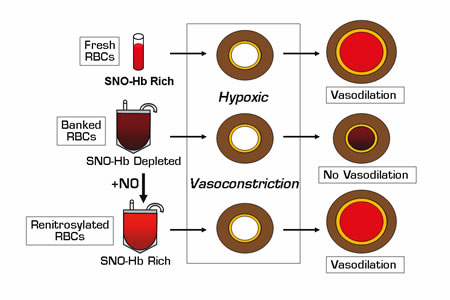

Tissue oxygen (O2) delivery is dependent on two interacting processes: red blood cell (RBC) O2content and microcirculatory blood flow. Under normoxic conditions, vasomotor tone and tissue perfusion are regulated by endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO). In hypoxic tissues, RBCs transfer bioactive NO to the vessel wall to cause vasodilation and increase oxygenation. The chemistry of NO biosynthesis and export from RBCs is not yet completely understood; however, the mechanistic roles of hemoglobin (Hb) have recently been clarified.1,2 Important intermediates in the process include S-nitrosothiol (SNO) adducts and S-nitrosohemoglobin (SNO-Hb), the concentration of which directly correlates with the ability of RBCs to transfer NO and induce vasodilation in laboratory models of tissue hypoxia. Reynolds, et al. and Bennett-Guerrero, et al. were prompted by observational studies showing an association between worse clinical outcomes in critically ill medical and surgical patients who had received RBC transfusions or transfusions of RBC units with prolonged storage times.3 They sought to determine whether collecti on and storage of blood under standard blood bank conditions resulted in changes in the content of RBC NO equivalents and hypoxic vasodilatory function, which, in turn, might explain a loss of efficacy for RBC transfusions in patients at high risk for ischemic tissue injury.

Both of these studies demonstrated rapid depletion of RBC SNO-Hb and membrane SNO concentrations that began as early as three hours after blood draw (prior to leukofiltration and processing) and persisted for six weeks. In concert with SNO-Hb depletion, stored RBCs exhibited significantly impaired vasodilatory activity in hypoxic rabbit aortic ring bioassays. The mechanism for rapid SNO-Hb loss was not defined nor was a direct correlation between SNO-Hb depletion and other biochemical RBC storage lesions identified. Bennett-Guerrero, et al. did observe a slow decline in RBC deformability that became more marked at two to six weeks of storage, possibly relevant to reports of adverse outcomes after transfusion with older banked blood.3 Reynolds, et al. showed that RBCs stored for up to six weeks could be renitrosylated by exposure to aqueous NO and adjustment of pH, and this reconstituted the SNO-Hb concentrations and hypoxic vasodilatory functions in organ chamber and live-animal canine coronary artery models.

In Brief

These observations identify an important storage lesion in banked blood that profoundly affects the ability of RBCs to function as an O2-responsive vasoregulator. The reason for rapid SNO-Hb loss ex vivois not defined nor is it known whether SNO-Hb levels and functional activity can be recovered in RBCs after transfusion. For patients with critical illness and tissue hypoxia, transfusion of SNO-Hb depleted RBCs could theoretically displace enough native RBCs to impair normal vasodilatory function and augment ischemic injury, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality. Altered RBC SNO-Hb levels have been implicated in the vasculopathic processes associated with sickle cell disease, diabetes, and pulmonary hypertension. Transfusion practices for these patients, and perhaps others with chronic cardiac, pulmonary, and vascular diseases, should be re-evaluated in light of these findings. The observation that SNO-Hb levels and experimental vasodilatory activity could be reconstituted by renitrosylation raises the intriguing notion that blood banks in the future might be able to provide "recharged" RBCs for anemic critically ill patients, for red cell exchange to treat severe sickle cell crisis, and for other transfusion indications in selected high-risk individuals.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Linenberger indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.