When I see patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma (FL) in clinic, I usually tell them their disease is not curable but very treatable, and can be successfully managed over a long period. I tell them their prognosis is very good, that they will live a long time, and that they should not run home and spend all of their retirement money. This usually gets a chuckle and breaks some of the tension surrounding this initial encounter. But am I telling them the right thing? I have worried about this for years. Classic teaching is that FL is incurable. I certainly have seen patients relapse after 15 or 20 years, but I also have patients who have been in remission for 15 or more years. Are they cured? Because of the peculiar natural history of FL, it is hard to know when, if ever, you can declare someone cured. As a result, I am afraid to say it. I suppose I am afraid the patient will be upset with me if I declare it and turn out to be wrong. A recent publication has me again thinking about this difficult question.

Long-term follow-up from the PRIMA study was recently published. To refresh your memory, PRIMA was a phase III randomized clinical trial evaluating the benefit of maintenance rituximab in high-tumor-burden FL. Enrolled patients were non–randomly assigned to one of three immunochemotherapy regimens, including R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone), or R-FCM (rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone). Responding patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 fashion to receive two years of rituximab maintenance (a single dose every 8 weeks for 2 years), or to an observation arm. In the original publication, with three years of follow-up, a large progression-free survival (PFS) benefit was seen in patients assigned to maintenance, with three-year PFS rates of 75 percent compared with 58 percent in patients assigned to observation. No overall survival benefit was demonstrated, but the improved PFS did translate into longer time to next treatment. Maintenance was associated with some increased risk for infection, but the magnitude of the risk was relatively small. Based on these results, rituximab maintenance was widely adopted as standard of care around the world.

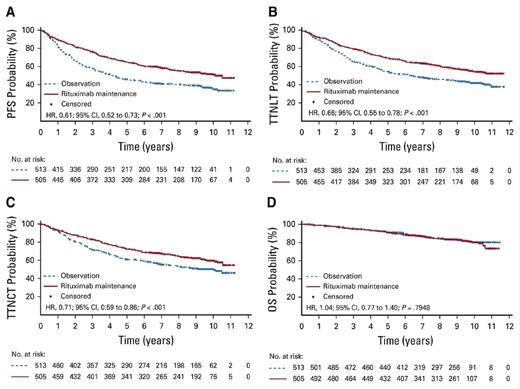

"Kaplan-Meier estimates of (A) progression-free survival (PFS), (B) time to next antilymphoma treatment (TTNLT), (C)

"Kaplan-Meier estimates of (A) progression-free survival (PFS), (B) time to next antilymphoma treatment (TTNLT), (C)

The updated data now have nine years of follow-up, and of the original 1,018 patients randomly assigned, 607 have available data. The loss of data from 400 patients immediately raises some concerns about the reliability of the analysis. Admittedly, collecting high-quality long-term follow-up data is a huge challenge for any clinical trial. The authors provided baseline characteristic data for the original 1,000 patients, the 600 with extended follow-up, and the 400 without extended follow-up. The extended follow-up cohort seems to be adequately representative of the larger cohort. The take-home message from the extended follow-up analysis is that the PFS benefit of rituximab maintenance is maintained over time. The 10-year PFS estimates were 51 percent in the rituximab maintenance arm and 35 percent in the observation arm (Figure). This means that 50 percent of the patients with FL who have high tumor burden have not relapsed or died 10 years after receiving initial therapy — an impressive result by any standard.

In Brief

Are the patients cured? I wish I knew. But let’s imagine for a minute that they are. If true, it prompts the question as to whether the entire approach to FL should be re-examined. Typically, patients with low tumor burden are observed without treatment until they develop symptoms or high tumor burden. If R-CHOP plus maintenance rituximab is successfully treating 50 percent of patients with high tumor burden, then that number should be even higher if applied to those with low tumor burden. So perhaps we should be offering patients the very best treatment we have on day 1, and retire watch and wait. Of course, this needs to be studied prospectively. I would limit such a trial to younger patients with FL (65 years and younger), since the disease is unlikely to affect the lifespan of older patients. It would take a bold study, committed to 20 years of careful long-term follow-up. I think such a study should be done … by a young investigator. Finally, in the interest of full disclosure, these thoughts I am espousing are not new or original. Several luminaries in the field (Drs. James Armitage, Fernando Cabanillas, and Richard Fisher, to name a few) have argued for curability for years. I am wondering if they were right all along.

Competing Interests

Dr. Kahl indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.