has noted progressive shortness of breath and bruising. She was planning to discuss these symptoms with her primary care physician, but she developed a fever to 103°F and felt unwell, so she presents to urgent care for evaluation. On examination, she is pale and tachycardic with hypoxemia (oxygen saturation 91% on room air), swollen gums, and numerous ecchymoses. Laboratory data include WBC, 143,000/µL; Hgb, 6.2 g/dL; and platelets, 18,000/μL. Immature cells are noted on the differential, and she is transferred to the emergency department of the nearby hospital, where additional evaluation confirmed the presence of 86 percent blasts in the peripheral blood. Bone marrow testing reveals a diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML; not otherwise specified; with monoblastic differentiation, French-American-British subtype M5a). Prothrombin time was prolonged at 15.6 seconds, fibrinogen was 89 mg/dL, and D-dimer was 10.67 µg/mL.

The Question

How should young women who are newly diagnosed with hematologic malignancies be counseled and managed regarding fertility preservation?

The Responses

Hematologists should address with all patients the possibility of reproductive harm associated with treatments for blood cancer.1-3 Standard-of-care options for preserving fertility in women include oocyte or embryo cryopreservation.4,5 Experimental options such as ovarian tissue cryopreservation6,7 or ovarian in vitro maturation8,9 may be appropriate in some scenarios; ovarian tissue cryopreservation is currently the only option available to prepubertal girls.

Pursuit of oocyte or embryo cryopreservation requires a period of 10 to 14 days of hormonal ovarian stimulation, followed by oocyte retrieval via a transvaginal approach.10,11 Hence, patients must be clinically stable enough to delay cancer-directed therapy. The decision about whether to cryopreserve oocytes versus embryos is a personal one for the patient. While embryo cryopreservation is associated with slightly higher live birth rates, this procedure requires a male partner (or willingness to use donor sperm) and no ethical objections to the freezing and storing of embryonic tissue. Hence, for some women, oocyte preservation may be preferable.

Case 1

This patient is anticipated to receive high-dose alkylator-based therapy, which carries a high risk of permanent infertility and is certainly associated with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), a condition defined as cessation of menstrual periods due to ovarian failure at a young age, typically under the age of 40.12-14 She is otherwise clinically well. There is little to no harm in delaying her chemotherapy for approximately two weeks. She should be referred urgently to gynecology/reproductive endocrinology for consideration of oocyte (or embryo) cryopreservation. In this circumstance, facilitated referrals are essential for the best care of the patient. Hematologists should cultivate relationships with their colleagues in reproductive endocrinology through educational opportunities (such as grand rounds or multidisciplinary conferences) and other collaborations; dedicated referral lines and social workers or patient navigators can be indispensable in securing expedited appointments.15-17

Case 2

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) are U.S. Food and Drug Administration pregnancy category D drugs. Hence, this young woman has a few options to consider: 1) initiate therapy with a high-potency TKI (e.g., nilotinib) with hope of achieving a rapid molecular response, then holding the TKI while attempting to conceive, and resuming TKI after delivery (assuming she has not met criteria for treatment-free remission); 2) retrieve oocytes now (or during TKI therapy) and plan for pregnancy using a gestational carrier; or 3) attempt pregnancy now, prior to initiating therapy, with very close hematologic monitoring and consideration of interferon alfa if needed.18

Case 3

Typical ALL regimens, particularly pediatric protocols, carry little risk of inducing permanent amenorrhea4 ; risk of premature ovarian insufficiency is less well described. This young woman should be counseled about the small risk of reproductive harm, but probably does not require specific fertility interventions. After treatment is completed, she should be referred to gynecology for fertility assessment and counseled about the possibility of POI. She may consider cryopreservation of oocytes in the future if her childbearing is delayed.

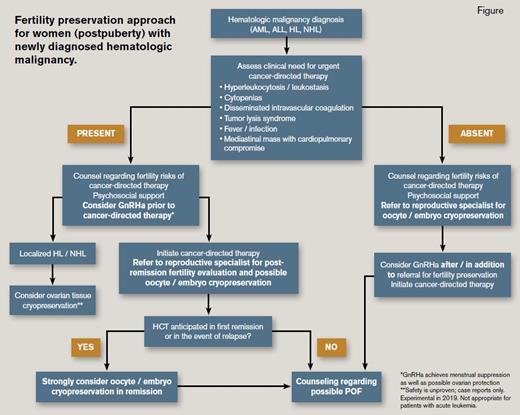

Fertility preservation approach for women (postpuberty) with newly diagnosed hematologic malignancy. Reprinted from Loren et al. Blood. 2019;134:746-760.

Fertility preservation approach for women (postpuberty) with newly diagnosed hematologic malignancy. Reprinted from Loren et al. Blood. 2019;134:746-760.

Case 4

This patient is critically ill with disseminated intravascular coagulation, leukostasis, and likely sepsis. It is not appropriate to delay her therapy; on the contrary, emergency interventions are required to manage her AML (Figure).19,20 She should be counseled about fertility risks with AML therapy, which is infrequently associated with permanent amenorrhea.4 Consideration should be given to administering a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (GnRHa) such as leuprolide to achieve menstrual suppression prior to induction. A GnRHa may also induce some measure of ovarian protection, and while data are scant, a GnRHa is unlikely to cause harm in this regard.21,22 Although ovarian tissue cryopreservation may be done immediately as experimental therapy, this technique is contraindicated in patients with acute leukemia owing to the concern of transmitting leukemic cells back to the patient when the thawed tissue is re-implanted after completion of therapy.23-25 After achieving remission, this young woman should be referred to gynecology for oocyte/embryo cryopreservation. This may occur prior to or during consolidation therapy,26 but should definitely be done prior to hematopoietic cell transplantation, if transplantation is part of her treatment plan.

Although not all women will be able to receive a fertility preservation intervention, fertility risks should be discussed with each patient prior to initiating therapy, as patient’s preferences regarding treatment may be influenced by their perceptions about fertility risk.27 Engaging in shared decision-making can reduce distress and improve quality of life even when patients do not pursue fertility preservation.3

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Loren indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.