High-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has played a central role in multiple myeloma (MM) therapy since the approach was first introduced by McElwain and colleagues in 1983.1 ASCT was initially most often utilized in the management of relapsed and refractory disease, wherein it provided a means to overcome drug resistance through dose intensification. Although brief, significant responses were observed in this setting. ASCT was subsequently evaluated in newly diagnosed MM patients following induction therapy. In a pivotal trial comparing standard-dose chemotherapy to standard-dose therapy followed by ASCT, the incorporation of ASCT improved overall response, complete response, event-free survival, and overall survival.2 Subsequent clinical trials comparing conventional therapy to ASCT yielded conflicting results, as some demonstrated improvement in event-free and overall survival associated with ASCT patients, while others did not. Comparison of single versus tandem ASCT showed benefit of a second transplant limited to those who did not achieve at least a very good partial response after the first and to patients with otherwise favorable disease characteristics, such as normal cytogenetics and low β2-microglobulin.3 With respect to timing, early ASCT following induction therapy is associated with improvement in event-free survival relative to delayed transplant at time of relapse, but not with improvement in overall survival.4

ASCT has traditionally been undertaken with caution in the context of high-risk disease as defined by cytogenetic abnormalities such as translocation (t)(4;14), due to shortened time-to-progression and overall survival post-transplant in this population. Outcomes with ASCT are best among individuals who achieve maximal reduction in tumor burden, and multiple studies have shown that complete response following ASCT is associated with prolonged event-free survival and overall survival. It would thus appear that the benefit of ASCT in MM derives from its ability to induce deeper responses through dose intensification and thereby suppress the tumor clone for an extended period.

The Impact of Thalidomide, Bortezomib, and Lenalidomide on Myeloma Therapy

Although ASCT remains a critical treatment option for appropriately selected MM patients, the introduction of thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide in the past decade has dramatically altered the overall therapeutic management of MM. Clinical trials comparing the historical standard of care for upfront therapy in transplant-ineligible patients— melphalan and prednisone (MP) — to MP in combination with either thalidomide5 or bortezomib6 showed superior overall and complete response rates, as well as improved duration of response and overall survival. Likewise, preliminary analysis of a phase III study comparing MP, MP plus lenalidomide, and MP plus lenalidomide followed by lenalidomide maintenance demonstrated substantial improvement in rates of overall and complete response as well as a significant improvement in progression-free survival in the regimen that included lenalidomide maintenance.7

Thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide also figure prominently in the treatment of newly diagnosed, transplant- eligible MM patients. Whereas the combination of vincristine, adriamycin, and dexamethasone formerly represented standard induction therapy for such patients, the regimen has been supplanted on the basis of data from randomized trials by thalidomide plus dexamethasone and by bortezomib plus dexamethasone. Specifically, the majority of patients receiving these regimens achieve at least a very good partial response after induction and a single ASCT, so that fewer patients are candidates to benefit from a second transplant. Lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone is also well tolerated and active as induction therapy in transplant-eligible patients.8 Bortezomib, lenalidomide, and/or their combination are particularly attractive for patients with high-risk disease based on staging criteria and cytogenetic abnormalities such as t(4;14) and del(13), as several studies indicate that they may overcome the poor prognosis associated with these genetic findings in relapsed disease.

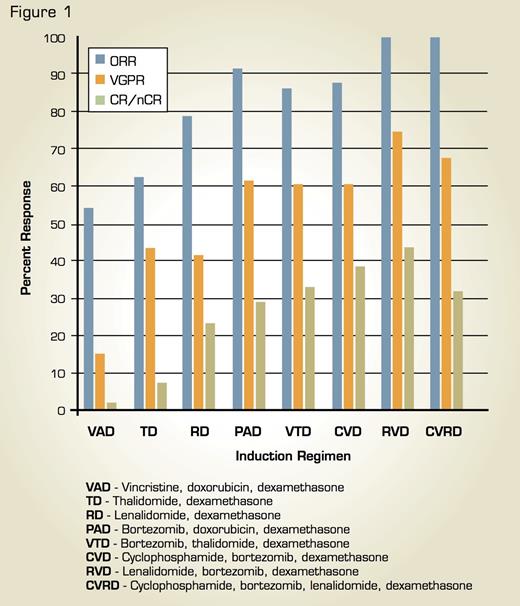

Comparison of Response Rates (Overall, Very Good Partial, and Complete/Near Complete Response) Associated With Combination Regimens in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. This research was originally published in Blood and adapted. Stewart AK, Richardson PG, San-Miguel JF. Blood. 2009;114:5436-43.

Comparison of Response Rates (Overall, Very Good Partial, and Complete/Near Complete Response) Associated With Combination Regimens in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. This research was originally published in Blood and adapted. Stewart AK, Richardson PG, San-Miguel JF. Blood. 2009;114:5436-43.

The application of thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide in MM therapy has been refined in recent years through a series of important clinical investigations. Combinations of these agents, such as bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone9 and lenalidomide, bortezomib, dexamethasone,10 are being evaluated in newly diagnosed MM and have proven to be very effective, yielding complete response rates approximating those previously achieved with highdose therapy and ASCT. In addition, schedule modifications have been introduced with the aim of minimizing toxicity while preserving the activity of chemotherapeutic regimens. Finally, building on previous studies of thalidomide maintenance therapy following ASCT, ongoing clinical trials are evaluating lenalidomide and bortezomib consolidation and maintenance following ASCT, and preliminary results suggest that increased extent of response and prolonged progression-free survival can be achieved with these agents, both as monotherapy and in combination. Figure 1 shows response rates associated with various combination regimens.

Reevaluating Stem Cell Transplantation in the New Era of Myeloma Therapy

In light of the fact that new approaches to MM induction now produce a level of response previously seen only with the incorporation of ASCT, it is critical for ASCT to be reevaluated in the context of new induction and maintenance strategies. Questions of significant interest and importance in the field include: Can highly active induction regimens followed by maintenance therapy replace upfront ASCT for patients who have been traditionally managed utilizing transplant? Conversely, will such active induction regimens followed by ASCT, and thereafter by maintenance, extend suppression of the myeloma clone beyond what has been previously achieved, with resulting prolongation of progression-free and overall survival? In addition, what is the optimal sequence of new induction regimens and ASCT; should ASCT be performed immediately following induction therapy or delayed until time of relapse?

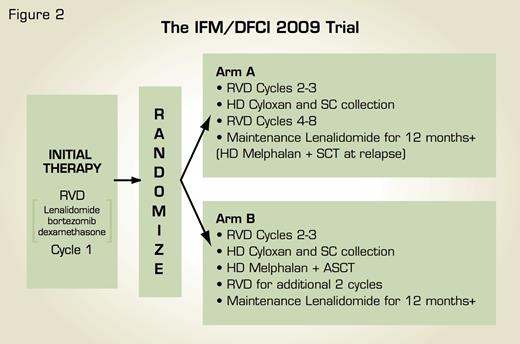

Schema for International, Randomized, Phase III Clinical Trial of RVD Induction/Consolidation and Lenalidomide Maintenance With Early Versus Delayed ASCT in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Figure courtesy of Dr. Paul Richardson.

Schema for International, Randomized, Phase III Clinical Trial of RVD Induction/Consolidation and Lenalidomide Maintenance With Early Versus Delayed ASCT in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Figure courtesy of Dr. Paul Richardson.

A randomized, international clinical trial developed by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and a consortium of U.S. transplant centers working in partnership with the Inter-Groupe Francophone du Myelome (IFM) has been designed to definitively address these issues (Figure 2). After receiving one cycle of induction with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, previously untreated MM patients will be randomized to receive either: a) further induction with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone followed by stem cell collection and ASCT, or b) further induction and stem cell collection but no ASCT until time of relapse. Patients in both treatment groups will receive consolidation with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone and then lenalidomide maintenance for at least 12 months. It is anticipated that results of this clinical trial will, together with other ongoing studies, guide optimal timing and sequence of ASCT in the rapidly evolving field of MM therapy, as well as provide insight on key surrogates and prognostic features, such as cytogenetics and gene expression profiling. MM remains a formidable adversary and must be countered with all available, active treatment modalities in the most informed, coordinated manner possible to further improve patient outcome, with the integration of novel therapies and ASCT offering a paradigm for just such an approach.

References

Competing Interests

Drs. Richardson, Munshi, and Anderson are advisory board members for Celgene and Millennium. Dr. Munshi also consults for Celgene and Millennium.