For the lucky, war is often a distant tragedy. No matter how compelling the headlines, for most of us reading this, it is probably difficult to imagine life in a country that is under attack. Not so for Dr. Sergiy Klymenko.

Dr. Klymenko is a hematologist and professor at the Feofaniya Clinical Hospital in Kyiv who normally specializes in the care of patients with acute and chronic hematologic malignancies. Since the Russian invasion of his country in February 2022, however, Dr. Klymenko has become an expert on the effects of war on patients with cancer. He recently presented at the European Hematology Association (EHA) Congress on the challenges faced by patients with cancer living in Ukraine.

The first thing to recognize, Dr. Klymenko said, is that in a country as large as Ukraine, the effects of the war vary based on location and timeline. “When the invasion started, a lot of people were in the fighting theater,” he recalled, noting how much of the country was under attack in February. “These patients immediately lost the possibility to be properly treated. It was risky to move [them] to a hospital through occupied areas.”

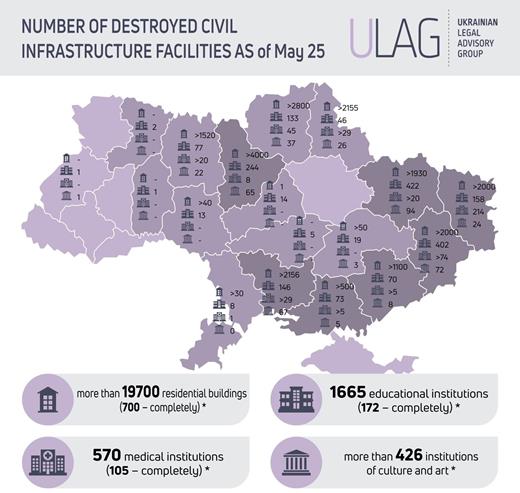

As the invasion has progressed, the impact has become greater than direct harm to patients, but also includes the consequences of infrastructure loss (Figure). As Dr. Klymenko told us, as of May 2022, there have been more than 570 medical institutions damaged by the bombings and attack, the majority of which are in the eastern and southern edges of the country.

Source: Ukrainian Legal Advisory Group. *Data obtained from open sources.

Source: Ukrainian Legal Advisory Group. *Data obtained from open sources.

The other tremendous impact, which began as soon as war broke out, was the rapid and massive movement of populations. “From the first day of the war, displacement began,” said Dr. Klymenko. “Patients, their families … they began to move to safer places. Currently, there are approximately 6.5 million refugees abroad, and we also have a lot of internally displaced people. For medical care, the movement abroad isn't necessarily bad for patients, because where they moved, they may obtain the proper care,” he explained. “But for others, they may have lost their chance at rapid care and are no longer with their families.” It is not just the patients and families who have left, but also physicians and other health care workers, creating imbalances between where physicians are needed and where they are.

A recent survey reported that 25 percent of all patients with cancer have left Ukraine in order to continue to get care for their diseases elsewhere in Europe. The most noted impact on their care, according to this same survey, is difficulty obtaining medications due to logistical barriers to transportation, delivery, and administration of cancer therapy. And it is not just cancer chemotherapeutics that are scarce. Dr. Klymenko pointed out that diagnostic and laboratory reagents are also difficult to obtain in some instances and that many of the smaller diagnostic labs have shut down, leaving only large conglomerate labs available to perform testing. “It is hard to perform even basic imaging or laboratory testing in some parts of the country,” Dr. Klymenko said. “There has been a stop to most transport of radiopharmaceuticals due to transportation risks and destruction of radiologic facilities.”

While many of these challenges seem insurmountable, Dr. Klymenko remains optimistic that Ukrainian hematologists and their patients will get the support they need. For example, he indicated that support in the form of medication, reagent, and device donations through governmental hubs might be helpful in some cases. However, some specialty medications for orphan diseases may be best donated directly to hematology clinics rather than to the government, since these are the locations where patients are likely to be known and in need of these unusual medications. Given the severe shortage of hematology care providers currently in certain areas of the country, Dr. Klymenko proposes video conferences and virtual tumor boards to support the patients still living under war-impacted conditions.

Another concern of Dr. Klymenko is the high likelihood of long-term damage to the educational systems in Ukraine, including medical and specialty education. He believes we should be thinking now about how the international hematology community might support targeted educational opportunities for Ukrainian hematologists, open calls for joint research projects with Ukrainian teams, or prioritized funding for projects that emerge from Ukraine or that cover an area applicable to the current situation, such as postwar hematologic disorder epidemiology or advances in the use of telemedicine during armed conflict. These are just a few of the proposals Dr. Klymenko made during his recent presentation at the 2022 EHA Congress.

Dr. Klymenko himself is back to work these days – seeing patients, and also working to help those of us outside of the zone of conflict understand what we might do to help.

Competing Interests

Dr. Michaelis indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.