Editor’s Note: With this article, we introduce “Expanding Excellence,” a semi-regular series of articles that highlight the significance of bringing all backgrounds and experiences to bear in conquering blood diseases.

How do you incorporate social determinants of health factors into your clinical or research work? Why is this important?

Pediatric hematologic malignancies are among the most curable childhood cancers, with survival rates approaching 90% for many subtypes.1 However, these outcomes are not uniformly realized.2 Survival disparities persist for patients from minoritized groups and for those living in poverty or facing structural barriers to care.3 While disparities by ethnicity may be partly related to differences in disease or host biology, more often these disparities reflect systemic inequities in access, resources, and opportunity. Efforts to improve outcomes must therefore go beyond therapeutic innovation and address the social context in which children with cancer live and receive care.

Understanding Health Disparities and Social Determinants

The World Health Organization defines health disparities as avoidable differences in health status arising from the social conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.4 These conditions — collectively referred to as social or structural determinants of health (SDOH) — include factors such as income, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, social support networks, and access to health care.5 Structural determinants such as institutionalized racism and discriminatory policies further entrench the inequities related to social vulnerability. In pediatric oncology, such factors may influence when children present to care, whether they are enrolled in a clinical trial, how reliably they are able to adhere to therapy, and the degree of support available to their families throughout treatment and survivorship.4

The Cancer Continuum and Multilevel Barriers to Care

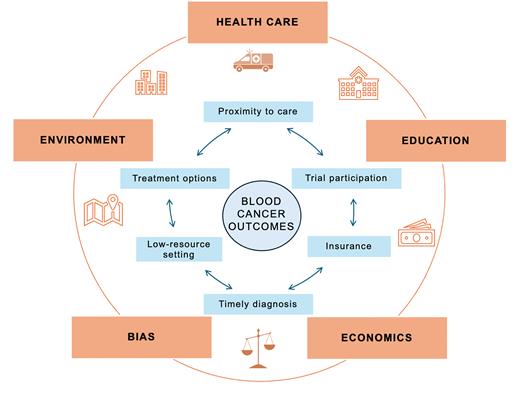

A useful framework for understanding disparities is the cancer continuum, which encompasses the care trajectory from diagnosis and treatment to post-treatment care and long-term survivorship. At each stage, inequities may arise from policies at the federal or state level (e.g., insurance eligibility), factors at the community level (e.g., transportation infrastructure), and factors at the institutional or individual level (e.g., provider bias or language-related barriers).6 As examples, lack of insurance or inadequate coverage may delay diagnosis or limit access to optimal therapy; rurality or difficulty with transportation may hinder someone’s ability to reach a large academic medical center for care; and limited translation services for consents or study documents may limit enrollment of patients who speak languages other than English (Figure).

Potential mechanisms through which access to care may mediate the effects of social determinants of health on blood cancer outcomes

Potential mechanisms through which access to care may mediate the effects of social determinants of health on blood cancer outcomes

A Translational Approach to Equity

A translational approach to health equity in pediatric oncology requires bridging the gap between research and clinical care. First, we must generate evidence that identifies where and why disparities occur. For example, recent studies in Hodgkin lymphoma have shown that Black and Hispanic patients are more likely to present with advanced-stage disease and are at significantly increased risk of death following relapse, even when controlling for upfront therapy and insurance status.7 Similar disparities have been reported in patients with acute leukemia2 and solid tumors.

We argue that to address inequities and improve gaps in care, health systems should implement systematic screening for SDOH akin to systematic screening for high-risk, cancer-related mutations. Screening tools can help identify unmet needs related to food insecurity, housing instability, financial strain, transportation, language barriers,7 and health literacy.8 However, screening alone is insufficient. It ideally should be followed by timely and targeted interventions that connect families with material resources,9 including, but not limited to, financial assistance, transportation services, social work support, and mental health care. This model requires institutional investment and interprofessional collaboration across disciplines.

Implementing SDOH Screening in Clinical Practice

Routine screening for SDOH should be integrated into oncology care from the time of diagnosis. Validated screening tools such as the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences10 or those embedded in electronic health records (EHRs) can help standardize the process. Screening should occur at key points, including diagnosis, the start of therapy, transitions in care, and survivorship planning. Clinicians and ancillary team members should ideally receive training in culturally competent communication to ensure that screening is conducted in a manner that builds trust and avoids stigma. Collaboration between medical providers and social work teams is critical to ensure best practices for screening, as well as to close the communication loop when patient needs are identified.

To be actionable, screening data must be linked to institutional pathways that facilitate referral and resource delivery. EHRs can be leveraged to trigger clinical decision support, auto-generate referrals, and facilitate billing through Current Procedural Terminology codes such as 96160 for health risk assessments. Collecting structured data on SDOH not only improves individual care but also enables health systems to identify population-level trends and allocate resources more equitably and expeditiously.

Call to Action

Oncology clinicians routinely collect and interpret data about tumor biology, laboratory values, and imaging. We must bring the same discipline to assessing the social context in which our patients live and receive care. Children and adolescents facing a cancer diagnosis rely on their care teams for both medical treatment and for support navigating complex systems. Identifying unmet social needs and connecting families to available resources should be considered core responsibilities of pediatric oncology care. Importantly, clinicians must also engage in broader efforts to advocate for systemic change — both within institutions and at the policy level — to dismantle the structural barriers that perpetuate disparities.

Conclusion

Achieving health equity in pediatric oncology requires a shift in both mindset and practice. High-quality care cannot be defined solely by treatment protocols and survival rates. It must also account for the social realities our patients face and the systems that shape their outcomes. By integrating SDOH into clinical and research workflows, and by advocating for structural change, we can move toward a future in which every child and adolescent with cancer has an equal chance to thrive.

Disclosure Statement

The authors indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Kahn is is supported by the Blood Cancer United Scholar in Clinical Research Award. The authors recognize that while terminology around social and structural determinants of health continues to evolve, the urgency of addressing cancer disparities in socially disadvantaged or vulnerable populations remains unchanged.