Twenty years ago, The Hematologist featured a review of the treatment of acute leukemia in older adults.1 At that time, the treatment arsenal for this population remained mostly stagnant, as did the dismal survival rate.

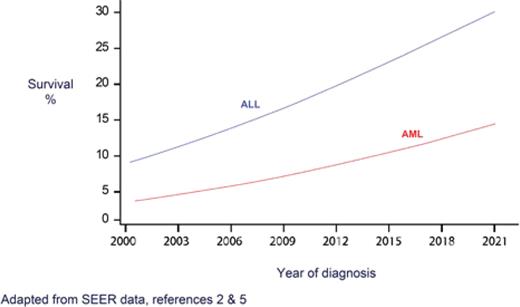

Since then, dramatic progress in the treatment of acute leukemia has particularly impacted the older population, both in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL) (Figure). In AML, with a median age at presentation of close to 70,2 the overall survival (OS) rate among older patients had been in the single digits for decades, with only modest improvement observed over the years.3 Now, for the first time, a recent analysis from Sweden reports a five-year survival rate of 20% for patients aged 70-79, and 40% for those aged 60-69.4 In ALL, five-year OS for patients over age 65 has hit a record-breaking rate of approximately 25%.5,6

Five-year survival of acute leukemia, age >65 years

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoid leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

Five-year survival of acute leukemia, age >65 years

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoid leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

What are the factors that led to these transformative changes? First, as fitness levels and life expectancy rates continuously rise, an average 75-year-old is healthier than in the past,7 presumably allowing for the administration of more intensive therapies. Second, and no less important, improvements in supportive care account for better outcomes, particularly in reduced treatment-related mortality. Third, the advent of targeted therapy has introduced non-intensive treatment options and durable responses without the need for myeloablative chemotherapy.8,9 Finally, progress in transplantation has revolutionized the field of post-remission therapy, with greater donor availability and improved conditioning regimens.10 Below, we briefly discuss a few remarkable examples.

Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Back in the 1980s, the outcomes for older adults with AML were so poor that the utility of any therapy was debated. One phase III, randomized study had demonstrated improved OS with the use of intensive induction, albeit with a still-bleak outcome (21 weeks vs. 11 weeks).11 Furthermore, despite complete remission (CR) in more than 50% of patients, the majority relapsed, given the limited options for post-remission therapy at the time. Much has changed since then (Table 1).

Important issues in AML treatment for older adults

| Considerations . | Then . | Now . |

|---|---|---|

| Should standard intensive induction be offered to all patients? | Yes | Low-intensity induction preferred in patients older than 75, possibly younger |

| Targeted agents? | No | Can be added to induction, as in younger patients (also possible as single agent in unfit patients or in relapsed disease) |

| Once CR is achieved, how many cycles of intensive post-remission therapy should be given if not going to transplant? | 0-1 | 2-4 (with age-adjusted dosing) |

| Allo-HSCT post remission? | Very rare | Common |

| Treat relapsed disease? | Rare | Common |

| Considerations . | Then . | Now . |

|---|---|---|

| Should standard intensive induction be offered to all patients? | Yes | Low-intensity induction preferred in patients older than 75, possibly younger |

| Targeted agents? | No | Can be added to induction, as in younger patients (also possible as single agent in unfit patients or in relapsed disease) |

| Once CR is achieved, how many cycles of intensive post-remission therapy should be given if not going to transplant? | 0-1 | 2-4 (with age-adjusted dosing) |

| Allo-HSCT post remission? | Very rare | Common |

| Treat relapsed disease? | Rare | Common |

Abbreviations: Allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CR, complete remission.

Induction Therapy

Markedly reduced induction mortality in fit older adults compared to 25 years ago is encouraging patients and physicians to administer intensive induction, usually with a 7+3 regimen of anthracycline and cytarabine. At the same time, the most paradigm-changing addition to the treatment armamentarium is the ability to treat unfit older adults with the combination of a hypomethylating agent and the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax (HMA/ven). This combination12 is routinely administered to patients who are unfit for intensive chemotherapy or are over age 75. Many clinicians, particularly in the U.S., also consider this approach for fit adults over age 60 as an alternative to intensive induction.13 Treatment with HMA/ven can be so well-tolerated that it is offered even to patients over age 90.14 It is not uncommon to consider allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) after achieving remission with this regimen.13 There is also the possibility of an all-oral HMA/ven regimen.15 It should be noted that HMA/ven requires continuous courses of therapy, with recurrent cytopenias, and the treatment can be associated with significant morbidity. A recent study estimates that patients who receive HMA/ven may spend at least as many days in the hospital or clinic as those receiving intensive chemotherapy.16 Nevertheless, HMA/ven has revolutionized remission induction in older patients, with more than 60% response rates achieved with a low-intensity, tolerable outpatient regimen.

Consolidation

While the need for post-remission therapy was established 40 years ago,17 such an approach was not considered feasible for older patients. In fact, there were no unequivocal data demonstrating the advantage of any post-remission therapy. And, when administered, there was a reported lack of benefit beyond one cycle, according to the findings of one randomized study.18 Confounding this was the exaggerated notion, partly due to medicolegal considerations, of the toxicity of high-dose cytarabine (HiDAC), a cornerstone of consolidation therapy in young adults,19 when administered for multiple cycles. As post-remission therapy was often omitted or shortened for older adults, it is not surprising that most of these patients relapsed quickly. It was only at the turn of the century when HiDAC regimens for patients above age 70 were first described, with age-adjusted dose reductions,20,21 followed by widespread use among older adults.22 This practice has contributed to improved relapse-free survival.

Transplant

The current survival outcomes of older adults following allo-HSCT were unfathomable only two decades ago, with recent reports of three-year OS rates of 40 to 50% in select patients over age 60.10 The advent of reduced-intensity conditioning23 ameliorated some of the transplant-related toxicities and enabled allo-HSCT among older patients, including those with comorbidities. As the upper age limit of patients undergoing allo-HSCT continues to rise almost linearly every year, the number of patients aged 65 and older who have received transplants has more than doubled over the past decade, with relapse rates consistently decreasing.24

Acute Lymphoid Leukemia

The most dramatic advances in ALL are among the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)-positive subgroup, which comprise approximately 50% of B-lineage patients with ALL above age 606,25 (Table 2). The incorporation of targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors has transformed Ph-positive ALL from one of the diseases most feared by leukemia clinicians to one with increasingly improving survival rates. In a trial including adults aged 20-83 (38% above the age of 60) with Ph-positive ALL, combination of the bispecific T cell engager blinatumomab and ponatinib culminated in a frontline chemotherapy-free regimen, with an estimated three-year OS of 91%.26 The possibility of low-intensity therapy with chimeric antigen receptor T cells, blinatumomab, or the immunoconjugate inotuzumab has also provided great hope to B-lineage ALL patients with relapsed or refractory disease.8

Important issues in ALL treatment for older adults

| Considerations . | Then . | Now . |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic options for Ph+? | Dismal prognosis | TKI-based regimen, paradoxically now best possible subtype for an older patient |

| Immunotherapy? | None | Can incorporate bispecific antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates* |

| CAR-T therapy? | Science fiction | For relapsed ALL* |

| Allo-HSCT post remission? | Very rare | Occasionally |

| Treat relapsed disease? | Very rare | Common |

| MRD-directed therapy? | Occasionally | Standard of care |

| Considerations . | Then . | Now . |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic options for Ph+? | Dismal prognosis | TKI-based regimen, paradoxically now best possible subtype for an older patient |

| Immunotherapy? | None | Can incorporate bispecific antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates* |

| CAR-T therapy? | Science fiction | For relapsed ALL* |

| Allo-HSCT post remission? | Very rare | Occasionally |

| Treat relapsed disease? | Very rare | Common |

| MRD-directed therapy? | Occasionally | Standard of care |

*Primarily relevant to B-lineage ALL

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; Allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant; CAR-T, chimeric antigen T-cell; MRD, measurable residual disease; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome positive; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Although the treatment options for—and outcomes of— older adults with leukemia still lag far behind those of younger patients, the progress made over the past two decades is unparalleled in the disease’s history. At last, the notion of a cure for some is a dream come true. One can only hope that the next two decades will be just as fruitful, if not more so.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Yisraeli Salman received consultancy fees from Intellisphere, LLC. Dr. Rowe is a consultant for BioSight.