Dr. Schwartz is a Deputy Editor of the New England Journal of Medicine.

William Dameshek (1900-1969) was the preeminent American clinical hematologist of his time. A polymath, his interests ranged from diseases of the blood to pre-Columbian statuettes. He was a lead investigator in the first-known multi-institutional trial of chemotherapy (nitrogen mustard for Hodgkin lymphoma). Dr. Dameshek pioneered in the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia with corticosteroids, introduced antimetabolite therapy for autoimmune diseases, developed the concepts of the myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative disorders, and proposed that CLL is the result of a gradual accumulation of lymphocytes. He was the founder ofBlood, an architect of the American Society of Hematology, and an organizer of the International Society of Hematology (ISH).

Dr. Dameshek was named Ze'ev at his birth in Voronezh, Russia, and, at the age of three, was brought to the United States by his parents, who settled in Medford, MA, and renamed him William. An exceptional student at Boston's English High School (the oldest public high school in America), he went to Harvard College, and in 1923 he graduated from Harvard Medical School and married Rose (Ruddy) Thurman.

During his internship at Boston City Hospital, he worked with Dr. Ralph Larrabee, a Tufts professor who had established a "Blood Laboratory" in the basement of the hospital. Dr. Dameshek's first research paper was titled "The reticulated blood cells — their clinical significance." Dr. Dameshek was also drawn to hematology by George Minot, director of the Thorndike Memorial Laboratory of the hospital, who in 1925 was treating pernicious anemia — then a fatal disease — with raw liver. In 1939, Dr. Dameshek established the Blood Research Laboratory at what was to become the New England Medical Center (now Tufts Medical Center). There he did the work that brought him international recognition.

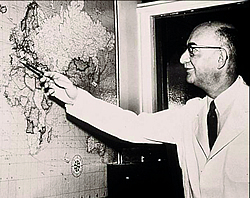

From left to right: Drs. Ray Owen, Theodore Spaet, Ernest Beutler, William Dameshek, and Leon Jacobson converse during a symposium sponsored by Dr. Beutler at City of Hope in 1961.

From left to right: Drs. Ray Owen, Theodore Spaet, Ernest Beutler, William Dameshek, and Leon Jacobson converse during a symposium sponsored by Dr. Beutler at City of Hope in 1961.

Dr. Dameshek was a gifted teacher. He ran the most popular course (hematology) for medical students at Tufts University School of Medicine; his Saturday morning hematology Grand Rounds at the New England Medical Center were legendary. He trained more than 100 hematologists from 20 countries. Former trainees still remember walking rounds with Dr. Dameshek — 20 fellows and students trailing the master through the hospital. Dr. Dameshek knew better than any of us how to take a history, perform a physical examination, and interpret a blood smear. In the hallway, after leaving the patient, he would quiz, cajole, and tease the fellows but never embarrass, and never parade his knowledge. He could effortlessly admit, "I don't know." ("We'll vote," he'd say about a difficult problem or decision.) Above all, he was deeply empathetic with patients for whom there were few effective treatments. He never denied them hope, never seemed rushed, never failed to touch them.

Dr. Dameshek was not a laboratory investigator. He was a busy clinician who took the time to think deeply about his patients and their diseases. He was tireless. He wrote five books and more than 350 articles and editorials. He would arrive in his office on Monday morning with a bundle of lined white paper on which he had, over the weekend, written in characteristic green ink his latest thoughts on PNH, CLL, or myelodysplasia. On some Mondays, he would arrive bursting with a wonderful new idea about the origin of lymphomas, or the relation between PNH and aplastic anemia, or why immune thrombocytopenia develops in systemic lupus erythematosus. Soon after we (puppies) had yelped our objections to the latest idea, it would appear as an editorial in Blood.

Dr. Dameshek demanded from us fellows his own level of enthusiasm, commitment, and effort. It wasn't easy to emulate the boss. On Friday, October 4, 1957, the day the Sputnik satellite went into orbit, we received a memorable lecture on our deficiencies. Later, he apologized even though we knew that he meant every word.

Patients came from everywhere to seek Dr. Dameshek's counsel. Luminaries arrived regularly. He collected art, lived in a beautiful house in Brookline, loved music (Serge Koussevitzky was his patient), and entertained grandly thanks to Ruddy. Dressed by Louis, Boston's high-end haberdasher, Dr. Dameshek cut a stylish figure. He was, from outward appearances, the antithesis of the staid, underpaid Boston academic. He would brush off petty jealousies with a shrug. His favorite response to the critics was, "Every knock is a boost."

Dr. Dameshek had an extraordinary influence on the development of hematology in America. He used his intelligence, independence, and influence in ways that benefited not only hematologists but also patients. His legacy is unique.